On Bozeman’s Main Street today there is a huge mural celebrating the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1882. The impact of the railroad on the town was certainly a topic of interest in the 1984-85 survey, and one image included the existing Northern Pacific Railroad and adjoining grain elevators and other businesses reliant on the corridor.

On Bozeman’s Main Street today there is a huge mural celebrating the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1882. The impact of the railroad on the town was certainly a topic of interest in the 1984-85 survey, and one image included the existing Northern Pacific Railroad and adjoining grain elevators and other businesses reliant on the corridor. Today that same place has been transformed, through adaptive reuse, into a micro-brewery and restaurant–pretty good place too, and a great place in 2015 for me to get out of a persistent rain. The Northern Pacific reached a deal with rancher Nelson Story in 1882 to build through his property but also provide a spur line to his existing mill operations. From the beginning both the railroad and local entrepreneurs saw an agricultural future for Bozeman and Gallatin County.

Today that same place has been transformed, through adaptive reuse, into a micro-brewery and restaurant–pretty good place too, and a great place in 2015 for me to get out of a persistent rain. The Northern Pacific reached a deal with rancher Nelson Story in 1882 to build through his property but also provide a spur line to his existing mill operations. From the beginning both the railroad and local entrepreneurs saw an agricultural future for Bozeman and Gallatin County.

A similar re-energized future has not yet happened for Bozeman’s historic Northern Pacific passenger depot. The depot is a turn of the 20th century brick building that received a remodeling and expansion from Bozeman architect Fred Willson c. 1922 that turned it into a fashionable (and for the Northern Pacific line, a rare) example of Prairie style in a railroad building.

The depot and adjoining buildings have been designated as a historic district, with a pocket city park providing some new life to the area. But this impressive building’s next life remains uncertain even as the city encourages creative solutions for the area.

The depot and adjoining buildings have been designated as a historic district, with a pocket city park providing some new life to the area. But this impressive building’s next life remains uncertain even as the city encourages creative solutions for the area.

The c. 1922 depot is adequately moth-balled–the new roof has lots of life left–and as the city maintains it is structurally sound with key interior features intact. Yet graffiti now mars one end of the building, and any building that is empty, especially in such a booming local economy, is cause for concern.

The c. 1922 depot is adequately moth-balled–the new roof has lots of life left–and as the city maintains it is structurally sound with key interior features intact. Yet graffiti now mars one end of the building, and any building that is empty, especially in such a booming local economy, is cause for concern.

Why? Because Bozeman has a tradition of tearing down historic railroad depots. The images above from 1985 were of the town’s Milwaukee Road depot (c. 1907). It was abandoned then, and I was concerned because so many of the railroad’s buildings had already disappeared across Montana, and because the arrival of the Milwaukee Road in Bozeman had launched an economic boom that shaped the town from 1907 to 1920. In 2003, despite howls of protest, the building was demolished–a new use for it had never been found.

The same fate did not befell the Milwaukee Road’s other significant building in Bozeman, its concrete block warehouse, shown above in an 1985 image. The open space, solid construction, and excellent location helped to ensure a much longer life for the building, which is now a building supplies store, with a repainted company sign adorning the elevations of the building.

The same fate did not befell the Milwaukee Road’s other significant building in Bozeman, its concrete block warehouse, shown above in an 1985 image. The open space, solid construction, and excellent location helped to ensure a much longer life for the building, which is now a building supplies store, with a repainted company sign adorning the elevations of the building.

It is encouraging that the city recognizes the significance, and the possibilities, for the historic buildings along Bozeman’s railroad corridor. Let’s hope that a permanent solution soon emerges for the empty Northern Pacific depot.

It is encouraging that the city recognizes the significance, and the possibilities, for the historic buildings along Bozeman’s railroad corridor. Let’s hope that a permanent solution soon emerges for the empty Northern Pacific depot.

Willow Creek was the end of the line for both the Northern Pacific and Milwaukee Road railroads as they vied for dominance in turn of the 20th century western Gallatin County. The Northern Pacific came first with its spur line to Butte in the late 1880s then the Milwaukee arrived c. 1908. Both used the same corridor, along what is now called the Old Yellowstone Trail on some maps; the Willow Creek Road (MT 287) on others. It was a route that dated to 1864–the town cemetery, according to lore, dates to that year and Willow Creek has had a post office since 1867.

