Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

A photo of the asylum from 2007

years later. The architect was John C. Paulsen, who then served as the State Architect. The building represents an early effort by the state to provide for its citizens, and the presence of the institution in Boulder shaped that town’s history for the next 120 years.

Boulder is a place of impressive public buildings. The Jefferson County Courthouse (1888-89) is another piece of Victorian architecture, in the Dichardsonian Romanesque style, again by John K. Paulsen. It was listed in the National Register in 1980.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Indeed the importance of schools to not only the state’s history of education but the mere survival of communities has been pinpointed by various state preservation groups and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Jefferson County still has many significant surviving school buildings from the early 20th century, none of which have been listed yet in the National Register.

Carter School, 1916, Montana City

Clancy School, now the Jefferson County Museum

Basin school, still in use

Caldwell school, one of the few buildings left in this old railroad town

Whitehall still has its impressive Gothic style gymnasium from the 1920s while the school itself shows how this part of the county has gained in population since 1985.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

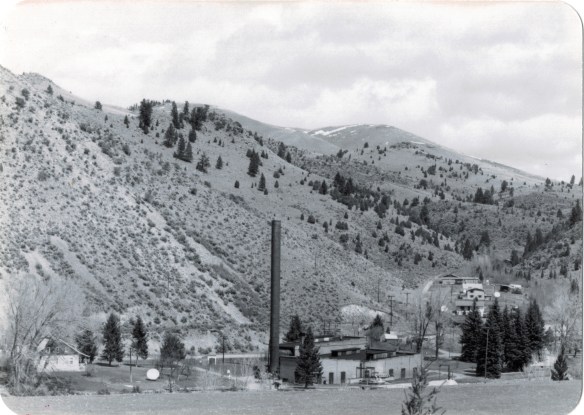

Irrigation and sugar beet cultivation are key 20th century agricultural themes, typically associated with eastern and central Montana. Jefferson County tells that story too, in a different way, at Whitehall. The irrigation ditches are everywhere and the tall concrete stack of the sugar refinery plant still looms over the town.

In 1917 Amalgamated Sugar Company, based in Utah, formed the Jefferson Valley Sugar Company and began to construct but did not finish a refinery at Whitehall. The venture did not begin well, and the works were later sold to the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company in 1920, which never finished the plant but left the stack standing. Nearby is Sugar Beet

Row, where hipped roof duplex residences typical of c. 1920 company towns are still lined up, and in use, although their exteriors have changed over the decades.

Through many posts in this blog, I have identified those informal yet very important community centers found in urban neighborhoods and rural outposts across the state–bars and taverns. Jefferson County has plenty of famous classic watering holes, such as Ting’s Bar in Jefferson City, the Windsor Bar in Boulder, or the Two Bit Bar in Whitehall, not forgetting Roper Lanes and Lounge in Whitehall.

Speaking of recreation, Jefferson County also has one of my favorite hot springs in all of the west, the Boulder Hot Springs along Montana Highway 69. Here is a classic oasis of the early 20th century, complete in Spanish Revival style, and listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Its rough worn exterior only hints at the marvel of its pool and experience of this place.

Mining always has been part of Jefferson County’s livelihood with still active mines near Whitehall and at Wickes. The county also has significant early remnants of the state’s

The coke ovens above are from Wickes (L) and Alhambra (R) while the image directly above is of 21st century mining continuing at Wickes.

mining era, with still extant (but still threatened as well) charcoal kilns at Wickes (1881) and at Alhambra. Naturally with the mining came railroads early to Jefferson County. As you travel Interstate I-15 between Butte and Helena, you are generally following the route of the Montana Central, which connected the mines in Butte to the smelter in Great Falls, and a part of the abandoned roadbed can still be followed.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Corbin concentrator site, 1984

The Northern Pacific Railroad and the Milwaukee Road were both active in the southern end of the county. Along one stretch of the Jefferson River, which is followed by Montana Highway 2 (old U.S. Highway 10), you are actually traversing an ancient transportation route, created by the river, the railroads, and the federal highway. The Northern Pacific tracks are immediately next to the highway between the road and the Jefferson River; the Milwaukee corridor is on the opposite side of the river.

The most famous remnant of Montana’s mining era is the ghost town at Elkhorn. Of course the phrase ghost town is a brand name, not reality. People still live in Elkhorn–indeed more now than when I last visited 25 years ago. Another change is that the two primary landmarks of the town, Fraternity Hall and Gilliam Hall, have become a pocket state park, and are in better preservation shape than in the past.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

The adjacent Gillian Hall is also an important building, not as architecturally ornate as Fraternity Hall, but typical of mining town entertainment houses with bars and food on the first floor, and a dance hall on the second floor.

