The vast majority of my effort to document and think about the historic landscapes of Montana lie with two time periods, 1984-85 and 2012-16. But in between those two focused periods, other projects at the Western Heritage Center in Billings brought me back to the Big Sky Country. Almost always I found a way to carve out a couple of additional days to get away from the museum and study the many layers of history, and change, in the landscape by taking black and white images as I had in 1984-85. One such trip came in 1999, at the end of the 20th century.

In Billings itself I marveled at the changes that historic preservation was bringing to the Minnesota Avenue district. The creation of an “Internet cafe” (remember those?) in the McCormick Block was a guaranteed stop.

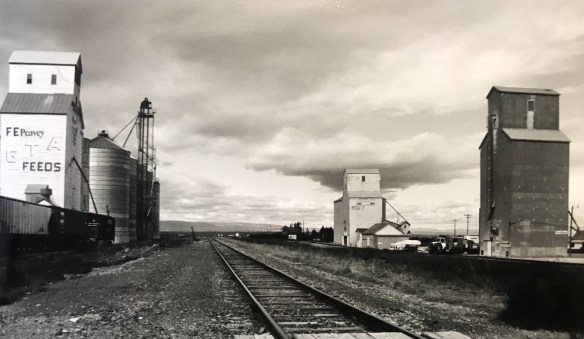

But my real goal was to jet up highways 191 and 80 to end up in Fort Benton. Along the way I had to stop at Moore, one of my favorite Central Montana railroad towns, and home to a evocative set of grain elevators.

Then a stop for lunch at the Geraldine bar and the recently restored Geraldine depot, along a historic spur of the Milwaukee Road. I have always loved a stop in this plains country town and this day was especially memorable as residents showed off what they had accomplished in the restoration. Another historic preservation plus!

Then it was Fort Benton, a National jewel seemingly only appreciated by locals, who faced an often overwhelming task for preserving and finding sustainable new uses for the riverfront buildings.

It was exciting to see the recent goal that the community eagerly discussed in 1984–rebuilding the historic fort.

A new era for public interpretation of the northern fur trade would soon open in the new century: what a change from 1984.

I beat a quick retreat back to the south, following the old Manitoba Road route along the Missouri and US Highway 87 and back via highway 89 to the Yellowstone Valley. I had to pay a quick tribute to Big Timber, and grab a brew at the Big Timber

Bar. The long Main Street in Big Timber was obviously changing–new residents and new businesses. Little did I know how much change would come in the new century.

One last detour came on the drive to see if the absolutely spectacular stone craftsmanship of the Absarokee school remained in place–it did, and still does.

My work in Tennessee had really focused in the late 1990s on historic schools: few matched the distinctive design of Absarokee. I had to see it again.

Like most trips in the 1990s to Billings I ended up in Laurel–I always felt this railroad town had a bigger part in the history of Yellowstone County than

generally accepted. The photos I took in 1999 are now striking– had any place in the valley changed more than Laurel in the 21st century?

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors. Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Libby is the seat of Lincoln County, a typical railroad town along the historic Great Northern Railway corridor. The image above is from the town’s railroad depot, the symbolic beginning of town, from which runs a long main street of businesses, reflecting the T-plan town design, where the long railroad corridor defines the top of the T and the main street forms the stem of the T.

Libby is the seat of Lincoln County, a typical railroad town along the historic Great Northern Railway corridor. The image above is from the town’s railroad depot, the symbolic beginning of town, from which runs a long main street of businesses, reflecting the T-plan town design, where the long railroad corridor defines the top of the T and the main street forms the stem of the T.

courthouse received a totally new front, in a contemporary style, in the 1970s as the town and county expanded in the wake of the federal spending in constructing Libby Dam. The rectangular blockiness, flat roof, and band of windows set within a symmetrical facade makes the courthouse one of the state’s best designs for a rural public building in the late 20th century.

courthouse received a totally new front, in a contemporary style, in the 1970s as the town and county expanded in the wake of the federal spending in constructing Libby Dam. The rectangular blockiness, flat roof, and band of windows set within a symmetrical facade makes the courthouse one of the state’s best designs for a rural public building in the late 20th century. I liked all of those things about Libby in 1984. Imagine my shock and disappointment to learn, as everyone else did, that Libby was one of the poisoned places in the west. In 1919, vermiculite, a natural material that contains asbestos, had been discovered outside of town, and the mines were still operating, producing 80 percent of the vermiculite in the world, under the control of the W.R. Grace company. Residue from the mines had been used in local yards and buildings for decades, a fact that was not known when I visited the town for the state historic preservation plan. When the discovery of the danger became public, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency entered into the fray in 1999, it was already too late for many residents. A federal Superfund project began, and did not conclude its work until 2015, spending some $425 million. Then in 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency announced a public health emergency, spending another $130 million to help residents and to leave a new health infrastructure in place. In a generation, Libby had been turned inside out. EPA announced in 2016 that the cleanup would continue to 2018, and that the project was the longest in the agency’s history.

