Gallatin County is one of the oldest white settlement landscapes in Montana. The Bozeman Trail to the western gold fields introduced settlers from the 1860s to 1880 to the potentially rich land of the Gallatin Valley. Then the Northern Pacific Railroad opened the heart of the valley to development as the tracks crossed the Bozeman Pass in the early 1880s.

Manhattan was not originally Manhattan, but named Moreland, as discussed in an earlier blog about the effort to build a barley empire in this part of Gallatin County at the turn of the century by the Manhattan Malting Company and its industrial works here and in Bozeman. But the existing railroad corridor, along with the surviving one- and two-

Manhattan was not originally Manhattan, but named Moreland, as discussed in an earlier blog about the effort to build a barley empire in this part of Gallatin County at the turn of the century by the Manhattan Malting Company and its industrial works here and in Bozeman. But the existing railroad corridor, along with the surviving one- and two-

story commercial buildings facing the tracks (and old U.S. Highway 10), always made a drive through Manhattan a pleasant diversion as I crisscrossed Montana in 1984-1985. The town has a strong 1920s feel, in large part because of an earthquake that destroyed a good bit of the town’s original buildings in 1925.

Manhattan has changed significantly over 30 years–as the storefronts above suggest–just not to the degree of Belgrade. But you wonder if its time is not coming. From 1980 to 1990–the years which I visited the town the most–its population barely ticked up from 988 to 1032. In the 25 years since the population has expanded to an estimated 1600.

The historic auto garage from c. 1920 above is one of the most significant landmarks left upon old U.S. 10, and I am glad it is still used for its original function in the 21st century.

The historic auto garage from c. 1920 above is one of the most significant landmarks left upon old U.S. 10, and I am glad it is still used for its original function in the 21st century.

Community landmarks-fraternal lodges, the wonderful 1960s modernism of the Manhattan public school, and historic church buildings add character and a sense of stability to Manhattan.

Different variations on the Bungalow style characterize the town’s historic neighborhood. Buildings, like along old U.S. 10, have changed but still that sense of the early 20th century comes strongly across as you walk along Manhattan’s sidewalks.

At the same time, the new face of Manhattan is appearing in developments just south of the railroad corridor and in new construction facing the tracks. Both buildings “fit” into the town but stylistically and in materials belong more to the 21st century American suburb, especially when compared to the remaining vernacular commercial buildings.

Is Manhattan at a crossroads between its long history as a minor symmetrical-plan town along the Northern Pacific Railroad and its new place as one of the surrounding rural suburbs of the Bozeman area? Probably.

But it has many positives in place to keep its character yet change with the times. Many residents are using historic buildings for their businesses and trades. Others are clearly committed to the historic residential area–you can’t help but be impressed by the town’s well-kept historic homes and well-maintained yards and public areas.

But it has many positives in place to keep its character yet change with the times. Many residents are using historic buildings for their businesses and trades. Others are clearly committed to the historic residential area–you can’t help but be impressed by the town’s well-kept historic homes and well-maintained yards and public areas.

Like at Belgrade, historic preservation needs to have a greater focus here. Nothing in the town is listed in the National Register but as these photos suggest, certainly there is National Register potential in this town.

From 1983-85 Belgrade became one of my favorite Northern Pacific railroad towns. Often I would leave the interstate here, stop at truly one of the great small town bars/cafes along the town’s railroad corridors, and then travel on old U.S. 10 (the town’s Main Street) on to Manhattan, Logan, and Three Forks before popping up on US 287 and continuing to home in Helena.

From 1983-85 Belgrade became one of my favorite Northern Pacific railroad towns. Often I would leave the interstate here, stop at truly one of the great small town bars/cafes along the town’s railroad corridors, and then travel on old U.S. 10 (the town’s Main Street) on to Manhattan, Logan, and Three Forks before popping up on US 287 and continuing to home in Helena.

Despite the boom, several landmarks remain. The Belgrade Community Church, built in 1904 as the town’s Presbyterian church, served in the 1980s as a joint church building for both the town’s Presbyterians and Baptists. This impressive Gothic Revival building had received several updates and additions in the mid-1970s. It became the Community Church in 1992 as the Presbyterians left and the American Baptist Church took over sole control of this historic church building.

