When I carried out the 1984-1985 survey of Montana as part of the state historic preservation planning process, one resource was at the forefront of my mind–railroad passenger stations. Not only had recent scholarship by John Hudson and John Stilgoe brought new interest to the topic, there had been the recent bankruptcy of the Milwaukee Road, and the end of passenger service in large parts of the state, except along the Hi-Line of the old Great Northern Railway (where Amtrak still runs today.)

The mid-20th century standardized design for Great Northern stations at Chester on US 2.

Some of the passenger stations in the major cities had already been converted into new uses, such as restaurants, offices, and various downtown commercial uses. The lovely turn of the twentieth century stations for the Great Northern (left) and the Milwaukee Road (right) in Great Falls showed how the location of the buildings, plus their

architectural quality and the amount of available space made them perfect candidates for adaptive reuse. While the tenants have changed over the past 30 plus years, both buildings still serve as heritage anchors for the city. While success marked early adaptive reuse projects in Great Falls and Missoula, for instance, it was slow to come to Montana’s largest city–the neoclassical styled Northern Pacific depot was abandoned and

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

In the 1984-1985 I documented hundreds of railroad depots across Big Sky Country. From 2012-2015 I noted how many had disappeared–an opportunity to preserve heritage and put a well-located substantial building for the building back to work had been wasted. But I also came away with a deep appreciation of just how many types of new lives train stations could have.

Turning iconic buildings into community museums is a time-honored tradition, as you can find at the magnificent Northern Pacific station at Livingston, shown above. A handful of Montana communities have followed that tradition–I am especially glad that people in Harlowton and Wheatland County banded together to preserve the

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

But there are so many other uses–as they know in Lewistown. Already in the mid-1980s investors in Lewistown had turned the old Milwaukee Road station, shown above, into a hotel and conference center, the Yogo Inn. When I visited Lewistown in 2013 the Yogo was undergoing a facelift after 30 years as a commercial business. The town’s other

historic depot, a substantial brick building (above) from the Great Northern Railway, was a gas station, convenience mart, office building, and store, all in one.

Deer Lodge is blessed with both of its historic depots. The Milwaukee Road depot has become a church while the Northern Pacific depot became the Powell County Senior Citizens Center. Indeed, converting such a community landmark into a community center is popular in other Montana towns, such as the National Register-listed passenger station shown below in Kevin, Toole County, near the border with Canada.

One of the most encouraging trends of this century is how many families have turned depots into their homes–you can’t beat the location and the long, horizontal nature of the often-found combination depot (passenger station and luggage warehouse in same building) means that these dwellings have much in common with the later Ranch-style houses of the 1950s and 1960s.

A former Great Northern depot in Windham.

A Milwaukee Road depot turned into a home in Rosebud County.

But in my work from 2012-15 I found more and more examples of how local entrepreneurs have turned these historic buildings into businesses–from a very simple, direct conversion from depot to warehouse in Grassrange to the use of the Milwaukee Road depot in Roundup as the local electric company office.

As these last examples attest–old buildings can still serve communities, economically and gracefully. Not all historic preservation means the creation of a museum–that is the best course in only a few cases. But well-built and maintained historic buildings can be almost anything else–the enduring lesson of adaptive reuse

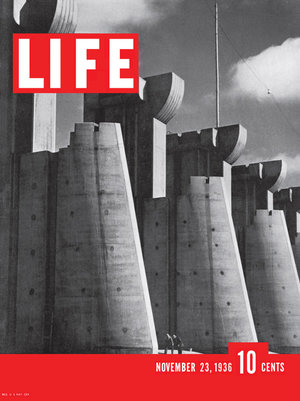

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

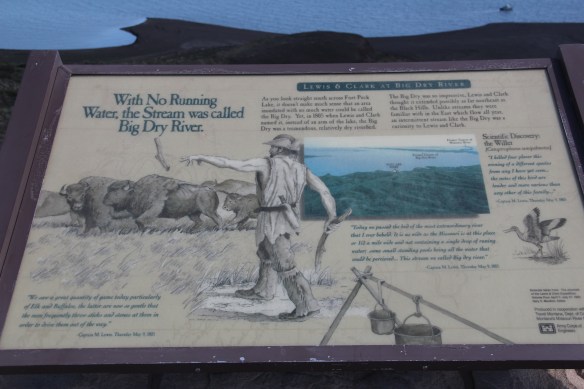

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now. New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do.

New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do. You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89.

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89. Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta  won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined?

