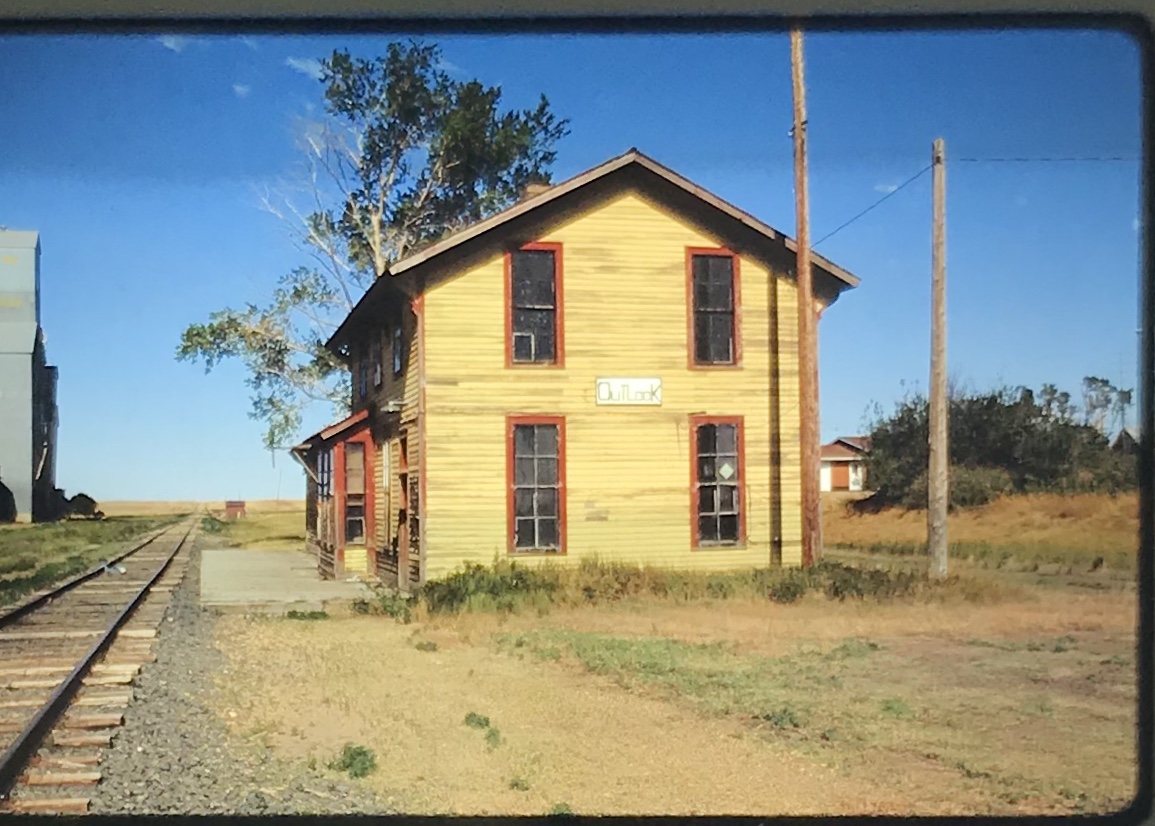

When I carried out the 1984-1985 survey of Montana as part of the state historic preservation planning process, one resource was at the forefront of my mind–railroad passenger stations. Not only had recent scholarship by John Hudson and John Stilgoe brought new interest to the topic, there had been the recent bankruptcy of the Milwaukee Road, and the end of passenger service in large parts of the state, except along the Hi-Line of the old Great Northern Railway (where Amtrak still runs today.)

The mid-20th century standardized design for Great Northern stations at Chester on US 2.

Some of the passenger stations in the major cities had already been converted into new uses, such as restaurants, offices, and various downtown commercial uses. The lovely turn of the twentieth century stations for the Great Northern (left) and the Milwaukee Road (right) in Great Falls showed how the location of the buildings, plus their

architectural quality and the amount of available space made them perfect candidates for adaptive reuse. While the tenants have changed over the past 30 plus years, both buildings still serve as heritage anchors for the city. While success marked early adaptive reuse projects in Great Falls and Missoula, for instance, it was slow to come to Montana’s largest city–the neoclassical styled Northern Pacific depot was abandoned and

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

In the 1984-1985 I documented hundreds of railroad depots across Big Sky Country. From 2012-2015 I noted how many had disappeared–an opportunity to preserve heritage and put a well-located substantial building for the building back to work had been wasted. But I also came away with a deep appreciation of just how many types of new lives train stations could have.

Turning iconic buildings into community museums is a time-honored tradition, as you can find at the magnificent Northern Pacific station at Livingston, shown above. A handful of Montana communities have followed that tradition–I am especially glad that people in Harlowton and Wheatland County banded together to preserve the

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

But there are so many other uses–as they know in Lewistown. Already in the mid-1980s investors in Lewistown had turned the old Milwaukee Road station, shown above, into a hotel and conference center, the Yogo Inn. When I visited Lewistown in 2013 the Yogo was undergoing a facelift after 30 years as a commercial business. The town’s other

historic depot, a substantial brick building (above) from the Great Northern Railway, was a gas station, convenience mart, office building, and store, all in one.

