In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country.

I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

Motels along U.S. Highway 2 often had the grand statement to catch attention of those traveling at 80 miles a hour down the highway. Galata, which billed itself as a gateway to the Whitlash port of entry on the Canadian border to the north, had the tallest cowboy in the region to greet visitors.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

The Circle Inn Motel outside of Havre on U.S. Highway 2 reflected the classic design of separate duplexes–cabins–for guests while the gleaming white horse statue reminded them, if they needed the prod, that they were in the wild west.

Similar mid-20th century motels are found along Montana’s historic federal highways. Some, like the La Hood Motel, are now forgotten as the highway, once known as the Yellowstone Trail and then U.S. Highway 10, has been relegated to secondary use.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century.

Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Other motels have carried on, in a diminished role, dependent more on workers needing temporary quarters than on travelers. In Malta, on U.S. Highway 2, I expected easy to acquire and cheap lodging at the Maltana Motel–a favorite of mine from the 1980s–but even though the town was over 200 miles from Williston, North Dakota, demands for its rooms had risen with the oil boom of the early 2010s.

The Country Side Inn Motel in Harlowton once buzzed with travelers along either U.S. Highway 12 or U.S. Highway 191 but as interstate routes have become so dominant, these motels have struggled to attract customers.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered.

The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

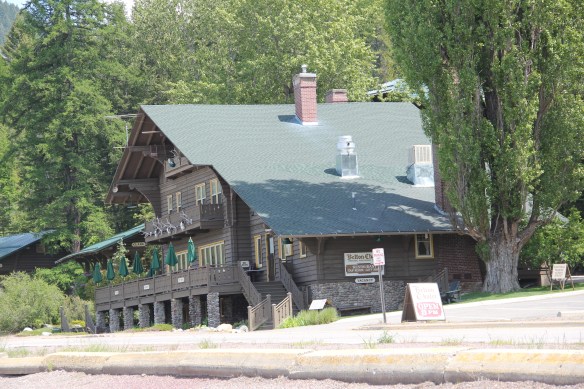

I began this brief overview with the first place I stayed during the 1984-1985 fieldwork, and I will close with the last place I stayed as I finished the new statewide survey in May 2016: the Yodeler Inn in Red Lodge. Built in 1964 this wonder chalet-style property is listed in the National Register–of course in 1984 I never gave a thought about the motel as National Register worthy, I just loved the location, and thought it was cool.

It is still that–good rooms, great lobby, and a self-proclaimed “groovy” place. To the north of the historic downtown are all of the chains you might want–stay there if you must, and leave the Yodeler Motel to me!

I am speaking instead of the wide range of images and themes that visually interpret the town’s and county’s history. Finding public art murals about the open landscape once dominated by the Blackfeet Indians and the buffalo is not surprising–communities often embrace the deep history of their land.

I am speaking instead of the wide range of images and themes that visually interpret the town’s and county’s history. Finding public art murals about the open landscape once dominated by the Blackfeet Indians and the buffalo is not surprising–communities often embrace the deep history of their land. That Cut Bank also has a large expressive mural about the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not surprising–murals about Lewis and Clark were installed across several towns during the bicentennial of the expedition in the first decade of this century. East of Cut Bank is Camp Disappointment, one of the more important sites associated with the Corps of Discovery.

That Cut Bank also has a large expressive mural about the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not surprising–murals about Lewis and Clark were installed across several towns during the bicentennial of the expedition in the first decade of this century. East of Cut Bank is Camp Disappointment, one of the more important sites associated with the Corps of Discovery. Nor is it surprising to see communities commemorate their homesteading roots, and the importance of agriculture and cattle ranching.

Nor is it surprising to see communities commemorate their homesteading roots, and the importance of agriculture and cattle ranching.

But I was surprised, pleasantly, by the number of murals that also documented the town’s twentieth century history, whether it is the magnificent steel trestle of the Great Northern Railway just west of the commercial core, or a mural that reminded everyone of the days when the railroad dominated all traffic here.

But I was surprised, pleasantly, by the number of murals that also documented the town’s twentieth century history, whether it is the magnificent steel trestle of the Great Northern Railway just west of the commercial core, or a mural that reminded everyone of the days when the railroad dominated all traffic here.

It is this first half of the 20th century feel that the murals interpret–the era that actually built most of the historic buildings you find there today–that I find so impressive and memorable about Cut Bank, be it people on bicycles or what an old service station was like.

It is this first half of the 20th century feel that the murals interpret–the era that actually built most of the historic buildings you find there today–that I find so impressive and memorable about Cut Bank, be it people on bicycles or what an old service station was like.

Space matters when you interpret the built environment, and these various murals reflect not only a sense of town pride and identity they also give meaning to buildings and stories long forgotten.

Space matters when you interpret the built environment, and these various murals reflect not only a sense of town pride and identity they also give meaning to buildings and stories long forgotten.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

The answer was yes, to both questions. Here is an early 20th century log building landmark on a highway where the traffic seems to never end. It is also along the corridor of a new recreational system–the Great Northern Rails to Trails linear park that uses an old railroad corridor to connect the city to the country in Flathead County.

