In my work on the state historic preservation plan in 1983-1994, I was excited about the new insight I could bring to the state’s landscape–the impact of the transcontinental railroads and the transportation and settlement corridors that they established in the late 19th and early 20th century. Railroads were of course not a new theme then–books abounded on the railroad barons and the romance of the rails. But as a built environment–that was new, reflecting current scholarship from John Hudson, John Stilgoe, and Roger Grant. So whenever I hit a major railroad division point–like Livingston–I only saw the rails and what happened around them.

That was certainly easy enough to do coming into Livingston from the west on old U.S. 10. The railroad tracks were directly to the north, as well older elements of the town’s roadside architecture, like the exquisite Art Deco-styled radio station, KPRK, now closed for broadcasting (the station’s signal comes from Bozeman) but listed in the National Register. William Fox, a Missoula architect, designed this jewel in 1946.

Continuing west you soon encounter post-World War II service stations and motels, some updated, some much like they were, on the outskirts of town and then, boom, you are in the heart of Livingston, facing the commanding presence of the Northern Pacific depot complex with warehouses–some now converted to new uses–coming first and then

Continuing west you soon encounter post-World War II service stations and motels, some updated, some much like they were, on the outskirts of town and then, boom, you are in the heart of Livingston, facing the commanding presence of the Northern Pacific depot complex with warehouses–some now converted to new uses–coming first and then

massive passenger station itself. Opened in 1902, the passenger station was an architectural marvel for the new state, designed by Reed and Stem, who would continue on to great fame as the architects of Grand Central Station in New York City. The station, interestingly, is not Classical Revival in style–certainly the choice of most architects for their grand gateways along the nation’s rail line–but a more restrained interpretation of Renaissance Revival style, completed in red brick.

massive passenger station itself. Opened in 1902, the passenger station was an architectural marvel for the new state, designed by Reed and Stem, who would continue on to great fame as the architects of Grand Central Station in New York City. The station, interestingly, is not Classical Revival in style–certainly the choice of most architects for their grand gateways along the nation’s rail line–but a more restrained interpretation of Renaissance Revival style, completed in red brick.

The building is not particularly inviting for locals coming from the business district to the depot–that was not its primary audience. Rather the grand entrance is track side, where passengers headed to Yellowstone National Park could depart for food, fun, frivolity, whatever they needed before the journey into the wildness of Yellowstone.

The building is not particularly inviting for locals coming from the business district to the depot–that was not its primary audience. Rather the grand entrance is track side, where passengers headed to Yellowstone National Park could depart for food, fun, frivolity, whatever they needed before the journey into the wildness of Yellowstone.

Travelers were welcome to use the grand covered walkways to enter the depot proper, or to take a side visit to the railroad’s cafe, Martin’s as I

Travelers were welcome to use the grand covered walkways to enter the depot proper, or to take a side visit to the railroad’s cafe, Martin’s as I

knew it back in the day, a place that rarely slept and always had good pie. The cafe changed its orientation from the railroad to the road as automobile travelers on U.S. 10 began to dominate the tourist market. Now it has been restored as a local brew pub.

knew it back in the day, a place that rarely slept and always had good pie. The cafe changed its orientation from the railroad to the road as automobile travelers on U.S. 10 began to dominate the tourist market. Now it has been restored as a local brew pub.

The interior of the passenger station once held large public spaces for travelers and then more intimate spaces themed to either men or women.

Upstairs were spaces for offices, company lodging, and other company business. The station was the railroad’s urban outpost was what was then still the Montana frontier–its statement of taste and sophistication still reverberates today even as the depot no longer serves passengers (except for occasion excursion trains Amtrak doesn’t run here anymore) and serves as a railroad and Park County museum.

Thirty years ago, the overwhelming imprint of the Northern Pacific on the surrounding built environment was all I could see. At one corner was one of the first local historic preservation projects, an adaptive reuse effort to create the Livingston Bar and Grille (once popular with the valley’s Hollywood crowd).