Deer Lodge is blessed with both of its historic depots. The Milwaukee Road depot has become a church while the Northern Pacific depot became the Powell County Senior Citizens Center. Indeed, converting such a community landmark into a community center is popular in other Montana towns, such as the National Register-listed passenger station shown below in Kevin, Toole County, near the border with Canada.

One of the most encouraging trends of this century is how many families have turned depots into their homes–you can’t beat the location and the long, horizontal nature of the often-found combination depot (passenger station and luggage warehouse in same building) means that these dwellings have much in common with the later Ranch-style houses of the 1950s and 1960s.

A former Great Northern depot in Windham.

A Milwaukee Road depot turned into a home in Rosebud County.

But in my work from 2012-15 I found more and more examples of how local entrepreneurs have turned these historic buildings into businesses–from a very simple, direct conversion from depot to warehouse in Grassrange to the use of the Milwaukee Road depot in Roundup as the local electric company office.

As these last examples attest–old buildings can still serve communities, economically and gracefully. Not all historic preservation means the creation of a museum–that is the best course in only a few cases. But well-built and maintained historic buildings can be almost anything else–the enduring lesson of adaptive reuse

One of the very few historical markers in Montana that touches on the state’s irrigation history focuses about a historic bridge that once stood nearby at Tampico.

One of the very few historical markers in Montana that touches on the state’s irrigation history focuses about a historic bridge that once stood nearby at Tampico.

Large man-made lakes capture water to reserve it for use throughout the growing season. The images above are of Fresno Reservoir, on a rainy morning, in Hill County. While the two images below are of Nelson Reservoir, on a typically bright sunny day, many miles downstream in Phillips County.

Large man-made lakes capture water to reserve it for use throughout the growing season. The images above are of Fresno Reservoir, on a rainy morning, in Hill County. While the two images below are of Nelson Reservoir, on a typically bright sunny day, many miles downstream in Phillips County.

The Milk River Project shapes so much of the Hi-Line, it has become just part of the scenery. I wonder how many travelers along U.S. Highway 2 in Phillips County even notice or consider the constant presence of the ditch along their route.

The Milk River Project shapes so much of the Hi-Line, it has become just part of the scenery. I wonder how many travelers along U.S. Highway 2 in Phillips County even notice or consider the constant presence of the ditch along their route.

is a tiny place, almost 20 miles from the county seat of Malta. But at the time of the Milk River Project, Dodson was vital; the ditch neatly divided the town into two halves, and a major diversion dam was just west of town. Here was a perfect place, at the turn of the century, for a fairgrounds. And it is a gorgeous historic fairgrounds.

is a tiny place, almost 20 miles from the county seat of Malta. But at the time of the Milk River Project, Dodson was vital; the ditch neatly divided the town into two halves, and a major diversion dam was just west of town. Here was a perfect place, at the turn of the century, for a fairgrounds. And it is a gorgeous historic fairgrounds.

Lehman, west of Chinook adjacent to both the Milk River and U.S. Highway 2, has almost totally disappeared as a place along the tracks. What is left of the town–this deteriorating commercial building in 2013–might even be gone today.

Lehman, west of Chinook adjacent to both the Milk River and U.S. Highway 2, has almost totally disappeared as a place along the tracks. What is left of the town–this deteriorating commercial building in 2013–might even be gone today.

modern style for many Catholic churches in eastern Montana. The Culbertson church is a good example of that pattern. Another church that belongs to the modern design era of the 20th century is Trinity Lutheran Church, especially as this distinguished building expanded over the decades to meet its congregation’s needs.

modern style for many Catholic churches in eastern Montana. The Culbertson church is a good example of that pattern. Another church that belongs to the modern design era of the 20th century is Trinity Lutheran Church, especially as this distinguished building expanded over the decades to meet its congregation’s needs.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

The town’s grain elevators really are its landmark–the town is along the railroad spur and sits off Montana Highway 16–without the elevators you might not even notice it.

The town’s grain elevators really are its landmark–the town is along the railroad spur and sits off Montana Highway 16–without the elevators you might not even notice it. Agriculture defines the use of the largest buildings of the town, and while it is a tiny place Reserve serves a much larger region of ranches located between Plentywood, the county seat, to the north and Medicine Lake, to the south.

Agriculture defines the use of the largest buildings of the town, and while it is a tiny place Reserve serves a much larger region of ranches located between Plentywood, the county seat, to the north and Medicine Lake, to the south. This larger audience for services in Reserve helps to explain the survival of the Reserve Post Office–so many tiny Montana towns have lost the one federal institution that had been there since the town’s beginning.

This larger audience for services in Reserve helps to explain the survival of the Reserve Post Office–so many tiny Montana towns have lost the one federal institution that had been there since the town’s beginning. But naturally I will urge you to make a stop, however brief, at the Reserve Bar. This concrete block building, with its period glass block windows, is a friendly place, and a great way to talk with both residents and surrounding farmers.

But naturally I will urge you to make a stop, however brief, at the Reserve Bar. This concrete block building, with its period glass block windows, is a friendly place, and a great way to talk with both residents and surrounding farmers.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89.

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89. Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta  won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined?

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined? Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.