Montana Highway 200 follows the Blackfoot River as it enters Missoula County from the east. At first you think here is another rural mountain county in Montana, one still defined by community schools like the turn of the century one at Potomac above, and by community halls like the Potomac/Greenough Hall, which also serves as the local Grange meeting place.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83.

But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana.

But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana.

In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s.

In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s.

Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana.

Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana.

Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers.

Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers.

The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex.

The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex.

The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

The industrial company town of Bonner is a fascinating place to visit. On the south side side is company housing, a company store (now a museum and post office), and then other community institutions such as the Bonner School, St. Ann’s Catholic Church, and Lutheran Church.

Bonner Museum and Post Office

St. Ann’s Catholic Church, Bonner.

Our Savior Lutheran Church, Bonner.

The north side of Montana 200 has a rich array of standardized designed industrial houses, ranging from unadorned cottages to large bungalows for company administrators, all set within a landscape canopy of large trees and open green space. The mill closed in the first decade of the 21st century but the town remains and the condition of both dwellings and green space is ample testimony to the pride of place still found in Bonner.

Milltown is not as intact as Bonner. One major change came in 1907-1908 when the Milwaukee Road built through here and then in the 1920s came U.S. Highway 10. A huge swath of Milltown was cut away when Interstate highway I-90 was built 50 years later, and once the mill closed, the remaining commercial buildings have fought to remain in business, except for that that cater to travelers at the interstate exit.

One surviving institution is Harold’s Club, which stands on the opposite side of the railroad tracks. Here is your classic early 20th century roadhouse, where you could “dine, drink, and dance” the night away after a hard day at the mills.

The closing of the mills changed life in Bonner and Milltown but it did not end it. Far from it. I found the residents proud of their past and determined to build a future out of a landscape marked by failed dams, fires, corporate abandonment, and shifting global markets.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters. The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory.

The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory. The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century.

The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century. Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history. Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses.

Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses. In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole. There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.

There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley.

Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley. At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93. And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

And the coffee is always hot, and strong. Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as

Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984.

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984. But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats!

But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats! Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers. Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

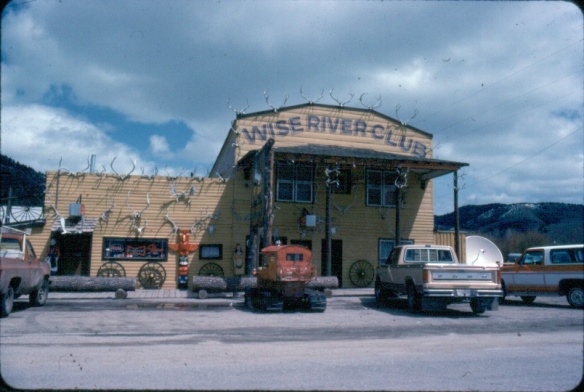

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building.

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building. But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar.

But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar. Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions.

Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions. The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse.

building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse. Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop.

Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop. But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

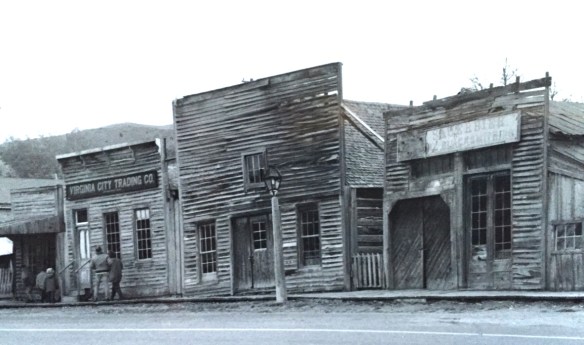

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

The two lanes of U.S. Highway 89 as it winds northwest from Choteau to the southern boundary of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, cross a stark yet compelling landscape, a jaunt that has never ceased to amaze me. To those only with the mountains of Glacier National Park in their minds will see merely open land, irrigated fields, scattered ranches.

The two lanes of U.S. Highway 89 as it winds northwest from Choteau to the southern boundary of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, cross a stark yet compelling landscape, a jaunt that has never ceased to amaze me. To those only with the mountains of Glacier National Park in their minds will see merely open land, irrigated fields, scattered ranches. But there’s a deeper landscape here, some embodied in the tiny towns along the way, others in places just ignored, certainly not recognized. In the first post of 2016, and the 200th of this series of explorations of the Montana landscape, let’s once again look a bit harder.

But there’s a deeper landscape here, some embodied in the tiny towns along the way, others in places just ignored, certainly not recognized. In the first post of 2016, and the 200th of this series of explorations of the Montana landscape, let’s once again look a bit harder. For one, this is a landscape shaped by Cold War America. Nuclear missile silos were installed throughout the region with some easily accessible from the roadway. You wonder how many tourists realize that.

