Miners first began to gather at what is now Philipsburg in the late 1860s; the town was later named for Philip Deidesheimer, who operated the Bi-Metallic Mine works. As the Bi-Metallic Mine and Mill expanded operations in the 1880s, a rapid boom in building

Miners first began to gather at what is now Philipsburg in the late 1860s; the town was later named for Philip Deidesheimer, who operated the Bi-Metallic Mine works. As the Bi-Metallic Mine and Mill expanded operations in the 1880s, a rapid boom in building

occurred, creating one and two-story brick buildings with dazzling Eastlake-styled cast-iron facades. The town was incorporated in 1890.

The quality of the Victorian commercial architecture still extant in Phillipsburg, such as the 1888 Sayrs Block above, astounded me during the 1984-85 preservation work. So much was intact but so much needed help. Residents, local officials, and the state preservation office understood that and by 1986 the Philipsburg Commercial historic district had been added to the National Register of Historic Places.

The quality of the Victorian commercial architecture still extant in Phillipsburg, such as the 1888 Sayrs Block above, astounded me during the 1984-85 preservation work. So much was intact but so much needed help. Residents, local officials, and the state preservation office understood that and by 1986 the Philipsburg Commercial historic district had been added to the National Register of Historic Places.

What is exciting is that in this decade, entrepreneurs are building upon early successful renovations and adaptive reuse project to launch new businesses and create new jobs. The town’s population is growing, after 30 years of decline.

What is exciting is that in this decade, entrepreneurs are building upon early successful renovations and adaptive reuse project to launch new businesses and create new jobs. The town’s population is growing, after 30 years of decline.

No business has been more central to this transformation than the Sweet Palace, shown above, which is next door to the two-story brick Masonic Lodge.

Another key to recent success has the resurrection of local hotels and bed and breakfast establishments, along with the staging of various summer productions at the town’s Opera House Theatre, built in 1896, making it the longest continuous operating theater in the state. These properties give visitors a reason to stay longer, and not just stop at the Candy Store, grab a brew at one of the town’s historic bars, and then move along.

The town has recently added an amphitheater, located behind the historic school building, that also serves summer events that drive ever-increasing numbers of people to visit this mountain mining town and to spend more time and money there. This is modern-day heritage development at work.

The new developments in Philipsburg are interesting and invaluable changes since 1984-1985. At the same time, I am happy that residents have still embraced their historic public buildings in a similar fashion. The photograph I used in my book about the town in 1985

The new developments in Philipsburg are interesting and invaluable changes since 1984-1985. At the same time, I am happy that residents have still embraced their historic public buildings in a similar fashion. The photograph I used in my book about the town in 1985

was the Philipsburg School, with its soaring tower symbolizing the hopes that residents had for Philipsburg’s future in the 1890s. The historic school, which is listed in the National Register, remains although the community built a new building adjacent to the historic one in 1987. (you can see a corner of the new building at the lower left).

was the Philipsburg School, with its soaring tower symbolizing the hopes that residents had for Philipsburg’s future in the 1890s. The historic school, which is listed in the National Register, remains although the community built a new building adjacent to the historic one in 1987. (you can see a corner of the new building at the lower left).

When I first visited in 1984 the only building in Philipsburg listed in the National Register was the Queen Anne-styled Granite County Jail of 1902. It also remains in use.

When I first visited in 1984 the only building in Philipsburg listed in the National Register was the Queen Anne-styled Granite County Jail of 1902. It also remains in use.

But now the Classical Revival-styled Granite County Courthouse (1913) is also listed in the National Register. Designed by the important Montana architectural firm of Link and Haire, this small town county courthouse also speaks to the county’s early 20th century ambitions, with its stately classical columned portico and its central classical cupola.

But now the Classical Revival-styled Granite County Courthouse (1913) is also listed in the National Register. Designed by the important Montana architectural firm of Link and Haire, this small town county courthouse also speaks to the county’s early 20th century ambitions, with its stately classical columned portico and its central classical cupola.

By climbing the hill above the courthouse you also gain a great overview look of the town, reminding you that these rather imposing public buildings are within what is truly a modest urban setting that is connected to the wider world by Montana Highway 1.

By climbing the hill above the courthouse you also gain a great overview look of the town, reminding you that these rather imposing public buildings are within what is truly a modest urban setting that is connected to the wider world by Montana Highway 1.

A couple of final thoughts on Philipsburg. Its range of domestic architecture from c. 1875 to 1925 is limited in numbers but impressive in the variety of forms, from brick cottages to brick Queen Anne homes to textbook examples of bungalows and American Four Squares.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the M.E. Dow House is a frame Queen Anne home, modest considering the flamboyant Eastlake-styled cast-iron front to his downtown business block.

The Philipsburg Cemetery, which like so many that I ignored in 1984-1985, was a revelation, reflecting the quality of Victorian period architecture found in the town.

The Philipsburg Cemetery, which like so many that I ignored in 1984-1985, was a revelation, reflecting the quality of Victorian period architecture found in the town.

The beauty and serenity of its setting were impressive enough, but then some of the family plots and individual markers reflected Victorian era mortuary art at its best.

The beauty and serenity of its setting were impressive enough, but then some of the family plots and individual markers reflected Victorian era mortuary art at its best.

This cast-iron gate, completed with urns on each post and the music lyre gate, is among the most impressive I have encountered in any small town across America. And this cemetery has two separate ones.

This cast-iron gate, completed with urns on each post and the music lyre gate, is among the most impressive I have encountered in any small town across America. And this cemetery has two separate ones.

Many grave markers came from local or nearby masons but others, like these for the Schuh and Jennings families, were cast in metal, imitating stone, and shipped by railroad to Philipsburg.

