Milk River Irrigation Project Ditch at Dodson, Phillips County

In today’s New York Times (June 15, 2020), Montana Jim Robbins reported on the looming disaster facing Montana’s northern states if the St. Mary’s canal, which recently collapsed, is not repaired. The informative, insightful story focuses on the beginnings of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s Milk River Irrigation Project, its pathway through southern Alberta, and its emergence in central Montana’s Hill County. It included several wonderful images of Havre, the seat of Hill County, and discussed the wide-ranging disaster faced by ranchers and small towns along the Hi-Line if the ditch did not get its long overdue repairs–to the tune of $200 million.

The Great Northern, the Milk River Project, and original U.S. 2 at Tampico

Robbins’ story immediately took my mind back to my travels throughout the Milk River Valley, from Hill County to Valley County, in 2013. The story of how modern transportation and engineering combined to transform the northern plains is so fundamental to the region’s history, yet it remains a story seldom told (another reason Robbins’ New York Times story matters). The image above represents the forces that led to the settlement and development of the Milk River Valley. Taken outside of the village of Tampico in Valley County, it centers the ditch between the two transportation systems–the Great Northern Railway on the left and the original route of U.S. Highway 2 on the right– that served the settlers drawn by the water. The image below shows the village of Tampico from the perspective of the ditch–the place would not exist without the ditch.

One of the very few historical markers in Montana that touches on the state’s irrigation history focuses about a historic bridge that once stood nearby at Tampico.

One of the very few historical markers in Montana that touches on the state’s irrigation history focuses about a historic bridge that once stood nearby at Tampico.

Large man-made lakes capture water to reserve it for use throughout the growing season. The images above are of Fresno Reservoir, on a rainy morning, in Hill County. While the two images below are of Nelson Reservoir, on a typically bright sunny day, many miles downstream in Phillips County.

Large man-made lakes capture water to reserve it for use throughout the growing season. The images above are of Fresno Reservoir, on a rainy morning, in Hill County. While the two images below are of Nelson Reservoir, on a typically bright sunny day, many miles downstream in Phillips County.

The Milk River Project shapes so much of the Hi-Line, it has become just part of the scenery. I wonder how many travelers along U.S. Highway 2 in Phillips County even notice or consider the constant presence of the ditch along their route.

The Milk River Project shapes so much of the Hi-Line, it has become just part of the scenery. I wonder how many travelers along U.S. Highway 2 in Phillips County even notice or consider the constant presence of the ditch along their route.

