U.S. Highway 2 east of Kalispell has grown into a four-lane highway (mostly–topography thus far has kept it as a two-lane stretch west of Hungry Horse) designed to move travelers back and forth from Kalispell to Glacier National Park. In my 1984-85 state historic preservation plan work, I thought of Columbia Falls, Hungry Horse, and Martin

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

There is much more than the highway to Columbia Falls, as the three building blocks above indicate, not to mention the lead image of this blog, the town’s Masonic Lodge which has been turned into one huge public art mural about the town’s history as well as its surrounding landscape. Go to the red brick Bandit’s Bar above, and you soon discover that Columbia Falls has a good sense of itself, and even confidence that it can survive new challenges as its population has soared by over 2,000 residents since the 1980s, totaling over 5,000 today.

Once solely dependent on the Montana Veterans’ Home (1896), which is now a historic district, and then relying on the Weyerhaeuser sawmill for year round employment, Columbia Falls faces a different future now once the mill closed in the summer of 2016, taking away 200 jobs. As the historic business buildings above indicate, historic preservation could be part of that future, as the downtown’s mix of classic Western Commercial blocks mesh with modern takes on Rustic and Contemporary design and are complemented, in turn, by historic churches and the Art Deco-influenced school.

Once you leave the highway, in other words, real jewels of turn of the 20th century to mid-20th century design are in the offing. In 1984–I never looked that deep.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

Here I am thinking primarily of the contemporary design of the Visitors Center–its stone facade suggesting its connection to the now covered river bluffs but the openness of its interior conveying the ideas of space associated with 1950s design.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

Martin City is just enough off of U.S. Highway 2–it is situated more on the historic Great Northern Railroad corridor–to miss out on the gateway boom of the last 30 years, although with both the Southfork Saloon and the Deer Lick Saloon it retains its old reputation as a rough-edged place for locals.

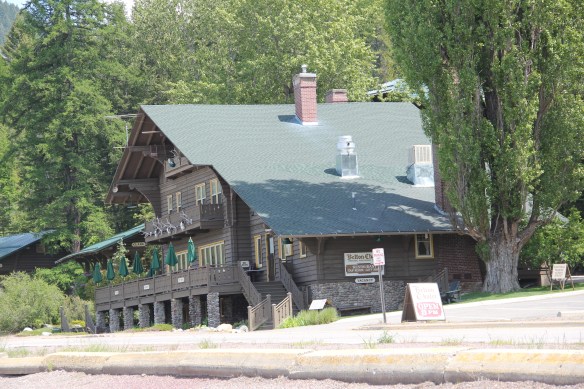

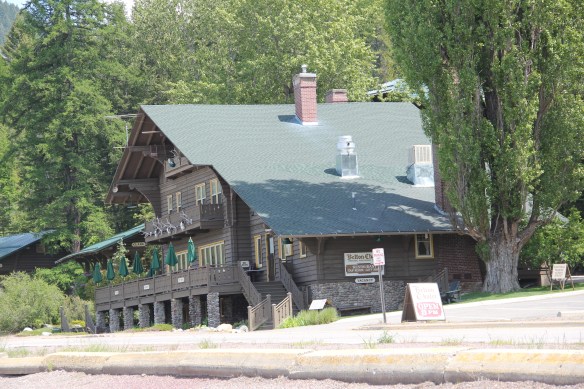

For railroad travelers in the first half of the 20th century, West Glacier was THE west gateway into Glacier National Park. The Great Northern Railway developed both the classic Rustic-styled passenger station and the adjacent Arts and Crafts/Chalet styled Belton Chalet Hotel in 1909-1910, a year before Congress created Glacier National Park.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

The Cutter buildings for the railroad between 1909-1913 set a design standard for West Glacier to follow, be it through a modern-day visitor center and a post office to the earlier mid-20th century era of the local school and then gas stations and general stores for tourists entering the national park by automobile.

This blog has never hidden the fact, however, that my favorite Glacier gateway in Flathead County is miles to the east along U.S. Highway 2 at the old railroad town of Essex, where the railroad still maintains facilities to help push freight trains over the Continental Divide. The Izaak Walton Inn was one of the first National Register assignments given to

me by State Historic Preservation Officer Marcella Sherfy–find the facts, she asked, to show that this three story bunk house, railroad offices, and local post merited exceptional significance for the National Register. Luckily I did find those facts and shaped that argument–the owners then converted a forgotten building into a memorable historical experience. Rarely do I miss a chance to spend even a few minutes here, to watch and hear the noise of the passing trains coming from the east or from the west and to catch a sunset high in the mountains of Flathead County.