Despite the boom, several landmarks remain. The Belgrade Community Church, built in 1904 as the town’s Presbyterian church, served in the 1980s as a joint church building for both the town’s Presbyterians and Baptists. This impressive Gothic Revival building had received several updates and additions in the mid-1970s. It became the Community Church in 1992 as the Presbyterians left and the American Baptist Church took over sole control of this historic church building.

Montana history has many episodes that involve rich eastern and foreign capitalists who rolled the dice on Montana’s resources. Typically everyone thinks of the mining and railroad corporations of the late 19th century. But in several places across the Big Sky Country, investors looked to the land itself and dreamed of agricultural bonanzas.

Montana history has many episodes that involve rich eastern and foreign capitalists who rolled the dice on Montana’s resources. Typically everyone thinks of the mining and railroad corporations of the late 19th century. But in several places across the Big Sky Country, investors looked to the land itself and dreamed of agricultural bonanzas. Such is the case of Amsterdam and Church Hill (now Churchill), two rural communities in today’s rapidly suburbanizing Gallatin County. The Manhattan Malting Company was mostly a New York City venture which in the early 1890s, before the terrible depression of 1893-1896, established an industrial base on the Northern Pacific Railroad, changing the name of the town from Moreland to Manhattan. The company purchased 13,000 acres,and acquired the best in agricultural technology, the Jacob Price Field Locomotive steam plow, to till the soil. They also convinced hundred of Dutch farmers to come to Gallatin County and work the land. Even with the hard times, or perhaps because of them, people still wanted good beer, and the company prospered. By 1905 the company decided to shed itself of the land and focus on malting barley.

Such is the case of Amsterdam and Church Hill (now Churchill), two rural communities in today’s rapidly suburbanizing Gallatin County. The Manhattan Malting Company was mostly a New York City venture which in the early 1890s, before the terrible depression of 1893-1896, established an industrial base on the Northern Pacific Railroad, changing the name of the town from Moreland to Manhattan. The company purchased 13,000 acres,and acquired the best in agricultural technology, the Jacob Price Field Locomotive steam plow, to till the soil. They also convinced hundred of Dutch farmers to come to Gallatin County and work the land. Even with the hard times, or perhaps because of them, people still wanted good beer, and the company prospered. By 1905 the company decided to shed itself of the land and focus on malting barley. The new land company focused on getting farmers on its land, and to secure a railroad spur line. The railroad came in 1911, and the community name of Amsterdam reflected the ethnic origins of the surrounding farmers and ranchers. Even when the Malting Company failed during Prohibition, the farmers kept going, developing some of the still most productive farmland in the state.

The new land company focused on getting farmers on its land, and to secure a railroad spur line. The railroad came in 1911, and the community name of Amsterdam reflected the ethnic origins of the surrounding farmers and ranchers. Even when the Malting Company failed during Prohibition, the farmers kept going, developing some of the still most productive farmland in the state. When I visited Amsterdam in 1984 the railroad line still operated but the spur closed the next year, leaving today only a faint corridor to mark its route. Look close and you can still see the outline of the T-plan town that was once “downtown Amsterdam” by the remaining historic commercial buildings, with the Danhof automobile dealership still in business today, with a newer showroom just east of the old railroad tracks.

When I visited Amsterdam in 1984 the railroad line still operated but the spur closed the next year, leaving today only a faint corridor to mark its route. Look close and you can still see the outline of the T-plan town that was once “downtown Amsterdam” by the remaining historic commercial buildings, with the Danhof automobile dealership still in business today, with a newer showroom just east of the old railroad tracks.

U.S. Highway 89 enters the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on its southern border, heading for its junction with U.S. Highway 2 and the reservation center of Browning. Before the junction, you cross the historic Two Medicine River, a historic corridor for the Blackfeet. To the west of the river crossing is a highway historical marker for Coldfeet School, a one-

U.S. Highway 89 enters the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on its southern border, heading for its junction with U.S. Highway 2 and the reservation center of Browning. Before the junction, you cross the historic Two Medicine River, a historic corridor for the Blackfeet. To the west of the river crossing is a highway historical marker for Coldfeet School, a one- room school (not extant) built for Blackfeet children in 1933 during the New Deal. To the east of the highway river crossing, however, was one of the earliest schools (1889) on the reservation, the Holy Family Catholic

room school (not extant) built for Blackfeet children in 1933 during the New Deal. To the east of the highway river crossing, however, was one of the earliest schools (1889) on the reservation, the Holy Family Catholic

This panorama of the mission site today shows that neither of the dormitories remain, although the historic frame barn and mill still stand (to the left) while the chapel is still a dominating element, and has been incorporated into present-day Blackfeet culture. It is in excellent shape.

