It has been five years since I revisited the historic built environment of northeast Montana. My last posting took a second look at Wolf Point, the seat of Roosevelt County. I thought a perfect follow-up would be second looks at the different county seats of the region–a part of the Treasure State that I have always enjoyed visiting, and would strongly encourage you to do the same.

Grain elevators along the Glasgow railroad corridor.

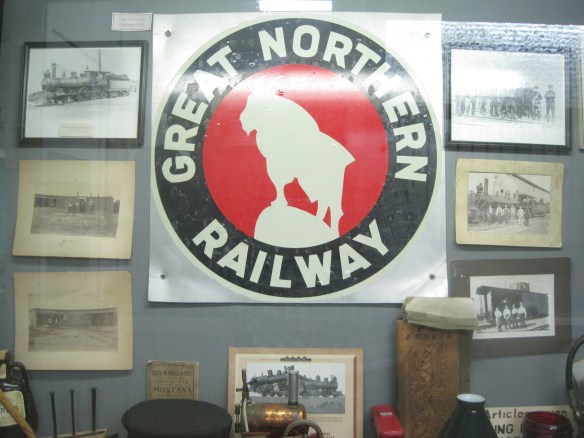

Like Wolf Point, Glasgow is another of the county seats created in the wake of the Manitoba Road/Great Northern Railway building through the state in the late 1880s. Glasgow is the seat of Valley County. The courthouse grounds include not only the modernist building above from 1973 but a WPA-constructed courthouse annex/ public building from 1939-1940 behind the courthouse.

The understated WPA classic look of this building fits into the architectural legacies of Glasgow. My first post about the town looked at its National Register buildings and the blending of classicism and modernism. Here I want to highlight other impressive properties that I left out of the original Glasgow entry. St. Michael’s Episcopal Church is an excellent late 19th century of Gothic Revival style in Montana.

The town has other architecturally distinctive commercial buildings that document its transition from late Victorian era railroad town to am early 20th century homesteading boom town.

The fact that these buildings are well-kept and in use speaks to the local commitment to stewardship and effective adaptive reuse projects. As part of Glasgow’s architectural legacy I should have said more about its Craftsman-style buildings, beyond the National

Register-listed Rundle Building. The Rundle is truly eye-catching but Glasgow also has a Mission-styled apartment row and then its historic Masonic Lodge.

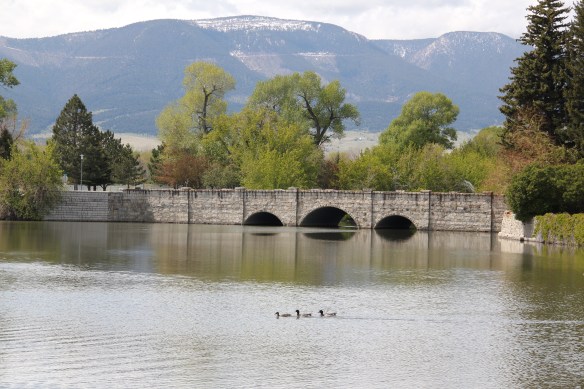

I have always been impressed with the public landscapes of Glasgow, from the courthouse grounds to the city-county library (and its excellent local history collection)

and on to Valley County Fairgrounds which are located on the boundaries of town.

Another key public institution is the Valley County Pioneer Museum, which proudly emphasizes the theme of from dinosaur bones to moon walk–just see its entrance.

