Monida, at the Idaho-Montana border, on Interstate I-15.

Country towns of Beaverhead County–wait, you cry out: isn’t every town in Beaverhead County a country town? Well yes, since Dillon, the county seat, has a single stop light, you can say that. But Dillon is very much an urban oasis compared to the county’s tiny villages and towns scattered all about Beaverhead’s 5,572 square miles, making it the largest county in Montana.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

The next town north on the corridor created by the railroad/highway/interstate is Lima,  which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

Lima is a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, the plan favored by the engineers of the Utah and Northern as the railroad moved into Montana. The west side of the tracks, where the two-lane U.S. Highway 91 passed, was the primary commercial district, with several brick and frame two-story buildings ranging from the 1880s to the 1910s.

The east side, opposite old U.S. Highway 91, was a secondary area; the Lima Historical Society is trying to keep an old 1880s building intact for the 21st century.

The town’s comparative vitality is shown by its metal Butler Building-like municipal building, and historic churches, ranging from a early 20th century shingle style to a 1960s contemporary style Gothic church of the Latter Day Saints.

The town’s pride naturally is its school, which developed from the early 20th century two-story brick schoolhouse to become the town’s center of community.

Eight miles to the north is a very different historic schoolhouse, the one-story brick Dell school (1903), which had been converted into a wonderful cafe when I stopped in 1984. It is still a great place–if you don’t stop here for pie or a caramel roll (or both), you goofed.

The Calf-A is not the only place worth a look at Dell, a tiny railroad town along the historic Utah and Northern line, with the Tendroy Mountains in the background. Dell still has its

post office, within its one store, its community hall, and a good steakhouse dive, the false-front Stockyard Inn. But most importantly, for an understanding of the impact of World

War II on Montana, Dell has an air-strip, which still contains its 1940s B-17 Radar base, complete with storehouse–marked by the orange band around the building–and radar tower. Kate Hampton of the Montana State Historic Preservation Office in 2012 told me to be of the lookout for these properties. Once found throughout Montana, and part of the guidance system sending planes northward, many have disappeared over the years. Let’s hope the installation at Dell remains for sometime to come.

There are no more towns between Dell and Dillon but about halfway there is the Clark Canyon Reservoir, part of the reshaping of the northwest landscape by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in the 1960s. The bureau in 1961-1964 built the earthen dam and created the

reservoir, which inundated the small railroad town of Armstead, and led to the re-routing of U.S. Highway 91 (now incorporated into the interstate at this point).

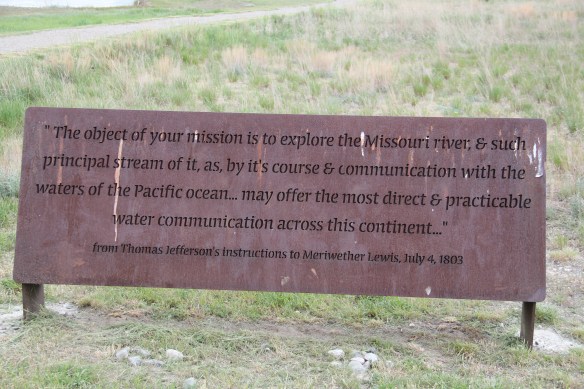

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

effort to mark and interpret the site came from the Daughters of the American Revolution, who not surprisingly focused on the Sacajawea story. Reclamation officials added other markers after the construction of the dam and reservoir.

In this century the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail has added yet another layer of public interpretation in its attempt to tell the whole story of the expedition and its complicated relations with the Native Americans of the region.

North of Dillon along the old route of U.S. Highway 91 and overlooking the corridor of the Utah and Northern Railroad is another significant Lewis and Clark site, known as Clark’s Lookout, which was opened to the public during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial of the early 21st century.

The lookout is one of the exciting historic sites that have been established in Montana in the 30 years since my initial survey for the state historic preservation plan. Not only does the property interpret an important moment in the expedition’s history–from this vantage point William Clark tried to understand the countryside before him and the best direction to take–it also allows visitors to literally walk in his footsteps and imagine the same perspective.

Of course what Clark viewed, and what you might see, are vastly different–the tracks of the Utah and Northern, then route of old U.S. 91 are right up front, while the town of Dillon creeps northward toward the lookout.

Our last stop for part one of Beaverhead’s country towns is Glen, a village best accessed by old U. S. Highway 91. A tiny post office marks the old town. Not far away are two historic

North of Glen you cross the river along old U.S. Highway 91 and encounter a great steel tress bridge, a reminder of the nature of travel along the federal highways of the mid-20th century.