For one, this is a landscape shaped by Cold War America. Nuclear missile silos were installed throughout the region with some easily accessible from the roadway. You wonder how many tourists realize that. The federal imprint has lingered on this land for almost 150 years. Today north of Choteau this highway historical marker, and a lonely boulder set square in the adjacent field, mark the first federal intrusion, the creation of the Teton River Agency, where in 1868-69 the federal government established its reservation headquarters for the Blackfeet Indians. The agency was only here for about 7 years but this spot was where the first white-administered schools for Blackfeet children began, in 1872.

The federal imprint has lingered on this land for almost 150 years. Today north of Choteau this highway historical marker, and a lonely boulder set square in the adjacent field, mark the first federal intrusion, the creation of the Teton River Agency, where in 1868-69 the federal government established its reservation headquarters for the Blackfeet Indians. The agency was only here for about 7 years but this spot was where the first white-administered schools for Blackfeet children began, in 1872. Irrigation systems would be a third federal imprint on the landscape and it came early to this region–through the Reclamation Service’s Valier Irrigation Project–but to find that place you need to venture a bit east of U.S. 89 to the town of Valier, on the banks of Lake Frances, which was created as a reservoir for the irrigation project.

Irrigation systems would be a third federal imprint on the landscape and it came early to this region–through the Reclamation Service’s Valier Irrigation Project–but to find that place you need to venture a bit east of U.S. 89 to the town of Valier, on the banks of Lake Frances, which was created as a reservoir for the irrigation project. Valier has never been a very big place, but its investors in 1908, including William S. Cargill of the powerful Cargill family of Wisconsin (today’s Cargill Industries), had high hopes that the engineered landscape could create a ranching and farming wonderland.

Valier has never been a very big place, but its investors in 1908, including William S. Cargill of the powerful Cargill family of Wisconsin (today’s Cargill Industries), had high hopes that the engineered landscape could create a ranching and farming wonderland.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the school remains in use today, as a bed and breakfast establishment. Even though Valier never reached the dreams of the Cargills and other outside investors, it has been a stable agricultural community for 100 years–the population today is only 100 less than what the census takers marked in 1920. Valier has that

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the school remains in use today, as a bed and breakfast establishment. Even though Valier never reached the dreams of the Cargills and other outside investors, it has been a stable agricultural community for 100 years–the population today is only 100 less than what the census takers marked in 1920. Valier has that

Heritage tourism also remains alive along U.S. Highway 89, and for those travelers who slow just a bit there is now the Two Medicine Dinosaur Center at Bynum.

Heritage tourism also remains alive along U.S. Highway 89, and for those travelers who slow just a bit there is now the Two Medicine Dinosaur Center at Bynum.

We just finished an exploration of U.S. Highway south from Great Falls to Livingston, the gateway to Yellowstone National Park. Now let’s head in the opposite direction, north of Great Falls to Glacier National Park. In the first half of this trek, one great man-made landscape dominates either side of the road–the Sun River Irrigation Project, established by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 1906 but not completed until the late 1920s.

We just finished an exploration of U.S. Highway south from Great Falls to Livingston, the gateway to Yellowstone National Park. Now let’s head in the opposite direction, north of Great Falls to Glacier National Park. In the first half of this trek, one great man-made landscape dominates either side of the road–the Sun River Irrigation Project, established by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 1906 but not completed until the late 1920s.

Feeding in and out of Fairfield are multiple canals and ditches, with the great bulk of land devoted to the production of malting barley, under

Feeding in and out of Fairfield are multiple canals and ditches, with the great bulk of land devoted to the production of malting barley, under

Fairfield itself is a classic T-plan railroad town. The barley granaries dominate the trackside, where also is located the headquarters for the Greenfields Irrigation District, so designated in 1926.

Fairfield itself is a classic T-plan railroad town. The barley granaries dominate the trackside, where also is located the headquarters for the Greenfields Irrigation District, so designated in 1926. Along the stem of the “T” plan are all of the primary commercial buildings of the town, from an unassuming log visitor center to various one-story commercial buildings, and, naturally, a classic bar, the Silver Dollar.

Along the stem of the “T” plan are all of the primary commercial buildings of the town, from an unassuming log visitor center to various one-story commercial buildings, and, naturally, a classic bar, the Silver Dollar.

Public spaces and institutions are located at the bottom of the “T,” including a community park and swimming pool, a c. 1960 community hall, and an Art-Deco styled Fairfield High School. The park, pool, and high school were all part of the second period of federal improvement at Fairfield during the New Deal era.

Public spaces and institutions are located at the bottom of the “T,” including a community park and swimming pool, a c. 1960 community hall, and an Art-Deco styled Fairfield High School. The park, pool, and high school were all part of the second period of federal improvement at Fairfield during the New Deal era.