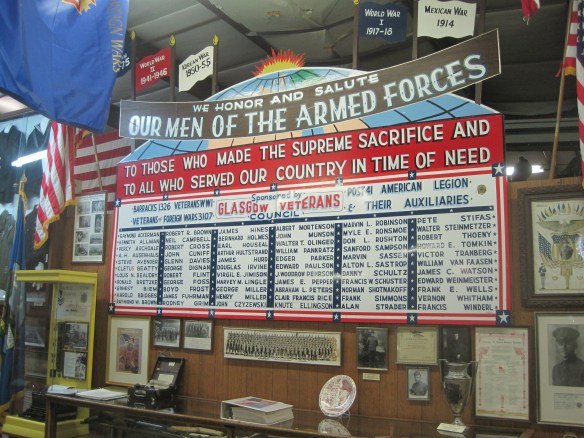

The museum was a fairly new institution when I first visited in 1984 and local leaders proudly took me through the collection as a way of emphasizing what themes and what places they wanted to be considered in the state historic preservation plan. Then I spoke with the community that evening at the museum. Not surprisingly then, the museum has ever since been a favorite place. Its has grown substantially in 35 years to include buildings and other large items on a lot adjacent to the museum collections. I have earlier discussed its collection of Thomas Moleworth furniture–a very important bit of western material culture from the previous town library. In the images below, I want to suggest its range–from the deep Native American past to the railroad era to the county’s huge veteran story and even its high school band and sports history.

A new installation, dating to the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial of 2003, is a mural depicting the Corps of Discovery along the Missouri River in Valley County. The mural is signed by artist Jesse W. Henderson, who also identifies himself as a Chippewa-Cree. The mural is huge, and to adequately convey its details I have divided my images into the different groups of people Henderson interprets in the mural.

The Henderson mural, together with the New Deal mural of the post office/courthouse discussed in my first Glasgow posting (below is a single image of that work by Forrest

Hill), are just two of the reasons to stop in Glasgow–it is one of those county seats where I discover something new every time I travel along U.S. Highway 2.

As I would come to find out, on two return trips here in 1984, the town was much more than that, it was a true bordertown between two nations and two cultures. The two trips came about from, first, a question about a public building’s eligibility for the National Register, and, second, the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, where such obvious landmarks as the National Hotel and Eureka passenger depot were noted. Thirty

As I would come to find out, on two return trips here in 1984, the town was much more than that, it was a true bordertown between two nations and two cultures. The two trips came about from, first, a question about a public building’s eligibility for the National Register, and, second, the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, where such obvious landmarks as the National Hotel and Eureka passenger depot were noted. Thirty

years later I was pleased to see the National Hotel in much better condition but dismayed to see the Great Northern passenger station–a classic example of its early 20th century standardized designs–is far worse condition that it had been in 1984.

years later I was pleased to see the National Hotel in much better condition but dismayed to see the Great Northern passenger station–a classic example of its early 20th century standardized designs–is far worse condition that it had been in 1984. Otherwise, Eureka has done an impressive job of holding together its historic core of downtown one and two-story commercial buildings. In 1995, owners had the Farmers and Merchants State Bank, built in 1907, placed in the National Register. Walking the town, however, you see the potential of a historic district of this turn of the 20th century place.

Otherwise, Eureka has done an impressive job of holding together its historic core of downtown one and two-story commercial buildings. In 1995, owners had the Farmers and Merchants State Bank, built in 1907, placed in the National Register. Walking the town, however, you see the potential of a historic district of this turn of the 20th century place.

Located on a hill perched over the town, the building was obviously a landmark–but in 1984 it also was just 42 years old, and that meant it needed to have exceptional significance to the local community to merit listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Eureka had been a logging community, and the depression hit hard. The new building not only reflected community pride but also local craftsmanship, and it became a

Located on a hill perched over the town, the building was obviously a landmark–but in 1984 it also was just 42 years old, and that meant it needed to have exceptional significance to the local community to merit listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Eureka had been a logging community, and the depression hit hard. The new building not only reflected community pride but also local craftsmanship, and it became a foundation for community resurgence in the decades to come. The building was listed in 1985, and was the first to have my name attached to it, working with Sally Steward of the local historical society. But credit has to go to Pat Bick and especially Marcella Sherfy of the State Historic Preservation Office for urging me to take it on, and to guide me through the maze of the National Register process. Today, it has experienced an adaptive reuse and serves as a rustic log furniture store.