Willow Creek was the end of the line for both the Northern Pacific and Milwaukee Road railroads as they vied for dominance in turn of the 20th century western Gallatin County. The Northern Pacific came first with its spur line to Butte in the late 1880s then the Milwaukee arrived c. 1908. Both used the same corridor, along what is now called the Old Yellowstone Trail on some maps; the Willow Creek Road (MT 287) on others. It was a route that dated to 1864–the town cemetery, according to lore, dates to that year and Willow Creek has had a post office since 1867.

Across the street is the “employment center,” the Willow Creek Tool and Technology which sells its wares across the west out of its brick building from the 1910s. (Note the faded advertising sign that once greeted travelers on the Yellowstone Trail highway.)

Across the street is the “employment center,” the Willow Creek Tool and Technology which sells its wares across the west out of its brick building from the 1910s. (Note the faded advertising sign that once greeted travelers on the Yellowstone Trail highway.) The cultural side of Willow Creek is represented by several places: homes and galleries of different artists, a monthly arts festival in the summer, and two special buildings from the 1910s. The Stateler Memorial Methodist Church, c. 1915, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built from rusticated concrete blocks (from the cement factory at Three Forks) designed to resemble stone masonry, the church building is home to one of the oldest congregations (1864) in the Methodist Church in Montana. The Gothic Revival-styled sanctuary is named in honor of its founding minister Learner B. Stateler.

The cultural side of Willow Creek is represented by several places: homes and galleries of different artists, a monthly arts festival in the summer, and two special buildings from the 1910s. The Stateler Memorial Methodist Church, c. 1915, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built from rusticated concrete blocks (from the cement factory at Three Forks) designed to resemble stone masonry, the church building is home to one of the oldest congregations (1864) in the Methodist Church in Montana. The Gothic Revival-styled sanctuary is named in honor of its founding minister Learner B. Stateler. Nearby is another crucial landmark for any rural Montana community–the local school. The Willow Creek School is an excellent example of the standardized, somewhat Craftsman-styled designs used for rural Montana schools in the 1910s. Two stories of classrooms, sitting on a full basement, was a large school for its time, another reflection of the hopes of the homesteading era.

Nearby is another crucial landmark for any rural Montana community–the local school. The Willow Creek School is an excellent example of the standardized, somewhat Craftsman-styled designs used for rural Montana schools in the 1910s. Two stories of classrooms, sitting on a full basement, was a large school for its time, another reflection of the hopes of the homesteading era. Additions in form of a gym and added rooms had come to the north and the school and its lot is the town’s community center. Although so close to Three Forks, the school kept its

Additions in form of a gym and added rooms had come to the north and the school and its lot is the town’s community center. Although so close to Three Forks, the school kept its

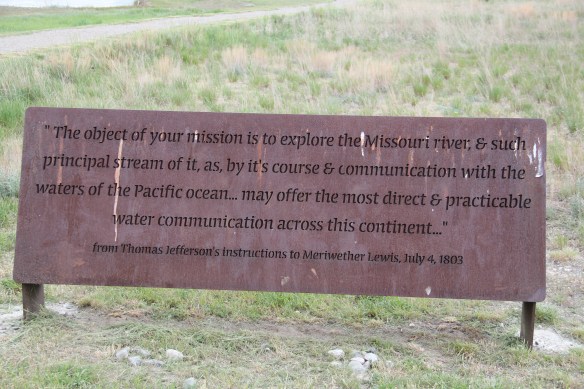

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks. The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

Located between the Gallatin River and Interstate I-90, Logan is a forgotten yet still historically significant railroad junction on the Northern Pacific Railroad. Established c.

Located between the Gallatin River and Interstate I-90, Logan is a forgotten yet still historically significant railroad junction on the Northern Pacific Railroad. Established c.

