When I carried out the 1984-1985 survey of Montana as part of the state historic preservation planning process, one resource was at the forefront of my mind–railroad passenger stations. Not only had recent scholarship by John Hudson and John Stilgoe brought new interest to the topic, there had been the recent bankruptcy of the Milwaukee Road, and the end of passenger service in large parts of the state, except along the Hi-Line of the old Great Northern Railway (where Amtrak still runs today.)

The mid-20th century standardized design for Great Northern stations at Chester on US 2.

Some of the passenger stations in the major cities had already been converted into new uses, such as restaurants, offices, and various downtown commercial uses. The lovely turn of the twentieth century stations for the Great Northern (left) and the Milwaukee Road (right) in Great Falls showed how the location of the buildings, plus their

architectural quality and the amount of available space made them perfect candidates for adaptive reuse. While the tenants have changed over the past 30 plus years, both buildings still serve as heritage anchors for the city. While success marked early adaptive reuse projects in Great Falls and Missoula, for instance, it was slow to come to Montana’s largest city–the neoclassical styled Northern Pacific depot was abandoned and

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

In the 1984-1985 I documented hundreds of railroad depots across Big Sky Country. From 2012-2015 I noted how many had disappeared–an opportunity to preserve heritage and put a well-located substantial building for the building back to work had been wasted. But I also came away with a deep appreciation of just how many types of new lives train stations could have.

Turning iconic buildings into community museums is a time-honored tradition, as you can find at the magnificent Northern Pacific station at Livingston, shown above. A handful of Montana communities have followed that tradition–I am especially glad that people in Harlowton and Wheatland County banded together to preserve the

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

But there are so many other uses–as they know in Lewistown. Already in the mid-1980s investors in Lewistown had turned the old Milwaukee Road station, shown above, into a hotel and conference center, the Yogo Inn. When I visited Lewistown in 2013 the Yogo was undergoing a facelift after 30 years as a commercial business. The town’s other

historic depot, a substantial brick building (above) from the Great Northern Railway, was a gas station, convenience mart, office building, and store, all in one.

Deer Lodge is blessed with both of its historic depots. The Milwaukee Road depot has become a church while the Northern Pacific depot became the Powell County Senior Citizens Center. Indeed, converting such a community landmark into a community center is popular in other Montana towns, such as the National Register-listed passenger station shown below in Kevin, Toole County, near the border with Canada.

One of the most encouraging trends of this century is how many families have turned depots into their homes–you can’t beat the location and the long, horizontal nature of the often-found combination depot (passenger station and luggage warehouse in same building) means that these dwellings have much in common with the later Ranch-style houses of the 1950s and 1960s.

A former Great Northern depot in Windham.

A Milwaukee Road depot turned into a home in Rosebud County.

But in my work from 2012-15 I found more and more examples of how local entrepreneurs have turned these historic buildings into businesses–from a very simple, direct conversion from depot to warehouse in Grassrange to the use of the Milwaukee Road depot in Roundup as the local electric company office.

As these last examples attest–old buildings can still serve communities, economically and gracefully. Not all historic preservation means the creation of a museum–that is the best course in only a few cases. But well-built and maintained historic buildings can be almost anything else–the enduring lesson of adaptive reuse

A resident reported on the towns decision to join the Main Street program and how a community partnership effort had been formed to guide the process, assuring me that the wonderful historic Roundup school would find a new future as a multi-purpose and use facility. That update has spurred me to share more images from this distinctive Montana town that I have enjoyed visiting for over 30 years.