Directly facing the center of the passenger station was the mammoth Murray Hotel–a flea bag operation in the 1980s but now recently restored as a hipster place to be, especially its signature bar.

Directly facing the center of the passenger station was the mammoth Murray Hotel–a flea bag operation in the 1980s but now recently restored as a hipster place to be, especially its signature bar.

My throwback place back in the 1980s, however, was Gil’s. It was next to the Murray and the place to get the cheesy souvenirs you equate with western travel in the second half of the 20th century.

Imagine my pleasant surprise last year when I found that Gil’s still existed but now had been converted into a decidedly up-scale establishment, far removed from the 1980s.

Imagine my pleasant surprise last year when I found that Gil’s still existed but now had been converted into a decidedly up-scale establishment, far removed from the 1980s.

I don’t know if I have encountered a more fundamentally changed place–cheap trinkets gone, let the wood-fired pizzas come on.

I don’t know if I have encountered a more fundamentally changed place–cheap trinkets gone, let the wood-fired pizzas come on.

I was not so blinded in 1984 by the concept of the “metropolitan corridor” that I ignored the distinctive Victorian storefronts of Livingston–how could I since they all, in a way, fed into the tracks. But when I got to the end of that distinctive business district and watched the town, in my

I was not so blinded in 1984 by the concept of the “metropolitan corridor” that I ignored the distinctive Victorian storefronts of Livingston–how could I since they all, in a way, fed into the tracks. But when I got to the end of that distinctive business district and watched the town, in my

mind, fade into the Rockies, I had captured the obvious but had missed the bigger picture–that’s the next story.

mind, fade into the Rockies, I had captured the obvious but had missed the bigger picture–that’s the next story.

As the highway leaves the central plains east of Great Falls, it heads east through coal country (see the earlier post on Belt) and south into the Little Belt Mountains and the old mining towns of Monarch and Neihart (above). Both Cascade County towns are proud of their heritage, a story embodied in the Monarch-Neihart School, a wonderful bit of log craftsmanship from the New Deal era, a WPA project finished in 1940 that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

As the highway leaves the central plains east of Great Falls, it heads east through coal country (see the earlier post on Belt) and south into the Little Belt Mountains and the old mining towns of Monarch and Neihart (above). Both Cascade County towns are proud of their heritage, a story embodied in the Monarch-Neihart School, a wonderful bit of log craftsmanship from the New Deal era, a WPA project finished in 1940 that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When I last visited there in 2015 the combined route of U.S. 89 and 12, which passes in front of the courthouse and the center of town, was being rebuilt, giving the historic business district the look of a ghost town.

When I last visited there in 2015 the combined route of U.S. 89 and 12, which passes in front of the courthouse and the center of town, was being rebuilt, giving the historic business district the look of a ghost town.

U.S. Highway 89 continues south, crossing the historic corridor of the Milwaukee Road at Ringling, another Meagher County town discussed in an earlier post, marked by the landmark St. John’s Catholic Church.

U.S. Highway 89 continues south, crossing the historic corridor of the Milwaukee Road at Ringling, another Meagher County town discussed in an earlier post, marked by the landmark St. John’s Catholic Church. Travelers continuing south soon find themselves in Park County, entering the Shields River Valley just north of Wilsall, where highway markers and monuments, like that for “Thunder Jack” (2006) by sculptor Gary Kerby, convey the significance of the place.

Travelers continuing south soon find themselves in Park County, entering the Shields River Valley just north of Wilsall, where highway markers and monuments, like that for “Thunder Jack” (2006) by sculptor Gary Kerby, convey the significance of the place.

Wilsall was not much a place 30 years ago, a small trade town on the edge of a Northern Pacific Railroad spur line, a past still recalled by the tall elevator and old railroad corridor.