Many grave markers came from local or nearby masons but others, like these for the Schuh and Jennings families, were cast in metal, imitating stone, and shipped by railroad to Philipsburg.

Other markers are not architecturally impressive but they tell stories, such as the one below, for Mr. George M. Blum, a native of Germany, who was “killed in runaway at Phillipsburg” in 1903. I look forward to a future visit to this cemetery for further research.

contemporary styling of the Ravalli County Bank or the “new” county courthouse of 1976, a building that I totally dismissed in 1984 but now that it has reached the 40 year mark the design seems so much of its time, and a very interesting local reaction by the firm of Howland and Associates to the ne0-Colonial Revival that gripped so much of the nation during the American bicentennial.

contemporary styling of the Ravalli County Bank or the “new” county courthouse of 1976, a building that I totally dismissed in 1984 but now that it has reached the 40 year mark the design seems so much of its time, and a very interesting local reaction by the firm of Howland and Associates to the ne0-Colonial Revival that gripped so much of the nation during the American bicentennial.

Adaptive reuse had put some buildings back into use, such as the historic Creamery, once such an important link between town and ranch in the county. Other landmarks didn’t

Adaptive reuse had put some buildings back into use, such as the historic Creamery, once such an important link between town and ranch in the county. Other landmarks didn’t

This birds-eye view of the town is at the Beaverhead County Museum at the railroad depot. It shows the symmetrical plan well, with two-story commercial blocks facing the tracks and depot, which was then just a frame building. To the opposite side of the tracks with more laborer cottages and one outstanding landmark, the Second Empire-style Hotel Metlen. The Metlen, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, remains today, one

This birds-eye view of the town is at the Beaverhead County Museum at the railroad depot. It shows the symmetrical plan well, with two-story commercial blocks facing the tracks and depot, which was then just a frame building. To the opposite side of the tracks with more laborer cottages and one outstanding landmark, the Second Empire-style Hotel Metlen. The Metlen, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, remains today, one of the state’s best examples of a railroad hotel. I recognized the building as such in the 1984 state historic preservation plan and my book, A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History, included the image below of the hotel.

of the state’s best examples of a railroad hotel. I recognized the building as such in the 1984 state historic preservation plan and my book, A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History, included the image below of the hotel. This three-story hotel served not only tourists but especially traveling businessmen–called drummers because they were out “drumming up” business for their companies. The interior has received some restoration work in the last 30 years but little has changed in the facade, as they two images, one from 1990 and the other from 2012, indicate.

This three-story hotel served not only tourists but especially traveling businessmen–called drummers because they were out “drumming up” business for their companies. The interior has received some restoration work in the last 30 years but little has changed in the facade, as they two images, one from 1990 and the other from 2012, indicate.

built environment has many stories to tell.

built environment has many stories to tell. Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as

Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984.

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984. But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats!

But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats! Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers. Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

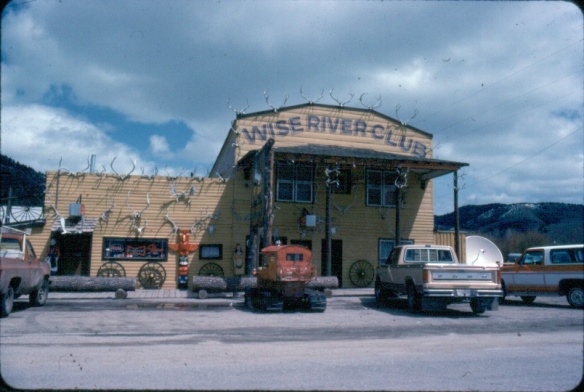

Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building.

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building. But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar.

But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar. Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions.

Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions. The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains. Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years.

Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years. The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution

The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies. I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer

I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse.

building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse. Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop.

Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop. But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

Nestled where Montana Highway 287 encounters U.S. Highway 287 in the southern end of Madison County, Ennis has changed in significant ways in the last 30 years. Its earlier dependence on automobile tourism to Yellowstone National Park has shifted into the favor of population growth and development in this portion of the county.

Nestled where Montana Highway 287 encounters U.S. Highway 287 in the southern end of Madison County, Ennis has changed in significant ways in the last 30 years. Its earlier dependence on automobile tourism to Yellowstone National Park has shifted into the favor of population growth and development in this portion of the county. The iconic Ennis Cafe, always a favorite place back in the day of the statewide work, remains, with a new false front emphasizing the wildlife and open spaces of this area. That place, along with several classic watering holes, served not only locals but the

The iconic Ennis Cafe, always a favorite place back in the day of the statewide work, remains, with a new false front emphasizing the wildlife and open spaces of this area. That place, along with several classic watering holes, served not only locals but the

of a section of the highway where you will encounter magnificent views of the Madison River Valley and open ranch lands.

of a section of the highway where you will encounter magnificent views of the Madison River Valley and open ranch lands.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

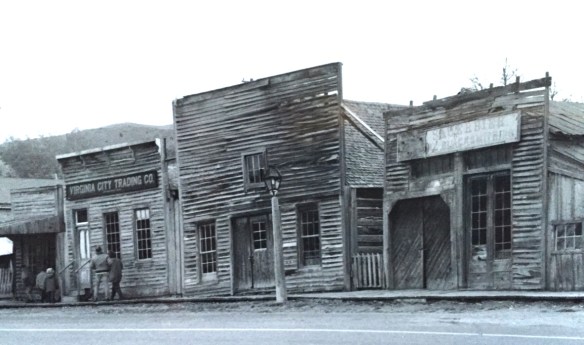

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.