I liked all of those things about Libby in 1984. Imagine my shock and disappointment to learn, as everyone else did, that Libby was one of the poisoned places in the west. In 1919, vermiculite, a natural material that contains asbestos, had been discovered outside of town, and the mines were still operating, producing 80 percent of the vermiculite in the world, under the control of the W.R. Grace company. Residue from the mines had been used in local yards and buildings for decades, a fact that was not known when I visited the town for the state historic preservation plan. When the discovery of the danger became public, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency entered into the fray in 1999, it was already too late for many residents. A federal Superfund project began, and did not conclude its work until 2015, spending some $425 million. Then in 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency announced a public health emergency, spending another $130 million to help residents and to leave a new health infrastructure in place. In a generation, Libby had been turned inside out. EPA announced in 2016 that the cleanup would continue to 2018, and that the project was the longest in the agency’s history.

Despite the disaster, I saw many signs that Libby residents were determined to remain and rebuild their community. One of the most powerful examples is the conversion of one of the town’s historic schools into a new community arts center as well as school administration offices.

Despite the disaster, I saw many signs that Libby residents were determined to remain and rebuild their community. One of the most powerful examples is the conversion of one of the town’s historic schools into a new community arts center as well as school administration offices.

The asbestos crisis was a terrible disaster for Libby–yet residents refused to let it define their future. There are past accomplishments to acknowledge, an active railroad depot to cherish, a beautiful river and lake, the mountains all around, as celebrated in this public art mural on a downtown building. This place is here to stay, and the historic built environment is a large part of it.

The asbestos crisis was a terrible disaster for Libby–yet residents refused to let it define their future. There are past accomplishments to acknowledge, an active railroad depot to cherish, a beautiful river and lake, the mountains all around, as celebrated in this public art mural on a downtown building. This place is here to stay, and the historic built environment is a large part of it.

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed.

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed. Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

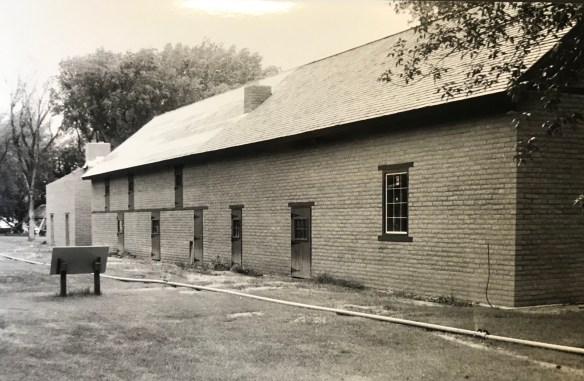

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

of the Milwaukee Road in 1980, the town has steadily lost population-2oo less residents in 2015 compared to my first visit 30 years earlier. Never a large place–the town’s top population was 1242 residents in 1960–Superior has several landmark buildings from its railroad days but only one has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

of the Milwaukee Road in 1980, the town has steadily lost population-2oo less residents in 2015 compared to my first visit 30 years earlier. Never a large place–the town’s top population was 1242 residents in 1960–Superior has several landmark buildings from its railroad days but only one has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. That one place, the Superior School, is spectacular and its tall central tower has long served as a community beacon. Built 1915-16 by contractor Charles Augustine, the high school reflected Colonial Revival style, and later community growth led to wing additions in 1925, shown above, and in 1947.

That one place, the Superior School, is spectacular and its tall central tower has long served as a community beacon. Built 1915-16 by contractor Charles Augustine, the high school reflected Colonial Revival style, and later community growth led to wing additions in 1925, shown above, and in 1947. Another Colonial Revival-styled public building is the Mineral County Courthouse, 1920, complete with its colonial-inspired cupola. Mineral County was created in 1914. This building is more complete rural interpretation of Colonial Revival style than the school.