foundation for community resurgence in the decades to come. The building was listed in 1985, and was the first to have my name attached to it, working with Sally Steward of the local historical society. But credit has to go to Pat Bick and especially Marcella Sherfy of the State Historic Preservation Office for urging me to take it on, and to guide me through the maze of the National Register process. Today, it has experienced an adaptive reuse and serves as a rustic log furniture store. During those visits in 1984 I also held a public meeting in Eureka for the state historic preservation plan, where I learned about the Tobacco Valley Historical Society and its efforts to preserve buildings destined for the chopping block through its museum village on the southern edge of town. Here the community gathered the Great Northern depot (1903) of Rexford, the same town’s 1926 Catholic Church, the Mt. Roberts lookout tower, the Fewkes Store, and a U.S. Forest Service big Creek Cabin from 1926.

During those visits in 1984 I also held a public meeting in Eureka for the state historic preservation plan, where I learned about the Tobacco Valley Historical Society and its efforts to preserve buildings destined for the chopping block through its museum village on the southern edge of town. Here the community gathered the Great Northern depot (1903) of Rexford, the same town’s 1926 Catholic Church, the Mt. Roberts lookout tower, the Fewkes Store, and a U.S. Forest Service big Creek Cabin from 1926.

Montana Highway 141 cuts north from Avon On U. S. Highway 12 to halfway between the towns of Ovando and Lincoln on Montana Highway 200. Its is high mountains prairie travel at its best, although the height of ranching along this route disappeared a while back. About 12-13 miles north of Avon you cross into the Nevada Creek drainage, which has long watered the land, enhanced after the New Deal added the Nevada Creek earthen dam that created Nevada Creek Reservoir in 1938.

Montana Highway 141 cuts north from Avon On U. S. Highway 12 to halfway between the towns of Ovando and Lincoln on Montana Highway 200. Its is high mountains prairie travel at its best, although the height of ranching along this route disappeared a while back. About 12-13 miles north of Avon you cross into the Nevada Creek drainage, which has long watered the land, enhanced after the New Deal added the Nevada Creek earthen dam that created Nevada Creek Reservoir in 1938.

Along the east banks of the lake are remnants of the Fitzpatrick Ranch, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I highlighted the property in my book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986). Jimmy Isbel established the property in 1872,

Along the east banks of the lake are remnants of the Fitzpatrick Ranch, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I highlighted the property in my book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986). Jimmy Isbel established the property in 1872,

Thirty years ago, this significant collection of vernacular buildings was in good condition, but the years since have been hard on the property, and the complex now needs serious preservation attention. The loss of the roof on the log barn, and the general poor condition of the roofs of the outbuildings are major concerns.

Thirty years ago, this significant collection of vernacular buildings was in good condition, but the years since have been hard on the property, and the complex now needs serious preservation attention. The loss of the roof on the log barn, and the general poor condition of the roofs of the outbuildings are major concerns.

Between the Fitzpatrick Ranch and Helmville is the Barger Ranch, also from the late 19th century judging from the more polished example of Queen Anne style in the ranch house. It is living proof that not all of the Nevada Creek ranches have passed away. The Nevada Creek Water Users Association at Helmville still operates to distribute the invaluable water from the reservoir.

Between the Fitzpatrick Ranch and Helmville is the Barger Ranch, also from the late 19th century judging from the more polished example of Queen Anne style in the ranch house. It is living proof that not all of the Nevada Creek ranches have passed away. The Nevada Creek Water Users Association at Helmville still operates to distribute the invaluable water from the reservoir.  Helmville was another topic in my 1986 book. Throughout the Nevada Creek drainage, you could help but be impressed with the log construction, and the various types of notching used for the buildings. Helmville had a particular interesting grouping of wood frame and log buildings, which were highlighted by a 1984 photograph in the book. That exact view could not be replicated 30 years later but several of the old buildings still stood.

