In 2024 I began to see media accounts, both regionally and nationally, of how Glasgow, the seat of Valley County, was the most isolated place you can imagine, truly in the Middle of nowhere.

I’m not one to argue with geographers and economists. I’m sure from their perspective, they got it right. But I never thought of Glasgow as isolated: it is on the Great Northern mainline, and part of the famed Empire Builder Amtrak route, and on U.S. Highway 2.

Then the town has always shown a great deal of pride and ambition, conveyed so effectively by its many historic buildings, starting with the First National Bank, built c. 1884 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When you enter the town from the underpass of the railroad, the bank is the first landmark to catch your eye, appropriate too for the impact of local banks on a town’s economic prospects during the homesteading boom and bust of the 1910s and 1920s, respectively.

Another landmark from the homesteading era is the Rundle Building, once the Glasgow Hotel and restored in the last ten years as an upscale hotel in the heart of downtown. Built c. 1916 and designed by the important Billings firm of Link and Haire, the Rundle is a captivating statement of an Arts and Crafts-infused Mediterranean Revival style. I have been trying to get back to Glasgow to stay here for the last four years—maybe I will make it in 2025.

The 1930s transformed Valley County through the construction of the mammoth Fort Peck Dam on the Missouri River. Glasgow too has a major New Deal landmark in its U.S. post office and courthouse, built c. 1939 and designed by federal architect Louis A. Simon.

Its understated New Deal Deco exterior obscures a jewel of an interior, highlighted by its New Deal-funded 1942 mural depicting local history and the changes brought about by the Fort Peck Dam by artist Forest Hill. This building too is listed in the National Register.

Another important New Deal supported building was all about the community, and providing new opportunities: the Glasgow Civic Center. It too has a New Deal Deco style, and its large public space has been used for almost every type of event or gathering you can imagine.

Glasgow’s sense of itself today still respects it past, brilliantly conveyed by its large and expansive museum. When I first visited Glasgow 40 years

ago, I held a public meeting on the state historic preservation plan here, and the next morning residents gave me a detailed tour of the recently established museum. I was impressed with its collection then, now it sprawls through the building to the adjoining grounds.

Indeed, the saloon exhibit underscores another fun part of Glasgow—across from the depot in the original route of Highway 2 is an amazing collection of bars, stores, and eateries, right out of the early 1900s.

But back to the museum, and its important Montana decorative arts collection of the work of modern craftsman Thomas Molesworth, once in the town’s Carnegie library.