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined? Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

I love Montana town signs, and Troy, deep in the state’s logging country, has one of the best. The sign lures to a city park nestled along the Kootenai River. The focus point is a

I love Montana town signs, and Troy, deep in the state’s logging country, has one of the best. The sign lures to a city park nestled along the Kootenai River. The focus point is a

the Great Northern’s main line, and I documented the few historic buildings left facing the railroad tracks today. The Home Bar (c. 1914) and the Club Bar were institutions then, and remain so today. The Kootenai State Bank building still stands but has experienced a major change to its facade–made better in part by the American flag painted over some of the frame addition.

the Great Northern’s main line, and I documented the few historic buildings left facing the railroad tracks today. The Home Bar (c. 1914) and the Club Bar were institutions then, and remain so today. The Kootenai State Bank building still stands but has experienced a major change to its facade–made better in part by the American flag painted over some of the frame addition. The Troy Jail, above, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and it remains the only building so listed in the town today. D.E. Crissey, a local contractor, built it out of concrete in 1924 during Troy’s boom from 1916 to 1926 when its population jumped from 300 to 1300. The Snowstorm mine, which produced lead, zinc, and silver, started to serve the demand for raw materials during World War I. The mine soon turned what had been a small railroad town into a mining camp best known for its brothels and bars. Then in the early 1920s the Great Northern decided to build a division point here, further booming the town. The Sandpoint Pole and Lumber Company began its logging business in 1923, and Troy suddenly was the largest town in the county

The Troy Jail, above, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and it remains the only building so listed in the town today. D.E. Crissey, a local contractor, built it out of concrete in 1924 during Troy’s boom from 1916 to 1926 when its population jumped from 300 to 1300. The Snowstorm mine, which produced lead, zinc, and silver, started to serve the demand for raw materials during World War I. The mine soon turned what had been a small railroad town into a mining camp best known for its brothels and bars. Then in the early 1920s the Great Northern decided to build a division point here, further booming the town. The Sandpoint Pole and Lumber Company began its logging business in 1923, and Troy suddenly was the largest town in the county

Libby is the seat of Lincoln County, a typical railroad town along the historic Great Northern Railway corridor. The image above is from the town’s railroad depot, the symbolic beginning of town, from which runs a long main street of businesses, reflecting the T-plan town design, where the long railroad corridor defines the top of the T and the main street forms the stem of the T.

Libby is the seat of Lincoln County, a typical railroad town along the historic Great Northern Railway corridor. The image above is from the town’s railroad depot, the symbolic beginning of town, from which runs a long main street of businesses, reflecting the T-plan town design, where the long railroad corridor defines the top of the T and the main street forms the stem of the T.

courthouse received a totally new front, in a contemporary style, in the 1970s as the town and county expanded in the wake of the federal spending in constructing Libby Dam. The rectangular blockiness, flat roof, and band of windows set within a symmetrical facade makes the courthouse one of the state’s best designs for a rural public building in the late 20th century.

courthouse received a totally new front, in a contemporary style, in the 1970s as the town and county expanded in the wake of the federal spending in constructing Libby Dam. The rectangular blockiness, flat roof, and band of windows set within a symmetrical facade makes the courthouse one of the state’s best designs for a rural public building in the late 20th century. I liked all of those things about Libby in 1984. Imagine my shock and disappointment to learn, as everyone else did, that Libby was one of the poisoned places in the west. In 1919, vermiculite, a natural material that contains asbestos, had been discovered outside of town, and the mines were still operating, producing 80 percent of the vermiculite in the world, under the control of the W.R. Grace company. Residue from the mines had been used in local yards and buildings for decades, a fact that was not known when I visited the town for the state historic preservation plan. When the discovery of the danger became public, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency entered into the fray in 1999, it was already too late for many residents. A federal Superfund project began, and did not conclude its work until 2015, spending some $425 million. Then in 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency announced a public health emergency, spending another $130 million to help residents and to leave a new health infrastructure in place. In a generation, Libby had been turned inside out. EPA announced in 2016 that the cleanup would continue to 2018, and that the project was the longest in the agency’s history.

I liked all of those things about Libby in 1984. Imagine my shock and disappointment to learn, as everyone else did, that Libby was one of the poisoned places in the west. In 1919, vermiculite, a natural material that contains asbestos, had been discovered outside of town, and the mines were still operating, producing 80 percent of the vermiculite in the world, under the control of the W.R. Grace company. Residue from the mines had been used in local yards and buildings for decades, a fact that was not known when I visited the town for the state historic preservation plan. When the discovery of the danger became public, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency entered into the fray in 1999, it was already too late for many residents. A federal Superfund project began, and did not conclude its work until 2015, spending some $425 million. Then in 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency announced a public health emergency, spending another $130 million to help residents and to leave a new health infrastructure in place. In a generation, Libby had been turned inside out. EPA announced in 2016 that the cleanup would continue to 2018, and that the project was the longest in the agency’s history.