The answer was yes, to both questions. Here is an early 20th century log building landmark on a highway where the traffic seems to never end. It is also along the corridor of a new recreational system–the Great Northern Rails to Trails linear park that uses an old railroad corridor to connect the city to the country in Flathead County.

The trail allows bikers to see the rural landscape, still dotted with family farms, of the Smith Valley as it stretches west to Kila, where the old Cottage Inn has been converted in the last few years into the Kila Pub, complete with the Arts and Crafts/Tudor theme associated with the railroad corridor.

The trail allows bikers to see the rural landscape, still dotted with family farms, of the Smith Valley as it stretches west to Kila, where the old Cottage Inn has been converted in the last few years into the Kila Pub, complete with the Arts and Crafts/Tudor theme associated with the railroad corridor.

To the north of Kalispell and Whitefish U.S. Highway 93 takes you past the ski developments into a thick forested area, managed in part as the Stillwater State Forest.

To the north of Kalispell and Whitefish U.S. Highway 93 takes you past the ski developments into a thick forested area, managed in part as the Stillwater State Forest.

from the 1920s into the 1960s. While several are from the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s, state ranger Pete De Groat built his log residence in 1928 in the Rustic Style. Stillwater was Montana’s first state forest.

from the 1920s into the 1960s. While several are from the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s, state ranger Pete De Groat built his log residence in 1928 in the Rustic Style. Stillwater was Montana’s first state forest.

I love Montana town signs, and Troy, deep in the state’s logging country, has one of the best. The sign lures to a city park nestled along the Kootenai River. The focus point is a

I love Montana town signs, and Troy, deep in the state’s logging country, has one of the best. The sign lures to a city park nestled along the Kootenai River. The focus point is a

the Great Northern’s main line, and I documented the few historic buildings left facing the railroad tracks today. The Home Bar (c. 1914) and the Club Bar were institutions then, and remain so today. The Kootenai State Bank building still stands but has experienced a major change to its facade–made better in part by the American flag painted over some of the frame addition.

the Great Northern’s main line, and I documented the few historic buildings left facing the railroad tracks today. The Home Bar (c. 1914) and the Club Bar were institutions then, and remain so today. The Kootenai State Bank building still stands but has experienced a major change to its facade–made better in part by the American flag painted over some of the frame addition. The Troy Jail, above, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and it remains the only building so listed in the town today. D.E. Crissey, a local contractor, built it out of concrete in 1924 during Troy’s boom from 1916 to 1926 when its population jumped from 300 to 1300. The Snowstorm mine, which produced lead, zinc, and silver, started to serve the demand for raw materials during World War I. The mine soon turned what had been a small railroad town into a mining camp best known for its brothels and bars. Then in the early 1920s the Great Northern decided to build a division point here, further booming the town. The Sandpoint Pole and Lumber Company began its logging business in 1923, and Troy suddenly was the largest town in the county

The Troy Jail, above, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and it remains the only building so listed in the town today. D.E. Crissey, a local contractor, built it out of concrete in 1924 during Troy’s boom from 1916 to 1926 when its population jumped from 300 to 1300. The Snowstorm mine, which produced lead, zinc, and silver, started to serve the demand for raw materials during World War I. The mine soon turned what had been a small railroad town into a mining camp best known for its brothels and bars. Then in the early 1920s the Great Northern decided to build a division point here, further booming the town. The Sandpoint Pole and Lumber Company began its logging business in 1923, and Troy suddenly was the largest town in the county

U.S. Highway 2 enters northwest Montana in Lincoln County and from there the federal highway stretches eastward through the towns of Troy and Libby with vast rural stretches along the way to Kalispell. Paralleling the highway is the historic route of the Great Northern Railway, which brought timber and mining industries to this corner of Montana.

U.S. Highway 2 enters northwest Montana in Lincoln County and from there the federal highway stretches eastward through the towns of Troy and Libby with vast rural stretches along the way to Kalispell. Paralleling the highway is the historic route of the Great Northern Railway, which brought timber and mining industries to this corner of Montana. Before you encounter the towns, however, there is a spot that is among my favorite in the state, and a place that I discussed in some depth in the book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History: Kootenai Falls.

Before you encounter the towns, however, there is a spot that is among my favorite in the state, and a place that I discussed in some depth in the book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History: Kootenai Falls.

The falls is spectacular, no matter what time of the year you visit. But do stop and consider the mountains and bluffs that surround it. The entire landscape is what mattered to the Native Americans as they navigated through the area, or took vision quests at isolated places, or stopped to fish along the banks or hunt the wild game who also came to the falls for nourishment.

The falls is spectacular, no matter what time of the year you visit. But do stop and consider the mountains and bluffs that surround it. The entire landscape is what mattered to the Native Americans as they navigated through the area, or took vision quests at isolated places, or stopped to fish along the banks or hunt the wild game who also came to the falls for nourishment. There are few less untouched places than Kootenai Falls. The county park provides access and information. It is then up to you to explore, stop, and think about how humans have interacted with this places, taking aways thoughts and messages that we can only guess at, for thousands of years.

