Plains is the second largest town in Sanders County, noted as the home of the county fairgrounds, the center of the local agricultural economy, and like Thompson Falls a significant place along the Clark’s Fork River and the Montana Highway 200 corridor.

Plains is the second largest town in Sanders County, noted as the home of the county fairgrounds, the center of the local agricultural economy, and like Thompson Falls a significant place along the Clark’s Fork River and the Montana Highway 200 corridor.

While the population was largely the same in 2015 compared to my last visit 30 years earlier, things had changed, such as the town’s elevator now served as the Grainry Gallery–an imaginative local adaptive reuse. New churches, new homes, and new businesses had been established. Yet Plains still retained its early 20th to mid-20th

century feel, be it in institutions, such as the local Grange above, or the continuation of the local VFW hall and bowling alley, below.

century feel, be it in institutions, such as the local Grange above, or the continuation of the local VFW hall and bowling alley, below.

Among the biggest changes to this historic preservationist is the lost of the town’s historic high school from the first decade of the 20th century. In a small park along Montana Highway 200, the cornerstone arch from the school was saved and now is a

monument to that educational landmark. Adjacent is the log “Wild Horse Plains” school, which has been moved to this spot and restored during the American Bicentennial. According to local historians, the more appropriate name is “Horse Plains,” since the Salish Indians once wintered their horses here but the name “Wild Horse Plains” is the one that has stuck here in the 21st century.

The Wild Horse Plains Women’s Club uses the old school for their meetings and keeps up the property and its landscaping. Indeed, one thing you like about Plains–a railroad town from the turn of the 20th century–is its sense of pride, conveyed by places like the school park or in the stewardship shown to local historic homes.

This same pride in place is also conveyed in our last Sanders County stop, the very different history of Noxon, near the Idaho border on Montana Highway 200. The Noxon Bridge was among my favorite northwest Montana modern landmarks–but in 1984 I thought little more about it because few things in Noxon were built before 1959-60.

That was when the Noxon Hydroelectric Dam went in operation, transforming this part of the Clark’s Fork River into an engineered landscape shaped by the dam, power lines, and the reservoir.

The Noxon Dam was finished in 1959. It is a mile in length, 260 feet in height and 700 feet wide at its base. Its generators can power approximately 365,000 homes, making it the second-largest capacity hydroelectric facility in Montana.

The Noxon Dam was finished in 1959. It is a mile in length, 260 feet in height and 700 feet wide at its base. Its generators can power approximately 365,000 homes, making it the second-largest capacity hydroelectric facility in Montana.

Today visitors can view the dam from various parking areas and short walking trails, one of which passes over the historic line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The property has interpretive signs about the history of the project as well as about the engineering of hydroelectric power.

Today visitors can view the dam from various parking areas and short walking trails, one of which passes over the historic line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The property has interpretive signs about the history of the project as well as about the engineering of hydroelectric power.

Along the banks of the river/reservoir, a much more recent public park has opened–with public sculpture reminding everyone of the Native Americans who once camped along the

Along the banks of the river/reservoir, a much more recent public park has opened–with public sculpture reminding everyone of the Native Americans who once camped along the

river at this place. By bringing the deep past of the region in view of the modern, this site is a new favorite place–wherever you are in Montana, and there are many modern engineering marvels–the Indians were always there first, using those same natural resources in far different ways.

river at this place. By bringing the deep past of the region in view of the modern, this site is a new favorite place–wherever you are in Montana, and there are many modern engineering marvels–the Indians were always there first, using those same natural resources in far different ways.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road. The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

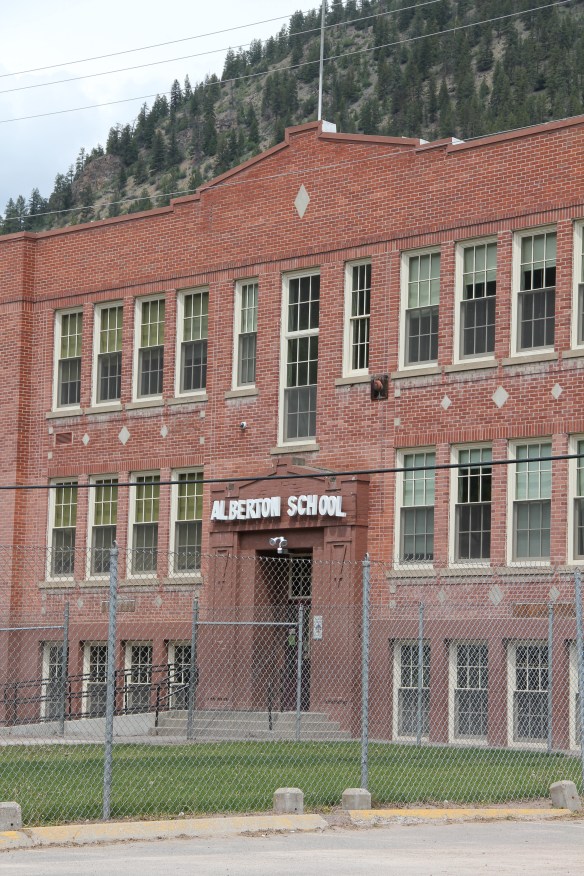

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work.

