Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

Professional staff and volunteers, all led by Ellen Crain, keep both the community and scholars engaged–the number of strong histories, public projects, and exhibits that have come, in whole or in part, from this place in the last 30 years is very impressive. Plus it is

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

Now an interpretive monument talks about the union, the bombing, and addresses directly a chilling chapter in the long struggle between labor and capital in Butte. Installed c. 1993 near the “top” of Main Street, this site sets the stage for the amount of public interpretation found in the city today.

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

interpretation efforts, it is also a place for community gatherings, such as the Montana Folklife Festival in recent years. It is important to note that the marker at the Original just doesn’t celebrate the technology it also notes how many men–43–died at that mine. The progress of Butte happened on the back of its working class miners.

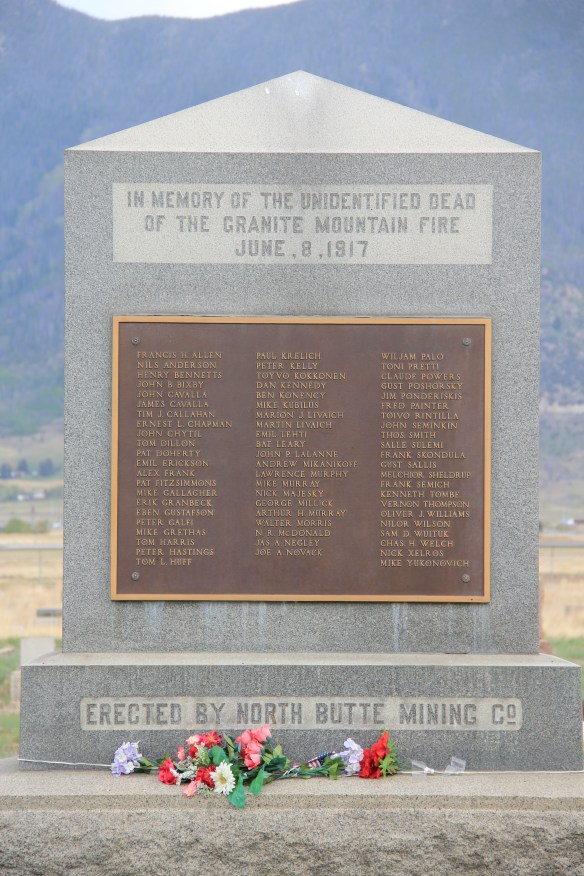

Here is another promising change: the willingness to landmark and discuss the human costs of mining. Butte’s most infamous event was the Granite Mountain/ Speculator Mine disaster of 1917 in which 168 miners died–still the single most deadly disaster in American hard-rock mining history. Not that the event was ignored at the time. In fact the North Butte mining company erected the memorial above to those who perished in Mountain View Cemetery, far from the scene, shortly thereafter. Who knew this memorial existed? There were no signs marking the way there–you had to search to find it.

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

ARCO, along with public partners, funded the site in this century, as part of the general Superfund cleanup of the mining district. But the park was long overdue as well as the recognition that some 2,500 miners lost their lives in the Butte district. The marker’s statement–“you are standing on hallowed ground”–is typically reserved for military parks. Within the context of Butte, however, it is totally justified, and an important point to remember wherever you are in the city.

The reality that Butte’s mines contributed significantly to American war efforts in the 20th century is recalled through a public art mural near a public transit stop. Public sculpture also interprets what was and what has been lost in Butte.

Through the efforts of the state historic preservation office, and its commendable program of providing interpretive markers for National Register properties, the residential side of Butte’s story is also being told. You have to love the “blue” house, associated with U.S. Senator Burton K. Wheeler, one of the New Deal era movers and shakers.

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the

interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot.

interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot.

The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

Then of course, designed for highway travelers and tourists, there is the now classic World Museum of Mining, established in 1965 around the Orphan Girl mine. The WMM lets rusting industrial artifacts convey part of the story while the existing mining buildings are open, allowing you to get a more physical experience of what the head frames and mines were really about. And, as typical of Montana museums of the 1960s and 1970s, there is the attached “frontier village,” interpreting what early Butte was all about. Don’t get me

wrong: there are many things to like about the WMM–it is rich in artifacts, as the miners items above suggest (and more about it in another post). But it is a controlled, sterile experience, and I would hate for that to be the only takeaway visitors have about Butte and its significance. The museum is away from uptown Butte, and visitors who stop here may never go explore the deeper story within the town and its historic neighborhoods.

