Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

A photo of the asylum from 2007

years later. The architect was John C. Paulsen, who then served as the State Architect. The building represents an early effort by the state to provide for its citizens, and the presence of the institution in Boulder shaped that town’s history for the next 120 years.

Boulder is a place of impressive public buildings. The Jefferson County Courthouse (1888-89) is another piece of Victorian architecture, in the Dichardsonian Romanesque style, again by John K. Paulsen. It was listed in the National Register in 1980.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Indeed the importance of schools to not only the state’s history of education but the mere survival of communities has been pinpointed by various state preservation groups and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Jefferson County still has many significant surviving school buildings from the early 20th century, none of which have been listed yet in the National Register.

Carter School, 1916, Montana City

Clancy School, now the Jefferson County Museum

Basin school, still in use

Caldwell school, one of the few buildings left in this old railroad town

Whitehall still has its impressive Gothic style gymnasium from the 1920s while the school itself shows how this part of the county has gained in population since 1985.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Irrigation and sugar beet cultivation are key 20th century agricultural themes, typically associated with eastern and central Montana. Jefferson County tells that story too, in a different way, at Whitehall. The irrigation ditches are everywhere and the tall concrete stack of the sugar refinery plant still looms over the town.

In 1917 Amalgamated Sugar Company, based in Utah, formed the Jefferson Valley Sugar Company and began to construct but did not finish a refinery at Whitehall. The venture did not begin well, and the works were later sold to the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company in 1920, which never finished the plant but left the stack standing. Nearby is Sugar Beet

Row, where hipped roof duplex residences typical of c. 1920 company towns are still lined up, and in use, although their exteriors have changed over the decades.

Through many posts in this blog, I have identified those informal yet very important community centers found in urban neighborhoods and rural outposts across the state–bars and taverns. Jefferson County has plenty of famous classic watering holes, such as Ting’s Bar in Jefferson City, the Windsor Bar in Boulder, or the Two Bit Bar in Whitehall, not forgetting Roper Lanes and Lounge in Whitehall.

Speaking of recreation, Jefferson County also has one of my favorite hot springs in all of the west, the Boulder Hot Springs along Montana Highway 69. Here is a classic oasis of the early 20th century, complete in Spanish Revival style, and listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Its rough worn exterior only hints at the marvel of its pool and experience of this place.

Mining always has been part of Jefferson County’s livelihood with still active mines near Whitehall and at Wickes. The county also has significant early remnants of the state’s

The coke ovens above are from Wickes (L) and Alhambra (R) while the image directly above is of 21st century mining continuing at Wickes.

mining era, with still extant (but still threatened as well) charcoal kilns at Wickes (1881) and at Alhambra. Naturally with the mining came railroads early to Jefferson County. As you travel Interstate I-15 between Butte and Helena, you are generally following the route of the Montana Central, which connected the mines in Butte to the smelter in Great Falls, and a part of the abandoned roadbed can still be followed.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Corbin concentrator site, 1984

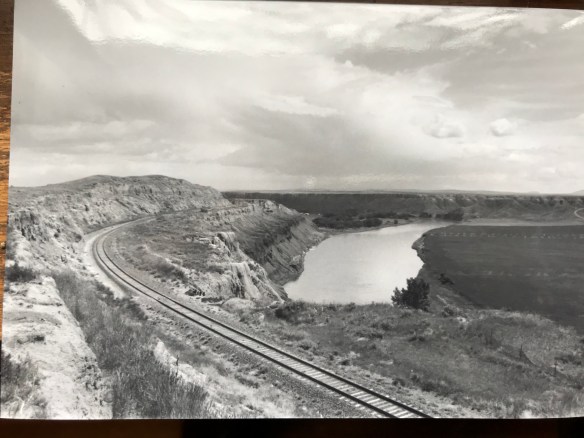

The Northern Pacific Railroad and the Milwaukee Road were both active in the southern end of the county. Along one stretch of the Jefferson River, which is followed by Montana Highway 2 (old U.S. Highway 10), you are actually traversing an ancient transportation route, created by the river, the railroads, and the federal highway. The Northern Pacific tracks are immediately next to the highway between the road and the Jefferson River; the Milwaukee corridor is on the opposite side of the river.

The most famous remnant of Montana’s mining era is the ghost town at Elkhorn. Of course the phrase ghost town is a brand name, not reality. People still live in Elkhorn–indeed more now than when I last visited 25 years ago. Another change is that the two primary landmarks of the town, Fraternity Hall and Gilliam Hall, have become a pocket state park, and are in better preservation shape than in the past.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

The adjacent Gillian Hall is also an important building, not as architecturally ornate as Fraternity Hall, but typical of mining town entertainment houses with bars and food on the first floor, and a dance hall on the second floor.