Another Colonial Revival-styled public building is the Mineral County Courthouse, 1920, complete with its colonial-inspired cupola. Mineral County was created in 1914. This building is more complete rural interpretation of Colonial Revival style than the school.

The historic Strand Theater (c. 1915) operated in 1984 but closed in 2013 and remained shuttered when I visited in 2015, no doubt a victim of not only the home theatre phenomenon but also the switch to digital delivery of movies in this decade. This theatre, however, is a rare and important building from the homesteading era of the 1910s.

The historic Strand Theater (c. 1915) operated in 1984 but closed in 2013 and remained shuttered when I visited in 2015, no doubt a victim of not only the home theatre phenomenon but also the switch to digital delivery of movies in this decade. This theatre, however, is a rare and important building from the homesteading era of the 1910s. From the same decade, the historic Masonic Mountain Lodge still operates, serving as another community outlet and center in Superior. The town’s population height in the 1960s led to the construction of the institutional Ranch-style of the Superior High School, one of two bits of mid-century modernism in Superior.

From the same decade, the historic Masonic Mountain Lodge still operates, serving as another community outlet and center in Superior. The town’s population height in the 1960s led to the construction of the institutional Ranch-style of the Superior High School, one of two bits of mid-century modernism in Superior.

The other example dates to 1958 and represents yet another example of modern design in a rural Catholic Church in Montana. St Mary Queen of Heaven Catholic Church is also a

The other example dates to 1958 and represents yet another example of modern design in a rural Catholic Church in Montana. St Mary Queen of Heaven Catholic Church is also a Ranch-styled inspired design, although its stand-alone but visually and physically linked low bell tower is unique compared to other Montana Catholic churches from this era.

Ranch-styled inspired design, although its stand-alone but visually and physically linked low bell tower is unique compared to other Montana Catholic churches from this era. The church is Superior’s best contribution to Montana modernism and complements well the Victorian influence found at the town’s historic United Methodist Church, built almost 50 years earlier. Note that both churches have low bell towers.

The church is Superior’s best contribution to Montana modernism and complements well the Victorian influence found at the town’s historic United Methodist Church, built almost 50 years earlier. Note that both churches have low bell towers.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

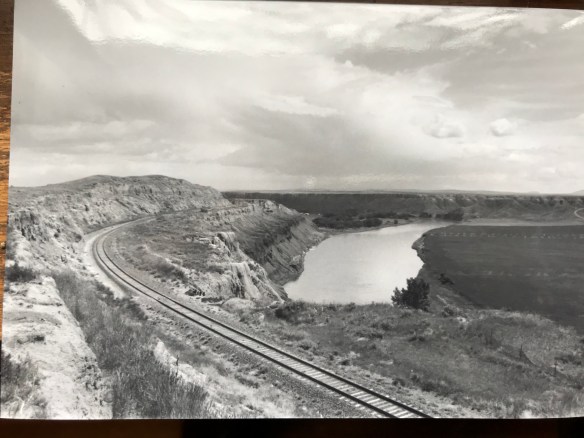

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road. The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

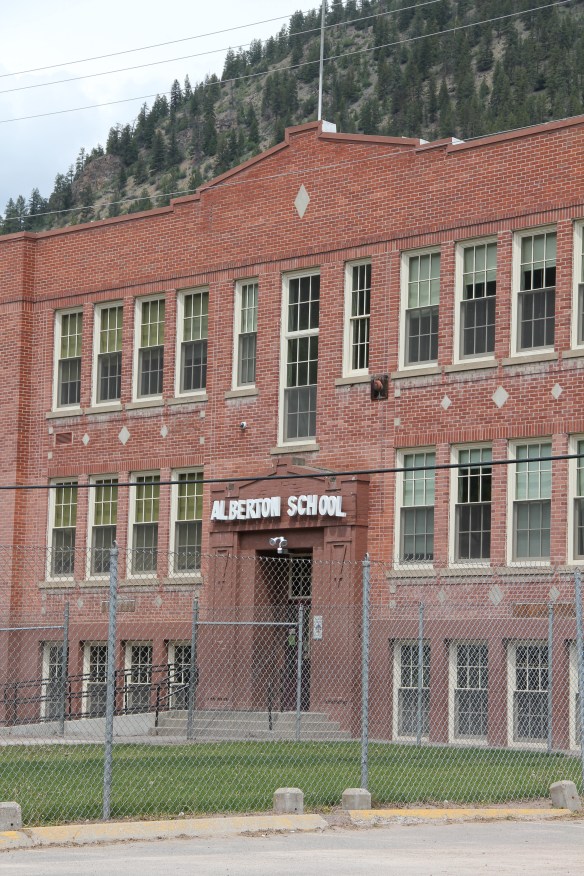

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work.