Despite the disaster, I saw many signs that Libby residents were determined to remain and rebuild their community. One of the most powerful examples is the conversion of one of the town’s historic schools into a new community arts center as well as school administration offices.

Despite the disaster, I saw many signs that Libby residents were determined to remain and rebuild their community. One of the most powerful examples is the conversion of one of the town’s historic schools into a new community arts center as well as school administration offices.

The asbestos crisis was a terrible disaster for Libby–yet residents refused to let it define their future. There are past accomplishments to acknowledge, an active railroad depot to cherish, a beautiful river and lake, the mountains all around, as celebrated in this public art mural on a downtown building. This place is here to stay, and the historic built environment is a large part of it.

The asbestos crisis was a terrible disaster for Libby–yet residents refused to let it define their future. There are past accomplishments to acknowledge, an active railroad depot to cherish, a beautiful river and lake, the mountains all around, as celebrated in this public art mural on a downtown building. This place is here to stay, and the historic built environment is a large part of it.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core. The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century. Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks.

Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks. But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

Missoula County has grown, a lot, since my state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985, especially in the county seat of Missoula and surrounding suburbs. Yet Missoula County still has several spectacular rural drives, like Montana Highway 83 above at Condon, along with distinctive country towns. This post will share some of my favorites.

Missoula County has grown, a lot, since my state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985, especially in the county seat of Missoula and surrounding suburbs. Yet Missoula County still has several spectacular rural drives, like Montana Highway 83 above at Condon, along with distinctive country towns. This post will share some of my favorites.

The Condon Community Center and adjacent Swan Valley Community Library serve as additional hubs for those living along the lakes and mountains of northeast Missoula County. Both buildings are excellent examples of mid-20th century Rustic style–a look that, in different variations, dominates the Highway 35 corridor.

The Condon Community Center and adjacent Swan Valley Community Library serve as additional hubs for those living along the lakes and mountains of northeast Missoula County. Both buildings are excellent examples of mid-20th century Rustic style–a look that, in different variations, dominates the Highway 35 corridor.

Condon is also the base for the Condon Work Center, home to the Great Northern Fire Crew, of the Flathead National Forest. Here you can take a mile-long Swan Ecosystem Trail and learn of the diversity of life in this national forest region.

Condon is also the base for the Condon Work Center, home to the Great Northern Fire Crew, of the Flathead National Forest. Here you can take a mile-long Swan Ecosystem Trail and learn of the diversity of life in this national forest region. South of Condon on Montana Highway 83 is Seeley Lake–a place that certainly has boomed in the last 30 years–witness the improved highway, new businesses, and population that has increased over 60 percent since my last visit in 1992. Yet it still had places rooted in the community’s earlier history such as the Sullivan Memorial Community Hall–a good example of mid-20th century Rustic style.

South of Condon on Montana Highway 83 is Seeley Lake–a place that certainly has boomed in the last 30 years–witness the improved highway, new businesses, and population that has increased over 60 percent since my last visit in 1992. Yet it still had places rooted in the community’s earlier history such as the Sullivan Memorial Community Hall–a good example of mid-20th century Rustic style. And it had added one of my favorite bits of roadside architecture in this part of Montana: the Chicken Coop Restaurant as well as opening a new Seeley Lake Historical Museum and Chamber of Commerce office at a spectacular highway location just outside of town.

And it had added one of my favorite bits of roadside architecture in this part of Montana: the Chicken Coop Restaurant as well as opening a new Seeley Lake Historical Museum and Chamber of Commerce office at a spectacular highway location just outside of town.

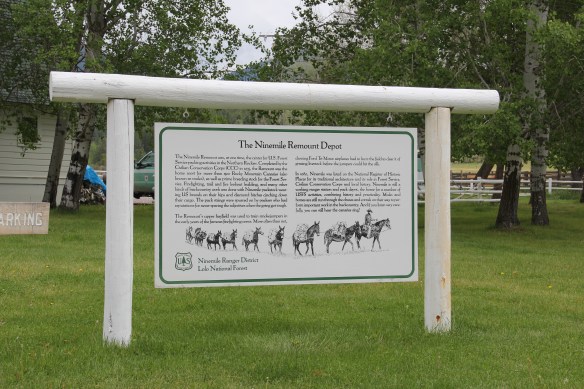

I don’t recall even thinking about the forest service facility, but here was an entire complex devoted to the forest service’s use of mules and horses before the days of the ATV that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The remount depot is an interesting

I don’t recall even thinking about the forest service facility, but here was an entire complex devoted to the forest service’s use of mules and horses before the days of the ATV that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The remount depot is an interesting

The name Frenchtown dates to 1868 and is a reference to a number of French Canadians who moved here in the early settlement period. A National Register-listed church, the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (1884) marks that first generation of settlers. Its classical-tinged cupola has long been the town’s most famous landmark.

