Multiple news stories and headlines at the end of 2016 spoke of the federal government’s warm relationship with those residing in the Kremlin, Moscow, Russia. Have no idea of what the federal government’s new relationship with the Kremlin in Moscow might mean, but it did get me thinking that, perhaps, on the off chance, it might bring new federal attention to the Montana Kremlin–a tiny Great Northern Railroad town in Hill County.

The federal government first impacted this place in 1911 after it threw open the old Fort Assiniboine reserve to homesteading. The railroad had maintained a stop here as early as 1901 but with the federal opening of new land, permanent settlers came to carve out their new homesteads.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

During the Great Depression, the federal government made its second impact on the town. New Deal agencies installed a new water system. Funding from the Public Works Administration led to the construction of a new school in 1937-38, an institution, with changes, that still serves the community.

I have wondered if this separate building on the school yard was built as the lunchroom–it is similar to lunchroom buildings I have found in the South, or was it built as a teacher’s residence. You find that in the northern plains.

The early history of Kremlin is marked by one architecturally interesting building–this rectangular building covered with pressed tin–when new it must have gleamed in the

sun. Note the classical cornice at the top of the roof line–this entire decorative scheme belongs more to the late 19th century but here it is, in Kremlin, from the 2nd or 3rd decade of the 20th century.

Kremlin’s Lutheran Church (below) in 2013 was holding services every other week in the month, while the Methodist (?) Church had already seemingly closed its doors. Religious freedom thrives in Montana’s Kremlin, probably not so much in that other Kremlin.

Nor would that other Kremlin in the past have cared a whit about the Montana Farmers Union, which has shaped the life and economy of Kremlin and its neighbors for the decades. That other Kremlin, however, would like the oil………

The last time Kremlin directly felt the hand of the federal government was in this decade, when the U.S. Postal Service, which had been building new small-town facilities like the one in Kremlin below for a decade, announced that it needed to close hundreds of rural post offices.

Kremlin residents joined their neighbors in protest: and the federal backed down. When I last visited Kremlin 3 years ago, I mailed a letter from its post office. Persistence, commitment, community mark the Montana Kremlin–maybe that’s why I would rather hear about this place in Hill County than that other one, which suddenly new decision makers are courting.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley. The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

Bozeman has boomed with many new chef-driven restaurants but of the downtown establishments my favorite for good fresh, creative food remains the Co-Op Downtown nestled within the Gallatin Block, a historic building, tastefully renovated, in the downtown historic district.

Bozeman has boomed with many new chef-driven restaurants but of the downtown establishments my favorite for good fresh, creative food remains the Co-Op Downtown nestled within the Gallatin Block, a historic building, tastefully renovated, in the downtown historic district.

head to Miles City, which is the place to go if you wonder, still, “where’s the beef” and a city that is the proud home of the famous Montana Bar.

head to Miles City, which is the place to go if you wonder, still, “where’s the beef” and a city that is the proud home of the famous Montana Bar.

within New Deal landscape that forever changed the look of this region in the 1930s. Locals and tourists mix together–because the hotel is the only place to go, unless you want to backtrack to Glasgow and check out Sam’s Supper Club on U.S. Highway 2, and its equally neat 1960s roadside look.

within New Deal landscape that forever changed the look of this region in the 1930s. Locals and tourists mix together–because the hotel is the only place to go, unless you want to backtrack to Glasgow and check out Sam’s Supper Club on U.S. Highway 2, and its equally neat 1960s roadside look.

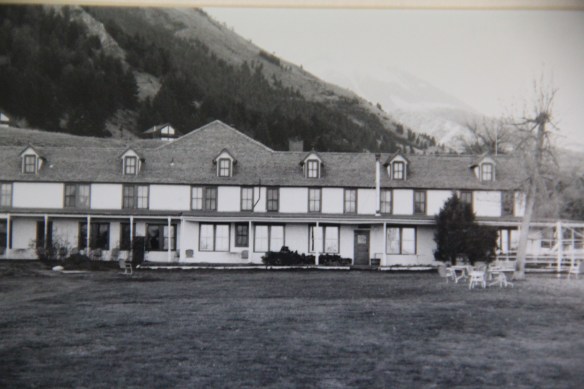

The most popular Montana gateway into Yellowstone National Park is at Gardiner, in the southern tip of Park County. Here is where the Northern Pacific Railway stopped its trains, at a Rustic styled passenger station long ago demolished, and travelers passed through the gate above–designed by architect Robert Reamer–and started their journey into the park.