Old Butte Historical Adventures on Main Street is just one group of heritage entrepreneurs who provide visitors with a “up close and personal” viewpoint and experience of Butte’s historic landscape. Walking tours of Uptown along with various special theme tours engage visitors and residents with local history in a way different from traditional monuments, markers, and historic sites.

But one must be aware that the pressure to commercialize can also distort, and demean, the significance of it all. What happens at the Dumas Hotel–a historic brothel–will be interesting to watch. The story of prostitution is very much part of the fabric of the city, but one that for many years people did not want to tell, except with snide references and a snicker or two. Let’s hope that changes as the Dumas is restored and opened as a heritage venue: addressing the sex trade and role of women and men accurately and in context would add immeasurably to the sense of authenticity, of realism, in the Butte story.

The most exciting part of Butte’s heritage development to my mind are the series of greenways or trails that link the mines to the business and residential districts and that link Butte to neighboring enclaves like Centerville (shown above). Recreational opportunity–walking, jogging, boarding, biking–is a huge component of livable spaces for the 21st century. When these trails are enhanced by the stories they touch or cover,

they become even more meaningful and valuable. If you have lived in Montana for 6 months or 60 years, it is time to return to Butte and take the Montana Copperway (trailhead shown above) –not only would it be good for your health, it also gives you a lasting perspective of a mining town within the vast Northern Rockies landscape, and how men and women from all sorts of backgrounds and nations established a real community, one that has outlasted the mines that first created it.

Then Senator Moss took me for a quick tour of its late 1990s renovation in 2007–its conversion into law offices respected both its original spaces and interior design.

Then Senator Moss took me for a quick tour of its late 1990s renovation in 2007–its conversion into law offices respected both its original spaces and interior design.

The district’s architectural jewel, the Dining Room, dates almost a generation later to 1926. Architect Gilbert S. Underwood designed one of the late marvels of the Rustic style as defined in the northern Rockies. With its rugged stone exterior rising as it was a natural formation in the land, the dining room immediately told arriving visitors that an adventure awaited them, especially once they stepped inside and experienced the vast log interior spaces.

The district’s architectural jewel, the Dining Room, dates almost a generation later to 1926. Architect Gilbert S. Underwood designed one of the late marvels of the Rustic style as defined in the northern Rockies. With its rugged stone exterior rising as it was a natural formation in the land, the dining room immediately told arriving visitors that an adventure awaited them, especially once they stepped inside and experienced the vast log interior spaces.

Other former Union Pacific buildings have been given adaptive reuse treatment by the town, with a baggage building becoming police headquarters and the former men’s dormitory has been converted into a local health clinic.

Other former Union Pacific buildings have been given adaptive reuse treatment by the town, with a baggage building becoming police headquarters and the former men’s dormitory has been converted into a local health clinic.

Thus, West Yellowstone is among Montana’s best examples of roadside architecture as distinctive 19502-1960w motels and a wide assortment of commercial types line both U.S. 191 but also the side arteries to the highway.

Thus, West Yellowstone is among Montana’s best examples of roadside architecture as distinctive 19502-1960w motels and a wide assortment of commercial types line both U.S. 191 but also the side arteries to the highway.

Three Forks, Montana, is unique in how competing railroads shaped this one small town between the 2008 and 2010. The last post discussed how the Milwaukee Road came first, and its landmark Sacajawea Inn stands at the north end of the town’s main street. On the east side–see the Google Map below–became the domain of the Northern Pacific Railroad and its spur line to the copper kingdom of Butte

Three Forks, Montana, is unique in how competing railroads shaped this one small town between the 2008 and 2010. The last post discussed how the Milwaukee Road came first, and its landmark Sacajawea Inn stands at the north end of the town’s main street. On the east side–see the Google Map below–became the domain of the Northern Pacific Railroad and its spur line to the copper kingdom of Butte

Company. In 1914 Charles Botcher bought the plant, renamed it the Ideal Cement Company and kept it in business under that name until the 1980s.

