Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as

Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as

this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

population barely tops 50. That is enough, once kids from surrounding ranches are added, to support the Jackson elementary school–a key to the town’s survival over the years.

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984.

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984.

But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats!

But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats!

Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Grant only attracts the more hardy traveler, mostly hunters. The Horse Prairie Stage Stop is combination restaurant, bar, and hotel–a throwback to isolated outposts of the late 19th century where exhausted travelers would bunk for a night.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers.

Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

Certainly that is the case at Dewey, where the Dewey Bar attracts all sorts of patrons, even the four-legged kind. The early 20th century false-front general store that still operated in 1984 is now closed, but the town has protected two log barns that still front Montana Highway 43.

Wise River still has four primary components that can characterize a isolated western town: a post office, a school, a bar/cafe, and a community center. It is also the location for one of the ranger stations of the Beaverhead National Forest.

The station has a new modernist style administrative building but it also retains its early twentieth century work buildings and ranger residence, a Bungalow design out of logs.

The forest service station has provided Wise River with a degree of stability over the decades, aided by the town’s tiny post office and its early 20th century public school.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

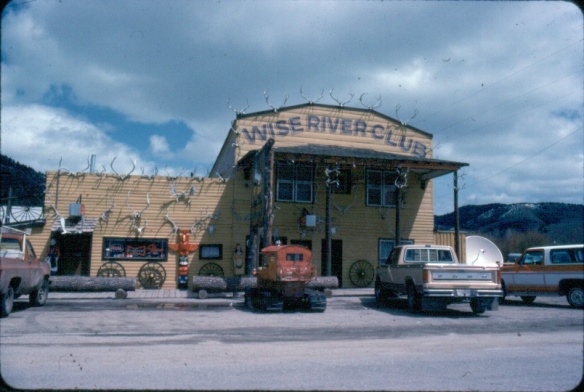

But to my eye the most important institution, especially for a traveler like me, is one of the state’s most interesting bits of roadside architecture, the Wise River Club. I have already written about this building, from my 1984 travels.

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building.

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building.

But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar.

But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar.

Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions.

Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions.

The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

Nestled where Montana Highway 287 encounters U.S. Highway 287 in the southern end of Madison County, Ennis has changed in significant ways in the last 30 years. Its earlier dependence on automobile tourism to Yellowstone National Park has shifted into the favor of population growth and development in this portion of the county.

Nestled where Montana Highway 287 encounters U.S. Highway 287 in the southern end of Madison County, Ennis has changed in significant ways in the last 30 years. Its earlier dependence on automobile tourism to Yellowstone National Park has shifted into the favor of population growth and development in this portion of the county. The iconic Ennis Cafe, always a favorite place back in the day of the statewide work, remains, with a new false front emphasizing the wildlife and open spaces of this area. That place, along with several classic watering holes, served not only locals but the

The iconic Ennis Cafe, always a favorite place back in the day of the statewide work, remains, with a new false front emphasizing the wildlife and open spaces of this area. That place, along with several classic watering holes, served not only locals but the

of a section of the highway where you will encounter magnificent views of the Madison River Valley and open ranch lands.

of a section of the highway where you will encounter magnificent views of the Madison River Valley and open ranch lands.

In thinking about returning to Montana in 2012 and carrying out a huge “re-survey” of the places I had explored for the state historic preservation plan process 30 years earlier, Butte was high on my list of priorities. Not that the city and its surroundings had been given little attention in the early 1980s–the Copper City was already recognized as a National Historic Landmark, and a team of historians, architects, and engineers had just finished a large study of its built environment for the Historic American Building Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record. No, I wanted to go back because by 1985 many people counted Butte down and out, yet it had survived and started to reinvent itself. Not

In thinking about returning to Montana in 2012 and carrying out a huge “re-survey” of the places I had explored for the state historic preservation plan process 30 years earlier, Butte was high on my list of priorities. Not that the city and its surroundings had been given little attention in the early 1980s–the Copper City was already recognized as a National Historic Landmark, and a team of historians, architects, and engineers had just finished a large study of its built environment for the Historic American Building Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record. No, I wanted to go back because by 1985 many people counted Butte down and out, yet it had survived and started to reinvent itself. Not as a ghost town or the skeleton of a great mining city but as a revitalized place, both economically and culturally, centered in a strong core community, even though the challenges in front of it remain daunting, even overwhelming at times.

as a ghost town or the skeleton of a great mining city but as a revitalized place, both economically and culturally, centered in a strong core community, even though the challenges in front of it remain daunting, even overwhelming at times. The environmental degradation left when the hard rock mines shut down is one burden that Butte has shouldered, with the help of the federal superfund program. Still, no matter how scientifically this landscape has been “cleaned up,” it remained scarred, and it is a far different challenge to build back hope into a place stripped of its life. Yet high over the city is a sign of the change to come in the Mountain Con Mine site.

