Hinsdale (just over 200 people in Valley County) and Saco (just under 200 people in Phillips County) are two country towns along the Hi-Line between the much larger county seats of Glasgow and Malta. I have little doubt that few visitors ever stop, or even slow down much, as they speed along the highway. Both towns developed as railroad stops along the Great Northern Railway–the image above shows how close the highway and railroad tracks are along this section of the Hi-Line. Both largely served, and still

serve, historic ranches, such as the Robinson Ranch, established in 1891, in Phillips County. Both towns however have interesting buildings, and as long as they keep their community schools, both will survive in the future.

Hinsdale School, Valley County

Saco School, Phillips County

Of the two towns, I have discussed Saco to a far greater extent in this blog because it was one of my “targeted” stops in the 1984 survey. The State Historic Preservation Office at the Montana Historical Society had received inquiries from local residents in Saco about historic preservation alternatives and I was there to take a lot of images to share back with the preservationists in Helena. But in my earlier posts, I neglected two community

buildings, the rather different design of the post office from the 1960s and the vernacular Gothic beauty of the historic Methodist Church, especially the Victorian brackets of its bell tower.

buildings, the rather different design of the post office from the 1960s and the vernacular Gothic beauty of the historic Methodist Church, especially the Victorian brackets of its bell tower.

I ignored Hinsdale almost totally in its first posting, focusing on roadside murals. This Valley County town is worth a second look, if just for its two historic bank buildings. The former First National Bank and the former Valley County Bank both speak to the hopes for growth along this section of the Milk River Project of the U.S. Reclamation Service in the early 20th century. Architecturally both buildings were touched by the Classical Revival style, and both took the “strongbox” form of bank buildings that you can find throughout the midwest and northern plains in the first two decades of the 20th century.

The rest of Hinsdale’s “commercial district” has the one-story “false-front” buildings often found in country railroad towns along the Hi-Line.

Local residents clearly demonstrate their sense of community not only through the school, which stands at the of the commercial area. But community pride also comes through in such buildings as the c. 1960s American Legion Hall, the c. 1902 Methodist church (the separated cupola must be a good story), and St. Anthony’s Catholic Church.

These small railroad towns of the Hi-Line have been losing population for decades, yet they remain, and the persistence of these community institutions helps to explain why.

The county library, above, is small but busy, a reminder of how important these public buildings can be. About 5 years ago, the time of my last visit, Scobey still had its own medical center, below, as well as a distinctive post office, different from many in the region due to its modernist style.

The county library, above, is small but busy, a reminder of how important these public buildings can be. About 5 years ago, the time of my last visit, Scobey still had its own medical center, below, as well as a distinctive post office, different from many in the region due to its modernist style.

But like most travelers I roar down the highway, perhaps noting the tall grain elevators facing the town proper, and pay little attention to anything else. In a post of four years ago, I spoke of Golden Valley County and its historic landmarks, highlighting the grain elevators, the Golden Valley Courthouse, the Sims-Garfield historic ranch, and the historic town bar in Ryegate. But like the other eastern Montana county seats, Ryegate deserves a closer look.

But like most travelers I roar down the highway, perhaps noting the tall grain elevators facing the town proper, and pay little attention to anything else. In a post of four years ago, I spoke of Golden Valley County and its historic landmarks, highlighting the grain elevators, the Golden Valley Courthouse, the Sims-Garfield historic ranch, and the historic town bar in Ryegate. But like the other eastern Montana county seats, Ryegate deserves a closer look.

Ryegate received one of the standardized “modern” post office designs from the federal government in the 1970s–the town’s fortunes have remained basically frozen after the Milwaukee Road declared bankruptcy and shut down the tracks in 1980.

Ryegate received one of the standardized “modern” post office designs from the federal government in the 1970s–the town’s fortunes have remained basically frozen after the Milwaukee Road declared bankruptcy and shut down the tracks in 1980.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors. Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

The town’s grain elevators really are its landmark–the town is along the railroad spur and sits off Montana Highway 16–without the elevators you might not even notice it.

The town’s grain elevators really are its landmark–the town is along the railroad spur and sits off Montana Highway 16–without the elevators you might not even notice it. Agriculture defines the use of the largest buildings of the town, and while it is a tiny place Reserve serves a much larger region of ranches located between Plentywood, the county seat, to the north and Medicine Lake, to the south.

Agriculture defines the use of the largest buildings of the town, and while it is a tiny place Reserve serves a much larger region of ranches located between Plentywood, the county seat, to the north and Medicine Lake, to the south. This larger audience for services in Reserve helps to explain the survival of the Reserve Post Office–so many tiny Montana towns have lost the one federal institution that had been there since the town’s beginning.