Manhattan was not originally Manhattan, but named Moreland, as discussed in an earlier blog about the effort to build a barley empire in this part of Gallatin County at the turn of the century by the Manhattan Malting Company and its industrial works here and in Bozeman. But the existing railroad corridor, along with the surviving one- and two-

Manhattan was not originally Manhattan, but named Moreland, as discussed in an earlier blog about the effort to build a barley empire in this part of Gallatin County at the turn of the century by the Manhattan Malting Company and its industrial works here and in Bozeman. But the existing railroad corridor, along with the surviving one- and two-

The historic auto garage from c. 1920 above is one of the most significant landmarks left upon old U.S. 10, and I am glad it is still used for its original function in the 21st century.

The historic auto garage from c. 1920 above is one of the most significant landmarks left upon old U.S. 10, and I am glad it is still used for its original function in the 21st century.

But it has many positives in place to keep its character yet change with the times. Many residents are using historic buildings for their businesses and trades. Others are clearly committed to the historic residential area–you can’t help but be impressed by the town’s well-kept historic homes and well-maintained yards and public areas.

But it has many positives in place to keep its character yet change with the times. Many residents are using historic buildings for their businesses and trades. Others are clearly committed to the historic residential area–you can’t help but be impressed by the town’s well-kept historic homes and well-maintained yards and public areas.

From 1983-85 Belgrade became one of my favorite Northern Pacific railroad towns. Often I would leave the interstate here, stop at truly one of the great small town bars/cafes along the town’s railroad corridors, and then travel on old U.S. 10 (the town’s Main Street) on to Manhattan, Logan, and Three Forks before popping up on US 287 and continuing to home in Helena.

From 1983-85 Belgrade became one of my favorite Northern Pacific railroad towns. Often I would leave the interstate here, stop at truly one of the great small town bars/cafes along the town’s railroad corridors, and then travel on old U.S. 10 (the town’s Main Street) on to Manhattan, Logan, and Three Forks before popping up on US 287 and continuing to home in Helena.

Despite the boom, several landmarks remain. The Belgrade Community Church, built in 1904 as the town’s Presbyterian church, served in the 1980s as a joint church building for both the town’s Presbyterians and Baptists. This impressive Gothic Revival building had received several updates and additions in the mid-1970s. It became the Community Church in 1992 as the Presbyterians left and the American Baptist Church took over sole control of this historic church building.

Despite the boom, several landmarks remain. The Belgrade Community Church, built in 1904 as the town’s Presbyterian church, served in the 1980s as a joint church building for both the town’s Presbyterians and Baptists. This impressive Gothic Revival building had received several updates and additions in the mid-1970s. It became the Community Church in 1992 as the Presbyterians left and the American Baptist Church took over sole control of this historic church building.

The two lanes of U.S. Highway 89 as it winds northwest from Choteau to the southern boundary of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, cross a stark yet compelling landscape, a jaunt that has never ceased to amaze me. To those only with the mountains of Glacier National Park in their minds will see merely open land, irrigated fields, scattered ranches.

The two lanes of U.S. Highway 89 as it winds northwest from Choteau to the southern boundary of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, cross a stark yet compelling landscape, a jaunt that has never ceased to amaze me. To those only with the mountains of Glacier National Park in their minds will see merely open land, irrigated fields, scattered ranches. But there’s a deeper landscape here, some embodied in the tiny towns along the way, others in places just ignored, certainly not recognized. In the first post of 2016, and the 200th of this series of explorations of the Montana landscape, let’s once again look a bit harder.

But there’s a deeper landscape here, some embodied in the tiny towns along the way, others in places just ignored, certainly not recognized. In the first post of 2016, and the 200th of this series of explorations of the Montana landscape, let’s once again look a bit harder. For one, this is a landscape shaped by Cold War America. Nuclear missile silos were installed throughout the region with some easily accessible from the roadway. You wonder how many tourists realize that.

For one, this is a landscape shaped by Cold War America. Nuclear missile silos were installed throughout the region with some easily accessible from the roadway. You wonder how many tourists realize that. The federal imprint has lingered on this land for almost 150 years. Today north of Choteau this highway historical marker, and a lonely boulder set square in the adjacent field, mark the first federal intrusion, the creation of the Teton River Agency, where in 1868-69 the federal government established its reservation headquarters for the Blackfeet Indians. The agency was only here for about 7 years but this spot was where the first white-administered schools for Blackfeet children began, in 1872.