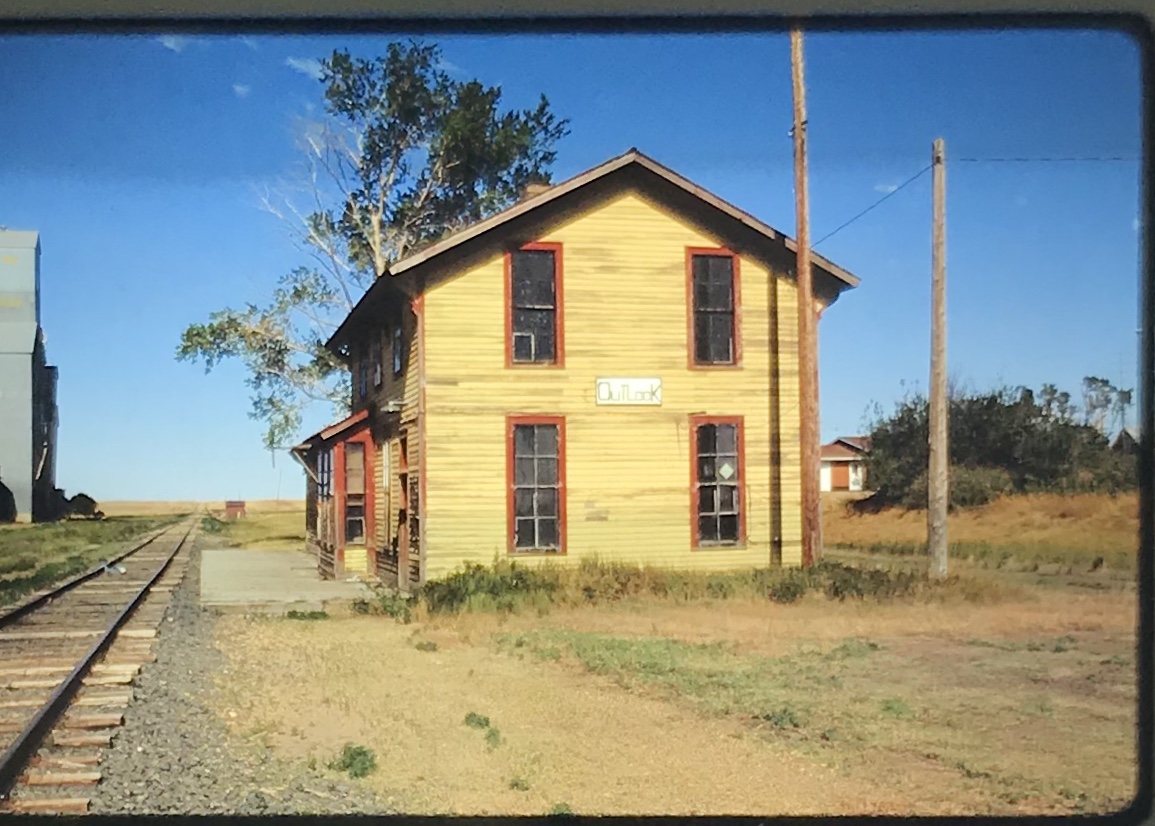

Not only are their scattered small towns along the Milk River Project, early agricultural institutions are often centered on the project. A great example is the Phillips County Fairgrounds, outside of Dodson, and the question may be well posed–why there? Dodson

is a tiny place, almost 20 miles from the county seat of Malta. But at the time of the Milk River Project, Dodson was vital; the ditch neatly divided the town into two halves, and a major diversion dam was just west of town. Here was a perfect place, at the turn of the century, for a fairgrounds. And it is a gorgeous historic fairgrounds.

is a tiny place, almost 20 miles from the county seat of Malta. But at the time of the Milk River Project, Dodson was vital; the ditch neatly divided the town into two halves, and a major diversion dam was just west of town. Here was a perfect place, at the turn of the century, for a fairgrounds. And it is a gorgeous historic fairgrounds.

My first encounter with the Milk River Project and the beautiful valley it serves came in February 1984 when Eleanor Clack took me on a tour of the bison kill historic site just west of downtown Havre. It remains an excellent place to see how the waters of the Milk have nurtured countless generations of peoples who called this place home.

Just last week I posted about two other Milk River Project towns–Lohman and Zurich–in Blaine County. My next post will continue this second look at the Milk River Project as I revisit Chinook, the Blaine County seat, where the ditch once again is almost everywhere, but rarely given a second thought.

