Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Wibaux ranch house, 1985.

When I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, a handful of ranches had been preserved as museums. On the eastern end of the state in Wibaux was the preserved ranch house of Pierre Wibaux, one of the 1880s cattle barons of eastern Montana and western North Dakota. The ranch house today remains as a historic site, and a state welcome center for interstate travelers–although you wish someone in charge would remove the rather silly awning from the gable end window.

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

not only preserves one of the earliest settlement landscapes in the state it also shows how successful ranches change over time. John Grant began the place before the Civil War: he was as much an Indian trader than ranch man. Grant Kohrs however looked at the rich land, the railroad line that ran through the place, and saw the potential for becoming a cattle baron in the late 19th century. To reflect his prestige and for his family’s comfort, the old ranch house was even updated with a stylish Victorian brick addition. The layers of history within this landscape are everywhere–not surprisingly. There is a mix of 19th and 20th century buildings here that you often find at any historic ranch.

When I was working with the Montana Historical Society in 1984-1985 there were two additional grand ranches that we thought could be added to the earlier preservation achievements. Both are now landmarks, important achievements of the last 30 years.

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

Here was one of the grand showplace ranches of the American West, with its own layers of a grand Queen Anne ranch house (still marked by the Shingle-style laundry house) of Daly’s time that was transformed into an even greater Classical Revival mansion by his Margaret Daly after her husband’s death. It is with us today largely due to the efforts of a determined local group, with support from local, state, and federal governments, a group of preservation non-profits, and the timely partnership of the University of Montana.

The second possibility was also of the grand scale but from more recent times–the Bair Ranch in Martinsdale, almost in the center of the state. Charles Bair had made his money in sheep and wise investments. His daughters traveled the world and brought treasures home to their Colonial Revival styled ranch house. To get a chance to visit with Alberta Bair here in the mid-1980s was a treat indeed.

Once again, local initiative preserved the ranch house and surrounding buildings and a local board operates both a house museum and a museum that highlights items from the family’s collections.

The success of the Bitter Root Stock Farm and the Bair Ranch was long in the making, and you hope that both can weather the many challenges faced by our public historic sites and museums today. We praise our past but far too often we don’t want to pay for it.

That is why family stewardship of the landscape is so important. Here are two examples from Beayerhead County. The Tash Ranch (above and below) is just outside of Dillon and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. But is also still a thriving family ranch.

The same is true for the Bremmer Ranch, on the way to Lemhi Pass. Here is a family still using the past to forge their future and their own stories of how to use the land and its resources to maintain a life and a culture.

One family ranch that I highlighted in my book, A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986), was the Simms-Garfield Ranch, located along the Musselshell River Valley in Golden Valley County, along U.S. Highway 12. This National Register-property was not, at

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

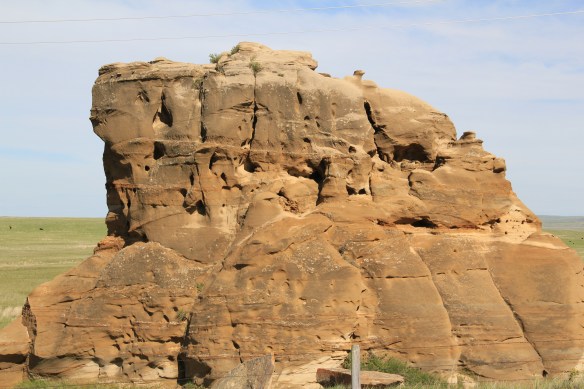

Similar traditions are expressed in another way at a more recent National Register-listed ranch, the Vogt-Nunberg Ranch south of Wibaux on Montana Highway 7. Actively farmed from 1911 to 1995, the property documents the changes large and small that happened in Montana agriculture throughout the 20th century.

The stories of these ranches are only a beginning. The Montana Preservation Alliance has done an admirable job of documenting the state’s historic barns, and the state historic preservation office has listed many other ranches to the National Register. But still the rural landscape of the Big Sky Country awaits more exploration and understanding.

Montana’s gateways into Yellowstone National Park are known far and wide. The most popular are associated with the trains that delivered mostly easterners to the wonderland of the park–West Yellowstone for the Union Pacific line and Gardiner for the Northern Pacific Railway.

Montana’s gateways into Yellowstone National Park are known far and wide. The most popular are associated with the trains that delivered mostly easterners to the wonderland of the park–West Yellowstone for the Union Pacific line and Gardiner for the Northern Pacific Railway. Cooke City, located in the corner of Park County, was never a railroad town but an overland connection that did not become popular until the development of the Beartooth Highway out of Red Lodge in the 1920s.

