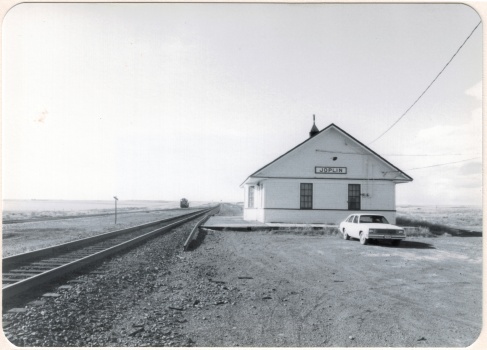

Phillips County is one of my favorite places along the Hi-Line. The Milk River Valley is beautiful; the high plains at Loring and Whitewater are lonesome yet compelling. Empty I guess is how many would describe the county as just over 4250 people live there–in a county of 5,212 square miles.

Loring Hall in 1984

But the diversity of the landscape is memorable. The southern tip of the county is the gateway to the Charles M. Russell National Monument, truly one of the great national parks that few people know about but home to some of most overwhelming views of the Missouri River. North of the Missouri are the southern end of the Little Rocky Mountains and the old mining towns of Zortman and Sandusky.

Abandoned cabins at Zortman, 2013

I have already written about the two Hi-Line towns on the west end (Dodson) and the east end (Saco). Now it is Malta’s turn. When I visited there in 1984 little did I know that Malta was at its population peak.

The 1980 census counted 2,367 residents–never had the town had that many people, and judging from the last three decades, that number is never returning: the population is now under 2,000. The 1980 as a peak population decade–not common among Hi-Line towns, but that wasn’t all that set Malta apart from what I encountered east or west.

Vibrant community institutions anchored the town. The neoclassical Phillips County Courthouse (1921) served as the foundation for the east end residential neighborhood. Designed by Great Falls architect Frank E. Bossout, the red brick courthouse reflects a more restrained expression of the popular classical revival movement, especially compared to Bossout’s earlier more flamboyant Beaux-Arts design for the Hill County Courthouse (c. 1914) in Havre. (I wish they would remove the vines–not good for the bricks.)

Nearby was the Carnegie Library, which had been recently converted to serve as a county museum. In 1984 the community was quite proud of the place, recently (1980) listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Now the museum has moved to new quarters, the Phillips County/ Great Plains Dinosaur Museum, on U.S. Highway 2, where dinosaurs are the primary attraction moreso than local history after a major nationally-noted dinosaur discovery happened in the county in 2000. Yet the town has preserved a notable local house, the Victorian-style H.G. Robinson House (1898), nearby the new museum and there in a domestic setting the town’s early history and settlement is interpreted. The new highway historical/cultural institutions are improvements–but have come at a real cost: a crumbling Carnegie Library, the town’s only National Register-listed property that needs help, now.

Another community institution was the Woman’s Club of the late 1930s, a Rustic-style building that has been discussed earlier in the blog, as part of the institutions that spoke to women’s history that I missed and could not “see” in 1984. But it was also one of three major New Deal buildings that missed–the others being the two-story brick WPA-constructed City Hall and the massive brick “Old Gym” that once served the high school.

Malta also had its share of schools and churches, although again I did not “see” in 1984 the beauty of the contemporary-styled St. Mary’s Catholic Church from c. 1960.

Malta’s business district is the classic T-town type of design found all along the Great Northern line. It too had its anchors: massive grain elevators and grain storage bins, along with the Arts and Crafts styled Great Northern passenger depot, defined the top of the “T”.

Once you took the New Deal-era underpass to go under the tracks, there was the neoclassical First State Bank introducing the “stem” of the T and several blocks of businesses: two movie theaters (both closed now unfortunately) and an Art Deco-styled auto dealership being particularly notable buildings.

Although it was in rough shape Malta also had its railroad/highway park (Trafton Park) on the north side of U.S. 2, where the original U.S. Highway 2 passed using a steel Parker through truss bridge to cross the Milk River.

Nearby was a railroad bridge allowing Great Northern passenger trains to do the same.

Malta, Great Northern Bridge over Milk River, 1984

The town also had its own rodeo grounds, tucked away next to a historic livery stable at the corner of N 2nd Street and N 2nd Avenue. The Maltana Motel–even in 1984 it struck me as a classic 1950s motor court–was the place to stay then, and now. It is one of the few survivors of the “Mom and Pop” roadside abodes I enjoyed in 1984 along the Hi-Line.

Malta has many potential National Register listings–as the many photos here suggest. And all of these heritage assets could be a valuable foundation for new visions and investment. The community is keeping the buildings in use and in general decent repair. But you worry about the future–if the town’s recent trend of population decline continues.