The name Frenchtown dates to 1868 and is a reference to a number of French Canadians who moved here in the early settlement period. A National Register-listed church, the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (1884) marks that first generation of settlers. Its classical-tinged cupola has long been the town’s most famous landmark. The Milwaukee Road built through here in 1907-1908 and there remains a handful of historic business buildings from the time of the Milwaukee boom. There is one landmark

The Milwaukee Road built through here in 1907-1908 and there remains a handful of historic business buildings from the time of the Milwaukee boom. There is one landmark

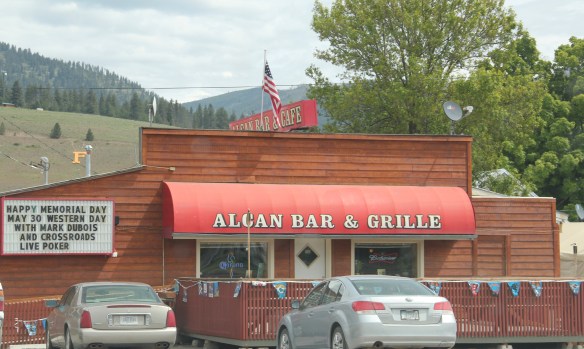

another roadside landmark–the Bucksnort Bar, just further evidence to add to the Chicken Coop and the Alcan that you won’t go hungry if you explore the small towns of Missoula County.

another roadside landmark–the Bucksnort Bar, just further evidence to add to the Chicken Coop and the Alcan that you won’t go hungry if you explore the small towns of Missoula County.

Drummond is the north entrance of the Pintler Scenic Route. The first ranchers settled here in the 1870s but a proper town, designed in symmetrical fashion facing the railroad tracks, was not established until 1883-1884 as the Northern Pacific Railroad built through here following the Clark’s Fork River to Missoula.

Drummond is the north entrance of the Pintler Scenic Route. The first ranchers settled here in the 1870s but a proper town, designed in symmetrical fashion facing the railroad tracks, was not established until 1883-1884 as the Northern Pacific Railroad built through here following the Clark’s Fork River to Missoula.

There is a faintly classically influenced two-story brick commercial block, a Masonic Lodge made of concrete block, various bars and cafes, a railroad water tank, and a slightly Art Deco movie theater, which was open in the 1980s but is now closed.

There is a faintly classically influenced two-story brick commercial block, a Masonic Lodge made of concrete block, various bars and cafes, a railroad water tank, and a slightly Art Deco movie theater, which was open in the 1980s but is now closed.

Due to the federal highway and the later Interstate I-90 exit built at Drummond, the town even has a good bit of motel roadside architecture from c. 1970 to 1990.

Due to the federal highway and the later Interstate I-90 exit built at Drummond, the town even has a good bit of motel roadside architecture from c. 1970 to 1990.

Between the Northern Pacific corridor and old U.S. 10 is the town’s most famous contemporary business, its “Used Cow” corrals, and now far away, on the other side of the

Between the Northern Pacific corridor and old U.S. 10 is the town’s most famous contemporary business, its “Used Cow” corrals, and now far away, on the other side of the tracks are rodeo grounds named in honor of Frank G. Ramberg and James A. Morse, maintained by the local American Legion chapter.

tracks are rodeo grounds named in honor of Frank G. Ramberg and James A. Morse, maintained by the local American Legion chapter.

The rodeo grounds are not the only cultural properties in Drummond. The Mullan Road monument along the old highway is the oldest landmark. The local heritage museum is at the New Chicago School (1874), an frame one-story school moved from the Flint River Valley to its location near the interstate and turned into a museum.

The rodeo grounds are not the only cultural properties in Drummond. The Mullan Road monument along the old highway is the oldest landmark. The local heritage museum is at the New Chicago School (1874), an frame one-story school moved from the Flint River Valley to its location near the interstate and turned into a museum.

Another local museum emphasizes contemporary sculpture and painting by Bill Ohrmann. A latter day “cowboy artist” Ohrmann grew up in the Flint River Valley but by the 12960s he was producing sculpture and painting on a regular basis. The museum is also a gallery and his works are for sale, although the huge sculptures might not be going anywhere.