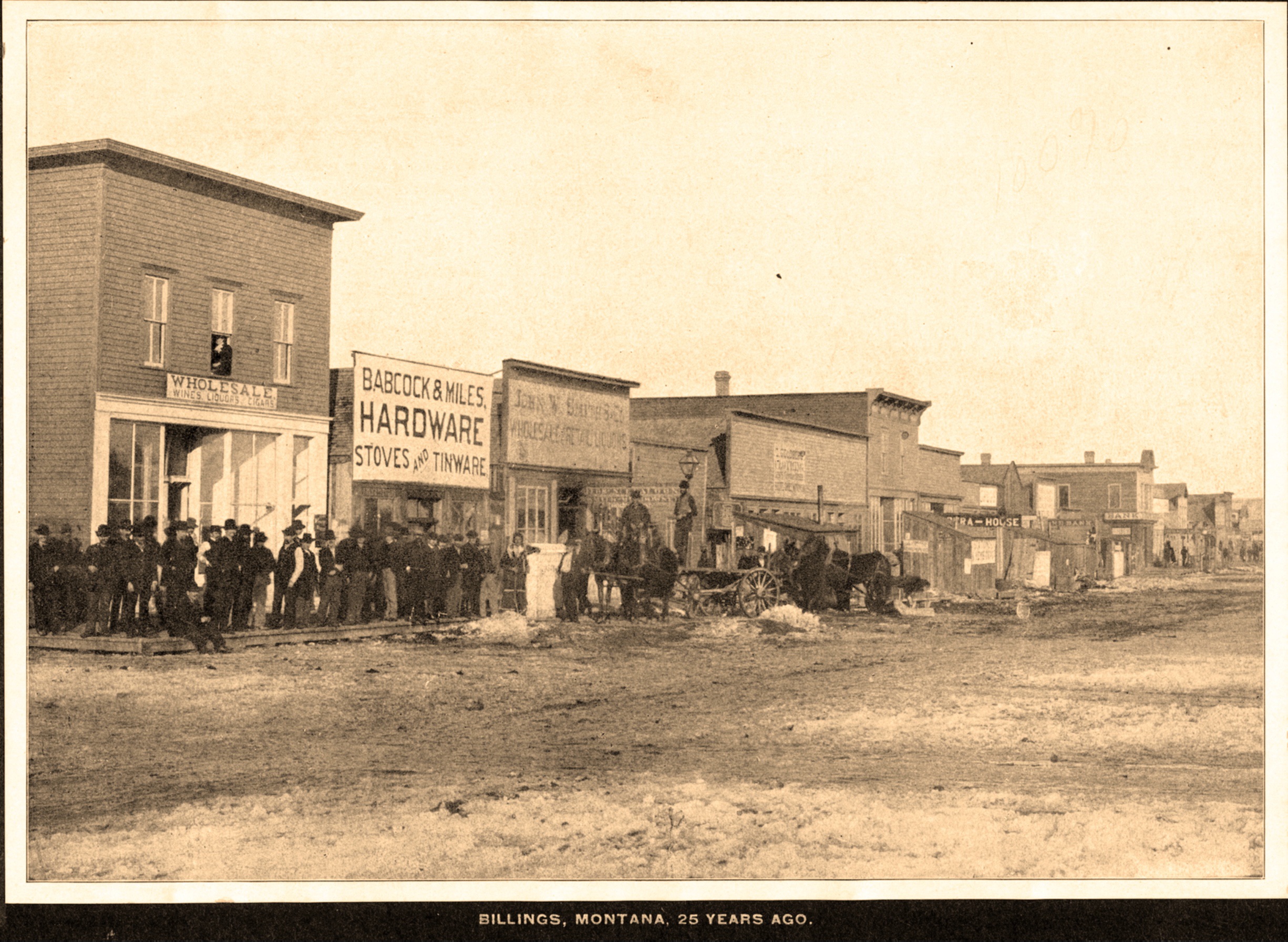

A resident reported on the towns decision to join the Main Street program and how a community partnership effort had been formed to guide the process, assuring me that the wonderful historic Roundup school would find a new future as a multi-purpose and use facility. That update has spurred me to share more images from this distinctive Montana town that I have enjoyed visiting for over 30 years. As I discussed in my earlier large posting on Roundup, it is both a railroad town on the historic mainline of the Milwaukee Road and a highway town, with a four-lane Main Street defining the commercial district. It is less than a hour’s drive north of Billings, Montana’s largest urban area. But nestled at the junction of U.S. 12 and U.S. 87, Roundup is a totally different world from booming Billings.

As I discussed in my earlier large posting on Roundup, it is both a railroad town on the historic mainline of the Milwaukee Road and a highway town, with a four-lane Main Street defining the commercial district. It is less than a hour’s drive north of Billings, Montana’s largest urban area. But nestled at the junction of U.S. 12 and U.S. 87, Roundup is a totally different world from booming Billings.

