As I carried out my new exploration and documentation of the Montana historic landscape from 2012 to 2016, there were new developments underway that I missed as I moved from one region to another during those years. The creation of Blackfoot Pathways: Sculpture in the Wild within a section of the national forest at Lincoln happened after I had revisited Lincoln–so I did not visit this exciting new sculpture park until May 2018. The park’s mission is to celebrate “the rich environmental and cultural heritage of the Blackfoot Valley through contemporary art practice.” Moving the TeePee Burner, which had stood for decades outside of the town between the Blackfoot River and Montana Highway 200, was the appropriate first step. This large metal structure once burned wood refuse from the Delaney and Sons sawmill–now it is the centerpiece of creative space set within the national forest just off of the highway.

The Gateway of Change (2014) by Jorn Ronnau of Denmark serves as an effective transition from the TeePee Burner to the other installations in the sculpture park. Casey Schachner’s Stringer (2017), below, is a great pine fan, recalling in its strength and lift the industrial works of the past.

My favorite installation in 2018 was the Picture Frame by Jaakko Frame of Finland, a massive interpretation of how we take nature and frame it constantly in our mind’s eye, or in our camera lens!

Another favorite was what seemed to be a trench, but is named the East West Passage (2015) by its creators, Mark Jacobs and Sam Clayton of the UK. The “walkable” structure creates a below-grade passage, giving a sense of direction in what can otherwise be a directionless landscape.

Tyler Nansen’s Bat Beacons (2016) at first glance seems redundant–why have pine poles installed in a pine forest? But Nansen wants to “encourage the preservation of bat habitats in Montana,” by creating possible roosts for bats with the black bat boxes at the top of each pole.

Frankly everything you encounter as you walk through this special landscape is interesting, if not thought provoking. And the artists are international, just as in the past the people who carved out the forests, dug the mines, and created towns came from across the globe. What an appropriate representation of the people who made the Blackfoot River Valley a distinctive place. In my earlier posts I have discussed how the

U. S. Forest Service really upped its game in public interpretation at historic sites from my fieldwork in the mid-1980s to the new survey of the mid-2010s. Blackfoot Pathways takes the interpretive experience in new and worthwhile directions, acknowledging the industrial past of the forests but also identifying new paths for the future.

I love Montana town signs, and Troy, deep in the state’s logging country, has one of the best. The sign lures to a city park nestled along the Kootenai River. The focus point is a

I love Montana town signs, and Troy, deep in the state’s logging country, has one of the best. The sign lures to a city park nestled along the Kootenai River. The focus point is a

the Great Northern’s main line, and I documented the few historic buildings left facing the railroad tracks today. The Home Bar (c. 1914) and the Club Bar were institutions then, and remain so today. The Kootenai State Bank building still stands but has experienced a major change to its facade–made better in part by the American flag painted over some of the frame addition.

the Great Northern’s main line, and I documented the few historic buildings left facing the railroad tracks today. The Home Bar (c. 1914) and the Club Bar were institutions then, and remain so today. The Kootenai State Bank building still stands but has experienced a major change to its facade–made better in part by the American flag painted over some of the frame addition. The Troy Jail, above, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and it remains the only building so listed in the town today. D.E. Crissey, a local contractor, built it out of concrete in 1924 during Troy’s boom from 1916 to 1926 when its population jumped from 300 to 1300. The Snowstorm mine, which produced lead, zinc, and silver, started to serve the demand for raw materials during World War I. The mine soon turned what had been a small railroad town into a mining camp best known for its brothels and bars. Then in the early 1920s the Great Northern decided to build a division point here, further booming the town. The Sandpoint Pole and Lumber Company began its logging business in 1923, and Troy suddenly was the largest town in the county

The Troy Jail, above, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and it remains the only building so listed in the town today. D.E. Crissey, a local contractor, built it out of concrete in 1924 during Troy’s boom from 1916 to 1926 when its population jumped from 300 to 1300. The Snowstorm mine, which produced lead, zinc, and silver, started to serve the demand for raw materials during World War I. The mine soon turned what had been a small railroad town into a mining camp best known for its brothels and bars. Then in the early 1920s the Great Northern decided to build a division point here, further booming the town. The Sandpoint Pole and Lumber Company began its logging business in 1923, and Troy suddenly was the largest town in the county

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed.

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed. Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west. Missoula County has grown, a lot, since my state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985, especially in the county seat of Missoula and surrounding suburbs. Yet Missoula County still has several spectacular rural drives, like Montana Highway 83 above at Condon, along with distinctive country towns. This post will share some of my favorites.