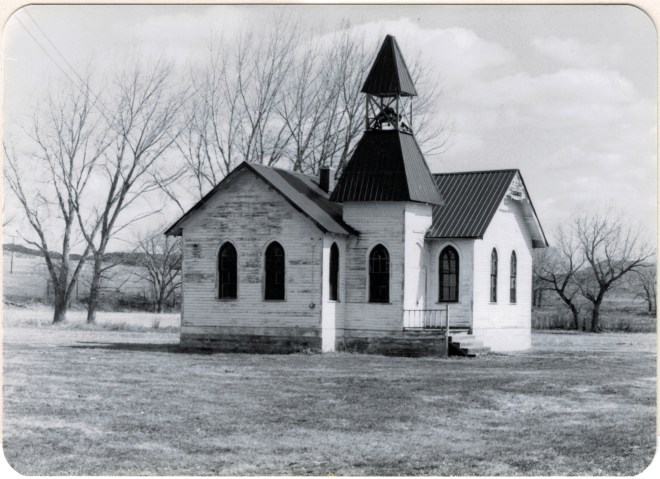

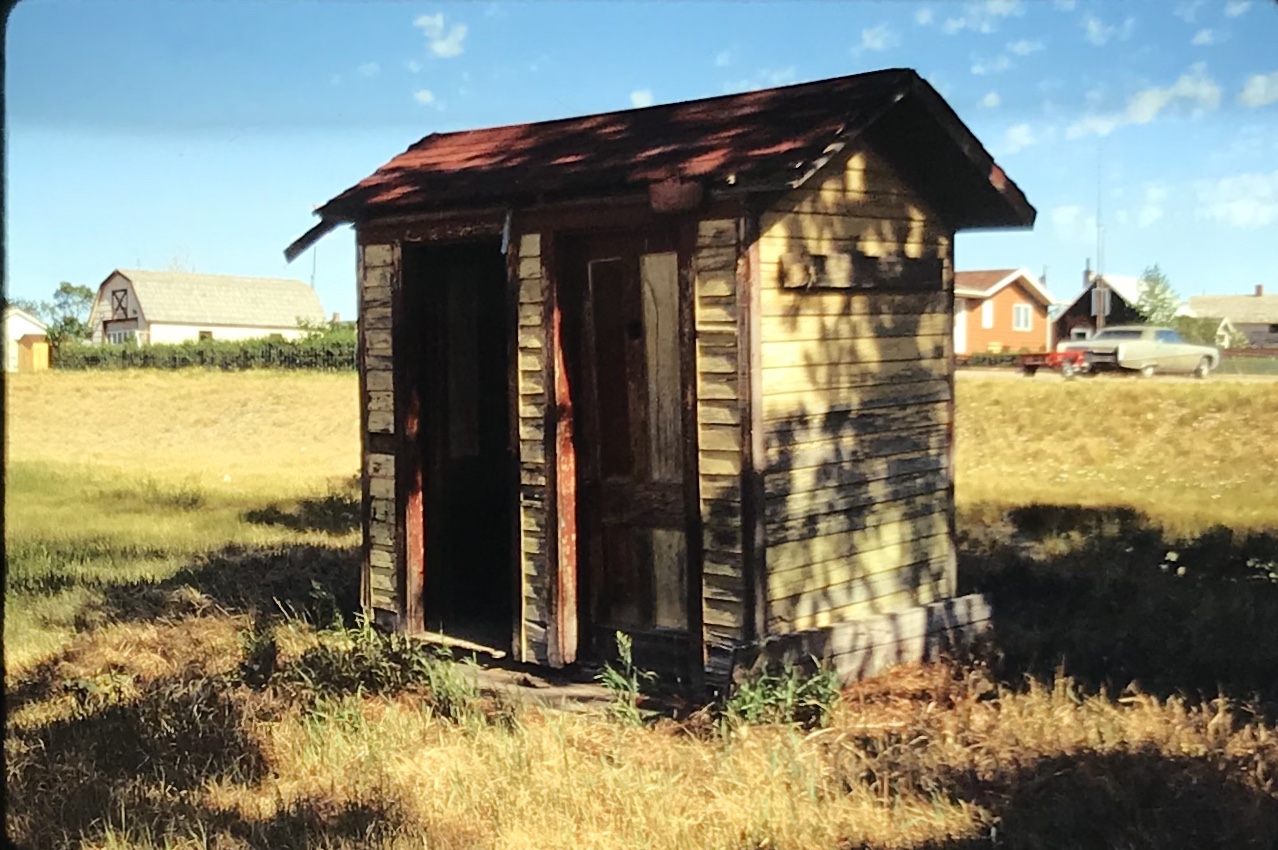

The newer exterior exhibits led the museum to move entire building to the property, including examples of the homestead shacks of the early 1900s that were followed by permanent homes such as this white painted bungalow.

Pride of place, pride of the past. Glasgow might be in the middle but it is far from being nowhere as this small sampling of properties demonstrates.

A good bit of the historic machine shops (above) still operated in 1988. The depot and railroad offices still dominated the Merrill Avenue business district (below).

A good bit of the historic machine shops (above) still operated in 1988. The depot and railroad offices still dominated the Merrill Avenue business district (below).

My favorite Merrill Avenue business was the wonderful Art Moderne style of the Luhaven Bar (below). You gots love the black carrera glass and glass block entrance.

My favorite Merrill Avenue business was the wonderful Art Moderne style of the Luhaven Bar (below). You gots love the black carrera glass and glass block entrance.

But my favorite modernist building was the First National Bank, which was later converted to the town’s public library.

But my favorite modernist building was the First National Bank, which was later converted to the town’s public library. Next posting will include homes from the town’s residential district from the early 20th century to the mid-century as I continue a look back to the Yellowstone River and its towns in 1988.

