U.S. Highway 2 east of Kalispell has grown into a four-lane highway (mostly–topography thus far has kept it as a two-lane stretch west of Hungry Horse) designed to move travelers back and forth from Kalispell to Glacier National Park. In my 1984-85 state historic preservation plan work, I thought of Columbia Falls, Hungry Horse, and Martin

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

There is much more than the highway to Columbia Falls, as the three building blocks above indicate, not to mention the lead image of this blog, the town’s Masonic Lodge which has been turned into one huge public art mural about the town’s history as well as its surrounding landscape. Go to the red brick Bandit’s Bar above, and you soon discover that Columbia Falls has a good sense of itself, and even confidence that it can survive new challenges as its population has soared by over 2,000 residents since the 1980s, totaling over 5,000 today.

Once solely dependent on the Montana Veterans’ Home (1896), which is now a historic district, and then relying on the Weyerhaeuser sawmill for year round employment, Columbia Falls faces a different future now once the mill closed in the summer of 2016, taking away 200 jobs. As the historic business buildings above indicate, historic preservation could be part of that future, as the downtown’s mix of classic Western Commercial blocks mesh with modern takes on Rustic and Contemporary design and are complemented, in turn, by historic churches and the Art Deco-influenced school.

Once you leave the highway, in other words, real jewels of turn of the 20th century to mid-20th century design are in the offing. In 1984–I never looked that deep.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

Here I am thinking primarily of the contemporary design of the Visitors Center–its stone facade suggesting its connection to the now covered river bluffs but the openness of its interior conveying the ideas of space associated with 1950s design.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

Martin City is just enough off of U.S. Highway 2–it is situated more on the historic Great Northern Railroad corridor–to miss out on the gateway boom of the last 30 years, although with both the Southfork Saloon and the Deer Lick Saloon it retains its old reputation as a rough-edged place for locals.

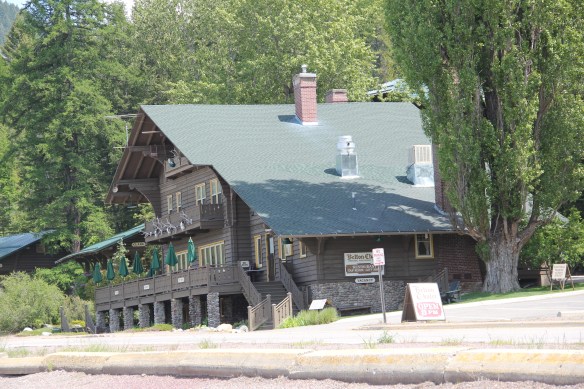

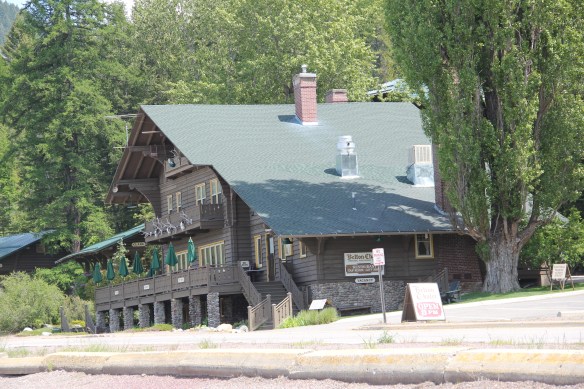

For railroad travelers in the first half of the 20th century, West Glacier was THE west gateway into Glacier National Park. The Great Northern Railway developed both the classic Rustic-styled passenger station and the adjacent Arts and Crafts/Chalet styled Belton Chalet Hotel in 1909-1910, a year before Congress created Glacier National Park.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

The Cutter buildings for the railroad between 1909-1913 set a design standard for West Glacier to follow, be it through a modern-day visitor center and a post office to the earlier mid-20th century era of the local school and then gas stations and general stores for tourists entering the national park by automobile.

This blog has never hidden the fact, however, that my favorite Glacier gateway in Flathead County is miles to the east along U.S. Highway 2 at the old railroad town of Essex, where the railroad still maintains facilities to help push freight trains over the Continental Divide. The Izaak Walton Inn was one of the first National Register assignments given to

me by State Historic Preservation Officer Marcella Sherfy–find the facts, she asked, to show that this three story bunk house, railroad offices, and local post merited exceptional significance for the National Register. Luckily I did find those facts and shaped that argument–the owners then converted a forgotten building into a memorable historical experience. Rarely do I miss a chance to spend even a few minutes here, to watch and hear the noise of the passing trains coming from the east or from the west and to catch a sunset high in the mountains of Flathead County.

Then in October 2017, someone set a fire that almost totally destroyed the school building. When I pulled into Big Timber the following May, I expected to see a parking lot or at least an empty lot (the local Episcopal Church had purchased the property). The damaged building was still there, however, giving me one final chance to take an image, one that now represents dreams dashed, and yet another historic building gone from the Montana landscape.

Then in October 2017, someone set a fire that almost totally destroyed the school building. When I pulled into Big Timber the following May, I expected to see a parking lot or at least an empty lot (the local Episcopal Church had purchased the property). The damaged building was still there, however, giving me one final chance to take an image, one that now represents dreams dashed, and yet another historic building gone from the Montana landscape.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors. Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

St. Joseph Catholic Church, perched now on a barren bluff facing the lake, was moved about 2.5 miles east to its present location in 1954. Originally near the river in what was then known as the Canton Valley settlement, the church building is one of the state’s oldest, dating to 1874-1875 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The proud Gothic styled church is the remnant of one of the valley’s earliest settlements.