Company. In 1914 Charles Botcher bought the plant, renamed it the Ideal Cement Company and kept it in business under that name until the 1980s.

U.S. Highway 89 enters the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on its southern border, heading for its junction with U.S. Highway 2 and the reservation center of Browning. Before the junction, you cross the historic Two Medicine River, a historic corridor for the Blackfeet. To the west of the river crossing is a highway historical marker for Coldfeet School, a one-

U.S. Highway 89 enters the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on its southern border, heading for its junction with U.S. Highway 2 and the reservation center of Browning. Before the junction, you cross the historic Two Medicine River, a historic corridor for the Blackfeet. To the west of the river crossing is a highway historical marker for Coldfeet School, a one- room school (not extant) built for Blackfeet children in 1933 during the New Deal. To the east of the highway river crossing, however, was one of the earliest schools (1889) on the reservation, the Holy Family Catholic

room school (not extant) built for Blackfeet children in 1933 during the New Deal. To the east of the highway river crossing, however, was one of the earliest schools (1889) on the reservation, the Holy Family Catholic

This panorama of the mission site today shows that neither of the dormitories remain, although the historic frame barn and mill still stand (to the left) while the chapel is still a dominating element, and has been incorporated into present-day Blackfeet culture. It is in excellent shape.

This panorama of the mission site today shows that neither of the dormitories remain, although the historic frame barn and mill still stand (to the left) while the chapel is still a dominating element, and has been incorporated into present-day Blackfeet culture. It is in excellent shape. Another change is that the Blackfeet provide public interpretation of the site, through their own historical markers, which is extended into the adjacent historic cemetery, one of the most somber places in the region. The old mission is now part of the reservation’s heritage tourism effort.

Another change is that the Blackfeet provide public interpretation of the site, through their own historical markers, which is extended into the adjacent historic cemetery, one of the most somber places in the region. The old mission is now part of the reservation’s heritage tourism effort.

Returning to U.S. 89 and heading northwest, you head to the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and the town of Browning. The town is a center for reservation education, as shown by the new campus for the Blackfeet Community College.

Returning to U.S. 89 and heading northwest, you head to the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and the town of Browning. The town is a center for reservation education, as shown by the new campus for the Blackfeet Community College. Here too is another historic Catholic Church, the Little Flower Catholic Church, built in 1931, from locally available stone in a Gothic Revival style. The congregation supports a small Catholic school next door.

Here too is another historic Catholic Church, the Little Flower Catholic Church, built in 1931, from locally available stone in a Gothic Revival style. The congregation supports a small Catholic school next door. The Browning fairgrounds is an important Blackfeet recreation and cultural center, with this recent installation again providing public interpretation of Blackfeet culture.

The Browning fairgrounds is an important Blackfeet recreation and cultural center, with this recent installation again providing public interpretation of Blackfeet culture.

and U.S. 89, heading north. It created an appropriate, respectful way for the increasing number of auto tourists headed to Glacier National Park to learn about the Blackfeet in particular and Plains Indian culture in general. The famous mid-20th century anthropologist, John Ewers, had worked tribes to create the museum’s initial exhibits and collections. In the 21st century, the Blackfeet have developed additional institutions to take advantage of tourism through the nearby Glacier Peaks casino and hotel, a complex that has developed from 2011 to 2015.

and U.S. 89, heading north. It created an appropriate, respectful way for the increasing number of auto tourists headed to Glacier National Park to learn about the Blackfeet in particular and Plains Indian culture in general. The famous mid-20th century anthropologist, John Ewers, had worked tribes to create the museum’s initial exhibits and collections. In the 21st century, the Blackfeet have developed additional institutions to take advantage of tourism through the nearby Glacier Peaks casino and hotel, a complex that has developed from 2011 to 2015. These new buildings are part of a long-term continuum of tourism in Browning, starting with this old concrete tipi, built originally as a gas station in 1934 and now converted into a coffee shop. And the Blackfeet

These new buildings are part of a long-term continuum of tourism in Browning, starting with this old concrete tipi, built originally as a gas station in 1934 and now converted into a coffee shop. And the Blackfeet

Trading Post is a business found in all sorts of national park gateways–the classic place to get cheap souvenirs and t-shirts of all types, not to mention moccasins and all of the stereotypical material culture of Native American tourism in our country.