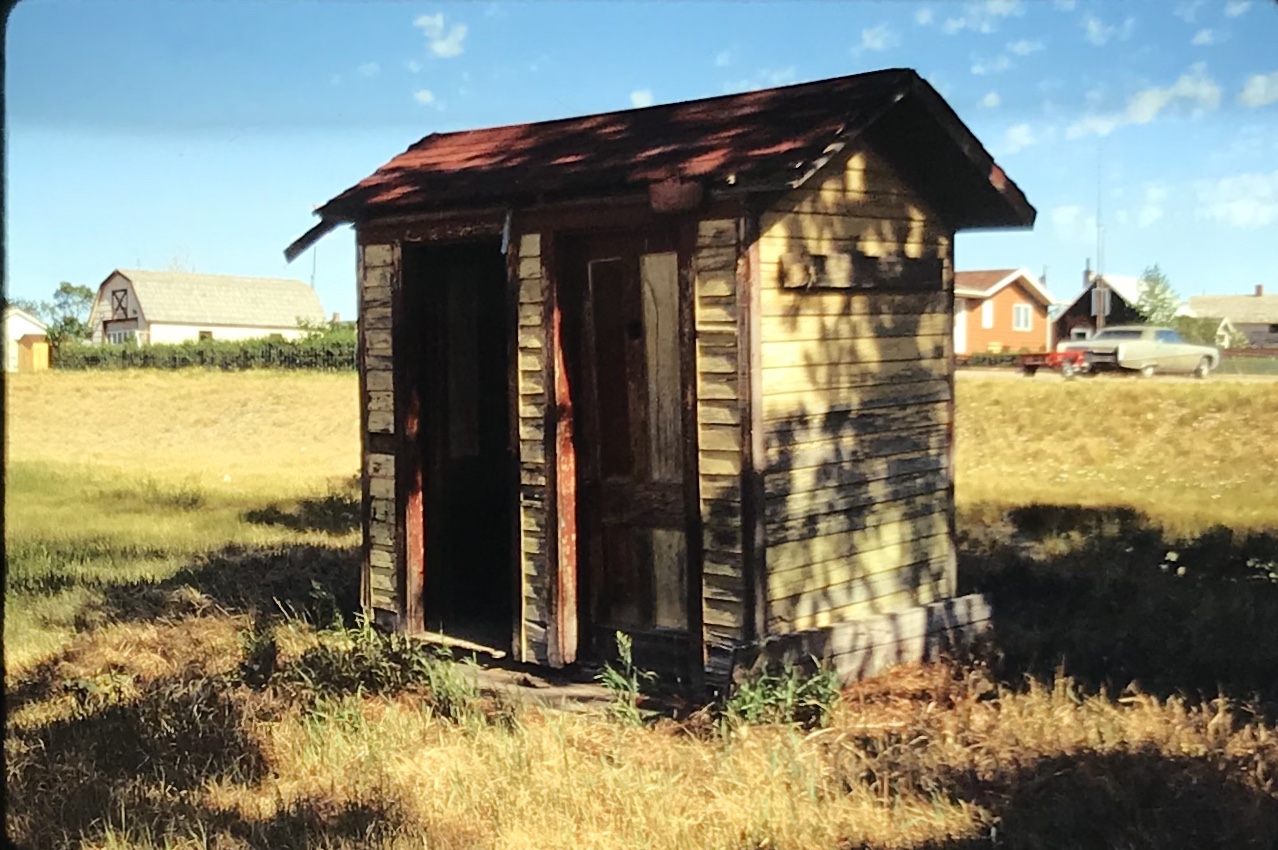

Lehman, west of Chinook adjacent to both the Milk River and U.S. Highway 2, has almost totally disappeared as a place along the tracks. What is left of the town–this deteriorating commercial building in 2013–might even be gone today.

Lehman, west of Chinook adjacent to both the Milk River and U.S. Highway 2, has almost totally disappeared as a place along the tracks. What is left of the town–this deteriorating commercial building in 2013–might even be gone today.

buildings, the rather different design of the post office from the 1960s and the vernacular Gothic beauty of the historic Methodist Church, especially the Victorian brackets of its bell tower.

buildings, the rather different design of the post office from the 1960s and the vernacular Gothic beauty of the historic Methodist Church, especially the Victorian brackets of its bell tower.

modern style for many Catholic churches in eastern Montana. The Culbertson church is a good example of that pattern. Another church that belongs to the modern design era of the 20th century is Trinity Lutheran Church, especially as this distinguished building expanded over the decades to meet its congregation’s needs.

modern style for many Catholic churches in eastern Montana. The Culbertson church is a good example of that pattern. Another church that belongs to the modern design era of the 20th century is Trinity Lutheran Church, especially as this distinguished building expanded over the decades to meet its congregation’s needs.

The earlier homes in the district are mostly Victorian in style and form, like the dwellings at 707 N. Meade (below) and 709 N. Kendrick (second below), the most Queen Anne style dwelling that I recorded in 1988 in Glendive.

The earlier homes in the district are mostly Victorian in style and form, like the dwellings at 707 N. Meade (below) and 709 N. Kendrick (second below), the most Queen Anne style dwelling that I recorded in 1988 in Glendive.

A good bit of the historic machine shops (above) still operated in 1988. The depot and railroad offices still dominated the Merrill Avenue business district (below).

A good bit of the historic machine shops (above) still operated in 1988. The depot and railroad offices still dominated the Merrill Avenue business district (below).

My favorite Merrill Avenue business was the wonderful Art Moderne style of the Luhaven Bar (below). You gots love the black carrera glass and glass block entrance.

My favorite Merrill Avenue business was the wonderful Art Moderne style of the Luhaven Bar (below). You gots love the black carrera glass and glass block entrance.

But my favorite modernist building was the First National Bank, which was later converted to the town’s public library.

But my favorite modernist building was the First National Bank, which was later converted to the town’s public library. Next posting will include homes from the town’s residential district from the early 20th century to the mid-century as I continue a look back to the Yellowstone River and its towns in 1988.

Next posting will include homes from the town’s residential district from the early 20th century to the mid-century as I continue a look back to the Yellowstone River and its towns in 1988.