While the state park properties dominate what remains at Elkhorn, it is the general unplanned, ramshackle appearance and arrangement of the town that conveys a bit of what these bustling places were like over 130 years ago–residences and businesses alike thrown up quickly because everyone wanted to make their pile and then move on.

Elkhorn is not the only place of compelling vernacular architecture. Visible along Interstate I-15 is a remarkable set of log ranch buildings near Elk Park, once a major dairy center serving Butte during the 1st half of the twentieth century. John and Rudy Parini constructed the gambrel-roof log barn, to expand production available from an earlier log barn by their father, in c. 1929. The Parini ranch ever since has been a landmark for travelers between Butte and Helena.

Nearby is another frame dairy barn from the 1920s, constructed and operated by brothers George and William Francine. The barns are powerful artifacts of the interplay between urban development and agricultural innovation in Jefferson County in the 20th century.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte. The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

West of Whitehall is another 20th century roadside attraction, Lewis and Clark Caverns, a property with one of the most interesting conservation histories in the nation. It began as a privately developed site and then between 1908 and 1911 it became the Lewis and Clark Cavern National Monument during the administration of President William Howard Taft. Federal authorities believed that the caverns had a direct connection to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Corps of Discovery camped nearby on July 31, 1805, but had no direct association with the caverns. A portion of their route is within the park’s boundaries.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

Faith, and the persistence of early churches across rural Montana, is perhaps the most appropriate last theme to explore in Jefferson County. St. John the Evangelist (1880-1881) dominates the landscape of the Boulder Valley, along Montana Highway 69, like few other buildings. This straightforward statement of faith in a frame Gothic styled building, complete with a historic cemetery at the back, is a reminder of the early Catholic settlers of the valley, and how diversity is yet another reality of the Montana experience.

Montana Highway 1, designated the Pintler Scenic Route, has long been one of my favorite roads. It was the first Montana road to be paved in its entirety. During the state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, I documented the route as U.S. 10A, but once government officials decided to decommission the U.S. 10 designation in 1986, the name U.S. 10A also went away. t. In its early decades the route had passed through Opportunity to Anonconda onto Phillipsburg and then Drummond, but for all of my time in Montana, the highway has gone from Interstate I-90, Anaconda/Opportunity exit to the west and then north to the Drummond exit on the same interstate. There is a new 21st century rest stop center at the Anaconda I-90 exit that has a Montana Department of Transportation marker about the mountain ranges and the Pintler route.

Montana Highway 1, designated the Pintler Scenic Route, has long been one of my favorite roads. It was the first Montana road to be paved in its entirety. During the state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, I documented the route as U.S. 10A, but once government officials decided to decommission the U.S. 10 designation in 1986, the name U.S. 10A also went away. t. In its early decades the route had passed through Opportunity to Anonconda onto Phillipsburg and then Drummond, but for all of my time in Montana, the highway has gone from Interstate I-90, Anaconda/Opportunity exit to the west and then north to the Drummond exit on the same interstate. There is a new 21st century rest stop center at the Anaconda I-90 exit that has a Montana Department of Transportation marker about the mountain ranges and the Pintler route.

The town of Opportunity was not a priority for my travels in 1984-1985 but recent scholarship on how local residents have fought back against the decades of pollution from Anaconda’s Washoe Stack led me to give this small town of 500 a new look. The book is Brad Tyer’s Opportunity, Montana: Big Copper, Bad Water, and the Burial of an American Landscape (2014). Tyler details how the success of Anaconda also meant the sacrifice of thousands of surrounding acres to the pollution belching daily from the Washoe Stack until it closed in 1981. He then reviews in detail how in the 21st century, EPA heaped a new disaster on the town by moving Milltown wastes from the Clark’s Fork River near Missoula to Opportunity, telling locals that the Milltown soil would be new top soil for Opportunity. The environmental solution didn’t work, leaving the town in worse shape than before.

The town of Opportunity was not a priority for my travels in 1984-1985 but recent scholarship on how local residents have fought back against the decades of pollution from Anaconda’s Washoe Stack led me to give this small town of 500 a new look. The book is Brad Tyer’s Opportunity, Montana: Big Copper, Bad Water, and the Burial of an American Landscape (2014). Tyler details how the success of Anaconda also meant the sacrifice of thousands of surrounding acres to the pollution belching daily from the Washoe Stack until it closed in 1981. He then reviews in detail how in the 21st century, EPA heaped a new disaster on the town by moving Milltown wastes from the Clark’s Fork River near Missoula to Opportunity, telling locals that the Milltown soil would be new top soil for Opportunity. The environmental solution didn’t work, leaving the town in worse shape than before. Opportunity residents got a small fraction of SuperFund monies for the environmental cleanup in the form of Beaver Creek park. But the centerpiece of the park, the Opportunity School built for residents in 1914 by the Anaconda Company, has been mothballed for now. It operated from 1914 until the smelter ceased operations in 1981 and

Opportunity residents got a small fraction of SuperFund monies for the environmental cleanup in the form of Beaver Creek park. But the centerpiece of the park, the Opportunity School built for residents in 1914 by the Anaconda Company, has been mothballed for now. It operated from 1914 until the smelter ceased operations in 1981 and served as the community’s focal point. Restoration of the school is problematic due to the prior use of asbestos, meaning the federally funded park is only partially finished since the SuperFund support is now gone.

served as the community’s focal point. Restoration of the school is problematic due to the prior use of asbestos, meaning the federally funded park is only partially finished since the SuperFund support is now gone.