Helmville was another topic in my 1986 book. Throughout the Nevada Creek drainage, you could help but be impressed with the log construction, and the various types of notching used for the buildings. Helmville had a particular interesting grouping of wood frame and log buildings, which were highlighted by a 1984 photograph in the book. That exact view could not be replicated 30 years later but several of the old buildings still stood.

Helmville has a good bit of continuity. Along with the row of buildings on Montana 271 there is a turn of the 20th century gable-front cottage and a two-story lodge building that has been turned into a garage.

Helmville has a good bit of continuity. Along with the row of buildings on Montana 271 there is a turn of the 20th century gable-front cottage and a two-story lodge building that has been turned into a garage.

Trixie’s was the same fun dive that I always recalled, but the village’s historic buildings had been restored, looking good. Business appeared to be brisk. A new community church has been opened, and a major interpretive place for the “Lewis Minus Clark” expedition had been installed. Kudos to both the U.S. Forest Service and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail for allowing a bit of humor in this marker.

Trixie’s was the same fun dive that I always recalled, but the village’s historic buildings had been restored, looking good. Business appeared to be brisk. A new community church has been opened, and a major interpretive place for the “Lewis Minus Clark” expedition had been installed. Kudos to both the U.S. Forest Service and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail for allowing a bit of humor in this marker.

The school had also expanded from its New Deal core of the 1930s, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration. But the most noticeable change was the town’s street signs–first the fact that a small place had street signs but then the nostalgic backpacker theme of these cast iron marvels.

The school had also expanded from its New Deal core of the 1930s, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration. But the most noticeable change was the town’s street signs–first the fact that a small place had street signs but then the nostalgic backpacker theme of these cast iron marvels. Ovando is a good location on the Blackfoot River for sportsmen, anglers, and hikers headed into the Bob Marshall Wilderness–its recent change demonstrates the influence on those groups on the 21st century Montana landscape.

Ovando is a good location on the Blackfoot River for sportsmen, anglers, and hikers headed into the Bob Marshall Wilderness–its recent change demonstrates the influence on those groups on the 21st century Montana landscape.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters. The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory.

The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory. The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century.

The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century. Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history. Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses.

Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses. In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

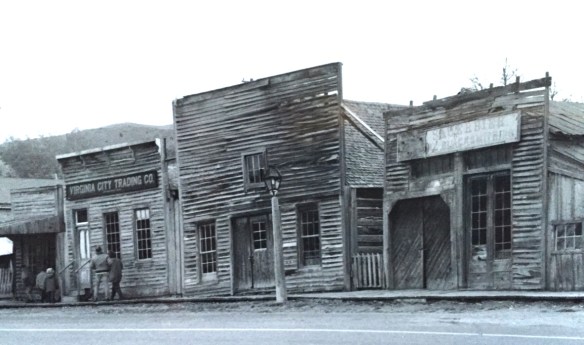

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

for places to rest, relax, and enjoy the precious hours away from the workplace. So much has changed in Anaconda since the closing of the smelter in the early 1980s–but the town’s distinctive places for recreation and relaxation remain, a big part of the reason Anaconda is one of my favorite places in Montana.

for places to rest, relax, and enjoy the precious hours away from the workplace. So much has changed in Anaconda since the closing of the smelter in the early 1980s–but the town’s distinctive places for recreation and relaxation remain, a big part of the reason Anaconda is one of my favorite places in Montana. Let’s start with the magnificent Art Deco marvel of the Washoe Theater. Designed in 1930 by B. Marcus Priteca but not finished and opened until 1936, the theater has stayed in operation ever since. It is remarkably intact, especially when owners refused to follow the multi-screen craze of the 1970s and kept the lobby and massive screen

Let’s start with the magnificent Art Deco marvel of the Washoe Theater. Designed in 1930 by B. Marcus Priteca but not finished and opened until 1936, the theater has stayed in operation ever since. It is remarkably intact, especially when owners refused to follow the multi-screen craze of the 1970s and kept the lobby and massive screen

A drink after the movie: still happens with regularity in Anaconda, due to the plethora of neighborhood bars, from the Anaconda Bar to the Thompson Bar. The range of sizes and styling speaks to the different experiences offered by these properties.