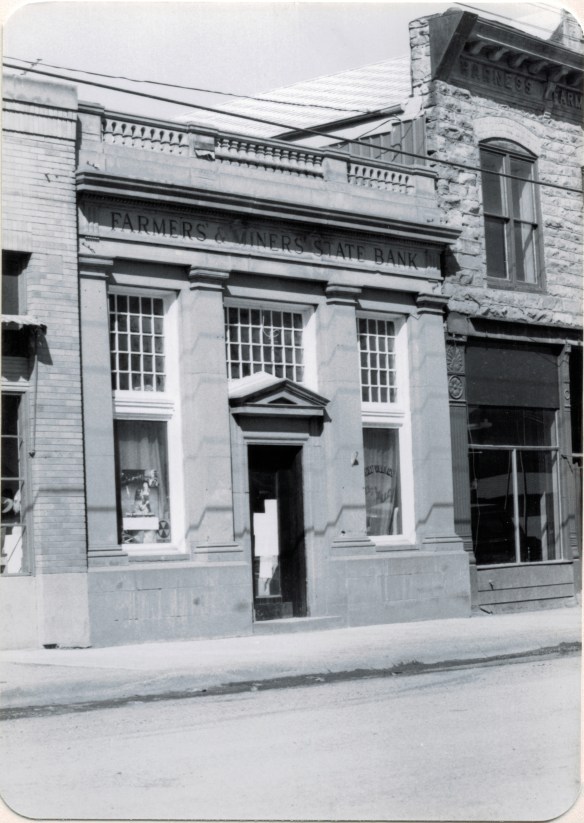

Wilsall was not much a place 30 years ago, a small trade town on the edge of a Northern Pacific Railroad spur line, a past still recalled by the tall elevator and old railroad corridor. But the growing popularity of the Shields River Valley has led to a new boom in Walsall, with old banks converted into bars and old general stores

But the growing popularity of the Shields River Valley has led to a new boom in Walsall, with old banks converted into bars and old general stores

Clyde Park Tavern is still the place to go for an adult beverage, or two. Historic grain elevators still serve local ranchers, marking the railroad line that defined the town’s landscape until the impact of the highway in the early 20th century.

Clyde Park Tavern is still the place to go for an adult beverage, or two. Historic grain elevators still serve local ranchers, marking the railroad line that defined the town’s landscape until the impact of the highway in the early 20th century.

project, and the Art Moderne landmark Intermountain bus station–once so proudly featured in the Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges movie, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,” part of that decade from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s when Montana was suddenly in the lens of Hollywood.

project, and the Art Moderne landmark Intermountain bus station–once so proudly featured in the Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges movie, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,” part of that decade from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s when Montana was suddenly in the lens of Hollywood. All of these buildings and places help to give Great Falls its unique sense of self, and its sense of achievement and promise. And that is not to even mention the fun, funky stuff, such as the Polar Bears and having the

All of these buildings and places help to give Great Falls its unique sense of self, and its sense of achievement and promise. And that is not to even mention the fun, funky stuff, such as the Polar Bears and having the supper club experience of 50 years ago at Borrie’s in Black Eagle. Stepping back into time, or looking into a future where heritage stands next to the

supper club experience of 50 years ago at Borrie’s in Black Eagle. Stepping back into time, or looking into a future where heritage stands next to the atomic age, Great Falls and its environs–from Fort Benton to the northeast to Fort Shaw to the southwest–can give you that memorable heritage area experience.

atomic age, Great Falls and its environs–from Fort Benton to the northeast to Fort Shaw to the southwest–can give you that memorable heritage area experience. Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation.

Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation. Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others

Along the Missouri River is Paris Gibson Park, deep in the heart of Great Falls, Montana. Gibson was one of the classic civic capitalists of the late 19th century who understood that as the community prospered he too would achieve this dream of building a great western empire, with his town of Great Falls as the center. Almost 100 years after his death, in 2015, residents, preservationists, historians, and economic developers began discussions on establishing a heritage area, centered on Great Falls, but encompassing the Missouri River as the thread between the plains and mountains, that has shaped the region, and the nation, for hundreds of years. I strongly endorse the discussion and will spend the next several posts exploring key resources in Cascade County that could serve as the foundation for a larger regional story.