This panorama of the mission site today shows that neither of the dormitories remain, although the historic frame barn and mill still stand (to the left) while the chapel is still a dominating element, and has been incorporated into present-day Blackfeet culture. It is in excellent shape. Another change is that the Blackfeet provide public interpretation of the site, through their own historical markers, which is extended into the adjacent historic cemetery, one of the most somber places in the region. The old mission is now part of the reservation’s heritage tourism effort.

Another change is that the Blackfeet provide public interpretation of the site, through their own historical markers, which is extended into the adjacent historic cemetery, one of the most somber places in the region. The old mission is now part of the reservation’s heritage tourism effort.

Returning to U.S. 89 and heading northwest, you head to the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and the town of Browning. The town is a center for reservation education, as shown by the new campus for the Blackfeet Community College.

Returning to U.S. 89 and heading northwest, you head to the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and the town of Browning. The town is a center for reservation education, as shown by the new campus for the Blackfeet Community College. Here too is another historic Catholic Church, the Little Flower Catholic Church, built in 1931, from locally available stone in a Gothic Revival style. The congregation supports a small Catholic school next door.

Here too is another historic Catholic Church, the Little Flower Catholic Church, built in 1931, from locally available stone in a Gothic Revival style. The congregation supports a small Catholic school next door. The Browning fairgrounds is an important Blackfeet recreation and cultural center, with this recent installation again providing public interpretation of Blackfeet culture.

The Browning fairgrounds is an important Blackfeet recreation and cultural center, with this recent installation again providing public interpretation of Blackfeet culture.

and U.S. 89, heading north. It created an appropriate, respectful way for the increasing number of auto tourists headed to Glacier National Park to learn about the Blackfeet in particular and Plains Indian culture in general. The famous mid-20th century anthropologist, John Ewers, had worked tribes to create the museum’s initial exhibits and collections. In the 21st century, the Blackfeet have developed additional institutions to take advantage of tourism through the nearby Glacier Peaks casino and hotel, a complex that has developed from 2011 to 2015.

and U.S. 89, heading north. It created an appropriate, respectful way for the increasing number of auto tourists headed to Glacier National Park to learn about the Blackfeet in particular and Plains Indian culture in general. The famous mid-20th century anthropologist, John Ewers, had worked tribes to create the museum’s initial exhibits and collections. In the 21st century, the Blackfeet have developed additional institutions to take advantage of tourism through the nearby Glacier Peaks casino and hotel, a complex that has developed from 2011 to 2015. These new buildings are part of a long-term continuum of tourism in Browning, starting with this old concrete tipi, built originally as a gas station in 1934 and now converted into a coffee shop. And the Blackfeet

These new buildings are part of a long-term continuum of tourism in Browning, starting with this old concrete tipi, built originally as a gas station in 1934 and now converted into a coffee shop. And the Blackfeet

Trading Post is a business found in all sorts of national park gateways–the classic place to get cheap souvenirs and t-shirts of all types, not to mention moccasins and all of the stereotypical material culture of Native American tourism in our country.

Trading Post is a business found in all sorts of national park gateways–the classic place to get cheap souvenirs and t-shirts of all types, not to mention moccasins and all of the stereotypical material culture of Native American tourism in our country.

the primary voice on what the park means, and how visitors can think about it today. The Native American presence on U.S. Highway 89 today is much more evident, with much more public interpretation, than in my travels 30 years ago.

the primary voice on what the park means, and how visitors can think about it today. The Native American presence on U.S. Highway 89 today is much more evident, with much more public interpretation, than in my travels 30 years ago. The two lanes of U.S. Highway 89 as it winds northwest from Choteau to the southern boundary of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, cross a stark yet compelling landscape, a jaunt that has never ceased to amaze me. To those only with the mountains of Glacier National Park in their minds will see merely open land, irrigated fields, scattered ranches.