I am speaking instead of the wide range of images and themes that visually interpret the town’s and county’s history. Finding public art murals about the open landscape once dominated by the Blackfeet Indians and the buffalo is not surprising–communities often embrace the deep history of their land.

I am speaking instead of the wide range of images and themes that visually interpret the town’s and county’s history. Finding public art murals about the open landscape once dominated by the Blackfeet Indians and the buffalo is not surprising–communities often embrace the deep history of their land. That Cut Bank also has a large expressive mural about the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not surprising–murals about Lewis and Clark were installed across several towns during the bicentennial of the expedition in the first decade of this century. East of Cut Bank is Camp Disappointment, one of the more important sites associated with the Corps of Discovery.

That Cut Bank also has a large expressive mural about the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not surprising–murals about Lewis and Clark were installed across several towns during the bicentennial of the expedition in the first decade of this century. East of Cut Bank is Camp Disappointment, one of the more important sites associated with the Corps of Discovery. Nor is it surprising to see communities commemorate their homesteading roots, and the importance of agriculture and cattle ranching.

Nor is it surprising to see communities commemorate their homesteading roots, and the importance of agriculture and cattle ranching.

But I was surprised, pleasantly, by the number of murals that also documented the town’s twentieth century history, whether it is the magnificent steel trestle of the Great Northern Railway just west of the commercial core, or a mural that reminded everyone of the days when the railroad dominated all traffic here.

But I was surprised, pleasantly, by the number of murals that also documented the town’s twentieth century history, whether it is the magnificent steel trestle of the Great Northern Railway just west of the commercial core, or a mural that reminded everyone of the days when the railroad dominated all traffic here.

It is this first half of the 20th century feel that the murals interpret–the era that actually built most of the historic buildings you find there today–that I find so impressive and memorable about Cut Bank, be it people on bicycles or what an old service station was like.

It is this first half of the 20th century feel that the murals interpret–the era that actually built most of the historic buildings you find there today–that I find so impressive and memorable about Cut Bank, be it people on bicycles or what an old service station was like.

Space matters when you interpret the built environment, and these various murals reflect not only a sense of town pride and identity they also give meaning to buildings and stories long forgotten.

Space matters when you interpret the built environment, and these various murals reflect not only a sense of town pride and identity they also give meaning to buildings and stories long forgotten.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83. But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana.

But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana. In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s.

In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s. Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana.

Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana. Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers.

Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers. The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex.

The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex. The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole. There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.

There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley.

Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley. At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93. And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

And the coffee is always hot, and strong. Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area. Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

Montana Highway 41 and the western side of the county is where I start, with the town of Silver Star, nestled between a spur line of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Highway 41, and Jefferson River. Gold was discovered nearby in 1866 and the town is named for a mine, but growth came more from transportation, with Silver Star serving as an early transportation stop between Virginia City and Helena in the 1870s. Today the place is best known for a privately held massive collection of mining machines, tools, and artifacts established by Lloyd Harkins, and for its rural post office that is nestled within the town’s general store.

Montana Highway 41 and the western side of the county is where I start, with the town of Silver Star, nestled between a spur line of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Highway 41, and Jefferson River. Gold was discovered nearby in 1866 and the town is named for a mine, but growth came more from transportation, with Silver Star serving as an early transportation stop between Virginia City and Helena in the 1870s. Today the place is best known for a privately held massive collection of mining machines, tools, and artifacts established by Lloyd Harkins, and for its rural post office that is nestled within the town’s general store.

valley and its irrigation systems helped to produce one of the most famous barns in the state: the Round Barn, just north of Twin Bridges. In 1882 Noah Armstrong, who had made a fortune in mining, built the barn as part of his Doncaster Stable and Stud Farm. In 1933

valley and its irrigation systems helped to produce one of the most famous barns in the state: the Round Barn, just north of Twin Bridges. In 1882 Noah Armstrong, who had made a fortune in mining, built the barn as part of his Doncaster Stable and Stud Farm. In 1933 the Bayers family acquired the barn and incorporated it into their cattle business. When I visited in 1912 the barn was still an agricultural structure, with its wedding cake shape casting a distinct profile on the landscape. In 2015, the barn was restored to a new use: as a wedding and event reception space.

the Bayers family acquired the barn and incorporated it into their cattle business. When I visited in 1912 the barn was still an agricultural structure, with its wedding cake shape casting a distinct profile on the landscape. In 2015, the barn was restored to a new use: as a wedding and event reception space.

The result is spectacular, and with their restoration in the last 30 years, the buildings are not just landmarks but busy throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

The result is spectacular, and with their restoration in the last 30 years, the buildings are not just landmarks but busy throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

The Old Hotel, a brick two-story gable-front building, also marks the town’s ascent during the early 20th century when the town achieved its highest population, about 750 in 1920. Today about half of that number call Twin Bridges home.

