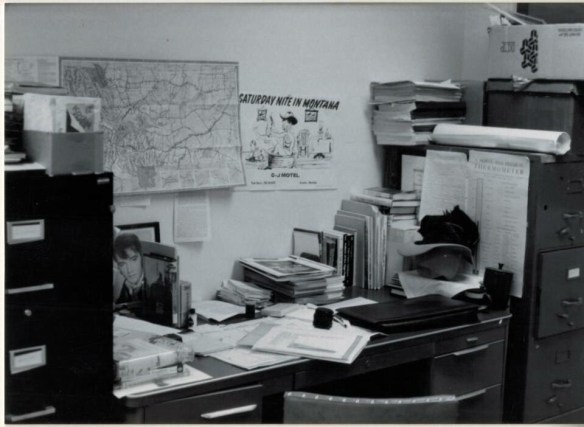

The vast majority of my effort to document and think about the historic landscapes of Montana lie with two time periods, 1984-85 and 2012-16. But in between those two focused periods, other projects at the Western Heritage Center in Billings brought me back to the Big Sky Country. Almost always I found a way to carve out a couple of additional days to get away from the museum and study the many layers of history, and change, in the landscape by taking black and white images as I had in 1984-85. One such trip came in 1999, at the end of the 20th century.

In Billings itself I marveled at the changes that historic preservation was bringing to the Minnesota Avenue district. The creation of an “Internet cafe” (remember those?) in the McCormick Block was a guaranteed stop.

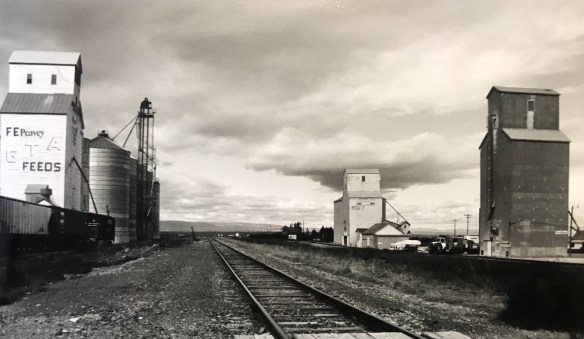

But my real goal was to jet up highways 191 and 80 to end up in Fort Benton. Along the way I had to stop at Moore, one of my favorite Central Montana railroad towns, and home to a evocative set of grain elevators.

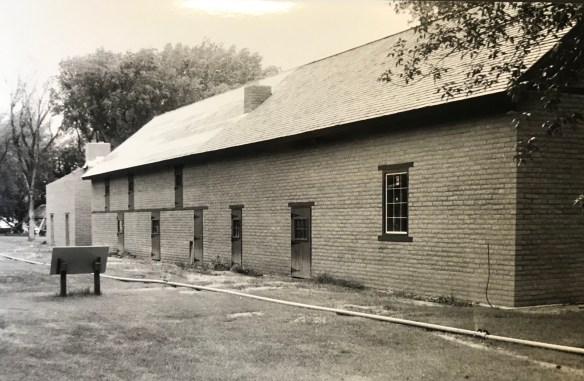

Then a stop for lunch at the Geraldine bar and the recently restored Geraldine depot, along a historic spur of the Milwaukee Road. I have always loved a stop in this plains country town and this day was especially memorable as residents showed off what they had accomplished in the restoration. Another historic preservation plus!

Then it was Fort Benton, a National jewel seemingly only appreciated by locals, who faced an often overwhelming task for preserving and finding sustainable new uses for the riverfront buildings.

It was exciting to see the recent goal that the community eagerly discussed in 1984–rebuilding the historic fort.

A new era for public interpretation of the northern fur trade would soon open in the new century: what a change from 1984.