Along the Missouri River is Paris Gibson Park, deep in the heart of Great Falls, Montana. Gibson was one of the classic civic capitalists of the late 19th century who understood that as the community prospered he too would achieve this dream of building a great western empire, with his town of Great Falls as the center. Almost 100 years after his death, in 2015, residents, preservationists, historians, and economic developers began discussions on establishing a heritage area, centered on Great Falls, but encompassing the Missouri River as the thread between the plains and mountains, that has shaped the region, and the nation, for hundreds of years. I strongly endorse the discussion and will spend the next several posts exploring key resources in Cascade County that could serve as the foundation for a larger regional story.

Thirty years later, Belt’s population had bottomed out, declining to under 600 by the time of the 2010 census. But both times I have stopped by, in 2013 and 2015, the town has a sense of life about it, and hope. The town’s two historic taverns, the Harvest Moon Tavern and the Belt Creek Brew Pub, as well as the Black Diamond Bar and Supper Club attract visitors from nearby Great Falls and elsewhere, giving the place a sense of life at evenings and weekends.

Thirty years later, Belt’s population had bottomed out, declining to under 600 by the time of the 2010 census. But both times I have stopped by, in 2013 and 2015, the town has a sense of life about it, and hope. The town’s two historic taverns, the Harvest Moon Tavern and the Belt Creek Brew Pub, as well as the Black Diamond Bar and Supper Club attract visitors from nearby Great Falls and elsewhere, giving the place a sense of life at evenings and weekends.

When planners talk about heritage areas, they often focus on the contributions of local entrepreneurs who take historic buildings, like the Pioneer above, and breathe new life into them. Throughout small town Montana and urban commercial districts, new breweries and distilleries are creating such opportunities.

When planners talk about heritage areas, they often focus on the contributions of local entrepreneurs who take historic buildings, like the Pioneer above, and breathe new life into them. Throughout small town Montana and urban commercial districts, new breweries and distilleries are creating such opportunities.

Belt has a range of historic buildings, mostly of vernacular two-part commercial style that speak strongly to the boom of 1900 to 1920. The Victorian-styled cornice of the Belt Hardware Store (1896) speaks to the town’s origins. The Knights of Pythias Lodge of 1916 has been restored as a community theater, another reason for visitors to stop and explore.

Belt has a range of historic buildings, mostly of vernacular two-part commercial style that speak strongly to the boom of 1900 to 1920. The Victorian-styled cornice of the Belt Hardware Store (1896) speaks to the town’s origins. The Knights of Pythias Lodge of 1916 has been restored as a community theater, another reason for visitors to stop and explore. The result is a living cultural experience, since nothing in Belt is over-restored or phony feeling. It is still a gritty, no frills place. That feel is complemented by the Belt museum, which is housed in a historic jail on road down into town and within sight on a railroad trestle, a reminder of what literally drove the town’s development, coal for the railroads.

The result is a living cultural experience, since nothing in Belt is over-restored or phony feeling. It is still a gritty, no frills place. That feel is complemented by the Belt museum, which is housed in a historic jail on road down into town and within sight on a railroad trestle, a reminder of what literally drove the town’s development, coal for the railroads. During the 1984 survey, I gave the jail a good bit of attention since this stone building spoke to the craftsmanship of the era, the centrality of local government as the town developed, and the reality that this building was the only thing in Belt listed in the National Register of Historic Places. But in 2004 the state historic preservation office approved the Belt commercial historic district, and that designation has done much to drive the town’s recent revival. Belt is just the first place that speaks to the promise of the Great Falls heritage area concept.

During the 1984 survey, I gave the jail a good bit of attention since this stone building spoke to the craftsmanship of the era, the centrality of local government as the town developed, and the reality that this building was the only thing in Belt listed in the National Register of Historic Places. But in 2004 the state historic preservation office approved the Belt commercial historic district, and that designation has done much to drive the town’s recent revival. Belt is just the first place that speaks to the promise of the Great Falls heritage area concept.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town. How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history.

How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history. Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society.

Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society. What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense.

What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense. Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation.

Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation. Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods. The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and

The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today.

residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today. As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis.

As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis. Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.