Trading Post is a business found in all sorts of national park gateways–the classic place to get cheap souvenirs and t-shirts of all types, not to mention moccasins and all of the stereotypical material culture of Native American tourism in our country.

the primary voice on what the park means, and how visitors can think about it today. The Native American presence on U.S. Highway 89 today is much more evident, with much more public interpretation, than in my travels 30 years ago.

the primary voice on what the park means, and how visitors can think about it today. The Native American presence on U.S. Highway 89 today is much more evident, with much more public interpretation, than in my travels 30 years ago. One of my favorite county seats is Choteau, where U.S. Highways 89 and 287 meet. Both of those roads were and are among my favorite to take in the state, and Choteau I quickly found had one of my favorite local dives the Wagon Wheel. Back in the day, however, I did not appreciate how the town’s history and built environment was shaped by the Sun River Irrigation project and the overall growth in the county during the first two decades of the 20th century and later a second boom in the 1940s.

One of my favorite county seats is Choteau, where U.S. Highways 89 and 287 meet. Both of those roads were and are among my favorite to take in the state, and Choteau I quickly found had one of my favorite local dives the Wagon Wheel. Back in the day, however, I did not appreciate how the town’s history and built environment was shaped by the Sun River Irrigation project and the overall growth in the county during the first two decades of the 20th century and later a second boom in the 1940s. Choteau has a different look than most towns from this era of Montana history. The centerpiece of the towns plan is not a railroad depot but the magnificent Teton County Courthouse (1906), which occupies a spot where the two federal highways junction. Designed by architects Joseph B. Gibson and George H. Shanley, the National Register-listed courthouse is made of locally quarried stone in a late interpretation of Richardsonian Romanesque style, similar to, but to a much lesser scale and detail, than H. H. Richardson’s own Allegheny County Courthouse (c. 1886) in Pittsburgh.

Choteau has a different look than most towns from this era of Montana history. The centerpiece of the towns plan is not a railroad depot but the magnificent Teton County Courthouse (1906), which occupies a spot where the two federal highways junction. Designed by architects Joseph B. Gibson and George H. Shanley, the National Register-listed courthouse is made of locally quarried stone in a late interpretation of Richardsonian Romanesque style, similar to, but to a much lesser scale and detail, than H. H. Richardson’s own Allegheny County Courthouse (c. 1886) in Pittsburgh.

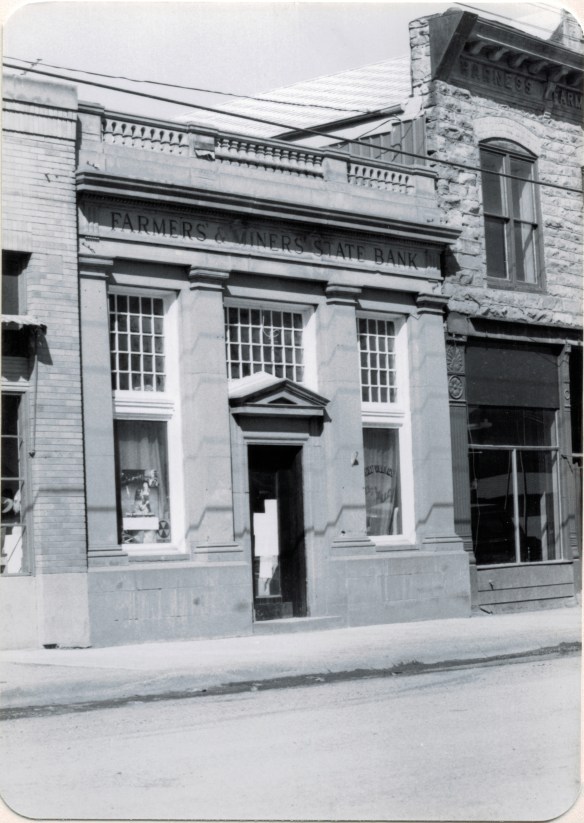

This historic neoclassical-styled bank building is now home to a coffee shop but other commercial buildings have changed very little, except for the mix of retail business. This is not a dying business district but one with a good bit of jump, of vitality.