The environmental degradation left when the hard rock mines shut down is one burden that Butte has shouldered, with the help of the federal superfund program. Still, no matter how scientifically this landscape has been “cleaned up,” it remained scarred, and it is a far different challenge to build back hope into a place stripped of its life. Yet high over the city is a sign of the change to come in the Mountain Con Mine site. Still labeled as a Mile High and a Mile Deep place, the mine property is stunning, not only for its technological assertion–imagine working that high, and going that deep–but for its conversion into the walking/hiking/biking trails that encircle the city and present it with such potential as a recreational landscape.

Still labeled as a Mile High and a Mile Deep place, the mine property is stunning, not only for its technological assertion–imagine working that high, and going that deep–but for its conversion into the walking/hiking/biking trails that encircle the city and present it with such potential as a recreational landscape.

ago, with all sorts of signs of new investment, new pride, and community identity. It may have lost a step, or two, and its swagger may not be quite as exaggerated as it was in the mid-20th century, but it remains a place with its own feel, its own funk. For me, the reopening of the M&M Bar on Main Street–a legendary dive once shuttered, reopened, and shuttered again–gives me hope for Butte in the 21st century. Around the corner is

ago, with all sorts of signs of new investment, new pride, and community identity. It may have lost a step, or two, and its swagger may not be quite as exaggerated as it was in the mid-20th century, but it remains a place with its own feel, its own funk. For me, the reopening of the M&M Bar on Main Street–a legendary dive once shuttered, reopened, and shuttered again–gives me hope for Butte in the 21st century. Around the corner is

Mercury Street; at the same time the sex trade was alive and well to the east of that same street in a series of boarding houses and hotels. The Dumas Brothel, discussed in an earlier post, is listed in the National Register and its future as an adaptive reuse project and place for public interpretation is promising but not yet realized. African Americans in

Mercury Street; at the same time the sex trade was alive and well to the east of that same street in a series of boarding houses and hotels. The Dumas Brothel, discussed in an earlier post, is listed in the National Register and its future as an adaptive reuse project and place for public interpretation is promising but not yet realized. African Americans in

The massive building still dominates the Uptown building, making its closure in Butte in 1980 that more disturbing for residents. When I did my preservation plan work in 1984-1985 the issue of what to do with the Hennessy was at the forefront. By the end of the decade, ENTECH renovated the building and reopened it fully for business. In 2010 came the popular Hennessy Market–giving the growing number of Uptown residents a grocery store once again.

The massive building still dominates the Uptown building, making its closure in Butte in 1980 that more disturbing for residents. When I did my preservation plan work in 1984-1985 the issue of what to do with the Hennessy was at the forefront. By the end of the decade, ENTECH renovated the building and reopened it fully for business. In 2010 came the popular Hennessy Market–giving the growing number of Uptown residents a grocery store once again. The Sliver Bow Club building (1906-7) also has shifted its purpose, from being the stately and eloquent clubhouse of the city’s elite to becoming a place for public offices and meetings in its once exclusive spaces. Originally conceived by the same Spokane architects who designed the Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park, according to recent research by museum curator and preservationist Patty Dean, the building’s architects ended up being Link and Haire, the noted Montana architectural firm.

The Sliver Bow Club building (1906-7) also has shifted its purpose, from being the stately and eloquent clubhouse of the city’s elite to becoming a place for public offices and meetings in its once exclusive spaces. Originally conceived by the same Spokane architects who designed the Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park, according to recent research by museum curator and preservationist Patty Dean, the building’s architects ended up being Link and Haire, the noted Montana architectural firm.

Located between the Gallatin River and Interstate I-90, Logan is a forgotten yet still historically significant railroad junction on the Northern Pacific Railroad. Established c.

Located between the Gallatin River and Interstate I-90, Logan is a forgotten yet still historically significant railroad junction on the Northern Pacific Railroad. Established c.

From 1983-85 Belgrade became one of my favorite Northern Pacific railroad towns. Often I would leave the interstate here, stop at truly one of the great small town bars/cafes along the town’s railroad corridors, and then travel on old U.S. 10 (the town’s Main Street) on to Manhattan, Logan, and Three Forks before popping up on US 287 and continuing to home in Helena.

From 1983-85 Belgrade became one of my favorite Northern Pacific railroad towns. Often I would leave the interstate here, stop at truly one of the great small town bars/cafes along the town’s railroad corridors, and then travel on old U.S. 10 (the town’s Main Street) on to Manhattan, Logan, and Three Forks before popping up on US 287 and continuing to home in Helena.

Despite the boom, several landmarks remain. The Belgrade Community Church, built in 1904 as the town’s Presbyterian church, served in the 1980s as a joint church building for both the town’s Presbyterians and Baptists. This impressive Gothic Revival building had received several updates and additions in the mid-1970s. It became the Community Church in 1992 as the Presbyterians left and the American Baptist Church took over sole control of this historic church building.

Despite the boom, several landmarks remain. The Belgrade Community Church, built in 1904 as the town’s Presbyterian church, served in the 1980s as a joint church building for both the town’s Presbyterians and Baptists. This impressive Gothic Revival building had received several updates and additions in the mid-1970s. It became the Community Church in 1992 as the Presbyterians left and the American Baptist Church took over sole control of this historic church building.