Another local museum emphasizes contemporary sculpture and painting by Bill Ohrmann. A latter day “cowboy artist” Ohrmann grew up in the Flint River Valley but by the 12960s he was producing sculpture and painting on a regular basis. The museum is also a gallery and his works are for sale, although the huge sculptures might not be going anywhere.

contemporary styling of the Ravalli County Bank or the “new” county courthouse of 1976, a building that I totally dismissed in 1984 but now that it has reached the 40 year mark the design seems so much of its time, and a very interesting local reaction by the firm of Howland and Associates to the ne0-Colonial Revival that gripped so much of the nation during the American bicentennial.

contemporary styling of the Ravalli County Bank or the “new” county courthouse of 1976, a building that I totally dismissed in 1984 but now that it has reached the 40 year mark the design seems so much of its time, and a very interesting local reaction by the firm of Howland and Associates to the ne0-Colonial Revival that gripped so much of the nation during the American bicentennial.

Adaptive reuse had put some buildings back into use, such as the historic Creamery, once such an important link between town and ranch in the county. Other landmarks didn’t

Adaptive reuse had put some buildings back into use, such as the historic Creamery, once such an important link between town and ranch in the county. Other landmarks didn’t

Montana Highway 41 and the western side of the county is where I start, with the town of Silver Star, nestled between a spur line of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Highway 41, and Jefferson River. Gold was discovered nearby in 1866 and the town is named for a mine, but growth came more from transportation, with Silver Star serving as an early transportation stop between Virginia City and Helena in the 1870s. Today the place is best known for a privately held massive collection of mining machines, tools, and artifacts established by Lloyd Harkins, and for its rural post office that is nestled within the town’s general store.

Montana Highway 41 and the western side of the county is where I start, with the town of Silver Star, nestled between a spur line of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Highway 41, and Jefferson River. Gold was discovered nearby in 1866 and the town is named for a mine, but growth came more from transportation, with Silver Star serving as an early transportation stop between Virginia City and Helena in the 1870s. Today the place is best known for a privately held massive collection of mining machines, tools, and artifacts established by Lloyd Harkins, and for its rural post office that is nestled within the town’s general store.

valley and its irrigation systems helped to produce one of the most famous barns in the state: the Round Barn, just north of Twin Bridges. In 1882 Noah Armstrong, who had made a fortune in mining, built the barn as part of his Doncaster Stable and Stud Farm. In 1933

valley and its irrigation systems helped to produce one of the most famous barns in the state: the Round Barn, just north of Twin Bridges. In 1882 Noah Armstrong, who had made a fortune in mining, built the barn as part of his Doncaster Stable and Stud Farm. In 1933 the Bayers family acquired the barn and incorporated it into their cattle business. When I visited in 1912 the barn was still an agricultural structure, with its wedding cake shape casting a distinct profile on the landscape. In 2015, the barn was restored to a new use: as a wedding and event reception space.

the Bayers family acquired the barn and incorporated it into their cattle business. When I visited in 1912 the barn was still an agricultural structure, with its wedding cake shape casting a distinct profile on the landscape. In 2015, the barn was restored to a new use: as a wedding and event reception space.

The result is spectacular, and with their restoration in the last 30 years, the buildings are not just landmarks but busy throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

The result is spectacular, and with their restoration in the last 30 years, the buildings are not just landmarks but busy throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

The Old Hotel, a brick two-story gable-front building, also marks the town’s ascent during the early 20th century when the town achieved its highest population, about 750 in 1920. Today about half of that number call Twin Bridges home.

The Old Hotel, a brick two-story gable-front building, also marks the town’s ascent during the early 20th century when the town achieved its highest population, about 750 in 1920. Today about half of that number call Twin Bridges home. My personal favorite, and a frequent stop during the 1980s, is the Blue Anchor Bar, nestled on the first floor, with an Art Deco style redesign, in a two-story commercial block.

My personal favorite, and a frequent stop during the 1980s, is the Blue Anchor Bar, nestled on the first floor, with an Art Deco style redesign, in a two-story commercial block. Twin Bridges is a very important river junction, thus the name, where the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Ruby rivers all meet to form the Jefferson River. A public park near the confluence just south of the Montana 41/287 helps to tell that story. Nearby is the Twin Bridges School and its amazing modernist styled gymnasium.

Twin Bridges is a very important river junction, thus the name, where the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Ruby rivers all meet to form the Jefferson River. A public park near the confluence just south of the Montana 41/287 helps to tell that story. Nearby is the Twin Bridges School and its amazing modernist styled gymnasium.