While the state park properties dominate what remains at Elkhorn, it is the general unplanned, ramshackle appearance and arrangement of the town that conveys a bit of what these bustling places were like over 130 years ago–residences and businesses alike thrown up quickly because everyone wanted to make their pile and then move on.

Elkhorn is not the only place of compelling vernacular architecture. Visible along Interstate I-15 is a remarkable set of log ranch buildings near Elk Park, once a major dairy center serving Butte during the 1st half of the twentieth century. John and Rudy Parini constructed the gambrel-roof log barn, to expand production available from an earlier log barn by their father, in c. 1929. The Parini ranch ever since has been a landmark for travelers between Butte and Helena.

Nearby is another frame dairy barn from the 1920s, constructed and operated by brothers George and William Francine. The barns are powerful artifacts of the interplay between urban development and agricultural innovation in Jefferson County in the 20th century.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte. The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

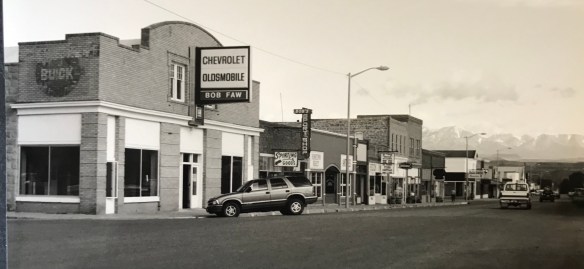

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

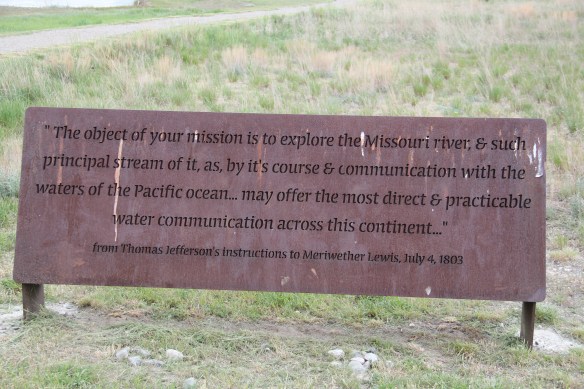

West of Whitehall is another 20th century roadside attraction, Lewis and Clark Caverns, a property with one of the most interesting conservation histories in the nation. It began as a privately developed site and then between 1908 and 1911 it became the Lewis and Clark Cavern National Monument during the administration of President William Howard Taft. Federal authorities believed that the caverns had a direct connection to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Corps of Discovery camped nearby on July 31, 1805, but had no direct association with the caverns. A portion of their route is within the park’s boundaries.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

Faith, and the persistence of early churches across rural Montana, is perhaps the most appropriate last theme to explore in Jefferson County. St. John the Evangelist (1880-1881) dominates the landscape of the Boulder Valley, along Montana Highway 69, like few other buildings. This straightforward statement of faith in a frame Gothic styled building, complete with a historic cemetery at the back, is a reminder of the early Catholic settlers of the valley, and how diversity is yet another reality of the Montana experience.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country. I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century. Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered. The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950. Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural

Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City.

statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City. Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive.

at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive. Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor

Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed.

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed. Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

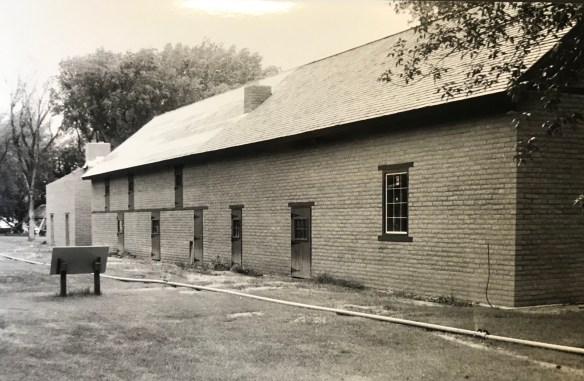

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west. The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road. The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