You see the difference if how false frame stores and lodge buildings from the first years of the town’s beginnings still stand, and how the commercial district is pockmarked with more stately early 20th century brick commercial blocks, whether two stories high or a mere one-story. Yet the architectural details tell you the community had ambitions. It

You see the difference if how false frame stores and lodge buildings from the first years of the town’s beginnings still stand, and how the commercial district is pockmarked with more stately early 20th century brick commercial blocks, whether two stories high or a mere one-story. Yet the architectural details tell you the community had ambitions. It

I found a place then, and still today, that was proud of its past and of its community. I visited and spoke at the county museum, which was housed in the old Catholic school and included one of county’s first homestead cabins moved to the school grounds. The nearby town park and fairgrounds (covered in an earlier post) helped to highlight just how beautiful the Musselshell River valley was at Roundup.

I found a place then, and still today, that was proud of its past and of its community. I visited and spoke at the county museum, which was housed in the old Catholic school and included one of county’s first homestead cabins moved to the school grounds. The nearby town park and fairgrounds (covered in an earlier post) helped to highlight just how beautiful the Musselshell River valley was at Roundup.

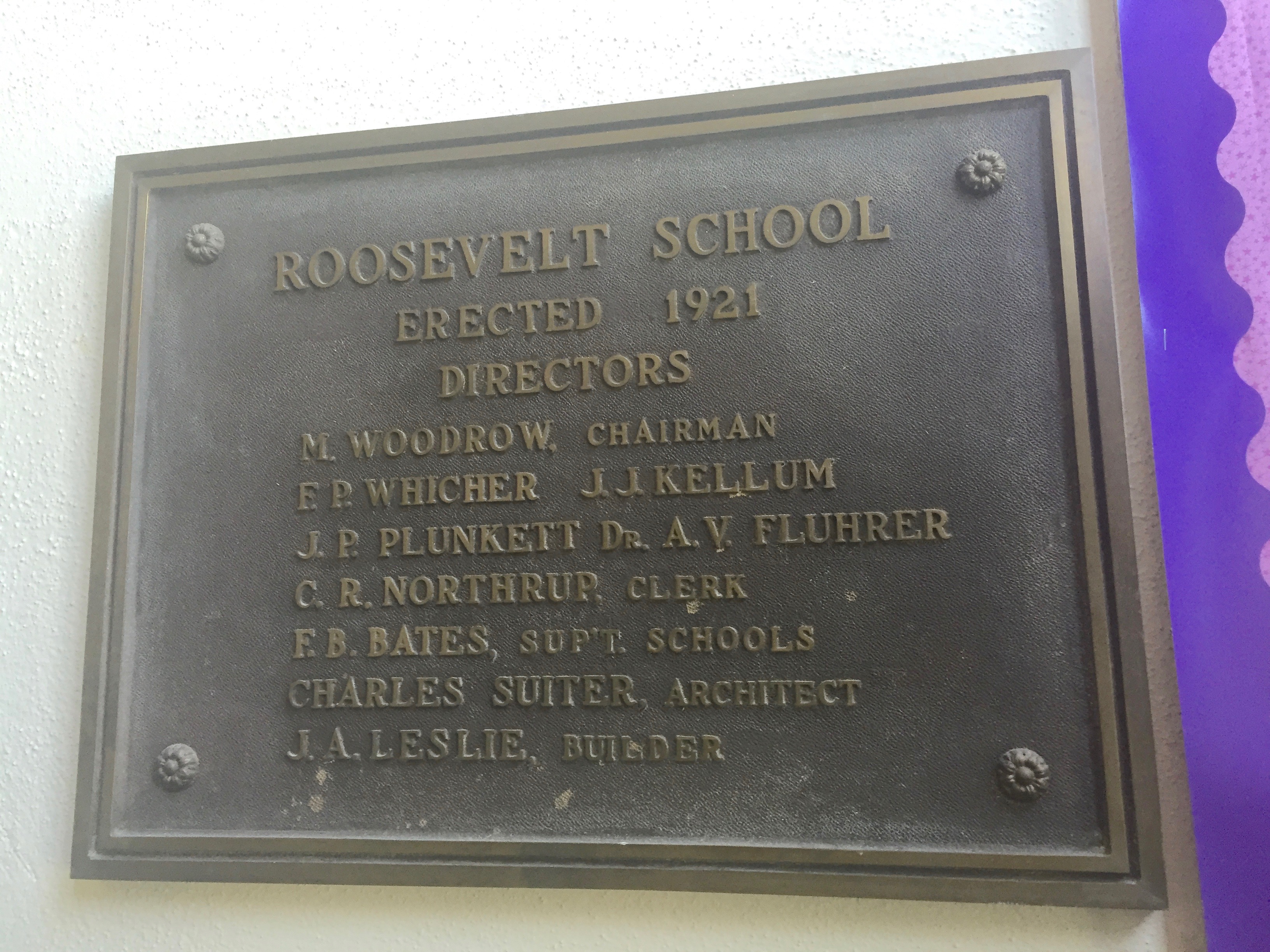

Then the public buildings–the school, the courthouse, and even the classically tinged county jail shown above–added to the town’s impressive heritage assets. Of course some buildings I ignored in the 1980s but find compelling today–like in the riverstone lined posts of the modernist Wells Fargo Bank, and the effective and efficient look of city hall.

Then the public buildings–the school, the courthouse, and even the classically tinged county jail shown above–added to the town’s impressive heritage assets. Of course some buildings I ignored in the 1980s but find compelling today–like in the riverstone lined posts of the modernist Wells Fargo Bank, and the effective and efficient look of city hall.

were so many intact details from the time of construction–built-in storage spaces, private restroom stalls, when hallway clocks ticking down the minutes in a day–the place was like a time capsule.

were so many intact details from the time of construction–built-in storage spaces, private restroom stalls, when hallway clocks ticking down the minutes in a day–the place was like a time capsule.

Intimate spaces, classroom spaces, grand public spaces. The Roosevelt School meant too much to be left to the wrecking ball, and the progress the community foundation is making there is reassuring: once again smart, effective adaptive reuse can turn a building in a sustainable heritage asset for the town. It’s worth checking out, and supporting. And it is next door to one of the state’s amazing throwback 1960s roadside