The county library, above, is small but busy, a reminder of how important these public buildings can be. About 5 years ago, the time of my last visit, Scobey still had its own medical center, below, as well as a distinctive post office, different from many in the region due to its modernist style.

The county library, above, is small but busy, a reminder of how important these public buildings can be. About 5 years ago, the time of my last visit, Scobey still had its own medical center, below, as well as a distinctive post office, different from many in the region due to its modernist style.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country. I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century. Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered. The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire. The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects.

The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects. The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena.

The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena. Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.

Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.  The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings.

The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings. While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959.

While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959. It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day.

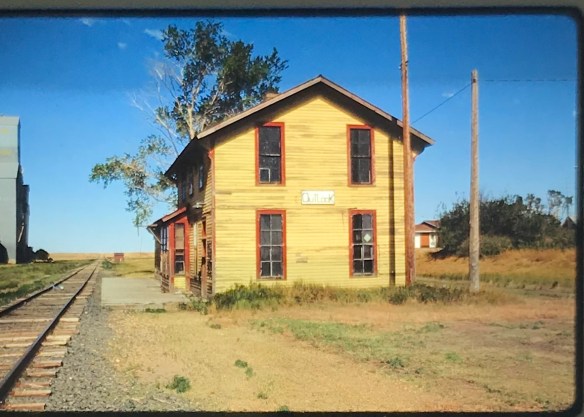

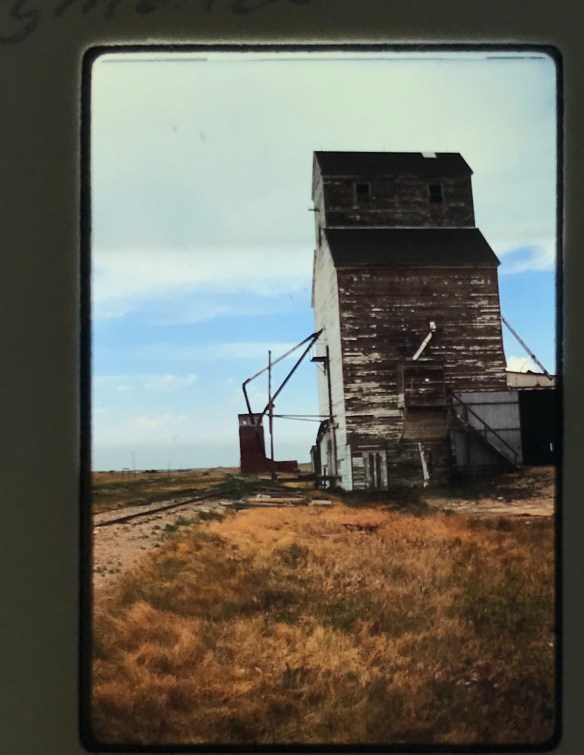

It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day. At first glance, Dutton is like many northern plains railroad towns, located on the Great Northern Railway spur line between Shelby and Great Falls. The false front of Mike’s Tavern, then other plain, functional one-story buildings–we have seen hundreds of similar scenes across the Big Sky Country.

At first glance, Dutton is like many northern plains railroad towns, located on the Great Northern Railway spur line between Shelby and Great Falls. The false front of Mike’s Tavern, then other plain, functional one-story buildings–we have seen hundreds of similar scenes across the Big Sky Country. Then, suddenly, there is the cool mid-century modernism of the Dutton-Brady School (Brady is another neighboring railroad town), a style also embraced by the Bethany Lutheran Church.

Then, suddenly, there is the cool mid-century modernism of the Dutton-Brady School (Brady is another neighboring railroad town), a style also embraced by the Bethany Lutheran Church.

Somehow it is most appropriate that my 300th post for Revisiting the Montana Landscape would find me back at Glacier National Park, especially the west side or Flathead County part of the park. From the first visit in 1982, Glacier always intrigued me–at first because of the tie between park creation and railroad development, then the Arts and Crafts/Chalet architecture associated with the park, and then high mountain Alpine environment. In the years since, I have eagerly grabbed a chance to get a cabin by Lake McDonald and just re-charge for a few days.