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism.

I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism. The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings. The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

The Clark’s Fork River and transportation through the valleys and over the Rocky Mountains lie at the core of Missoula’s early history. Captain John Mullan blazed his road through here immediately before the Civil War, and a Mullan Road marker is downtown.

The Clark’s Fork River and transportation through the valleys and over the Rocky Mountains lie at the core of Missoula’s early history. Captain John Mullan blazed his road through here immediately before the Civil War, and a Mullan Road marker is downtown. White settlement first arrived in the initial territorial years and a sawmill was the first major business. As a river crossroads town, Missoula grew, and then became a permanent dot on the federal map with the arrival of Fort Missoula, established in 1877. The fort, largely neglected when I conducted my work for the state historic preservation plan in 1984, is now a regional heritage center.

White settlement first arrived in the initial territorial years and a sawmill was the first major business. As a river crossroads town, Missoula grew, and then became a permanent dot on the federal map with the arrival of Fort Missoula, established in 1877. The fort, largely neglected when I conducted my work for the state historic preservation plan in 1984, is now a regional heritage center.

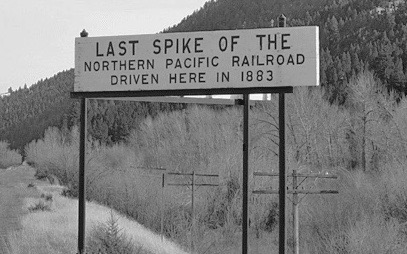

Built in 1901, the Northern Pacific passenger station is an impressive example of Renaissance Revival style, designed by the architectural firm of Reed and Stem, and symbolized the turn of the century dominance of the railroad over the region’s transportation and the importance of Missoula to the railroad as a major train yard. The station, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, stands at the historic “top” of downtown Missoula, which at its bare bones has the classic T-plan of a railroad hub of the late 19th century. The Northern Pacific tracks and related railroad warehouses are the top of the “T” stretching in both directions with Interstate I-90 crossing the river bluffs to the northeast. Two reminders of the historic railroad traffic are adjacent to the station–a steam Northern Pacific engine and a diesel Burlington Northern engine.

Built in 1901, the Northern Pacific passenger station is an impressive example of Renaissance Revival style, designed by the architectural firm of Reed and Stem, and symbolized the turn of the century dominance of the railroad over the region’s transportation and the importance of Missoula to the railroad as a major train yard. The station, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, stands at the historic “top” of downtown Missoula, which at its bare bones has the classic T-plan of a railroad hub of the late 19th century. The Northern Pacific tracks and related railroad warehouses are the top of the “T” stretching in both directions with Interstate I-90 crossing the river bluffs to the northeast. Two reminders of the historic railroad traffic are adjacent to the station–a steam Northern Pacific engine and a diesel Burlington Northern engine.

The Milwaukee was not to be out-done by the Northern Pacific when it arrived in Missoula in 1908. Railroad architect J. J. Lindstrand gave the line a fashionable Misson-style passenger station and offices, which opened in 1910. It too is listed in the National Register. Like the company’s stations in Great Falls and Butte, built approximately at the same time, the station has a tall tower that commanded the city’s early 20th century skyline, and made the depot easy to find. Located dramatically along the Clark’s Fork River, the arrival of the railroad and the construction of the depot led to a new frenzy of building on South Higgins Street, and a good many of those one-story and two-story buildings remain in use today.

The Milwaukee was not to be out-done by the Northern Pacific when it arrived in Missoula in 1908. Railroad architect J. J. Lindstrand gave the line a fashionable Misson-style passenger station and offices, which opened in 1910. It too is listed in the National Register. Like the company’s stations in Great Falls and Butte, built approximately at the same time, the station has a tall tower that commanded the city’s early 20th century skyline, and made the depot easy to find. Located dramatically along the Clark’s Fork River, the arrival of the railroad and the construction of the depot led to a new frenzy of building on South Higgins Street, and a good many of those one-story and two-story buildings remain in use today.

Missoula County has grown, a lot, since my state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985, especially in the county seat of Missoula and surrounding suburbs. Yet Missoula County still has several spectacular rural drives, like Montana Highway 83 above at Condon, along with distinctive country towns. This post will share some of my favorites.