Intimate spaces, classroom spaces, grand public spaces. The Roosevelt School meant too much to be left to the wrecking ball, and the progress the community foundation is making there is reassuring: once again smart, effective adaptive reuse can turn a building in a sustainable heritage asset for the town. It’s worth checking out, and supporting. And it is next door to one of the state’s amazing throwback 1960s roadside

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors. Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Plains is the second largest town in Sanders County, noted as the home of the county fairgrounds, the center of the local agricultural economy, and like Thompson Falls a significant place along the Clark’s Fork River and the Montana Highway 200 corridor.

Plains is the second largest town in Sanders County, noted as the home of the county fairgrounds, the center of the local agricultural economy, and like Thompson Falls a significant place along the Clark’s Fork River and the Montana Highway 200 corridor.

century feel, be it in institutions, such as the local Grange above, or the continuation of the local VFW hall and bowling alley, below.

century feel, be it in institutions, such as the local Grange above, or the continuation of the local VFW hall and bowling alley, below.

The Noxon Dam was finished in 1959. It is a mile in length, 260 feet in height and 700 feet wide at its base. Its generators can power approximately 365,000 homes, making it the second-largest capacity hydroelectric facility in Montana.

The Noxon Dam was finished in 1959. It is a mile in length, 260 feet in height and 700 feet wide at its base. Its generators can power approximately 365,000 homes, making it the second-largest capacity hydroelectric facility in Montana. Today visitors can view the dam from various parking areas and short walking trails, one of which passes over the historic line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The property has interpretive signs about the history of the project as well as about the engineering of hydroelectric power.

Today visitors can view the dam from various parking areas and short walking trails, one of which passes over the historic line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The property has interpretive signs about the history of the project as well as about the engineering of hydroelectric power. Along the banks of the river/reservoir, a much more recent public park has opened–with public sculpture reminding everyone of the Native Americans who once camped along the

Along the banks of the river/reservoir, a much more recent public park has opened–with public sculpture reminding everyone of the Native Americans who once camped along the river at this place. By bringing the deep past of the region in view of the modern, this site is a new favorite place–wherever you are in Montana, and there are many modern engineering marvels–the Indians were always there first, using those same natural resources in far different ways.

river at this place. By bringing the deep past of the region in view of the modern, this site is a new favorite place–wherever you are in Montana, and there are many modern engineering marvels–the Indians were always there first, using those same natural resources in far different ways.