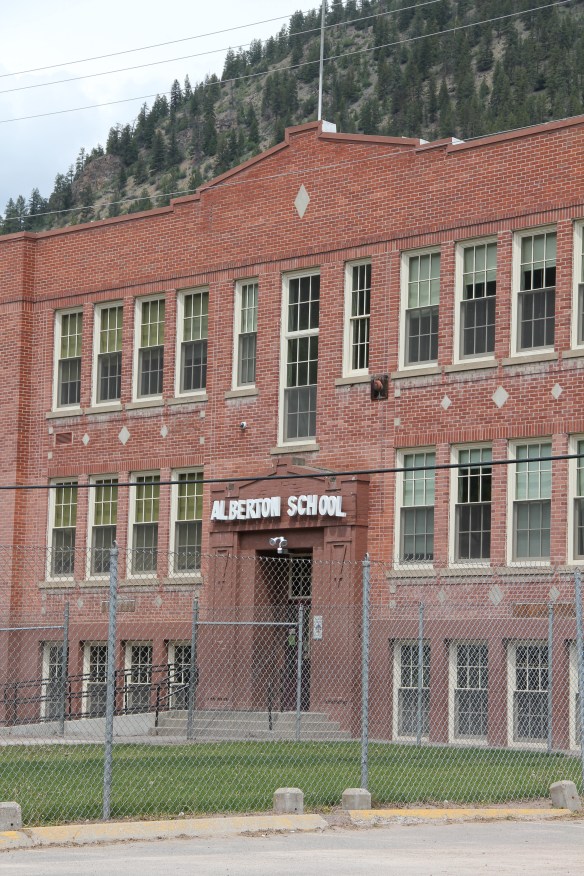

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work.

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism.

I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism. The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

Drummond is the north entrance of the Pintler Scenic Route. The first ranchers settled here in the 1870s but a proper town, designed in symmetrical fashion facing the railroad tracks, was not established until 1883-1884 as the Northern Pacific Railroad built through here following the Clark’s Fork River to Missoula.

Drummond is the north entrance of the Pintler Scenic Route. The first ranchers settled here in the 1870s but a proper town, designed in symmetrical fashion facing the railroad tracks, was not established until 1883-1884 as the Northern Pacific Railroad built through here following the Clark’s Fork River to Missoula.

There is a faintly classically influenced two-story brick commercial block, a Masonic Lodge made of concrete block, various bars and cafes, a railroad water tank, and a slightly Art Deco movie theater, which was open in the 1980s but is now closed.

There is a faintly classically influenced two-story brick commercial block, a Masonic Lodge made of concrete block, various bars and cafes, a railroad water tank, and a slightly Art Deco movie theater, which was open in the 1980s but is now closed.

Due to the federal highway and the later Interstate I-90 exit built at Drummond, the town even has a good bit of motel roadside architecture from c. 1970 to 1990.

Due to the federal highway and the later Interstate I-90 exit built at Drummond, the town even has a good bit of motel roadside architecture from c. 1970 to 1990.

Between the Northern Pacific corridor and old U.S. 10 is the town’s most famous contemporary business, its “Used Cow” corrals, and now far away, on the other side of the

Between the Northern Pacific corridor and old U.S. 10 is the town’s most famous contemporary business, its “Used Cow” corrals, and now far away, on the other side of the tracks are rodeo grounds named in honor of Frank G. Ramberg and James A. Morse, maintained by the local American Legion chapter.

tracks are rodeo grounds named in honor of Frank G. Ramberg and James A. Morse, maintained by the local American Legion chapter.

The rodeo grounds are not the only cultural properties in Drummond. The Mullan Road monument along the old highway is the oldest landmark. The local heritage museum is at the New Chicago School (1874), an frame one-story school moved from the Flint River Valley to its location near the interstate and turned into a museum.

The rodeo grounds are not the only cultural properties in Drummond. The Mullan Road monument along the old highway is the oldest landmark. The local heritage museum is at the New Chicago School (1874), an frame one-story school moved from the Flint River Valley to its location near the interstate and turned into a museum.

Another local museum emphasizes contemporary sculpture and painting by Bill Ohrmann. A latter day “cowboy artist” Ohrmann grew up in the Flint River Valley but by the 12960s he was producing sculpture and painting on a regular basis. The museum is also a gallery and his works are for sale, although the huge sculptures might not be going anywhere.

Another local museum emphasizes contemporary sculpture and painting by Bill Ohrmann. A latter day “cowboy artist” Ohrmann grew up in the Flint River Valley but by the 12960s he was producing sculpture and painting on a regular basis. The museum is also a gallery and his works are for sale, although the huge sculptures might not be going anywhere.