Missoula County has grown, a lot, since my state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985, especially in the county seat of Missoula and surrounding suburbs. Yet Missoula County still has several spectacular rural drives, like Montana Highway 83 above at Condon, along with distinctive country towns. This post will share some of my favorites.

The Condon Community Center and adjacent Swan Valley Community Library serve as additional hubs for those living along the lakes and mountains of northeast Missoula County. Both buildings are excellent examples of mid-20th century Rustic style–a look that, in different variations, dominates the Highway 35 corridor.

The Condon Community Center and adjacent Swan Valley Community Library serve as additional hubs for those living along the lakes and mountains of northeast Missoula County. Both buildings are excellent examples of mid-20th century Rustic style–a look that, in different variations, dominates the Highway 35 corridor.

Condon is also the base for the Condon Work Center, home to the Great Northern Fire Crew, of the Flathead National Forest. Here you can take a mile-long Swan Ecosystem Trail and learn of the diversity of life in this national forest region.

Condon is also the base for the Condon Work Center, home to the Great Northern Fire Crew, of the Flathead National Forest. Here you can take a mile-long Swan Ecosystem Trail and learn of the diversity of life in this national forest region. South of Condon on Montana Highway 83 is Seeley Lake–a place that certainly has boomed in the last 30 years–witness the improved highway, new businesses, and population that has increased over 60 percent since my last visit in 1992. Yet it still had places rooted in the community’s earlier history such as the Sullivan Memorial Community Hall–a good example of mid-20th century Rustic style.

South of Condon on Montana Highway 83 is Seeley Lake–a place that certainly has boomed in the last 30 years–witness the improved highway, new businesses, and population that has increased over 60 percent since my last visit in 1992. Yet it still had places rooted in the community’s earlier history such as the Sullivan Memorial Community Hall–a good example of mid-20th century Rustic style. And it had added one of my favorite bits of roadside architecture in this part of Montana: the Chicken Coop Restaurant as well as opening a new Seeley Lake Historical Museum and Chamber of Commerce office at a spectacular highway location just outside of town.

And it had added one of my favorite bits of roadside architecture in this part of Montana: the Chicken Coop Restaurant as well as opening a new Seeley Lake Historical Museum and Chamber of Commerce office at a spectacular highway location just outside of town.

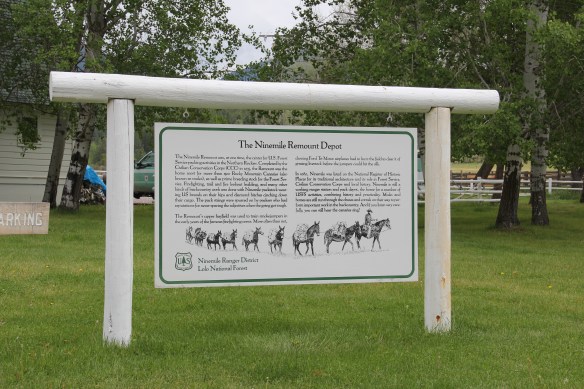

I don’t recall even thinking about the forest service facility, but here was an entire complex devoted to the forest service’s use of mules and horses before the days of the ATV that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The remount depot is an interesting

I don’t recall even thinking about the forest service facility, but here was an entire complex devoted to the forest service’s use of mules and horses before the days of the ATV that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The remount depot is an interesting

The name Frenchtown dates to 1868 and is a reference to a number of French Canadians who moved here in the early settlement period. A National Register-listed church, the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (1884) marks that first generation of settlers. Its classical-tinged cupola has long been the town’s most famous landmark.

The name Frenchtown dates to 1868 and is a reference to a number of French Canadians who moved here in the early settlement period. A National Register-listed church, the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (1884) marks that first generation of settlers. Its classical-tinged cupola has long been the town’s most famous landmark. The Milwaukee Road built through here in 1907-1908 and there remains a handful of historic business buildings from the time of the Milwaukee boom. There is one landmark

The Milwaukee Road built through here in 1907-1908 and there remains a handful of historic business buildings from the time of the Milwaukee boom. There is one landmark

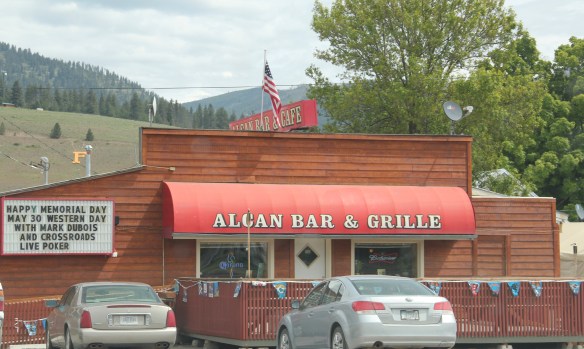

another roadside landmark–the Bucksnort Bar, just further evidence to add to the Chicken Coop and the Alcan that you won’t go hungry if you explore the small towns of Missoula County.

another roadside landmark–the Bucksnort Bar, just further evidence to add to the Chicken Coop and the Alcan that you won’t go hungry if you explore the small towns of Missoula County.