The federal imprint has lingered on this land for almost 150 years. Today north of Choteau this highway historical marker, and a lonely boulder set square in the adjacent field, mark the first federal intrusion, the creation of the Teton River Agency, where in 1868-69 the federal government established its reservation headquarters for the Blackfeet Indians. The agency was only here for about 7 years but this spot was where the first white-administered schools for Blackfeet children began, in 1872. Irrigation systems would be a third federal imprint on the landscape and it came early to this region–through the Reclamation Service’s Valier Irrigation Project–but to find that place you need to venture a bit east of U.S. 89 to the town of Valier, on the banks of Lake Frances, which was created as a reservoir for the irrigation project.

Irrigation systems would be a third federal imprint on the landscape and it came early to this region–through the Reclamation Service’s Valier Irrigation Project–but to find that place you need to venture a bit east of U.S. 89 to the town of Valier, on the banks of Lake Frances, which was created as a reservoir for the irrigation project. Valier has never been a very big place, but its investors in 1908, including William S. Cargill of the powerful Cargill family of Wisconsin (today’s Cargill Industries), had high hopes that the engineered landscape could create a ranching and farming wonderland.

Valier has never been a very big place, but its investors in 1908, including William S. Cargill of the powerful Cargill family of Wisconsin (today’s Cargill Industries), had high hopes that the engineered landscape could create a ranching and farming wonderland.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the school remains in use today, as a bed and breakfast establishment. Even though Valier never reached the dreams of the Cargills and other outside investors, it has been a stable agricultural community for 100 years–the population today is only 100 less than what the census takers marked in 1920. Valier has that

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the school remains in use today, as a bed and breakfast establishment. Even though Valier never reached the dreams of the Cargills and other outside investors, it has been a stable agricultural community for 100 years–the population today is only 100 less than what the census takers marked in 1920. Valier has that

Heritage tourism also remains alive along U.S. Highway 89, and for those travelers who slow just a bit there is now the Two Medicine Dinosaur Center at Bynum.

Heritage tourism also remains alive along U.S. Highway 89, and for those travelers who slow just a bit there is now the Two Medicine Dinosaur Center at Bynum.

We just finished an exploration of U.S. Highway south from Great Falls to Livingston, the gateway to Yellowstone National Park. Now let’s head in the opposite direction, north of Great Falls to Glacier National Park. In the first half of this trek, one great man-made landscape dominates either side of the road–the Sun River Irrigation Project, established by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 1906 but not completed until the late 1920s.

We just finished an exploration of U.S. Highway south from Great Falls to Livingston, the gateway to Yellowstone National Park. Now let’s head in the opposite direction, north of Great Falls to Glacier National Park. In the first half of this trek, one great man-made landscape dominates either side of the road–the Sun River Irrigation Project, established by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 1906 but not completed until the late 1920s.

Feeding in and out of Fairfield are multiple canals and ditches, with the great bulk of land devoted to the production of malting barley, under

Feeding in and out of Fairfield are multiple canals and ditches, with the great bulk of land devoted to the production of malting barley, under

Fairfield itself is a classic T-plan railroad town. The barley granaries dominate the trackside, where also is located the headquarters for the Greenfields Irrigation District, so designated in 1926.

Fairfield itself is a classic T-plan railroad town. The barley granaries dominate the trackside, where also is located the headquarters for the Greenfields Irrigation District, so designated in 1926. Along the stem of the “T” plan are all of the primary commercial buildings of the town, from an unassuming log visitor center to various one-story commercial buildings, and, naturally, a classic bar, the Silver Dollar.

Along the stem of the “T” plan are all of the primary commercial buildings of the town, from an unassuming log visitor center to various one-story commercial buildings, and, naturally, a classic bar, the Silver Dollar.

Public spaces and institutions are located at the bottom of the “T,” including a community park and swimming pool, a c. 1960 community hall, and an Art-Deco styled Fairfield High School. The park, pool, and high school were all part of the second period of federal improvement at Fairfield during the New Deal era.