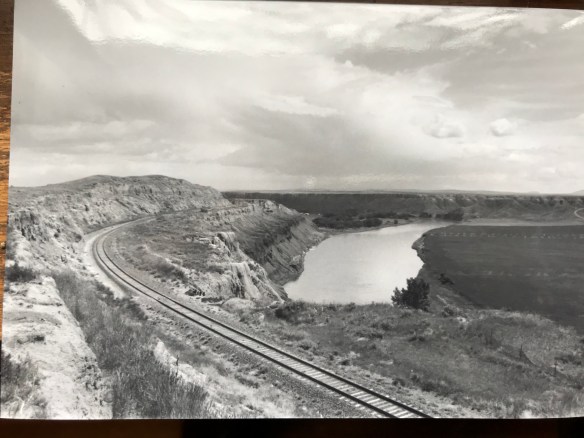

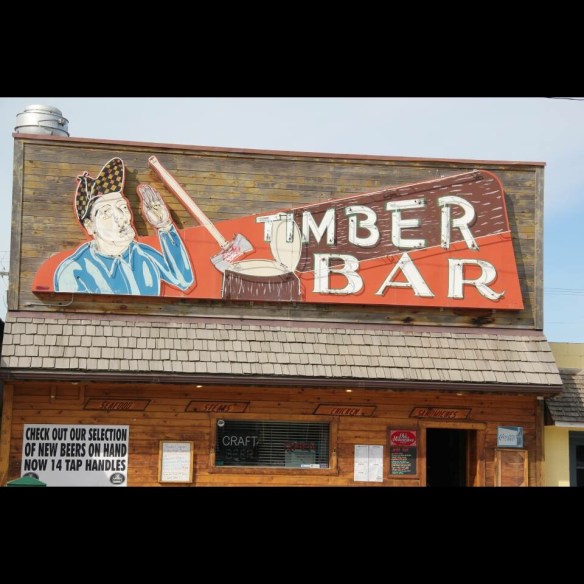

I beat a quick retreat back to the south, following the old Manitoba Road route along the Missouri and US Highway 87 and back via highway 89 to the Yellowstone Valley. I had to pay a quick tribute to Big Timber, and grab a brew at the Big Timber

Bar. The long Main Street in Big Timber was obviously changing–new residents and new businesses. Little did I know how much change would come in the new century.

One last detour came on the drive to see if the absolutely spectacular stone craftsmanship of the Absarokee school remained in place–it did, and still does.

My work in Tennessee had really focused in the late 1990s on historic schools: few matched the distinctive design of Absarokee. I had to see it again.

Like most trips in the 1990s to Billings I ended up in Laurel–I always felt this railroad town had a bigger part in the history of Yellowstone County than

generally accepted. The photos I took in 1999 are now striking– had any place in the valley changed more than Laurel in the 21st century?

chops away and the beer is still cold. That is what you need on the road.

chops away and the beer is still cold. That is what you need on the road.

Community Center Bowl in Hardin, Big Horn County, is a wonderful recreational space, with its bays defined by c. 1960 styled “picture windows” framed in glass blocks. The owners have refurbished the lanes two years ago–this institution still has years left in it.

Community Center Bowl in Hardin, Big Horn County, is a wonderful recreational space, with its bays defined by c. 1960 styled “picture windows” framed in glass blocks. The owners have refurbished the lanes two years ago–this institution still has years left in it.

From the southeast corner of the state to its northwest corner–the Trojan Lanes (so named for the school mascot) in Troy, Montana. Here you find the type of alley that is common throughout the small towns of Big Sky Country. Not only do you have a recreational center but you often have the best family restaurant in town. That’s the

From the southeast corner of the state to its northwest corner–the Trojan Lanes (so named for the school mascot) in Troy, Montana. Here you find the type of alley that is common throughout the small towns of Big Sky Country. Not only do you have a recreational center but you often have the best family restaurant in town. That’s the case where at Troy’s Trojan as well as–returning to the southeast corner–the Powder River Lanes in Broadus. This tiny county seat has lost several of its classic cafes from the 1980s–the Montana Bar and Cafe on the opposite side of the town square being my favorite in 1984–but Powder River Lanes makes up for it.

case where at Troy’s Trojan as well as–returning to the southeast corner–the Powder River Lanes in Broadus. This tiny county seat has lost several of its classic cafes from the 1980s–the Montana Bar and Cafe on the opposite side of the town square being my favorite in 1984–but Powder River Lanes makes up for it. I am sorta partial to the small-town lanes, like the Lucky Strike above in Ronan, Lake County. Located next door to “Entertainer Theatre,” this corner of the town is clearly its center for pop culture experience.

I am sorta partial to the small-town lanes, like the Lucky Strike above in Ronan, Lake County. Located next door to “Entertainer Theatre,” this corner of the town is clearly its center for pop culture experience. Another fav–admittedly in a beat-up turn of the 20th century building–is Roper Lanes and Lounge in Whitehall, Jefferson county, in the southwest corner of the state. Gotta love the painted sign over the entrance–emojis before they were called emojis.

Another fav–admittedly in a beat-up turn of the 20th century building–is Roper Lanes and Lounge in Whitehall, Jefferson county, in the southwest corner of the state. Gotta love the painted sign over the entrance–emojis before they were called emojis.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950. Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural

Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City.

statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City. Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive.

at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive. Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor

Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley. The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

Bozeman has boomed with many new chef-driven restaurants but of the downtown establishments my favorite for good fresh, creative food remains the Co-Op Downtown nestled within the Gallatin Block, a historic building, tastefully renovated, in the downtown historic district.