This larger audience for services in Reserve helps to explain the survival of the Reserve Post Office–so many tiny Montana towns have lost the one federal institution that had been there since the town’s beginning. But naturally I will urge you to make a stop, however brief, at the Reserve Bar. This concrete block building, with its period glass block windows, is a friendly place, and a great way to talk with both residents and surrounding farmers.

But naturally I will urge you to make a stop, however brief, at the Reserve Bar. This concrete block building, with its period glass block windows, is a friendly place, and a great way to talk with both residents and surrounding farmers.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

The dam is 422 feet tall and stretches across the river for 3,055 feet–well over a 1/2 mile. It creates a huge reservoir, extending 90 miles to the north and into British Columbia, among the ten largest reservoirs in the nation. And like that, a historic river valley became a recreational lake in a joint project between the United States and Canada.

The dam is 422 feet tall and stretches across the river for 3,055 feet–well over a 1/2 mile. It creates a huge reservoir, extending 90 miles to the north and into British Columbia, among the ten largest reservoirs in the nation. And like that, a historic river valley became a recreational lake in a joint project between the United States and Canada.

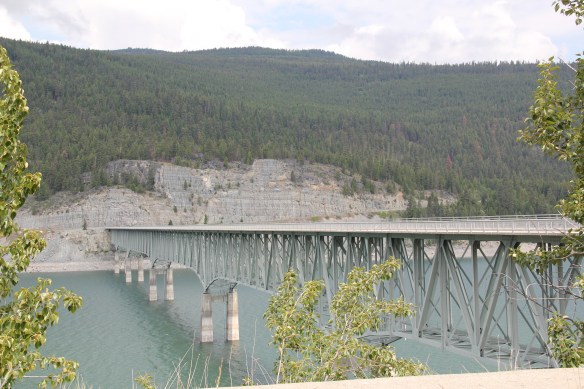

The Lake Koocanusa Bridge, which provides access to a Mennonite community and a backroad way to Yaak, is the state’s longest, and in many ways, its most spectacular multi-truss bridge. The bridge is 2,437 feet long, and stands, depending on water level, some 270 feet above the lake.

The Lake Koocanusa Bridge, which provides access to a Mennonite community and a backroad way to Yaak, is the state’s longest, and in many ways, its most spectacular multi-truss bridge. The bridge is 2,437 feet long, and stands, depending on water level, some 270 feet above the lake.

There was no interpretation at this bridge in 1984, but the scenic highway designation has led to the placement of overlooks and interpretive markers at some places along the lake. One wishes for the same at the Montana town that the lake displaced, Rexford. This once

There was no interpretation at this bridge in 1984, but the scenic highway designation has led to the placement of overlooks and interpretive markers at some places along the lake. One wishes for the same at the Montana town that the lake displaced, Rexford. This once small river town had to move, or be inundated. And since the move took place in the mid to late 1960s, the town embodies the mid-century modern aesthetic, both in the design of many buildings but also in the town plan itself as the federal government finished relocating Rexford in the early 1970s.

small river town had to move, or be inundated. And since the move took place in the mid to late 1960s, the town embodies the mid-century modern aesthetic, both in the design of many buildings but also in the town plan itself as the federal government finished relocating Rexford in the early 1970s.

school by itself is a fascinating statement of both design but also a community’s determination to stay, no matter what the federal government threw their way. Needless to say, in 1984 I paid Rexford no attention–nothing historic was there, it was all new. But now it is clear what a important place in Lincoln County’s 20th century history Rexford came to be.

school by itself is a fascinating statement of both design but also a community’s determination to stay, no matter what the federal government threw their way. Needless to say, in 1984 I paid Rexford no attention–nothing historic was there, it was all new. But now it is clear what a important place in Lincoln County’s 20th century history Rexford came to be. Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

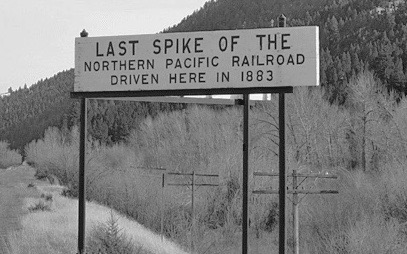

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters. The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory.

The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory. The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century.

The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century. Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history. Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses.

Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses. In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole. There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.

There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley.

Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley. At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93. And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

And the coffee is always hot, and strong. For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school. While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students.

While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students. Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.