Public spaces and institutions are located at the bottom of the “T,” including a community park and swimming pool, a c. 1960 community hall, and an Art-Deco styled Fairfield High School. The park, pool, and high school were all part of the second period of federal improvement at Fairfield during the New Deal era.

Livingston was one of the Northern Pacific Railroad’s most important division points. Not only did the massive and architecturally ornate passenger station, discussed in the previous blog, serve as a gateway to Yellowstone National Park, it contained various company offices, serving as a nerve center for the thousands of miles of railroad line. If you do the typical tourist thing in Livingston, you pay attention to the depot and the many late 19th and early 20th century buildings south of the tracks.

Livingston was one of the Northern Pacific Railroad’s most important division points. Not only did the massive and architecturally ornate passenger station, discussed in the previous blog, serve as a gateway to Yellowstone National Park, it contained various company offices, serving as a nerve center for the thousands of miles of railroad line. If you do the typical tourist thing in Livingston, you pay attention to the depot and the many late 19th and early 20th century buildings south of the tracks. But to find where the real work of the railroad took place, you have to locate the underpass that takes you to the north side of the tracks, and the extensive Northern Pacific railroad shops. This area is not as busy as it once was, but enough buildings remain and enough activity takes place 24-7 that you quickly grasp that here is the heartbeat of the line. In the photo above, one early shop building, the lighter color brick building to the right center, still stands. Most others date to the line’s diesel conversion in the mid-20th century.

But to find where the real work of the railroad took place, you have to locate the underpass that takes you to the north side of the tracks, and the extensive Northern Pacific railroad shops. This area is not as busy as it once was, but enough buildings remain and enough activity takes place 24-7 that you quickly grasp that here is the heartbeat of the line. In the photo above, one early shop building, the lighter color brick building to the right center, still stands. Most others date to the line’s diesel conversion in the mid-20th century. With the mountains to the south, and the outlines of the town visible as well, the shops are impressive statements of corporate power and determination, and how railroads gave an industrial cast to the landscape.

With the mountains to the south, and the outlines of the town visible as well, the shops are impressive statements of corporate power and determination, and how railroads gave an industrial cast to the landscape. The north side, in many ways, was a separate world. Here the homes may date to the Victorian era too, but they are not the stylish period interpretations found in numbers on the south side. Rather they are vernacular styled cottages, or unadorned homes typical of America’s turn-of-the-century working class.

The north side, in many ways, was a separate world. Here the homes may date to the Victorian era too, but they are not the stylish period interpretations found in numbers on the south side. Rather they are vernacular styled cottages, or unadorned homes typical of America’s turn-of-the-century working class.

The school was converted into a community museum some 30 years ago, and if you visit the grand passenger station, you also need to stop at the school, to get a fuller picture of Livingston, the railroad town.

The school was converted into a community museum some 30 years ago, and if you visit the grand passenger station, you also need to stop at the school, to get a fuller picture of Livingston, the railroad town.

The above block of commercial businesses was once better known as the Montana Hotel while the block below, called the Hiatt Hotel in more recent years, was the Park Hotel, opened in 1904 to take advantage of increased tourist business due to the new Northern Pacific depot. Noted Montana architect C.S. Haire was the designer.

The above block of commercial businesses was once better known as the Montana Hotel while the block below, called the Hiatt Hotel in more recent years, was the Park Hotel, opened in 1904 to take advantage of increased tourist business due to the new Northern Pacific depot. Noted Montana architect C.S. Haire was the designer. These buildings served tourists in the summer months but throughout the years they relied on the “drummer” trade. Drummers were a word used to describe traveling businessmen, who rode the rails constantly, stopping at towns large and small, to drum up business for their companies. They too, like the machine shop workers on the south side, were a constant presence on the railroad lines of 100 years ago, and helped to make the lines hum with their travel and their stories.

These buildings served tourists in the summer months but throughout the years they relied on the “drummer” trade. Drummers were a word used to describe traveling businessmen, who rode the rails constantly, stopping at towns large and small, to drum up business for their companies. They too, like the machine shop workers on the south side, were a constant presence on the railroad lines of 100 years ago, and helped to make the lines hum with their travel and their stories.