Montana Highway 141 cuts north from Avon On U. S. Highway 12 to halfway between the towns of Ovando and Lincoln on Montana Highway 200. Its is high mountains prairie travel at its best, although the height of ranching along this route disappeared a while back. About 12-13 miles north of Avon you cross into the Nevada Creek drainage, which has long watered the land, enhanced after the New Deal added the Nevada Creek earthen dam that created Nevada Creek Reservoir in 1938.

Montana Highway 141 cuts north from Avon On U. S. Highway 12 to halfway between the towns of Ovando and Lincoln on Montana Highway 200. Its is high mountains prairie travel at its best, although the height of ranching along this route disappeared a while back. About 12-13 miles north of Avon you cross into the Nevada Creek drainage, which has long watered the land, enhanced after the New Deal added the Nevada Creek earthen dam that created Nevada Creek Reservoir in 1938.

Along the east banks of the lake are remnants of the Fitzpatrick Ranch, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I highlighted the property in my book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986). Jimmy Isbel established the property in 1872,

Along the east banks of the lake are remnants of the Fitzpatrick Ranch, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I highlighted the property in my book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986). Jimmy Isbel established the property in 1872,

Thirty years ago, this significant collection of vernacular buildings was in good condition, but the years since have been hard on the property, and the complex now needs serious preservation attention. The loss of the roof on the log barn, and the general poor condition of the roofs of the outbuildings are major concerns.

Thirty years ago, this significant collection of vernacular buildings was in good condition, but the years since have been hard on the property, and the complex now needs serious preservation attention. The loss of the roof on the log barn, and the general poor condition of the roofs of the outbuildings are major concerns.

Between the Fitzpatrick Ranch and Helmville is the Barger Ranch, also from the late 19th century judging from the more polished example of Queen Anne style in the ranch house. It is living proof that not all of the Nevada Creek ranches have passed away. The Nevada Creek Water Users Association at Helmville still operates to distribute the invaluable water from the reservoir.

Between the Fitzpatrick Ranch and Helmville is the Barger Ranch, also from the late 19th century judging from the more polished example of Queen Anne style in the ranch house. It is living proof that not all of the Nevada Creek ranches have passed away. The Nevada Creek Water Users Association at Helmville still operates to distribute the invaluable water from the reservoir.  Helmville was another topic in my 1986 book. Throughout the Nevada Creek drainage, you could help but be impressed with the log construction, and the various types of notching used for the buildings. Helmville had a particular interesting grouping of wood frame and log buildings, which were highlighted by a 1984 photograph in the book. That exact view could not be replicated 30 years later but several of the old buildings still stood.

Helmville was another topic in my 1986 book. Throughout the Nevada Creek drainage, you could help but be impressed with the log construction, and the various types of notching used for the buildings. Helmville had a particular interesting grouping of wood frame and log buildings, which were highlighted by a 1984 photograph in the book. That exact view could not be replicated 30 years later but several of the old buildings still stood.

Helmville has a good bit of continuity. Along with the row of buildings on Montana 271 there is a turn of the 20th century gable-front cottage and a two-story lodge building that has been turned into a garage.

Helmville has a good bit of continuity. Along with the row of buildings on Montana 271 there is a turn of the 20th century gable-front cottage and a two-story lodge building that has been turned into a garage.

Trixie’s was the same fun dive that I always recalled, but the village’s historic buildings had been restored, looking good. Business appeared to be brisk. A new community church has been opened, and a major interpretive place for the “Lewis Minus Clark” expedition had been installed. Kudos to both the U.S. Forest Service and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail for allowing a bit of humor in this marker.

Trixie’s was the same fun dive that I always recalled, but the village’s historic buildings had been restored, looking good. Business appeared to be brisk. A new community church has been opened, and a major interpretive place for the “Lewis Minus Clark” expedition had been installed. Kudos to both the U.S. Forest Service and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail for allowing a bit of humor in this marker.