Next posting will include homes from the town’s residential district from the early 20th century to the mid-century as I continue a look back to the Yellowstone River and its towns in 1988.

But like most travelers I roar down the highway, perhaps noting the tall grain elevators facing the town proper, and pay little attention to anything else. In a post of four years ago, I spoke of Golden Valley County and its historic landmarks, highlighting the grain elevators, the Golden Valley Courthouse, the Sims-Garfield historic ranch, and the historic town bar in Ryegate. But like the other eastern Montana county seats, Ryegate deserves a closer look.

But like most travelers I roar down the highway, perhaps noting the tall grain elevators facing the town proper, and pay little attention to anything else. In a post of four years ago, I spoke of Golden Valley County and its historic landmarks, highlighting the grain elevators, the Golden Valley Courthouse, the Sims-Garfield historic ranch, and the historic town bar in Ryegate. But like the other eastern Montana county seats, Ryegate deserves a closer look.

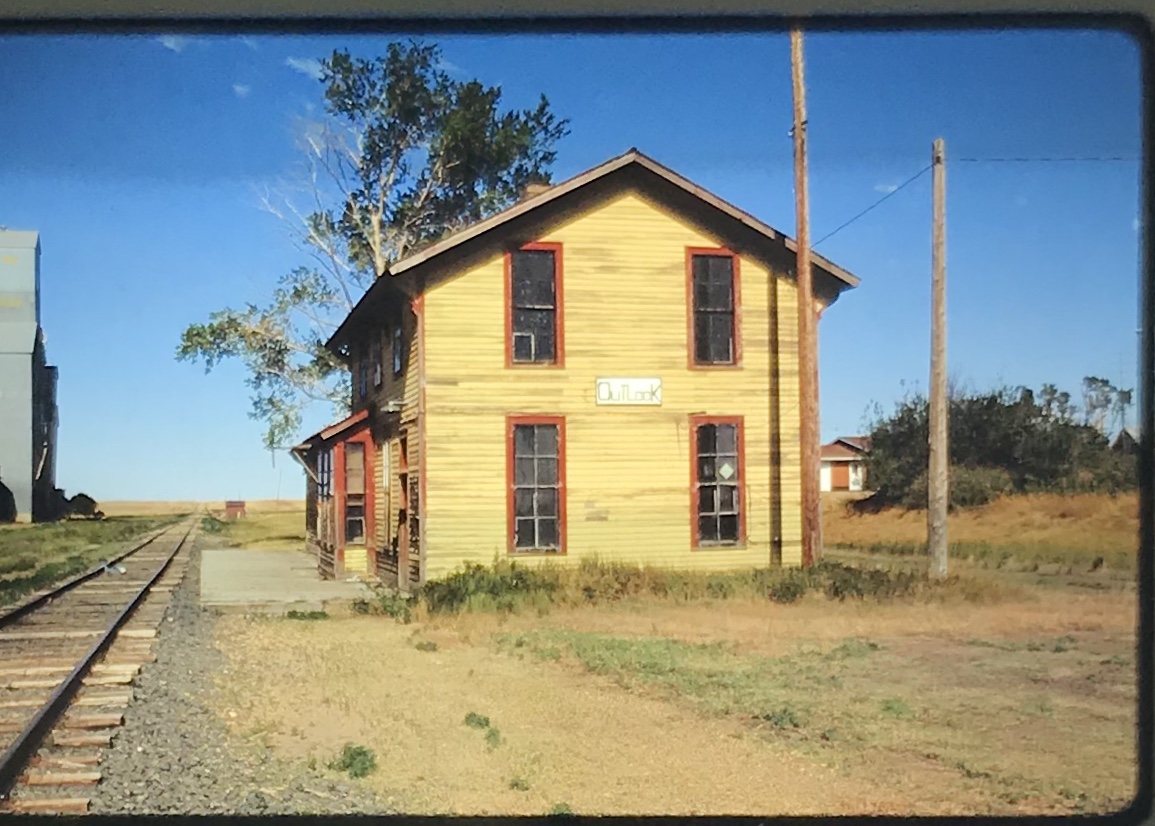

Ryegate received one of the standardized “modern” post office designs from the federal government in the 1970s–the town’s fortunes have remained basically frozen after the Milwaukee Road declared bankruptcy and shut down the tracks in 1980.