Sitting at 6,425 feet in elevation Georgetown Lake covers over 3700 acres. Today it is very much a recreational landscape but when it was created in 1885 its job was to generate electrical power for the nearby mines since it stood roughly equal distance between

Sitting at 6,425 feet in elevation Georgetown Lake covers over 3700 acres. Today it is very much a recreational landscape but when it was created in 1885 its job was to generate electrical power for the nearby mines since it stood roughly equal distance between As the state highway historical marker above documents, this high country area was another mining region. With an vantage point above the lake, Southern Cross is a significant remnant of the mining activities from the early 20th century. The mines here

As the state highway historical marker above documents, this high country area was another mining region. With an vantage point above the lake, Southern Cross is a significant remnant of the mining activities from the early 20th century. The mines here began operation in the mid-1860s and production continued for until World War II. The settlement was largely Finnish and Swedish in the early 20th century when most of the remaining buildings were constructed.

began operation in the mid-1860s and production continued for until World War II. The settlement was largely Finnish and Swedish in the early 20th century when most of the remaining buildings were constructed.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole. There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.

There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley.

Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley. At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93. And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

And the coffee is always hot, and strong. Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as

Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984.

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984. But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats!

But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats! Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers. Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

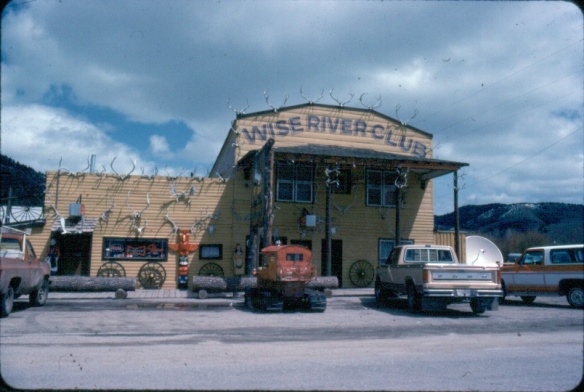

Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building.

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building. But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar.

But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar. Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions.

Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions. The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains. Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years.

Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years. The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution

The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies. I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer

I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school. While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students.

While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students. Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.

When travelers, and most Montana residents even, speak of Silver Bow County, they think of Butte. Outside of the Copper City, however, are small towns and a very different way of life. To the west we have already discussed Ramsay and its beginnings as a munitions factory town during World War I. Let’s shift attention now to the southern tip of the county and two places along the historic Union Pacific spur line, the Utah Northern Railroad, into Butte.

When travelers, and most Montana residents even, speak of Silver Bow County, they think of Butte. Outside of the Copper City, however, are small towns and a very different way of life. To the west we have already discussed Ramsay and its beginnings as a munitions factory town during World War I. Let’s shift attention now to the southern tip of the county and two places along the historic Union Pacific spur line, the Utah Northern Railroad, into Butte.

when Melrose was a substantial, busy place. This 1870s-1880s history is largely forgotten today as the town has evolved into a sportsmen’s stop off Interstate I-15 due to its great access to the Big Hole River and surrounding national forests as well as the quite marvy Melrose Bar and Cafe, a classic western watering hole.

when Melrose was a substantial, busy place. This 1870s-1880s history is largely forgotten today as the town has evolved into a sportsmen’s stop off Interstate I-15 due to its great access to the Big Hole River and surrounding national forests as well as the quite marvy Melrose Bar and Cafe, a classic western watering hole. Community institutions help to keep Melrose’s sense of itself alive in the 21st century. Its school, local firehall, the historic stone St John the Apostle Catholic Mission and the modernist styled Community Presbyterian Church are statements of stability and purpose.

Community institutions help to keep Melrose’s sense of itself alive in the 21st century. Its school, local firehall, the historic stone St John the Apostle Catholic Mission and the modernist styled Community Presbyterian Church are statements of stability and purpose.

The photo above was published in A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History, in part because of the preservation excitement over this landmark but also because it documented how the boom in Butte helped to transform the historic landscape on the “other side of the divide.” The pump station took water from the Big Hole River and pumped it over the mountains to the Butte Water Company–without the pump station, expansion of the mines and the city would have been difficult perhaps impossible in the early 20th century.

