Hinsdale (just over 200 people in Valley County) and Saco (just under 200 people in Phillips County) are two country towns along the Hi-Line between the much larger county seats of Glasgow and Malta. I have little doubt that few visitors ever stop, or even slow down much, as they speed along the highway. Both towns developed as railroad stops along the Great Northern Railway–the image above shows how close the highway and railroad tracks are along this section of the Hi-Line. Both largely served, and still

serve, historic ranches, such as the Robinson Ranch, established in 1891, in Phillips County. Both towns however have interesting buildings, and as long as they keep their community schools, both will survive in the future.

Hinsdale School, Valley County

Saco School, Phillips County

Of the two towns, I have discussed Saco to a far greater extent in this blog because it was one of my “targeted” stops in the 1984 survey. The State Historic Preservation Office at the Montana Historical Society had received inquiries from local residents in Saco about historic preservation alternatives and I was there to take a lot of images to share back with the preservationists in Helena. But in my earlier posts, I neglected two community

buildings, the rather different design of the post office from the 1960s and the vernacular Gothic beauty of the historic Methodist Church, especially the Victorian brackets of its bell tower.

buildings, the rather different design of the post office from the 1960s and the vernacular Gothic beauty of the historic Methodist Church, especially the Victorian brackets of its bell tower.

I ignored Hinsdale almost totally in its first posting, focusing on roadside murals. This Valley County town is worth a second look, if just for its two historic bank buildings. The former First National Bank and the former Valley County Bank both speak to the hopes for growth along this section of the Milk River Project of the U.S. Reclamation Service in the early 20th century. Architecturally both buildings were touched by the Classical Revival style, and both took the “strongbox” form of bank buildings that you can find throughout the midwest and northern plains in the first two decades of the 20th century.

The rest of Hinsdale’s “commercial district” has the one-story “false-front” buildings often found in country railroad towns along the Hi-Line.

Local residents clearly demonstrate their sense of community not only through the school, which stands at the of the commercial area. But community pride also comes through in such buildings as the c. 1960s American Legion Hall, the c. 1902 Methodist church (the separated cupola must be a good story), and St. Anthony’s Catholic Church.

These small railroad towns of the Hi-Line have been losing population for decades, yet they remain, and the persistence of these community institutions helps to explain why.

The county library, above, is small but busy, a reminder of how important these public buildings can be. About 5 years ago, the time of my last visit, Scobey still had its own medical center, below, as well as a distinctive post office, different from many in the region due to its modernist style.

The county library, above, is small but busy, a reminder of how important these public buildings can be. About 5 years ago, the time of my last visit, Scobey still had its own medical center, below, as well as a distinctive post office, different from many in the region due to its modernist style.

But like most travelers I roar down the highway, perhaps noting the tall grain elevators facing the town proper, and pay little attention to anything else. In a post of four years ago, I spoke of Golden Valley County and its historic landmarks, highlighting the grain elevators, the Golden Valley Courthouse, the Sims-Garfield historic ranch, and the historic town bar in Ryegate. But like the other eastern Montana county seats, Ryegate deserves a closer look.

But like most travelers I roar down the highway, perhaps noting the tall grain elevators facing the town proper, and pay little attention to anything else. In a post of four years ago, I spoke of Golden Valley County and its historic landmarks, highlighting the grain elevators, the Golden Valley Courthouse, the Sims-Garfield historic ranch, and the historic town bar in Ryegate. But like the other eastern Montana county seats, Ryegate deserves a closer look.

Ryegate received one of the standardized “modern” post office designs from the federal government in the 1970s–the town’s fortunes have remained basically frozen after the Milwaukee Road declared bankruptcy and shut down the tracks in 1980.

Ryegate received one of the standardized “modern” post office designs from the federal government in the 1970s–the town’s fortunes have remained basically frozen after the Milwaukee Road declared bankruptcy and shut down the tracks in 1980.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors. Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

St. Joseph Catholic Church, perched now on a barren bluff facing the lake, was moved about 2.5 miles east to its present location in 1954. Originally near the river in what was then known as the Canton Valley settlement, the church building is one of the state’s oldest, dating to 1874-1875 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The proud Gothic styled church is the remnant of one of the valley’s earliest settlements.