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism.

I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism. The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83. But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana.

But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana. In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s.

In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s. Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana.

Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana. Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers.

Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers. The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex.

The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex. The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters. The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory.

The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory. The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century.

The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century. Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history. Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses.

Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses. In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

Continuing west you soon encounter post-World War II service stations and motels, some updated, some much like they were, on the outskirts of town and then, boom, you are in the heart of Livingston, facing the commanding presence of the Northern Pacific depot complex with warehouses–some now converted to new uses–coming first and then

Continuing west you soon encounter post-World War II service stations and motels, some updated, some much like they were, on the outskirts of town and then, boom, you are in the heart of Livingston, facing the commanding presence of the Northern Pacific depot complex with warehouses–some now converted to new uses–coming first and then massive passenger station itself. Opened in 1902, the passenger station was an architectural marvel for the new state, designed by Reed and Stem, who would continue on to great fame as the architects of Grand Central Station in New York City. The station, interestingly, is not Classical Revival in style–certainly the choice of most architects for their grand gateways along the nation’s rail line–but a more restrained interpretation of Renaissance Revival style, completed in red brick.

massive passenger station itself. Opened in 1902, the passenger station was an architectural marvel for the new state, designed by Reed and Stem, who would continue on to great fame as the architects of Grand Central Station in New York City. The station, interestingly, is not Classical Revival in style–certainly the choice of most architects for their grand gateways along the nation’s rail line–but a more restrained interpretation of Renaissance Revival style, completed in red brick. The building is not particularly inviting for locals coming from the business district to the depot–that was not its primary audience. Rather the grand entrance is track side, where passengers headed to Yellowstone National Park could depart for food, fun, frivolity, whatever they needed before the journey into the wildness of Yellowstone.

The building is not particularly inviting for locals coming from the business district to the depot–that was not its primary audience. Rather the grand entrance is track side, where passengers headed to Yellowstone National Park could depart for food, fun, frivolity, whatever they needed before the journey into the wildness of Yellowstone.

Travelers were welcome to use the grand covered walkways to enter the depot proper, or to take a side visit to the railroad’s cafe, Martin’s as I

Travelers were welcome to use the grand covered walkways to enter the depot proper, or to take a side visit to the railroad’s cafe, Martin’s as I knew it back in the day, a place that rarely slept and always had good pie. The cafe changed its orientation from the railroad to the road as automobile travelers on U.S. 10 began to dominate the tourist market. Now it has been restored as a local brew pub.

knew it back in the day, a place that rarely slept and always had good pie. The cafe changed its orientation from the railroad to the road as automobile travelers on U.S. 10 began to dominate the tourist market. Now it has been restored as a local brew pub.

Directly facing the center of the passenger station was the mammoth Murray Hotel–a flea bag operation in the 1980s but now recently restored as a hipster place to be, especially its signature bar.

Directly facing the center of the passenger station was the mammoth Murray Hotel–a flea bag operation in the 1980s but now recently restored as a hipster place to be, especially its signature bar.

Imagine my pleasant surprise last year when I found that Gil’s still existed but now had been converted into a decidedly up-scale establishment, far removed from the 1980s.

Imagine my pleasant surprise last year when I found that Gil’s still existed but now had been converted into a decidedly up-scale establishment, far removed from the 1980s. I don’t know if I have encountered a more fundamentally changed place–cheap trinkets gone, let the wood-fired pizzas come on.

