Roundup, the seat of Musselshell County, has long been one of my favorite Montana county seats. The old 19th century cattle trails are one important defining feature of the eastern Montana landscape; another are the railroad lines that crossed the region. Here at Roundup, a north-south cattle trail crosses the east-west railroad line, creating a town environment rich in history.

Locals gathered at the town’s several good historic bars–the Arcade being my favorite–are rich in tales of the chaos and fun of early September 1989 when cowboys and pretend cowboys gathered in mass to recreate the “Great Montana Cattle Drive.” A monument to that crazy day stands next to Roundup’s outstanding New Deal-era courthouse. Another sign to that time is much more lonely, on Main Street, the old historic route of the trail (now part of U.S. Highway 87). Are you supposed to stand there for a selfie if you rode in ’89?

There are so many Stockman Bars in Montana. The one is Roundup has these two great Art Deco-like windows.

The coming of the Milwaukee Road in 1906-1907 created a new look to Roundup. Like many Milwaukee towns in Montana, it has a T-plan, with the route of the tracks (the rails

I was glad to see this light industrial adaptive reuse of the Milwaukee depot–it was abandoned in 1985 and could have been demolished.

have been removed since c. 1985) and the location of the depot forming the top part of the T while the stem of the T is the route of U. S. 87 as it stretches to the north.

Earlier posts have discussed the town’s contribution to Montana modernism, St. Benedict’s Catholic Church, and the superb Musselshell County Fairgrounds, one of my favorite in the state (and a public property eligible for the National Register IMHO). Roundup has two National Register properties–its two historic schools. The St. Benedict Catholic School (c. 1920), designed by Roundup’s own John Grant, is now the Musselshell Valley Museum.

The town’s historic public school, but in two major sections in 1911 and 1913, was designed by the Billings architectural firm of Link and Haire. It is an impressive landmark, built from stone taken from the bluffs of the Musselshell River Valley, and one maintained with pride by the community.

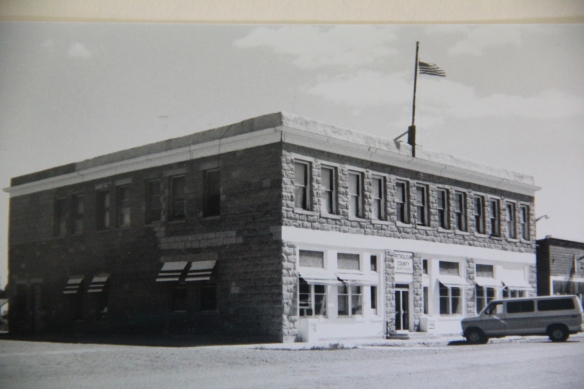

Many historic buildings from the early 20th century line Main Street–naturally many one-story buildings but also commercial blocks of style and substance. There is also a lot of homes that would contribute to a residential historic district. Roundup has lost population like almost all eastern Montana towns since 1980 but not by such a severe amount–just over 200 in the last 30 years. Thus, the town’s historic buildings remain in use and in fairly good condition.

The historic schools in Roundup have been a great start for heritage efforts in Roundup but this quick overview shows that more can be done, to document and preserve this pivotal place in the Musselshell Valley.