Missoula County has grown, a lot, since my state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985, especially in the county seat of Missoula and surrounding suburbs. Yet Missoula County still has several spectacular rural drives, like Montana Highway 83 above at Condon, along with distinctive country towns. This post will share some of my favorites.

The Condon Community Center and adjacent Swan Valley Community Library serve as additional hubs for those living along the lakes and mountains of northeast Missoula County. Both buildings are excellent examples of mid-20th century Rustic style–a look that, in different variations, dominates the Highway 35 corridor.

The Condon Community Center and adjacent Swan Valley Community Library serve as additional hubs for those living along the lakes and mountains of northeast Missoula County. Both buildings are excellent examples of mid-20th century Rustic style–a look that, in different variations, dominates the Highway 35 corridor.

Condon is also the base for the Condon Work Center, home to the Great Northern Fire Crew, of the Flathead National Forest. Here you can take a mile-long Swan Ecosystem Trail and learn of the diversity of life in this national forest region.

Condon is also the base for the Condon Work Center, home to the Great Northern Fire Crew, of the Flathead National Forest. Here you can take a mile-long Swan Ecosystem Trail and learn of the diversity of life in this national forest region. South of Condon on Montana Highway 83 is Seeley Lake–a place that certainly has boomed in the last 30 years–witness the improved highway, new businesses, and population that has increased over 60 percent since my last visit in 1992. Yet it still had places rooted in the community’s earlier history such as the Sullivan Memorial Community Hall–a good example of mid-20th century Rustic style.

South of Condon on Montana Highway 83 is Seeley Lake–a place that certainly has boomed in the last 30 years–witness the improved highway, new businesses, and population that has increased over 60 percent since my last visit in 1992. Yet it still had places rooted in the community’s earlier history such as the Sullivan Memorial Community Hall–a good example of mid-20th century Rustic style. And it had added one of my favorite bits of roadside architecture in this part of Montana: the Chicken Coop Restaurant as well as opening a new Seeley Lake Historical Museum and Chamber of Commerce office at a spectacular highway location just outside of town.

And it had added one of my favorite bits of roadside architecture in this part of Montana: the Chicken Coop Restaurant as well as opening a new Seeley Lake Historical Museum and Chamber of Commerce office at a spectacular highway location just outside of town.

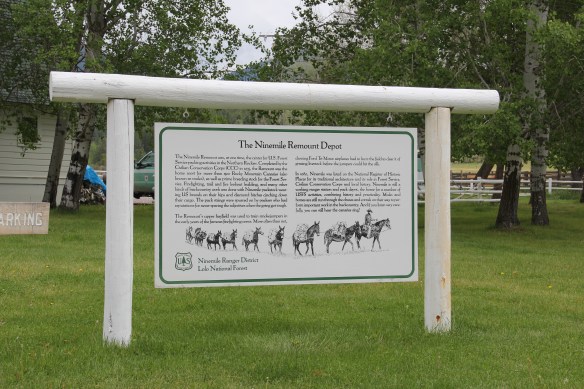

I don’t recall even thinking about the forest service facility, but here was an entire complex devoted to the forest service’s use of mules and horses before the days of the ATV that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The remount depot is an interesting

I don’t recall even thinking about the forest service facility, but here was an entire complex devoted to the forest service’s use of mules and horses before the days of the ATV that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The remount depot is an interesting

The name Frenchtown dates to 1868 and is a reference to a number of French Canadians who moved here in the early settlement period. A National Register-listed church, the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (1884) marks that first generation of settlers. Its classical-tinged cupola has long been the town’s most famous landmark.

The name Frenchtown dates to 1868 and is a reference to a number of French Canadians who moved here in the early settlement period. A National Register-listed church, the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (1884) marks that first generation of settlers. Its classical-tinged cupola has long been the town’s most famous landmark. The Milwaukee Road built through here in 1907-1908 and there remains a handful of historic business buildings from the time of the Milwaukee boom. There is one landmark

The Milwaukee Road built through here in 1907-1908 and there remains a handful of historic business buildings from the time of the Milwaukee boom. There is one landmark

another roadside landmark–the Bucksnort Bar, just further evidence to add to the Chicken Coop and the Alcan that you won’t go hungry if you explore the small towns of Missoula County.

another roadside landmark–the Bucksnort Bar, just further evidence to add to the Chicken Coop and the Alcan that you won’t go hungry if you explore the small towns of Missoula County.