This historic neoclassical-styled bank building is now home to a coffee shop but other commercial buildings have changed very little, except for the mix of retail business. This is not a dying business district but one with a good bit of jump, of vitality.

where the historic Bella Vista Motel–a perfect example of a 1950s motel with separate units like tiny Ranch-styled houses–has given way to a c. 2015 conversion into apartments.

where the historic Bella Vista Motel–a perfect example of a 1950s motel with separate units like tiny Ranch-styled houses–has given way to a c. 2015 conversion into apartments.

As the highway leaves the central plains east of Great Falls, it heads east through coal country (see the earlier post on Belt) and south into the Little Belt Mountains and the old mining towns of Monarch and Neihart (above). Both Cascade County towns are proud of their heritage, a story embodied in the Monarch-Neihart School, a wonderful bit of log craftsmanship from the New Deal era, a WPA project finished in 1940 that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

As the highway leaves the central plains east of Great Falls, it heads east through coal country (see the earlier post on Belt) and south into the Little Belt Mountains and the old mining towns of Monarch and Neihart (above). Both Cascade County towns are proud of their heritage, a story embodied in the Monarch-Neihart School, a wonderful bit of log craftsmanship from the New Deal era, a WPA project finished in 1940 that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When I last visited there in 2015 the combined route of U.S. 89 and 12, which passes in front of the courthouse and the center of town, was being rebuilt, giving the historic business district the look of a ghost town.

When I last visited there in 2015 the combined route of U.S. 89 and 12, which passes in front of the courthouse and the center of town, was being rebuilt, giving the historic business district the look of a ghost town.

U.S. Highway 89 continues south, crossing the historic corridor of the Milwaukee Road at Ringling, another Meagher County town discussed in an earlier post, marked by the landmark St. John’s Catholic Church.

U.S. Highway 89 continues south, crossing the historic corridor of the Milwaukee Road at Ringling, another Meagher County town discussed in an earlier post, marked by the landmark St. John’s Catholic Church. Travelers continuing south soon find themselves in Park County, entering the Shields River Valley just north of Wilsall, where highway markers and monuments, like that for “Thunder Jack” (2006) by sculptor Gary Kerby, convey the significance of the place.

Travelers continuing south soon find themselves in Park County, entering the Shields River Valley just north of Wilsall, where highway markers and monuments, like that for “Thunder Jack” (2006) by sculptor Gary Kerby, convey the significance of the place.

Wilsall was not much a place 30 years ago, a small trade town on the edge of a Northern Pacific Railroad spur line, a past still recalled by the tall elevator and old railroad corridor.

Wilsall was not much a place 30 years ago, a small trade town on the edge of a Northern Pacific Railroad spur line, a past still recalled by the tall elevator and old railroad corridor. But the growing popularity of the Shields River Valley has led to a new boom in Walsall, with old banks converted into bars and old general stores

But the growing popularity of the Shields River Valley has led to a new boom in Walsall, with old banks converted into bars and old general stores

Clyde Park Tavern is still the place to go for an adult beverage, or two. Historic grain elevators still serve local ranchers, marking the railroad line that defined the town’s landscape until the impact of the highway in the early 20th century.

Clyde Park Tavern is still the place to go for an adult beverage, or two. Historic grain elevators still serve local ranchers, marking the railroad line that defined the town’s landscape until the impact of the highway in the early 20th century.

Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation.

Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation. Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others

Along the Missouri River is Paris Gibson Park, deep in the heart of Great Falls, Montana. Gibson was one of the classic civic capitalists of the late 19th century who understood that as the community prospered he too would achieve this dream of building a great western empire, with his town of Great Falls as the center. Almost 100 years after his death, in 2015, residents, preservationists, historians, and economic developers began discussions on establishing a heritage area, centered on Great Falls, but encompassing the Missouri River as the thread between the plains and mountains, that has shaped the region, and the nation, for hundreds of years. I strongly endorse the discussion and will spend the next several posts exploring key resources in Cascade County that could serve as the foundation for a larger regional story.