Cooke City, located in the corner of Park County, was never a railroad town but an overland connection that did not become popular until the development of the Beartooth Highway out of Red Lodge in the 1920s. It is all about the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) here–when it opens, Cooke City booms as a tourism oasis. When the highway closes for its long winter, business doesn’t end since the road to Mammoth Hot Springs far to the west is kept open as best as it can be, but the number of visitors drops remarkably. Snow mobile traffic in the winter has meant a lot to local business in the last 30 years.

It is all about the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) here–when it opens, Cooke City booms as a tourism oasis. When the highway closes for its long winter, business doesn’t end since the road to Mammoth Hot Springs far to the west is kept open as best as it can be, but the number of visitors drops remarkably. Snow mobile traffic in the winter has meant a lot to local business in the last 30 years.

Cooke City uses its mining past to define its identity today, from moving log mining shacks and cabins into town, as shown above, for potential new lures for tourism, to the recently established visitor center and museum, which includes some of the local mining

Cooke City uses its mining past to define its identity today, from moving log mining shacks and cabins into town, as shown above, for potential new lures for tourism, to the recently established visitor center and museum, which includes some of the local mining

Perhaps the best example is the rustic yet modern styling of the Mt Republic Chapel of Peace between Silver Gate and Cooke City on U.S. 212. It is no match for the soaring mountains that surround it but its quiet dignity reflects well the people and environment of this part of Montana.

Perhaps the best example is the rustic yet modern styling of the Mt Republic Chapel of Peace between Silver Gate and Cooke City on U.S. 212. It is no match for the soaring mountains that surround it but its quiet dignity reflects well the people and environment of this part of Montana.

The same can be said for Hoosier’s Bar–a favorite haunt here in Cooke City for several decades, easy to find with its neon sign, and then there is the throwback telephone booth–a good idea since many cell phones search for coverage in this area. Cooke City and Silver Gate are the smallest Montana gateways into Yellowstone National Park but they tell and preserve their story well.

The same can be said for Hoosier’s Bar–a favorite haunt here in Cooke City for several decades, easy to find with its neon sign, and then there is the throwback telephone booth–a good idea since many cell phones search for coverage in this area. Cooke City and Silver Gate are the smallest Montana gateways into Yellowstone National Park but they tell and preserve their story well. Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire. The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects.

The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects. The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena.

The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena. Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.

Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.  The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings.

The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings. While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959.

While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959. It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day.

It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day. Somehow it is most appropriate that my 300th post for Revisiting the Montana Landscape would find me back at Glacier National Park, especially the west side or Flathead County part of the park. From the first visit in 1982, Glacier always intrigued me–at first because of the tie between park creation and railroad development, then the Arts and Crafts/Chalet architecture associated with the park, and then high mountain Alpine environment. In the years since, I have eagerly grabbed a chance to get a cabin by Lake McDonald and just re-charge for a few days.

Somehow it is most appropriate that my 300th post for Revisiting the Montana Landscape would find me back at Glacier National Park, especially the west side or Flathead County part of the park. From the first visit in 1982, Glacier always intrigued me–at first because of the tie between park creation and railroad development, then the Arts and Crafts/Chalet architecture associated with the park, and then high mountain Alpine environment. In the years since, I have eagerly grabbed a chance to get a cabin by Lake McDonald and just re-charge for a few days. For the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work, however, I did not visit the west side of the park–the bulk of the travel took place between mid-February to mid-May 1984, meaning only the lower elevations such as Apgar Village were accessible. But already the state historic preservation office was aware that a major effort was underway to identify and nominate key properties within the park to the National Register of Historic Places, and by the end of the decade that process was largely complete. The National Park Service identified a range of historic resources from the turn of the 20th century to the Mission 66 program of the National Park Service during the 1960s–Glacier became one of the best studied historic landscapes in all of Montana.

For the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work, however, I did not visit the west side of the park–the bulk of the travel took place between mid-February to mid-May 1984, meaning only the lower elevations such as Apgar Village were accessible. But already the state historic preservation office was aware that a major effort was underway to identify and nominate key properties within the park to the National Register of Historic Places, and by the end of the decade that process was largely complete. The National Park Service identified a range of historic resources from the turn of the 20th century to the Mission 66 program of the National Park Service during the 1960s–Glacier became one of the best studied historic landscapes in all of Montana.

Register as an excellent example of Mission 66-associated architecture within the park. Burt L. Gewalt of the Kalispell firm Brinkman and Lenon was the architect.