The school had also expanded from its New Deal core of the 1930s, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration. But the most noticeable change was the town’s street signs–first the fact that a small place had street signs but then the nostalgic backpacker theme of these cast iron marvels.

The school had also expanded from its New Deal core of the 1930s, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration. But the most noticeable change was the town’s street signs–first the fact that a small place had street signs but then the nostalgic backpacker theme of these cast iron marvels. Ovando is a good location on the Blackfoot River for sportsmen, anglers, and hikers headed into the Bob Marshall Wilderness–its recent change demonstrates the influence on those groups on the 21st century Montana landscape.

Ovando is a good location on the Blackfoot River for sportsmen, anglers, and hikers headed into the Bob Marshall Wilderness–its recent change demonstrates the influence on those groups on the 21st century Montana landscape.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters. The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory.

The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory. The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century.

The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century. Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history. Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses.

Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses. In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

The late 19th century discovery and development of silver mines high in the Granite Mountains changed the course of this part of the Pintler route. The Granite Mountain mines yielded one of the biggest silver strikes in all of Montana, creating both the mountain mining town of Granite and a bit farther down on the mountain’s edge the town of Philipsburg, which by 1893 served as the seat for the new county of Granite.

The late 19th century discovery and development of silver mines high in the Granite Mountains changed the course of this part of the Pintler route. The Granite Mountain mines yielded one of the biggest silver strikes in all of Montana, creating both the mountain mining town of Granite and a bit farther down on the mountain’s edge the town of Philipsburg, which by 1893 served as the seat for the new county of Granite. The U.S. Forest Service’s rather weathered and beat-up sign marks the historic entrance to the mining town of Granite, located at over 7,000 feet in elevation above the town of Philipsburg. During the 1984-85 state historic preservation plan work Granite was the focal point. The office knew of the latest collapse of Miners Union Hall (1890) turning what had been an impressive Victorian landmark into a place with three walls and lots of rubble–it remains that way today.

The U.S. Forest Service’s rather weathered and beat-up sign marks the historic entrance to the mining town of Granite, located at over 7,000 feet in elevation above the town of Philipsburg. During the 1984-85 state historic preservation plan work Granite was the focal point. The office knew of the latest collapse of Miners Union Hall (1890) turning what had been an impressive Victorian landmark into a place with three walls and lots of rubble–it remains that way today.

Connecting the Granite road to the town of Philipsburg, today as in the past, is the site of the Bi-Metallic Mill, which is still in limited use today compared to the mining hey-day.

Connecting the Granite road to the town of Philipsburg, today as in the past, is the site of the Bi-Metallic Mill, which is still in limited use today compared to the mining hey-day.

As the historic promotional image above conveys, the Bitterroot Valley is an agricultural wonderland, but one dependent on irrigation and agricultural science. This image is on display at the Ravalli County Museum, which is located in the historic county courthouse from the turn of the 20th century.

As the historic promotional image above conveys, the Bitterroot Valley is an agricultural wonderland, but one dependent on irrigation and agricultural science. This image is on display at the Ravalli County Museum, which is located in the historic county courthouse from the turn of the 20th century. Local ranchers and boosters understood the economic potential of the valley if the land was properly nurtured. Some of the best evidence today is along the Eastside Highway,

Local ranchers and boosters understood the economic potential of the valley if the land was properly nurtured. Some of the best evidence today is along the Eastside Highway,

railroad spur through the valley. With its Four-Square style dwelling, the Bailey Ranch, immediately above, is a good example of the places of the 1910s-1920s. The Popham Ranch, seen below, is one of the oldest, dating to 1882.

railroad spur through the valley. With its Four-Square style dwelling, the Bailey Ranch, immediately above, is a good example of the places of the 1910s-1920s. The Popham Ranch, seen below, is one of the oldest, dating to 1882.

One major change in the Bitterroot over 30 years is the fruit industry has diminished and how many more small ranches and suburban-like developments crowd the once expansive agricultural wonderlands of the Bitterroot. The dwindling number that remain deserve careful attention for their future conservation before the working landscape disappears.

One major change in the Bitterroot over 30 years is the fruit industry has diminished and how many more small ranches and suburban-like developments crowd the once expansive agricultural wonderlands of the Bitterroot. The dwindling number that remain deserve careful attention for their future conservation before the working landscape disappears.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole. There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.

There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley.

Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley. At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93. And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

And the coffee is always hot, and strong. Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area. Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.