The two lanes of U.S. Highway 89 as it winds northwest from Choteau to the southern boundary of the Blackfeet Indian Reservation, cross a stark yet compelling landscape, a jaunt that has never ceased to amaze me. To those only with the mountains of Glacier National Park in their minds will see merely open land, irrigated fields, scattered ranches. But there’s a deeper landscape here, some embodied in the tiny towns along the way, others in places just ignored, certainly not recognized. In the first post of 2016, and the 200th of this series of explorations of the Montana landscape, let’s once again look a bit harder.

But there’s a deeper landscape here, some embodied in the tiny towns along the way, others in places just ignored, certainly not recognized. In the first post of 2016, and the 200th of this series of explorations of the Montana landscape, let’s once again look a bit harder. For one, this is a landscape shaped by Cold War America. Nuclear missile silos were installed throughout the region with some easily accessible from the roadway. You wonder how many tourists realize that.

For one, this is a landscape shaped by Cold War America. Nuclear missile silos were installed throughout the region with some easily accessible from the roadway. You wonder how many tourists realize that. The federal imprint has lingered on this land for almost 150 years. Today north of Choteau this highway historical marker, and a lonely boulder set square in the adjacent field, mark the first federal intrusion, the creation of the Teton River Agency, where in 1868-69 the federal government established its reservation headquarters for the Blackfeet Indians. The agency was only here for about 7 years but this spot was where the first white-administered schools for Blackfeet children began, in 1872.

The federal imprint has lingered on this land for almost 150 years. Today north of Choteau this highway historical marker, and a lonely boulder set square in the adjacent field, mark the first federal intrusion, the creation of the Teton River Agency, where in 1868-69 the federal government established its reservation headquarters for the Blackfeet Indians. The agency was only here for about 7 years but this spot was where the first white-administered schools for Blackfeet children began, in 1872. Irrigation systems would be a third federal imprint on the landscape and it came early to this region–through the Reclamation Service’s Valier Irrigation Project–but to find that place you need to venture a bit east of U.S. 89 to the town of Valier, on the banks of Lake Frances, which was created as a reservoir for the irrigation project.

Irrigation systems would be a third federal imprint on the landscape and it came early to this region–through the Reclamation Service’s Valier Irrigation Project–but to find that place you need to venture a bit east of U.S. 89 to the town of Valier, on the banks of Lake Frances, which was created as a reservoir for the irrigation project. Valier has never been a very big place, but its investors in 1908, including William S. Cargill of the powerful Cargill family of Wisconsin (today’s Cargill Industries), had high hopes that the engineered landscape could create a ranching and farming wonderland.

Valier has never been a very big place, but its investors in 1908, including William S. Cargill of the powerful Cargill family of Wisconsin (today’s Cargill Industries), had high hopes that the engineered landscape could create a ranching and farming wonderland.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the school remains in use today, as a bed and breakfast establishment. Even though Valier never reached the dreams of the Cargills and other outside investors, it has been a stable agricultural community for 100 years–the population today is only 100 less than what the census takers marked in 1920. Valier has that

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the school remains in use today, as a bed and breakfast establishment. Even though Valier never reached the dreams of the Cargills and other outside investors, it has been a stable agricultural community for 100 years–the population today is only 100 less than what the census takers marked in 1920. Valier has that

Heritage tourism also remains alive along U.S. Highway 89, and for those travelers who slow just a bit there is now the Two Medicine Dinosaur Center at Bynum.

Heritage tourism also remains alive along U.S. Highway 89, and for those travelers who slow just a bit there is now the Two Medicine Dinosaur Center at Bynum.

One of my favorite county seats is Choteau, where U.S. Highways 89 and 287 meet. Both of those roads were and are among my favorite to take in the state, and Choteau I quickly found had one of my favorite local dives the Wagon Wheel. Back in the day, however, I did not appreciate how the town’s history and built environment was shaped by the Sun River Irrigation project and the overall growth in the county during the first two decades of the 20th century and later a second boom in the 1940s.