The Old Hotel, a brick two-story gable-front building, also marks the town’s ascent during the early 20th century when the town achieved its highest population, about 750 in 1920. Today about half of that number call Twin Bridges home. My personal favorite, and a frequent stop during the 1980s, is the Blue Anchor Bar, nestled on the first floor, with an Art Deco style redesign, in a two-story commercial block.

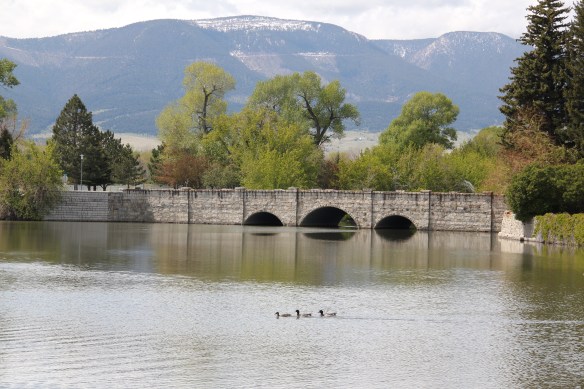

My personal favorite, and a frequent stop during the 1980s, is the Blue Anchor Bar, nestled on the first floor, with an Art Deco style redesign, in a two-story commercial block. Twin Bridges is a very important river junction, thus the name, where the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Ruby rivers all meet to form the Jefferson River. A public park near the confluence just south of the Montana 41/287 helps to tell that story. Nearby is the Twin Bridges School and its amazing modernist styled gymnasium.

Twin Bridges is a very important river junction, thus the name, where the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Ruby rivers all meet to form the Jefferson River. A public park near the confluence just south of the Montana 41/287 helps to tell that story. Nearby is the Twin Bridges School and its amazing modernist styled gymnasium.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks. The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention.

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention. Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community. Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

The Missouri River runs through Cascade County and is at the heart of any future Great Falls Heritage Area. This section of the river, and the portage around its falls that fueled its later nationally significant industrial development, is of course central to the story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1803-1806. The Lewis and Clark story was recognized when I surveyed Cascade County 30 years ago–the Giant Springs State Park was the primary public interpretation available then. But today the Lewis and Clark story has taken a larger part of the public history narrative in Cascade County. In 2003 the nation, state, and city kicked off the bicentennial of the expedition and that key anniversary date spurred the

The Missouri River runs through Cascade County and is at the heart of any future Great Falls Heritage Area. This section of the river, and the portage around its falls that fueled its later nationally significant industrial development, is of course central to the story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1803-1806. The Lewis and Clark story was recognized when I surveyed Cascade County 30 years ago–the Giant Springs State Park was the primary public interpretation available then. But today the Lewis and Clark story has taken a larger part of the public history narrative in Cascade County. In 2003 the nation, state, and city kicked off the bicentennial of the expedition and that key anniversary date spurred the

Despite federal budget challenges, the new interpretive center was exactly what the state needed to move forward the story of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and its many levels of impact of the peoples and landscape of the region. The center emphasized the harrowing, challenging story of the portage around the natural falls of what became Great Falls but its

Despite federal budget challenges, the new interpretive center was exactly what the state needed to move forward the story of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and its many levels of impact of the peoples and landscape of the region. The center emphasized the harrowing, challenging story of the portage around the natural falls of what became Great Falls but its exhibits and programs have significantly broadened our historical understanding of the expedition, especially its relationship with and impact on various Native American tribes from Missouri to Washington.

exhibits and programs have significantly broadened our historical understanding of the expedition, especially its relationship with and impact on various Native American tribes from Missouri to Washington. The contribution of the interpretive center to a greater local and in-state appreciation of the portage route cannot be underplayed. In the preservation survey of 1984, no one emphasized it nor pushed it as an important resource. When threats of development came about in last decade, though, determined voices from preservationists and residents helped to keep the portage route, a National Historic Landmark itself, from insensitive impacts.

The contribution of the interpretive center to a greater local and in-state appreciation of the portage route cannot be underplayed. In the preservation survey of 1984, no one emphasized it nor pushed it as an important resource. When threats of development came about in last decade, though, determined voices from preservationists and residents helped to keep the portage route, a National Historic Landmark itself, from insensitive impacts.

late 1850s. Hundreds pass by the monument near the civic center in the heart of Great Falls but this story is another national one that needs more attention, and soon than later.

late 1850s. Hundreds pass by the monument near the civic center in the heart of Great Falls but this story is another national one that needs more attention, and soon than later.