A drink after the movie: still happens with regularity in Anaconda, due to the plethora of neighborhood bars, from the Anaconda Bar to the Thompson Bar. The range of sizes and styling speaks to the different experiences offered by these properties.

The Elks Club in the heart of downtown is a totally different statement, with its sleek 1960s modernist facade over an earlier turn of the century Victorian styled brick building reflecting a more prosperous and larger membership.

The Elks Club in the heart of downtown is a totally different statement, with its sleek 1960s modernist facade over an earlier turn of the century Victorian styled brick building reflecting a more prosperous and larger membership.

With its glass block entrances and windows, the American Legion lodge seems like another lounge, but the American Eagle mural says otherwise.

With its glass block entrances and windows, the American Legion lodge seems like another lounge, but the American Eagle mural says otherwise.

If not bowling, why not read a book. At least that was the motivation behind Progressive reformers and their initiative to create “free” (meaning no membership fees) public libraries at the turn of the 20th century. Anaconda has one of the state’s earliest and most architecturally distinctive libraries in the Hearst Free Library.

If not bowling, why not read a book. At least that was the motivation behind Progressive reformers and their initiative to create “free” (meaning no membership fees) public libraries at the turn of the 20th century. Anaconda has one of the state’s earliest and most architecturally distinctive libraries in the Hearst Free Library.

Another Progressive-era institution is Washoe Park, established by the copper company and home to the first fish hatchery in the state. Washoe Park was a place for outdoor recreation, with ball fields, picnic areas, and amusement attractions. It also was home for the town’s baseball field and its historic grandstands and refreshment

Another Progressive-era institution is Washoe Park, established by the copper company and home to the first fish hatchery in the state. Washoe Park was a place for outdoor recreation, with ball fields, picnic areas, and amusement attractions. It also was home for the town’s baseball field and its historic grandstands and refreshment

New renovations at the park have been underway, improving trails, the hatchery, and the outdoor experience plus adding public interpretation at appropriate places. The park is being re-energized but respect still shown its early elements, such as the historic Alexander Glover cabin, built c. 1865 and identified as the oldest residence in Anaconda, which was moved into the park as an interpretive site, early, c. 1920.

New renovations at the park have been underway, improving trails, the hatchery, and the outdoor experience plus adding public interpretation at appropriate places. The park is being re-energized but respect still shown its early elements, such as the historic Alexander Glover cabin, built c. 1865 and identified as the oldest residence in Anaconda, which was moved into the park as an interpretive site, early, c. 1920. Another outdoor recreational space that has been receiving renovation is the historic Mitchell Stadium complex, a New Deal project of the Works Progress Administration from 1938-1939. The stadium, designed to give the high school modern facilities for football and track and field, is quite the place, retaining so much of its original understated Art Deco styling.

Another outdoor recreational space that has been receiving renovation is the historic Mitchell Stadium complex, a New Deal project of the Works Progress Administration from 1938-1939. The stadium, designed to give the high school modern facilities for football and track and field, is quite the place, retaining so much of its original understated Art Deco styling. Unlike Washoe Park, here was a new public space, in keeping with the New Dealers’ faith in recreation and community, that was not a creation of the copper company for adult workers but for high school athletes.

Unlike Washoe Park, here was a new public space, in keeping with the New Dealers’ faith in recreation and community, that was not a creation of the copper company for adult workers but for high school athletes.

But even on the links of this innovative adaptive reuse project you cannot escape the overwhelming presence of the copper company stack, and mounds of devastation it left behind. Here is an appropriate view that sums up the company influence on the distinctive place of Anaconda.

But even on the links of this innovative adaptive reuse project you cannot escape the overwhelming presence of the copper company stack, and mounds of devastation it left behind. Here is an appropriate view that sums up the company influence on the distinctive place of Anaconda. Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention.

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention. Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community. Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.