One of my favorite county seats is Choteau, where U.S. Highways 89 and 287 meet. Both of those roads were and are among my favorite to take in the state, and Choteau I quickly found had one of my favorite local dives the Wagon Wheel. Back in the day, however, I did not appreciate how the town’s history and built environment was shaped by the Sun River Irrigation project and the overall growth in the county during the first two decades of the 20th century and later a second boom in the 1940s. Choteau has a different look than most towns from this era of Montana history. The centerpiece of the towns plan is not a railroad depot but the magnificent Teton County Courthouse (1906), which occupies a spot where the two federal highways junction. Designed by architects Joseph B. Gibson and George H. Shanley, the National Register-listed courthouse is made of locally quarried stone in a late interpretation of Richardsonian Romanesque style, similar to, but to a much lesser scale and detail, than H. H. Richardson’s own Allegheny County Courthouse (c. 1886) in Pittsburgh.

Choteau has a different look than most towns from this era of Montana history. The centerpiece of the towns plan is not a railroad depot but the magnificent Teton County Courthouse (1906), which occupies a spot where the two federal highways junction. Designed by architects Joseph B. Gibson and George H. Shanley, the National Register-listed courthouse is made of locally quarried stone in a late interpretation of Richardsonian Romanesque style, similar to, but to a much lesser scale and detail, than H. H. Richardson’s own Allegheny County Courthouse (c. 1886) in Pittsburgh.

This historic neoclassical-styled bank building is now home to a coffee shop but other commercial buildings have changed very little, except for the mix of retail business. This is not a dying business district but one with a good bit of jump, of vitality.

This historic neoclassical-styled bank building is now home to a coffee shop but other commercial buildings have changed very little, except for the mix of retail business. This is not a dying business district but one with a good bit of jump, of vitality.

where the historic Bella Vista Motel–a perfect example of a 1950s motel with separate units like tiny Ranch-styled houses–has given way to a c. 2015 conversion into apartments.

where the historic Bella Vista Motel–a perfect example of a 1950s motel with separate units like tiny Ranch-styled houses–has given way to a c. 2015 conversion into apartments.

We just finished an exploration of U.S. Highway south from Great Falls to Livingston, the gateway to Yellowstone National Park. Now let’s head in the opposite direction, north of Great Falls to Glacier National Park. In the first half of this trek, one great man-made landscape dominates either side of the road–the Sun River Irrigation Project, established by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 1906 but not completed until the late 1920s.

We just finished an exploration of U.S. Highway south from Great Falls to Livingston, the gateway to Yellowstone National Park. Now let’s head in the opposite direction, north of Great Falls to Glacier National Park. In the first half of this trek, one great man-made landscape dominates either side of the road–the Sun River Irrigation Project, established by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in 1906 but not completed until the late 1920s.

Feeding in and out of Fairfield are multiple canals and ditches, with the great bulk of land devoted to the production of malting barley, under

Feeding in and out of Fairfield are multiple canals and ditches, with the great bulk of land devoted to the production of malting barley, under

Fairfield itself is a classic T-plan railroad town. The barley granaries dominate the trackside, where also is located the headquarters for the Greenfields Irrigation District, so designated in 1926.

Fairfield itself is a classic T-plan railroad town. The barley granaries dominate the trackside, where also is located the headquarters for the Greenfields Irrigation District, so designated in 1926. Along the stem of the “T” plan are all of the primary commercial buildings of the town, from an unassuming log visitor center to various one-story commercial buildings, and, naturally, a classic bar, the Silver Dollar.

Along the stem of the “T” plan are all of the primary commercial buildings of the town, from an unassuming log visitor center to various one-story commercial buildings, and, naturally, a classic bar, the Silver Dollar.

Public spaces and institutions are located at the bottom of the “T,” including a community park and swimming pool, a c. 1960 community hall, and an Art-Deco styled Fairfield High School. The park, pool, and high school were all part of the second period of federal improvement at Fairfield during the New Deal era.

Public spaces and institutions are located at the bottom of the “T,” including a community park and swimming pool, a c. 1960 community hall, and an Art-Deco styled Fairfield High School. The park, pool, and high school were all part of the second period of federal improvement at Fairfield during the New Deal era.

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention.