Bozeman has boomed with many new chef-driven restaurants but of the downtown establishments my favorite for good fresh, creative food remains the Co-Op Downtown nestled within the Gallatin Block, a historic building, tastefully renovated, in the downtown historic district.

head to Miles City, which is the place to go if you wonder, still, “where’s the beef” and a city that is the proud home of the famous Montana Bar.

head to Miles City, which is the place to go if you wonder, still, “where’s the beef” and a city that is the proud home of the famous Montana Bar.

within New Deal landscape that forever changed the look of this region in the 1930s. Locals and tourists mix together–because the hotel is the only place to go, unless you want to backtrack to Glasgow and check out Sam’s Supper Club on U.S. Highway 2, and its equally neat 1960s roadside look.

within New Deal landscape that forever changed the look of this region in the 1930s. Locals and tourists mix together–because the hotel is the only place to go, unless you want to backtrack to Glasgow and check out Sam’s Supper Club on U.S. Highway 2, and its equally neat 1960s roadside look.

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89.

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89. Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta  won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined?

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined? Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

entertained generations of Grizzly students and fans–note the window mural. But it is just one of several favorite Stockman’s Bars I have encountered in my Montana fieldwork. My top choice is actually on the other end of the state–almost in North Dakota in fact–the Stockman’s Bar in Wibaux.

entertained generations of Grizzly students and fans–note the window mural. But it is just one of several favorite Stockman’s Bars I have encountered in my Montana fieldwork. My top choice is actually on the other end of the state–almost in North Dakota in fact–the Stockman’s Bar in Wibaux.

The woman’s club began c. 1921 and had already made a major contribution to the town’s well-being in establishing its first library. After World War II, however, club members felt they should once again help build the community, by building a youth center and veterans memorial garden. Mrs. Norman Good proposed the project in 1946 and Mrs. G. D. Martin provided the first substantial donation. The club then held fundraisers of all sorts. By 1950, construction was underway, with contractor Clyde Wilson building the center with logs from Colby and Sons in Kila, Montana.

The woman’s club began c. 1921 and had already made a major contribution to the town’s well-being in establishing its first library. After World War II, however, club members felt they should once again help build the community, by building a youth center and veterans memorial garden. Mrs. Norman Good proposed the project in 1946 and Mrs. G. D. Martin provided the first substantial donation. The club then held fundraisers of all sorts. By 1950, construction was underway, with contractor Clyde Wilson building the center with logs from Colby and Sons in Kila, Montana. As the youth center was under construction, the woman’s club also reached an agreement with the school board to use land for the construction of a new football field, named McQuitty Field. Located behind the youth center, the field opened in 1950.

As the youth center was under construction, the woman’s club also reached an agreement with the school board to use land for the construction of a new football field, named McQuitty Field. Located behind the youth center, the field opened in 1950.

Thus, on U.S. Highway 12 lies the public recreation heart of Harlowton–a postwar gift of residents and service clubs to the community. In 1956, the woman’s club deeded the Youth Center to the Kiwanis Club, which still manages it today.

Thus, on U.S. Highway 12 lies the public recreation heart of Harlowton–a postwar gift of residents and service clubs to the community. In 1956, the woman’s club deeded the Youth Center to the Kiwanis Club, which still manages it today.

Road, it once also had several hotels and more short-term housing for workers and travelers–a good bit of that has disappeared, or is disappearing.

Road, it once also had several hotels and more short-term housing for workers and travelers–a good bit of that has disappeared, or is disappearing.

It is difficult to visit Harlowton and not notice the mammoth Montana Flour Mills set of concrete grain silos–today’s silent sentinels of what ranchers once produced in abundance in these lands.

It is difficult to visit Harlowton and not notice the mammoth Montana Flour Mills set of concrete grain silos–today’s silent sentinels of what ranchers once produced in abundance in these lands. The mill, made from locally quarried stone, came within months of the completion of the railroad to Harlowton–the concrete silos reflected the hopes of investors and local ranchers, as grain production soared in the 1910s–reaching some 1.2 million bushels in 1918. It wasn’t called Wheatland County for nothing. I still wish the big electric sign that once adorned the silos was still there.

The mill, made from locally quarried stone, came within months of the completion of the railroad to Harlowton–the concrete silos reflected the hopes of investors and local ranchers, as grain production soared in the 1910s–reaching some 1.2 million bushels in 1918. It wasn’t called Wheatland County for nothing. I still wish the big electric sign that once adorned the silos was still there.