There are few less untouched places than Kootenai Falls. The county park provides access and information. It is then up to you to explore, stop, and think about how humans have interacted with this places, taking aways thoughts and messages that we can only guess at, for thousands of years. U.S. Highway 89 enters the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on its southern border, heading for its junction with U.S. Highway 2 and the reservation center of Browning. Before the junction, you cross the historic Two Medicine River, a historic corridor for the Blackfeet. To the west of the river crossing is a highway historical marker for Coldfeet School, a one-

U.S. Highway 89 enters the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on its southern border, heading for its junction with U.S. Highway 2 and the reservation center of Browning. Before the junction, you cross the historic Two Medicine River, a historic corridor for the Blackfeet. To the west of the river crossing is a highway historical marker for Coldfeet School, a one- room school (not extant) built for Blackfeet children in 1933 during the New Deal. To the east of the highway river crossing, however, was one of the earliest schools (1889) on the reservation, the Holy Family Catholic

room school (not extant) built for Blackfeet children in 1933 during the New Deal. To the east of the highway river crossing, however, was one of the earliest schools (1889) on the reservation, the Holy Family Catholic

This panorama of the mission site today shows that neither of the dormitories remain, although the historic frame barn and mill still stand (to the left) while the chapel is still a dominating element, and has been incorporated into present-day Blackfeet culture. It is in excellent shape.

This panorama of the mission site today shows that neither of the dormitories remain, although the historic frame barn and mill still stand (to the left) while the chapel is still a dominating element, and has been incorporated into present-day Blackfeet culture. It is in excellent shape. Another change is that the Blackfeet provide public interpretation of the site, through their own historical markers, which is extended into the adjacent historic cemetery, one of the most somber places in the region. The old mission is now part of the reservation’s heritage tourism effort.

Another change is that the Blackfeet provide public interpretation of the site, through their own historical markers, which is extended into the adjacent historic cemetery, one of the most somber places in the region. The old mission is now part of the reservation’s heritage tourism effort.

Returning to U.S. 89 and heading northwest, you head to the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and the town of Browning. The town is a center for reservation education, as shown by the new campus for the Blackfeet Community College.

Returning to U.S. 89 and heading northwest, you head to the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and the town of Browning. The town is a center for reservation education, as shown by the new campus for the Blackfeet Community College. Here too is another historic Catholic Church, the Little Flower Catholic Church, built in 1931, from locally available stone in a Gothic Revival style. The congregation supports a small Catholic school next door.

Here too is another historic Catholic Church, the Little Flower Catholic Church, built in 1931, from locally available stone in a Gothic Revival style. The congregation supports a small Catholic school next door. The Browning fairgrounds is an important Blackfeet recreation and cultural center, with this recent installation again providing public interpretation of Blackfeet culture.

The Browning fairgrounds is an important Blackfeet recreation and cultural center, with this recent installation again providing public interpretation of Blackfeet culture.

and U.S. 89, heading north. It created an appropriate, respectful way for the increasing number of auto tourists headed to Glacier National Park to learn about the Blackfeet in particular and Plains Indian culture in general. The famous mid-20th century anthropologist, John Ewers, had worked tribes to create the museum’s initial exhibits and collections. In the 21st century, the Blackfeet have developed additional institutions to take advantage of tourism through the nearby Glacier Peaks casino and hotel, a complex that has developed from 2011 to 2015.

and U.S. 89, heading north. It created an appropriate, respectful way for the increasing number of auto tourists headed to Glacier National Park to learn about the Blackfeet in particular and Plains Indian culture in general. The famous mid-20th century anthropologist, John Ewers, had worked tribes to create the museum’s initial exhibits and collections. In the 21st century, the Blackfeet have developed additional institutions to take advantage of tourism through the nearby Glacier Peaks casino and hotel, a complex that has developed from 2011 to 2015. These new buildings are part of a long-term continuum of tourism in Browning, starting with this old concrete tipi, built originally as a gas station in 1934 and now converted into a coffee shop. And the Blackfeet

These new buildings are part of a long-term continuum of tourism in Browning, starting with this old concrete tipi, built originally as a gas station in 1934 and now converted into a coffee shop. And the Blackfeet

Trading Post is a business found in all sorts of national park gateways–the classic place to get cheap souvenirs and t-shirts of all types, not to mention moccasins and all of the stereotypical material culture of Native American tourism in our country.

Trading Post is a business found in all sorts of national park gateways–the classic place to get cheap souvenirs and t-shirts of all types, not to mention moccasins and all of the stereotypical material culture of Native American tourism in our country.

the primary voice on what the park means, and how visitors can think about it today. The Native American presence on U.S. Highway 89 today is much more evident, with much more public interpretation, than in my travels 30 years ago.

the primary voice on what the park means, and how visitors can think about it today. The Native American presence on U.S. Highway 89 today is much more evident, with much more public interpretation, than in my travels 30 years ago.