St. Joseph Catholic Church, perched now on a barren bluff facing the lake, was moved about 2.5 miles east to its present location in 1954. Originally near the river in what was then known as the Canton Valley settlement, the church building is one of the state’s oldest, dating to 1874-1875 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The proud Gothic styled church is the remnant of one of the valley’s earliest settlements.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

Montana’s gateways into Yellowstone National Park are known far and wide. The most popular are associated with the trains that delivered mostly easterners to the wonderland of the park–West Yellowstone for the Union Pacific line and Gardiner for the Northern Pacific Railway.

Montana’s gateways into Yellowstone National Park are known far and wide. The most popular are associated with the trains that delivered mostly easterners to the wonderland of the park–West Yellowstone for the Union Pacific line and Gardiner for the Northern Pacific Railway. Cooke City, located in the corner of Park County, was never a railroad town but an overland connection that did not become popular until the development of the Beartooth Highway out of Red Lodge in the 1920s.

Cooke City, located in the corner of Park County, was never a railroad town but an overland connection that did not become popular until the development of the Beartooth Highway out of Red Lodge in the 1920s. It is all about the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) here–when it opens, Cooke City booms as a tourism oasis. When the highway closes for its long winter, business doesn’t end since the road to Mammoth Hot Springs far to the west is kept open as best as it can be, but the number of visitors drops remarkably. Snow mobile traffic in the winter has meant a lot to local business in the last 30 years.

It is all about the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) here–when it opens, Cooke City booms as a tourism oasis. When the highway closes for its long winter, business doesn’t end since the road to Mammoth Hot Springs far to the west is kept open as best as it can be, but the number of visitors drops remarkably. Snow mobile traffic in the winter has meant a lot to local business in the last 30 years.

Cooke City uses its mining past to define its identity today, from moving log mining shacks and cabins into town, as shown above, for potential new lures for tourism, to the recently established visitor center and museum, which includes some of the local mining

Cooke City uses its mining past to define its identity today, from moving log mining shacks and cabins into town, as shown above, for potential new lures for tourism, to the recently established visitor center and museum, which includes some of the local mining

Perhaps the best example is the rustic yet modern styling of the Mt Republic Chapel of Peace between Silver Gate and Cooke City on U.S. 212. It is no match for the soaring mountains that surround it but its quiet dignity reflects well the people and environment of this part of Montana.

Perhaps the best example is the rustic yet modern styling of the Mt Republic Chapel of Peace between Silver Gate and Cooke City on U.S. 212. It is no match for the soaring mountains that surround it but its quiet dignity reflects well the people and environment of this part of Montana.

The same can be said for Hoosier’s Bar–a favorite haunt here in Cooke City for several decades, easy to find with its neon sign, and then there is the throwback telephone booth–a good idea since many cell phones search for coverage in this area. Cooke City and Silver Gate are the smallest Montana gateways into Yellowstone National Park but they tell and preserve their story well.

The same can be said for Hoosier’s Bar–a favorite haunt here in Cooke City for several decades, easy to find with its neon sign, and then there is the throwback telephone booth–a good idea since many cell phones search for coverage in this area. Cooke City and Silver Gate are the smallest Montana gateways into Yellowstone National Park but they tell and preserve their story well. Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

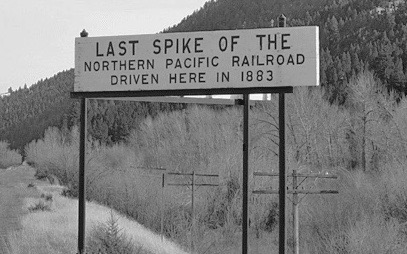

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters. The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory.

The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory. The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century.

The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century. Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history. Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses.

Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses. In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.