St. Joseph Catholic Church, perched now on a barren bluff facing the lake, was moved about 2.5 miles east to its present location in 1954. Originally near the river in what was then known as the Canton Valley settlement, the church building is one of the state’s oldest, dating to 1874-1875 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The proud Gothic styled church is the remnant of one of the valley’s earliest settlements.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley. The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89.

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89. Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta  won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined?

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined? Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

At first glance, Dutton is like many northern plains railroad towns, located on the Great Northern Railway spur line between Shelby and Great Falls. The false front of Mike’s Tavern, then other plain, functional one-story buildings–we have seen hundreds of similar scenes across the Big Sky Country.

At first glance, Dutton is like many northern plains railroad towns, located on the Great Northern Railway spur line between Shelby and Great Falls. The false front of Mike’s Tavern, then other plain, functional one-story buildings–we have seen hundreds of similar scenes across the Big Sky Country. Then, suddenly, there is the cool mid-century modernism of the Dutton-Brady School (Brady is another neighboring railroad town), a style also embraced by the Bethany Lutheran Church.

Then, suddenly, there is the cool mid-century modernism of the Dutton-Brady School (Brady is another neighboring railroad town), a style also embraced by the Bethany Lutheran Church.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

By the late 1980s there was little doubt that a substantial development boom was underway in Flathead County. In the town near the Flathead Lake, like Bigfork, above, the boom dramatically altered both the density and look of the town. In the northern half of the county Whitefish suddenly became a sky resort center. In 1988, during a return visit to Montana, I did not like what I encountered in Flathead County–and thus I stayed away for the next 27 years years, until the early summer of 2015.

By the late 1980s there was little doubt that a substantial development boom was underway in Flathead County. In the town near the Flathead Lake, like Bigfork, above, the boom dramatically altered both the density and look of the town. In the northern half of the county Whitefish suddenly became a sky resort center. In 1988, during a return visit to Montana, I did not like what I encountered in Flathead County–and thus I stayed away for the next 27 years years, until the early summer of 2015.

The dam is 422 feet tall and stretches across the river for 3,055 feet–well over a 1/2 mile. It creates a huge reservoir, extending 90 miles to the north and into British Columbia, among the ten largest reservoirs in the nation. And like that, a historic river valley became a recreational lake in a joint project between the United States and Canada.

The dam is 422 feet tall and stretches across the river for 3,055 feet–well over a 1/2 mile. It creates a huge reservoir, extending 90 miles to the north and into British Columbia, among the ten largest reservoirs in the nation. And like that, a historic river valley became a recreational lake in a joint project between the United States and Canada.

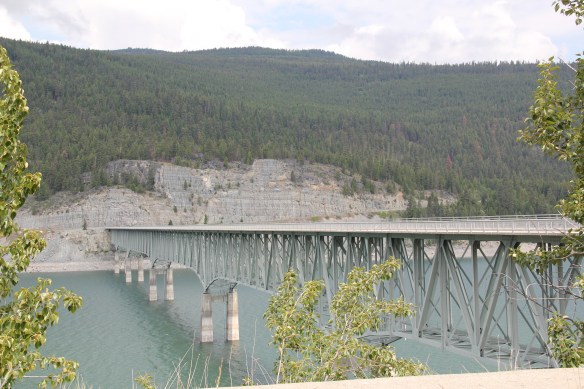

The Lake Koocanusa Bridge, which provides access to a Mennonite community and a backroad way to Yaak, is the state’s longest, and in many ways, its most spectacular multi-truss bridge. The bridge is 2,437 feet long, and stands, depending on water level, some 270 feet above the lake.

The Lake Koocanusa Bridge, which provides access to a Mennonite community and a backroad way to Yaak, is the state’s longest, and in many ways, its most spectacular multi-truss bridge. The bridge is 2,437 feet long, and stands, depending on water level, some 270 feet above the lake.

There was no interpretation at this bridge in 1984, but the scenic highway designation has led to the placement of overlooks and interpretive markers at some places along the lake. One wishes for the same at the Montana town that the lake displaced, Rexford. This once

There was no interpretation at this bridge in 1984, but the scenic highway designation has led to the placement of overlooks and interpretive markers at some places along the lake. One wishes for the same at the Montana town that the lake displaced, Rexford. This once small river town had to move, or be inundated. And since the move took place in the mid to late 1960s, the town embodies the mid-century modern aesthetic, both in the design of many buildings but also in the town plan itself as the federal government finished relocating Rexford in the early 1970s.

small river town had to move, or be inundated. And since the move took place in the mid to late 1960s, the town embodies the mid-century modern aesthetic, both in the design of many buildings but also in the town plan itself as the federal government finished relocating Rexford in the early 1970s.

school by itself is a fascinating statement of both design but also a community’s determination to stay, no matter what the federal government threw their way. Needless to say, in 1984 I paid Rexford no attention–nothing historic was there, it was all new. But now it is clear what a important place in Lincoln County’s 20th century history Rexford came to be.

school by itself is a fascinating statement of both design but also a community’s determination to stay, no matter what the federal government threw their way. Needless to say, in 1984 I paid Rexford no attention–nothing historic was there, it was all new. But now it is clear what a important place in Lincoln County’s 20th century history Rexford came to be.