I don’t know if I have encountered a more fundamentally changed place–cheap trinkets gone, let the wood-fired pizzas come on. I was not so blinded in 1984 by the concept of the “metropolitan corridor” that I ignored the distinctive Victorian storefronts of Livingston–how could I since they all, in a way, fed into the tracks. But when I got to the end of that distinctive business district and watched the town, in my

I was not so blinded in 1984 by the concept of the “metropolitan corridor” that I ignored the distinctive Victorian storefronts of Livingston–how could I since they all, in a way, fed into the tracks. But when I got to the end of that distinctive business district and watched the town, in my mind, fade into the Rockies, I had captured the obvious but had missed the bigger picture–that’s the next story.

mind, fade into the Rockies, I had captured the obvious but had missed the bigger picture–that’s the next story. Traveling south of Clyde Park on U.S. 89, you pass by the turn-off for Horse Thief Trail, where a historic steel bridge still allows for one-lane traffic over the Shields River; this bridge and snippet of road is part of the original route of U.S 89. That means you are nearing the confluence of the Yellowstone and Shields rivers, and where U.S. Highway 89 crosses the Yellowstone River and takes you into the heart of Park County. Paralleling the modern concrete bridge is a c. 1897 steel Pratt through truss bridge, to serve the Northern Pacific Railroad spur that runs north to Clyde Park then Wilsall. The Northern Pacific called this the Third Crossing of the Yellowstone bridge; the Phoenix Bridge Company constructed it.

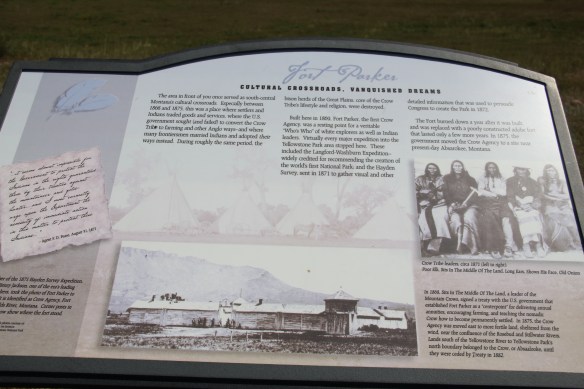

Traveling south of Clyde Park on U.S. 89, you pass by the turn-off for Horse Thief Trail, where a historic steel bridge still allows for one-lane traffic over the Shields River; this bridge and snippet of road is part of the original route of U.S 89. That means you are nearing the confluence of the Yellowstone and Shields rivers, and where U.S. Highway 89 crosses the Yellowstone River and takes you into the heart of Park County. Paralleling the modern concrete bridge is a c. 1897 steel Pratt through truss bridge, to serve the Northern Pacific Railroad spur that runs north to Clyde Park then Wilsall. The Northern Pacific called this the Third Crossing of the Yellowstone bridge; the Phoenix Bridge Company constructed it. Before jogging slightly to the west to head to Livingston, the county seat, two places east of the Shields River confluence are worth a look. First is the site of Fort Parker, established as the first Crow Agency in 1869 or the first federal facility in the valley. It operated from this location until 1875.

Before jogging slightly to the west to head to Livingston, the county seat, two places east of the Shields River confluence are worth a look. First is the site of Fort Parker, established as the first Crow Agency in 1869 or the first federal facility in the valley. It operated from this location until 1875.

Gladly all of that changed in the 21st century. As a result of another innovative state partnership with land owners, there is an interpretive center for the Fort Parker story, easily accessible from the interstate, which also does not intrude into the potentially rich archaeological remains of the fort. The story told by the historical markers is accurate and comprehensive, from the agency’s beginnings to the land today.

Gladly all of that changed in the 21st century. As a result of another innovative state partnership with land owners, there is an interpretive center for the Fort Parker story, easily accessible from the interstate, which also does not intrude into the potentially rich archaeological remains of the fort. The story told by the historical markers is accurate and comprehensive, from the agency’s beginnings to the land today.

Few remnants of that early white settlement remain today; you can find some just north of Springdale, at Park County’s eastern border, on the north side of the Yellowstone River. Hunter’s Hot Springs was the first attraction, established by Andrew Jackson Hunter in the 1870s, and receiving its last update in the early years of automobile tourism in the 1920s, as shown below in this postcard from my collection. Today, as the Google image below also shows, there are just scattered stones and fences from what had been a showplace for the valley.

Few remnants of that early white settlement remain today; you can find some just north of Springdale, at Park County’s eastern border, on the north side of the Yellowstone River. Hunter’s Hot Springs was the first attraction, established by Andrew Jackson Hunter in the 1870s, and receiving its last update in the early years of automobile tourism in the 1920s, as shown below in this postcard from my collection. Today, as the Google image below also shows, there are just scattered stones and fences from what had been a showplace for the valley.

Commercial businesses once lined the town side of the Northern Pacific tracks. Nothing is open today although trains rumbled down this historic main line every day. What does survive is impressive and worthy of

Commercial businesses once lined the town side of the Northern Pacific tracks. Nothing is open today although trains rumbled down this historic main line every day. What does survive is impressive and worthy of