Somehow it is most appropriate that my 300th post for Revisiting the Montana Landscape would find me back at Glacier National Park, especially the west side or Flathead County part of the park. From the first visit in 1982, Glacier always intrigued me–at first because of the tie between park creation and railroad development, then the Arts and Crafts/Chalet architecture associated with the park, and then high mountain Alpine environment. In the years since, I have eagerly grabbed a chance to get a cabin by Lake McDonald and just re-charge for a few days. For the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work, however, I did not visit the west side of the park–the bulk of the travel took place between mid-February to mid-May 1984, meaning only the lower elevations such as Apgar Village were accessible. But already the state historic preservation office was aware that a major effort was underway to identify and nominate key properties within the park to the National Register of Historic Places, and by the end of the decade that process was largely complete. The National Park Service identified a range of historic resources from the turn of the 20th century to the Mission 66 program of the National Park Service during the 1960s–Glacier became one of the best studied historic landscapes in all of Montana.

For the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work, however, I did not visit the west side of the park–the bulk of the travel took place between mid-February to mid-May 1984, meaning only the lower elevations such as Apgar Village were accessible. But already the state historic preservation office was aware that a major effort was underway to identify and nominate key properties within the park to the National Register of Historic Places, and by the end of the decade that process was largely complete. The National Park Service identified a range of historic resources from the turn of the 20th century to the Mission 66 program of the National Park Service during the 1960s–Glacier became one of the best studied historic landscapes in all of Montana.

Register as an excellent example of Mission 66-associated architecture within the park. Burt L. Gewalt of the Kalispell firm Brinkman and Lenon was the architect.

Register as an excellent example of Mission 66-associated architecture within the park. Burt L. Gewalt of the Kalispell firm Brinkman and Lenon was the architect. Great Northern officials considered the lodge to be the center of the mountain experience on the park’s west side. From there visitors could take overnight hikes to two other facilities, shown below, the Granite Park Chalet to the northeast or the Sperry Chalet to the southeast of Lake McDonald, both of which are also listed in the National Register.

Great Northern officials considered the lodge to be the center of the mountain experience on the park’s west side. From there visitors could take overnight hikes to two other facilities, shown below, the Granite Park Chalet to the northeast or the Sperry Chalet to the southeast of Lake McDonald, both of which are also listed in the National Register.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

“lone eagles” was local–an attempt to describe those professionals “who fly to work as comfortably as most Americans drive, and whose use of computers in business lets them indulge their preference for life in the great outdoors,” as a June 19, 1994 story in the New York Times explained.

“lone eagles” was local–an attempt to describe those professionals “who fly to work as comfortably as most Americans drive, and whose use of computers in business lets them indulge their preference for life in the great outdoors,” as a June 19, 1994 story in the New York Times explained.

The station along with the railroad tracks defined everything you saw in Whitefish–here in the classic Great Northern T-plan landscape was a classic railroad town–one that old-timers even called the best along the entire line. Whitefish developed and then prospered as a division point on the mainline from 1904 to 1955–and that corporate imprint was still there to be experienced, in 1984.

The station along with the railroad tracks defined everything you saw in Whitefish–here in the classic Great Northern T-plan landscape was a classic railroad town–one that old-timers even called the best along the entire line. Whitefish developed and then prospered as a division point on the mainline from 1904 to 1955–and that corporate imprint was still there to be experienced, in 1984. Thankfully in 2015, I still found all of my favorite landmarks from 30 years earlier, even though there was little doubt that the business district had been altered, sometimes in ways that left little original fabric in place but still some two-story brick blocks stood.

Thankfully in 2015, I still found all of my favorite landmarks from 30 years earlier, even though there was little doubt that the business district had been altered, sometimes in ways that left little original fabric in place but still some two-story brick blocks stood.

A much earlier landmark, the Classical Revival Masonic Temple from the town’s first decade still stood, and it too found a new use through adaptive reuse.

A much earlier landmark, the Classical Revival Masonic Temple from the town’s first decade still stood, and it too found a new use through adaptive reuse. Despite the population boom over the last 30 years, Whitefish still uses its Art Deco-styled school from the New Deal decade of the 1930s, although the auditorium has been restored and updated into a community performing arts center.

Despite the population boom over the last 30 years, Whitefish still uses its Art Deco-styled school from the New Deal decade of the 1930s, although the auditorium has been restored and updated into a community performing arts center.

The images above and those below come from those well maintained neighborhoods, where the sense of place and pride is so strongly stated.

The images above and those below come from those well maintained neighborhoods, where the sense of place and pride is so strongly stated.