Montana Highway 1, designated the Pintler Scenic Route, has long been one of my favorite roads. It was the first Montana road to be paved in its entirety. During the state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, I documented the route as U.S. 10A, but once government officials decided to decommission the U.S. 10 designation in 1986, the name U.S. 10A also went away. t. In its early decades the route had passed through Opportunity to Anonconda onto Phillipsburg and then Drummond, but for all of my time in Montana, the highway has gone from Interstate I-90, Anaconda/Opportunity exit to the west and then north to the Drummond exit on the same interstate. There is a new 21st century rest stop center at the Anaconda I-90 exit that has a Montana Department of Transportation marker about the mountain ranges and the Pintler route.

Montana Highway 1, designated the Pintler Scenic Route, has long been one of my favorite roads. It was the first Montana road to be paved in its entirety. During the state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, I documented the route as U.S. 10A, but once government officials decided to decommission the U.S. 10 designation in 1986, the name U.S. 10A also went away. t. In its early decades the route had passed through Opportunity to Anonconda onto Phillipsburg and then Drummond, but for all of my time in Montana, the highway has gone from Interstate I-90, Anaconda/Opportunity exit to the west and then north to the Drummond exit on the same interstate. There is a new 21st century rest stop center at the Anaconda I-90 exit that has a Montana Department of Transportation marker about the mountain ranges and the Pintler route.

The town of Opportunity was not a priority for my travels in 1984-1985 but recent scholarship on how local residents have fought back against the decades of pollution from Anaconda’s Washoe Stack led me to give this small town of 500 a new look. The book is Brad Tyer’s Opportunity, Montana: Big Copper, Bad Water, and the Burial of an American Landscape (2014). Tyler details how the success of Anaconda also meant the sacrifice of thousands of surrounding acres to the pollution belching daily from the Washoe Stack until it closed in 1981. He then reviews in detail how in the 21st century, EPA heaped a new disaster on the town by moving Milltown wastes from the Clark’s Fork River near Missoula to Opportunity, telling locals that the Milltown soil would be new top soil for Opportunity. The environmental solution didn’t work, leaving the town in worse shape than before.

The town of Opportunity was not a priority for my travels in 1984-1985 but recent scholarship on how local residents have fought back against the decades of pollution from Anaconda’s Washoe Stack led me to give this small town of 500 a new look. The book is Brad Tyer’s Opportunity, Montana: Big Copper, Bad Water, and the Burial of an American Landscape (2014). Tyler details how the success of Anaconda also meant the sacrifice of thousands of surrounding acres to the pollution belching daily from the Washoe Stack until it closed in 1981. He then reviews in detail how in the 21st century, EPA heaped a new disaster on the town by moving Milltown wastes from the Clark’s Fork River near Missoula to Opportunity, telling locals that the Milltown soil would be new top soil for Opportunity. The environmental solution didn’t work, leaving the town in worse shape than before. Opportunity residents got a small fraction of SuperFund monies for the environmental cleanup in the form of Beaver Creek park. But the centerpiece of the park, the Opportunity School built for residents in 1914 by the Anaconda Company, has been mothballed for now. It operated from 1914 until the smelter ceased operations in 1981 and

Opportunity residents got a small fraction of SuperFund monies for the environmental cleanup in the form of Beaver Creek park. But the centerpiece of the park, the Opportunity School built for residents in 1914 by the Anaconda Company, has been mothballed for now. It operated from 1914 until the smelter ceased operations in 1981 and served as the community’s focal point. Restoration of the school is problematic due to the prior use of asbestos, meaning the federally funded park is only partially finished since the SuperFund support is now gone.

served as the community’s focal point. Restoration of the school is problematic due to the prior use of asbestos, meaning the federally funded park is only partially finished since the SuperFund support is now gone.

Sitting at 6,425 feet in elevation Georgetown Lake covers over 3700 acres. Today it is very much a recreational landscape but when it was created in 1885 its job was to generate electrical power for the nearby mines since it stood roughly equal distance between

Sitting at 6,425 feet in elevation Georgetown Lake covers over 3700 acres. Today it is very much a recreational landscape but when it was created in 1885 its job was to generate electrical power for the nearby mines since it stood roughly equal distance between

As the state highway historical marker above documents, this high country area was another mining region. With an vantage point above the lake, Southern Cross is a significant remnant of the mining activities from the early 20th century. The mines here

As the state highway historical marker above documents, this high country area was another mining region. With an vantage point above the lake, Southern Cross is a significant remnant of the mining activities from the early 20th century. The mines here began operation in the mid-1860s and production continued for until World War II. The settlement was largely Finnish and Swedish in the early 20th century when most of the remaining buildings were constructed.

began operation in the mid-1860s and production continued for until World War II. The settlement was largely Finnish and Swedish in the early 20th century when most of the remaining buildings were constructed.

Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity. Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte. The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair. The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it. Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks. The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.