The photo above was published in A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History, in part because of the preservation excitement over this landmark but also because it documented how the boom in Butte helped to transform the historic landscape on the “other side of the divide.” The pump station took water from the Big Hole River and pumped it over the mountains to the Butte Water Company–without the pump station, expansion of the mines and the city would have been difficult perhaps impossible in the early 20th century.

In 2014, in reaction to the listing of Montana rural schools as a threatened national treasure by the National Trust of Historic Preservation, CBS Sunday Morning visited Divide School for a feature story. Teacher Judy Boyle told the Montana Standard of May 16, 2014: “The town of Divide is pretty proud of its school and they want to keep it running. We have a Post Office, the Grange and the school — and if you close the school, you basically close the town.”

In 2014, in reaction to the listing of Montana rural schools as a threatened national treasure by the National Trust of Historic Preservation, CBS Sunday Morning visited Divide School for a feature story. Teacher Judy Boyle told the Montana Standard of May 16, 2014: “The town of Divide is pretty proud of its school and they want to keep it running. We have a Post Office, the Grange and the school — and if you close the school, you basically close the town.” Divide is one of many Montana towns where residents consider their schools to the foundation for their future–helping to explain why Montanans are so passionate about their local schools.

Divide is one of many Montana towns where residents consider their schools to the foundation for their future–helping to explain why Montanans are so passionate about their local schools. Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity. Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte. The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair. The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it. Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

Willow Creek was the end of the line for both the Northern Pacific and Milwaukee Road railroads as they vied for dominance in turn of the 20th century western Gallatin County. The Northern Pacific came first with its spur line to Butte in the late 1880s then the Milwaukee arrived c. 1908. Both used the same corridor, along what is now called the Old Yellowstone Trail on some maps; the Willow Creek Road (MT 287) on others. It was a route that dated to 1864–the town cemetery, according to lore, dates to that year and Willow Creek has had a post office since 1867.

Willow Creek was the end of the line for both the Northern Pacific and Milwaukee Road railroads as they vied for dominance in turn of the 20th century western Gallatin County. The Northern Pacific came first with its spur line to Butte in the late 1880s then the Milwaukee arrived c. 1908. Both used the same corridor, along what is now called the Old Yellowstone Trail on some maps; the Willow Creek Road (MT 287) on others. It was a route that dated to 1864–the town cemetery, according to lore, dates to that year and Willow Creek has had a post office since 1867.

Across the street is the “employment center,” the Willow Creek Tool and Technology which sells its wares across the west out of its brick building from the 1910s. (Note the faded advertising sign that once greeted travelers on the Yellowstone Trail highway.)

Across the street is the “employment center,” the Willow Creek Tool and Technology which sells its wares across the west out of its brick building from the 1910s. (Note the faded advertising sign that once greeted travelers on the Yellowstone Trail highway.) The cultural side of Willow Creek is represented by several places: homes and galleries of different artists, a monthly arts festival in the summer, and two special buildings from the 1910s. The Stateler Memorial Methodist Church, c. 1915, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built from rusticated concrete blocks (from the cement factory at Three Forks) designed to resemble stone masonry, the church building is home to one of the oldest congregations (1864) in the Methodist Church in Montana. The Gothic Revival-styled sanctuary is named in honor of its founding minister Learner B. Stateler.

The cultural side of Willow Creek is represented by several places: homes and galleries of different artists, a monthly arts festival in the summer, and two special buildings from the 1910s. The Stateler Memorial Methodist Church, c. 1915, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built from rusticated concrete blocks (from the cement factory at Three Forks) designed to resemble stone masonry, the church building is home to one of the oldest congregations (1864) in the Methodist Church in Montana. The Gothic Revival-styled sanctuary is named in honor of its founding minister Learner B. Stateler. Nearby is another crucial landmark for any rural Montana community–the local school. The Willow Creek School is an excellent example of the standardized, somewhat Craftsman-styled designs used for rural Montana schools in the 1910s. Two stories of classrooms, sitting on a full basement, was a large school for its time, another reflection of the hopes of the homesteading era.

Nearby is another crucial landmark for any rural Montana community–the local school. The Willow Creek School is an excellent example of the standardized, somewhat Craftsman-styled designs used for rural Montana schools in the 1910s. Two stories of classrooms, sitting on a full basement, was a large school for its time, another reflection of the hopes of the homesteading era. Additions in form of a gym and added rooms had come to the north and the school and its lot is the town’s community center. Although so close to Three Forks, the school kept its

Additions in form of a gym and added rooms had come to the north and the school and its lot is the town’s community center. Although so close to Three Forks, the school kept its