Ryegate received one of the standardized “modern” post office designs from the federal government in the 1970s–the town’s fortunes have remained basically frozen after the Milwaukee Road declared bankruptcy and shut down the tracks in 1980.

Helena, the capitol city of Montana, was where I made my home from 1981 to 1985, and served as my base for travels far and wide across the state during my work for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office’s preservation plan in 1984-1985. I started the project at the 1950s modernist Montana Historical Society building next door to the state capitol.

Helena, the capitol city of Montana, was where I made my home from 1981 to 1985, and served as my base for travels far and wide across the state during my work for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office’s preservation plan in 1984-1985. I started the project at the 1950s modernist Montana Historical Society building next door to the state capitol.

Helena then was a small town but a big urban environment, and I used to enjoy exploring its two sided urban landscape: the 1970s “Last Chance Mall” where planners and designers closed the street for a few blocks and inserted a pedestrian mall, thinking that a “walking mall” experience would keep businesses downtown, and then the rest of the downtown before urban planners decided to change it into something it never was.

Helena then was a small town but a big urban environment, and I used to enjoy exploring its two sided urban landscape: the 1970s “Last Chance Mall” where planners and designers closed the street for a few blocks and inserted a pedestrian mall, thinking that a “walking mall” experience would keep businesses downtown, and then the rest of the downtown before urban planners decided to change it into something it never was.

The impetus behind the urban renewal of the 1970s was not only federal dollars through the Model Cities program but also federal presence. Officials wished to anchor the new Last Chance Gulch Urban Renewal project with a Park Avenue section that

The impetus behind the urban renewal of the 1970s was not only federal dollars through the Model Cities program but also federal presence. Officials wished to anchor the new Last Chance Gulch Urban Renewal project with a Park Avenue section that

The pedestrian mall on its west side ends at the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque styled T.C. Power Block, one of my favorite commercial buildings not just in Helena but in all of Montana.

The pedestrian mall on its west side ends at the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque styled T.C. Power Block, one of my favorite commercial buildings not just in Helena but in all of Montana.

This downtown has several architectural landmarks, as you see below with the Art Deco-styled First National Bank building, and then a short block away, a magnificent statement of power and influence, the Montana Club, designed by noted architect Cass Gilbert.

This downtown has several architectural landmarks, as you see below with the Art Deco-styled First National Bank building, and then a short block away, a magnificent statement of power and influence, the Montana Club, designed by noted architect Cass Gilbert.

Once you cross Neill Avenue, you enter a new downtown of 21st century Helena, created by the demolition of the historic Great Northern Railway passenger station in the 1990s and the construction of a new Federal Reserve Bank. Here suddenly was a new downtown

Once you cross Neill Avenue, you enter a new downtown of 21st century Helena, created by the demolition of the historic Great Northern Railway passenger station in the 1990s and the construction of a new Federal Reserve Bank. Here suddenly was a new downtown anchor, similar to that of the 1977 Federal Building on the opposite end of Last Chance Gulch. And the name given to this? the Great Northern Center, where not only the

anchor, similar to that of the 1977 Federal Building on the opposite end of Last Chance Gulch. And the name given to this? the Great Northern Center, where not only the

Federal Reserve lived but also a huge new Federal Courthouse, the Paul G. Hatfield Courthouse (2001-2002), a neoclassical monument of a scale that Helena had not seen since the construction of the State Capitol more than a century earlier, along with its more

Federal Reserve lived but also a huge new Federal Courthouse, the Paul G. Hatfield Courthouse (2001-2002), a neoclassical monument of a scale that Helena had not seen since the construction of the State Capitol more than a century earlier, along with its more modern styled neighbor, the Senator Max Baucus Federal Building. In less than 40 years, the federal presence not only moved from one end of the gulch to another, it had become much larger and architecturally distinct.

modern styled neighbor, the Senator Max Baucus Federal Building. In less than 40 years, the federal presence not only moved from one end of the gulch to another, it had become much larger and architecturally distinct.