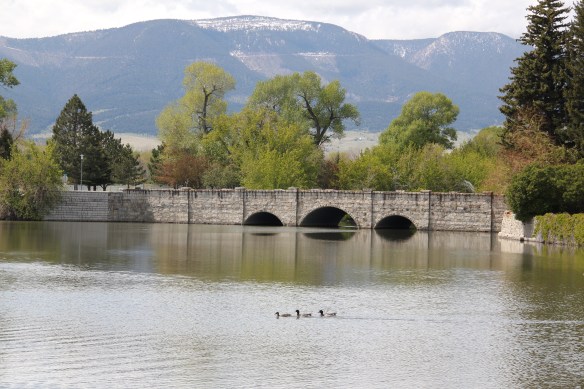

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention. Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community. Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Livingston was one of the Northern Pacific Railroad’s most important division points. Not only did the massive and architecturally ornate passenger station, discussed in the previous blog, serve as a gateway to Yellowstone National Park, it contained various company offices, serving as a nerve center for the thousands of miles of railroad line. If you do the typical tourist thing in Livingston, you pay attention to the depot and the many late 19th and early 20th century buildings south of the tracks.

Livingston was one of the Northern Pacific Railroad’s most important division points. Not only did the massive and architecturally ornate passenger station, discussed in the previous blog, serve as a gateway to Yellowstone National Park, it contained various company offices, serving as a nerve center for the thousands of miles of railroad line. If you do the typical tourist thing in Livingston, you pay attention to the depot and the many late 19th and early 20th century buildings south of the tracks. But to find where the real work of the railroad took place, you have to locate the underpass that takes you to the north side of the tracks, and the extensive Northern Pacific railroad shops. This area is not as busy as it once was, but enough buildings remain and enough activity takes place 24-7 that you quickly grasp that here is the heartbeat of the line. In the photo above, one early shop building, the lighter color brick building to the right center, still stands. Most others date to the line’s diesel conversion in the mid-20th century.

But to find where the real work of the railroad took place, you have to locate the underpass that takes you to the north side of the tracks, and the extensive Northern Pacific railroad shops. This area is not as busy as it once was, but enough buildings remain and enough activity takes place 24-7 that you quickly grasp that here is the heartbeat of the line. In the photo above, one early shop building, the lighter color brick building to the right center, still stands. Most others date to the line’s diesel conversion in the mid-20th century. With the mountains to the south, and the outlines of the town visible as well, the shops are impressive statements of corporate power and determination, and how railroads gave an industrial cast to the landscape.

With the mountains to the south, and the outlines of the town visible as well, the shops are impressive statements of corporate power and determination, and how railroads gave an industrial cast to the landscape. The north side, in many ways, was a separate world. Here the homes may date to the Victorian era too, but they are not the stylish period interpretations found in numbers on the south side. Rather they are vernacular styled cottages, or unadorned homes typical of America’s turn-of-the-century working class.

The north side, in many ways, was a separate world. Here the homes may date to the Victorian era too, but they are not the stylish period interpretations found in numbers on the south side. Rather they are vernacular styled cottages, or unadorned homes typical of America’s turn-of-the-century working class.

The school was converted into a community museum some 30 years ago, and if you visit the grand passenger station, you also need to stop at the school, to get a fuller picture of Livingston, the railroad town.

The school was converted into a community museum some 30 years ago, and if you visit the grand passenger station, you also need to stop at the school, to get a fuller picture of Livingston, the railroad town.

The above block of commercial businesses was once better known as the Montana Hotel while the block below, called the Hiatt Hotel in more recent years, was the Park Hotel, opened in 1904 to take advantage of increased tourist business due to the new Northern Pacific depot. Noted Montana architect C.S. Haire was the designer.

The above block of commercial businesses was once better known as the Montana Hotel while the block below, called the Hiatt Hotel in more recent years, was the Park Hotel, opened in 1904 to take advantage of increased tourist business due to the new Northern Pacific depot. Noted Montana architect C.S. Haire was the designer. These buildings served tourists in the summer months but throughout the years they relied on the “drummer” trade. Drummers were a word used to describe traveling businessmen, who rode the rails constantly, stopping at towns large and small, to drum up business for their companies. They too, like the machine shop workers on the south side, were a constant presence on the railroad lines of 100 years ago, and helped to make the lines hum with their travel and their stories.

These buildings served tourists in the summer months but throughout the years they relied on the “drummer” trade. Drummers were a word used to describe traveling businessmen, who rode the rails constantly, stopping at towns large and small, to drum up business for their companies. They too, like the machine shop workers on the south side, were a constant presence on the railroad lines of 100 years ago, and helped to make the lines hum with their travel and their stories.