Along the Missouri River is Paris Gibson Park, deep in the heart of Great Falls, Montana. Gibson was one of the classic civic capitalists of the late 19th century who understood that as the community prospered he too would achieve this dream of building a great western empire, with his town of Great Falls as the center. Almost 100 years after his death, in 2015, residents, preservationists, historians, and economic developers began discussions on establishing a heritage area, centered on Great Falls, but encompassing the Missouri River as the thread between the plains and mountains, that has shaped the region, and the nation, for hundreds of years. I strongly endorse the discussion and will spend the next several posts exploring key resources in Cascade County that could serve as the foundation for a larger regional story.

Thirty years later, Belt’s population had bottomed out, declining to under 600 by the time of the 2010 census. But both times I have stopped by, in 2013 and 2015, the town has a sense of life about it, and hope. The town’s two historic taverns, the Harvest Moon Tavern and the Belt Creek Brew Pub, as well as the Black Diamond Bar and Supper Club attract visitors from nearby Great Falls and elsewhere, giving the place a sense of life at evenings and weekends.

Thirty years later, Belt’s population had bottomed out, declining to under 600 by the time of the 2010 census. But both times I have stopped by, in 2013 and 2015, the town has a sense of life about it, and hope. The town’s two historic taverns, the Harvest Moon Tavern and the Belt Creek Brew Pub, as well as the Black Diamond Bar and Supper Club attract visitors from nearby Great Falls and elsewhere, giving the place a sense of life at evenings and weekends.

When planners talk about heritage areas, they often focus on the contributions of local entrepreneurs who take historic buildings, like the Pioneer above, and breathe new life into them. Throughout small town Montana and urban commercial districts, new breweries and distilleries are creating such opportunities.

When planners talk about heritage areas, they often focus on the contributions of local entrepreneurs who take historic buildings, like the Pioneer above, and breathe new life into them. Throughout small town Montana and urban commercial districts, new breweries and distilleries are creating such opportunities.

Belt has a range of historic buildings, mostly of vernacular two-part commercial style that speak strongly to the boom of 1900 to 1920. The Victorian-styled cornice of the Belt Hardware Store (1896) speaks to the town’s origins. The Knights of Pythias Lodge of 1916 has been restored as a community theater, another reason for visitors to stop and explore.

Belt has a range of historic buildings, mostly of vernacular two-part commercial style that speak strongly to the boom of 1900 to 1920. The Victorian-styled cornice of the Belt Hardware Store (1896) speaks to the town’s origins. The Knights of Pythias Lodge of 1916 has been restored as a community theater, another reason for visitors to stop and explore. The result is a living cultural experience, since nothing in Belt is over-restored or phony feeling. It is still a gritty, no frills place. That feel is complemented by the Belt museum, which is housed in a historic jail on road down into town and within sight on a railroad trestle, a reminder of what literally drove the town’s development, coal for the railroads.

The result is a living cultural experience, since nothing in Belt is over-restored or phony feeling. It is still a gritty, no frills place. That feel is complemented by the Belt museum, which is housed in a historic jail on road down into town and within sight on a railroad trestle, a reminder of what literally drove the town’s development, coal for the railroads. During the 1984 survey, I gave the jail a good bit of attention since this stone building spoke to the craftsmanship of the era, the centrality of local government as the town developed, and the reality that this building was the only thing in Belt listed in the National Register of Historic Places. But in 2004 the state historic preservation office approved the Belt commercial historic district, and that designation has done much to drive the town’s recent revival. Belt is just the first place that speaks to the promise of the Great Falls heritage area concept.

During the 1984 survey, I gave the jail a good bit of attention since this stone building spoke to the craftsmanship of the era, the centrality of local government as the town developed, and the reality that this building was the only thing in Belt listed in the National Register of Historic Places. But in 2004 the state historic preservation office approved the Belt commercial historic district, and that designation has done much to drive the town’s recent revival. Belt is just the first place that speaks to the promise of the Great Falls heritage area concept.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town. How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history.

How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history. Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society.

Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society. What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense.

What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense. Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation.

Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation. Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods. The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and

The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today.

residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today. As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis.

As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis. Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.