The most popular Montana gateway into Yellowstone National Park is at Gardiner, in the southern tip of Park County. Here is where the Northern Pacific Railway stopped its trains, at a Rustic styled passenger station long ago demolished, and travelers passed through the gate above–designed by architect Robert Reamer–and started their journey into the park. By the mid-20th century, Gardiner had become a highway town, the place in-between the beautiful drive through the Paradise Valley on U.S. Highway 89 (now a local paved road)

By the mid-20th century, Gardiner had become a highway town, the place in-between the beautiful drive through the Paradise Valley on U.S. Highway 89 (now a local paved road)

The plan to develop a new Gardiner library at the old Northern Pacific depot site at part of the Gardiner Gateway Project is particularly promising, giving the town a new community anchor but also reconnecting it to the railroad landscape it was once part of. Something indeed to look for when I next visit this Yellowstone Gateway.

The plan to develop a new Gardiner library at the old Northern Pacific depot site at part of the Gardiner Gateway Project is particularly promising, giving the town a new community anchor but also reconnecting it to the railroad landscape it was once part of. Something indeed to look for when I next visit this Yellowstone Gateway. Montana’s gateways into Yellowstone National Park are known far and wide. The most popular are associated with the trains that delivered mostly easterners to the wonderland of the park–West Yellowstone for the Union Pacific line and Gardiner for the Northern Pacific Railway.

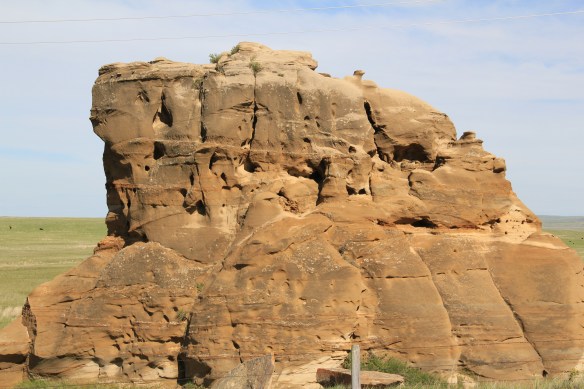

Montana’s gateways into Yellowstone National Park are known far and wide. The most popular are associated with the trains that delivered mostly easterners to the wonderland of the park–West Yellowstone for the Union Pacific line and Gardiner for the Northern Pacific Railway. Cooke City, located in the corner of Park County, was never a railroad town but an overland connection that did not become popular until the development of the Beartooth Highway out of Red Lodge in the 1920s.

Cooke City, located in the corner of Park County, was never a railroad town but an overland connection that did not become popular until the development of the Beartooth Highway out of Red Lodge in the 1920s. It is all about the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) here–when it opens, Cooke City booms as a tourism oasis. When the highway closes for its long winter, business doesn’t end since the road to Mammoth Hot Springs far to the west is kept open as best as it can be, but the number of visitors drops remarkably. Snow mobile traffic in the winter has meant a lot to local business in the last 30 years.

It is all about the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) here–when it opens, Cooke City booms as a tourism oasis. When the highway closes for its long winter, business doesn’t end since the road to Mammoth Hot Springs far to the west is kept open as best as it can be, but the number of visitors drops remarkably. Snow mobile traffic in the winter has meant a lot to local business in the last 30 years.

Cooke City uses its mining past to define its identity today, from moving log mining shacks and cabins into town, as shown above, for potential new lures for tourism, to the recently established visitor center and museum, which includes some of the local mining

Cooke City uses its mining past to define its identity today, from moving log mining shacks and cabins into town, as shown above, for potential new lures for tourism, to the recently established visitor center and museum, which includes some of the local mining

Perhaps the best example is the rustic yet modern styling of the Mt Republic Chapel of Peace between Silver Gate and Cooke City on U.S. 212. It is no match for the soaring mountains that surround it but its quiet dignity reflects well the people and environment of this part of Montana.

Perhaps the best example is the rustic yet modern styling of the Mt Republic Chapel of Peace between Silver Gate and Cooke City on U.S. 212. It is no match for the soaring mountains that surround it but its quiet dignity reflects well the people and environment of this part of Montana.

The same can be said for Hoosier’s Bar–a favorite haunt here in Cooke City for several decades, easy to find with its neon sign, and then there is the throwback telephone booth–a good idea since many cell phones search for coverage in this area. Cooke City and Silver Gate are the smallest Montana gateways into Yellowstone National Park but they tell and preserve their story well.

The same can be said for Hoosier’s Bar–a favorite haunt here in Cooke City for several decades, easy to find with its neon sign, and then there is the throwback telephone booth–a good idea since many cell phones search for coverage in this area. Cooke City and Silver Gate are the smallest Montana gateways into Yellowstone National Park but they tell and preserve their story well. My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89.

My friends in the environs of Helena have been surprised that after 300 something posts I had yet to say anything about Augusta, a crossroads town in northern Lewis and Clark County along U.S. Highway 287, during my revisit of the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan. They knew that I loved the open range drive to Augusta, whether approaching from U.S. 287 or U.S. Highway 89. Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Then, the various businesses and bars along Main Street represented not just a favorite place in rural Lewis and Clark County, but also document a classic western town with great roadside architecture such as the Wagon Wheel Motel.

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta

Augusta began as a crossroads town for neighboring ranches; the later extension of a railroad spur to nearby Gilman spurred competition between the two towns. But Augusta  won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

won that battle–today not much outside of the Montana Highway Historical marker, a steel bridge, and a disappearing railroad corridor remains of Gilman.

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined?

But I like the football field almost as much as the historic school–could a more neighborhood setting even be imagined? Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Then there are historic commercial buildings from the early 20th century–several with National Register qualities, especially the F. M. Mack General Merchandise store–a frame building with paired bracketed cornice.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

Over 300 people call Augusta home today, a slight increase since my work 30 years ago. The community not only has kept the historic buildings noted above, residents also have opened the Augusta Area Museum–heritage is clearly part of the town’s future.

entertained generations of Grizzly students and fans–note the window mural. But it is just one of several favorite Stockman’s Bars I have encountered in my Montana fieldwork. My top choice is actually on the other end of the state–almost in North Dakota in fact–the Stockman’s Bar in Wibaux.

entertained generations of Grizzly students and fans–note the window mural. But it is just one of several favorite Stockman’s Bars I have encountered in my Montana fieldwork. My top choice is actually on the other end of the state–almost in North Dakota in fact–the Stockman’s Bar in Wibaux.

The woman’s club began c. 1921 and had already made a major contribution to the town’s well-being in establishing its first library. After World War II, however, club members felt they should once again help build the community, by building a youth center and veterans memorial garden. Mrs. Norman Good proposed the project in 1946 and Mrs. G. D. Martin provided the first substantial donation. The club then held fundraisers of all sorts. By 1950, construction was underway, with contractor Clyde Wilson building the center with logs from Colby and Sons in Kila, Montana.

The woman’s club began c. 1921 and had already made a major contribution to the town’s well-being in establishing its first library. After World War II, however, club members felt they should once again help build the community, by building a youth center and veterans memorial garden. Mrs. Norman Good proposed the project in 1946 and Mrs. G. D. Martin provided the first substantial donation. The club then held fundraisers of all sorts. By 1950, construction was underway, with contractor Clyde Wilson building the center with logs from Colby and Sons in Kila, Montana. As the youth center was under construction, the woman’s club also reached an agreement with the school board to use land for the construction of a new football field, named McQuitty Field. Located behind the youth center, the field opened in 1950.

As the youth center was under construction, the woman’s club also reached an agreement with the school board to use land for the construction of a new football field, named McQuitty Field. Located behind the youth center, the field opened in 1950.

Thus, on U.S. Highway 12 lies the public recreation heart of Harlowton–a postwar gift of residents and service clubs to the community. In 1956, the woman’s club deeded the Youth Center to the Kiwanis Club, which still manages it today.

Thus, on U.S. Highway 12 lies the public recreation heart of Harlowton–a postwar gift of residents and service clubs to the community. In 1956, the woman’s club deeded the Youth Center to the Kiwanis Club, which still manages it today.

Road, it once also had several hotels and more short-term housing for workers and travelers–a good bit of that has disappeared, or is disappearing.

Road, it once also had several hotels and more short-term housing for workers and travelers–a good bit of that has disappeared, or is disappearing.

It is difficult to visit Harlowton and not notice the mammoth Montana Flour Mills set of concrete grain silos–today’s silent sentinels of what ranchers once produced in abundance in these lands.

It is difficult to visit Harlowton and not notice the mammoth Montana Flour Mills set of concrete grain silos–today’s silent sentinels of what ranchers once produced in abundance in these lands. The mill, made from locally quarried stone, came within months of the completion of the railroad to Harlowton–the concrete silos reflected the hopes of investors and local ranchers, as grain production soared in the 1910s–reaching some 1.2 million bushels in 1918. It wasn’t called Wheatland County for nothing. I still wish the big electric sign that once adorned the silos was still there.

The mill, made from locally quarried stone, came within months of the completion of the railroad to Harlowton–the concrete silos reflected the hopes of investors and local ranchers, as grain production soared in the 1910s–reaching some 1.2 million bushels in 1918. It wasn’t called Wheatland County for nothing. I still wish the big electric sign that once adorned the silos was still there.

Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.