Register as an excellent example of Mission 66-associated architecture within the park. Burt L. Gewalt of the Kalispell firm Brinkman and Lenon was the architect. Great Northern officials considered the lodge to be the center of the mountain experience on the park’s west side. From there visitors could take overnight hikes to two other facilities, shown below, the Granite Park Chalet to the northeast or the Sperry Chalet to the southeast of Lake McDonald, both of which are also listed in the National Register.

Great Northern officials considered the lodge to be the center of the mountain experience on the park’s west side. From there visitors could take overnight hikes to two other facilities, shown below, the Granite Park Chalet to the northeast or the Sperry Chalet to the southeast of Lake McDonald, both of which are also listed in the National Register.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

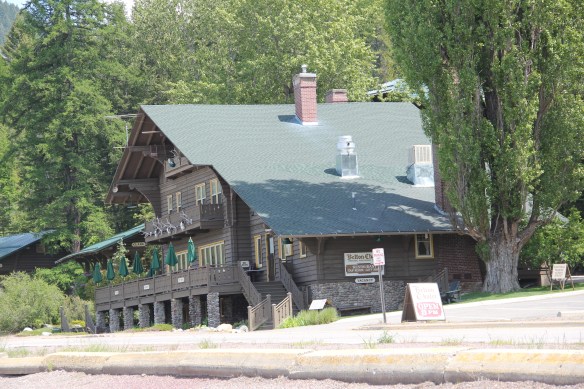

The answer was yes, to both questions. Here is an early 20th century log building landmark on a highway where the traffic seems to never end. It is also along the corridor of a new recreational system–the Great Northern Rails to Trails linear park that uses an old railroad corridor to connect the city to the country in Flathead County.

The answer was yes, to both questions. Here is an early 20th century log building landmark on a highway where the traffic seems to never end. It is also along the corridor of a new recreational system–the Great Northern Rails to Trails linear park that uses an old railroad corridor to connect the city to the country in Flathead County.

The trail allows bikers to see the rural landscape, still dotted with family farms, of the Smith Valley as it stretches west to Kila, where the old Cottage Inn has been converted in the last few years into the Kila Pub, complete with the Arts and Crafts/Tudor theme associated with the railroad corridor.

The trail allows bikers to see the rural landscape, still dotted with family farms, of the Smith Valley as it stretches west to Kila, where the old Cottage Inn has been converted in the last few years into the Kila Pub, complete with the Arts and Crafts/Tudor theme associated with the railroad corridor.

To the north of Kalispell and Whitefish U.S. Highway 93 takes you past the ski developments into a thick forested area, managed in part as the Stillwater State Forest.

To the north of Kalispell and Whitefish U.S. Highway 93 takes you past the ski developments into a thick forested area, managed in part as the Stillwater State Forest.

from the 1920s into the 1960s. While several are from the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s, state ranger Pete De Groat built his log residence in 1928 in the Rustic Style. Stillwater was Montana’s first state forest.

from the 1920s into the 1960s. While several are from the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s, state ranger Pete De Groat built his log residence in 1928 in the Rustic Style. Stillwater was Montana’s first state forest.

The images above and those below come from those well maintained neighborhoods, where the sense of place and pride is so strongly stated.

The images above and those below come from those well maintained neighborhoods, where the sense of place and pride is so strongly stated.

Kalispell’s Main Street–the stem of the T-plan that dates to the town’s very beginning as a stop on the Great Northern Railway–has a different mix of businesses today than 30 years ago when I visited during my state historic preservation plan survey. It also now is a historic district within National Register of Historic Places, noted for its mix of one-story and two-story Western Commercial style businesses along with large historic hotels and an opera house for entertainment.

Kalispell’s Main Street–the stem of the T-plan that dates to the town’s very beginning as a stop on the Great Northern Railway–has a different mix of businesses today than 30 years ago when I visited during my state historic preservation plan survey. It also now is a historic district within National Register of Historic Places, noted for its mix of one-story and two-story Western Commercial style businesses along with large historic hotels and an opera house for entertainment. The Opera House, and I’m sorry you have to love the horse and buggy sign added to the front some years ago, dates to 1896 as the dream of merchant John MacIntosh to give the fledging community everything it needed. On the first floor was his store, which over the years sold all sorts of items, from thimbles to Studebakers. The second floor was a community space, for meetings, a gymnasium, and even from a brief period from 1905 to 1906 a skating rink. In this way, MacIntosh followed the ten-year-old model of a much larger building in a much larger city, the famous Auditorium Building in Chicago, providing Kalispell with a major indoor recreation space and landmark. Allegedly over 1000 people attended a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon after the opening.

The Opera House, and I’m sorry you have to love the horse and buggy sign added to the front some years ago, dates to 1896 as the dream of merchant John MacIntosh to give the fledging community everything it needed. On the first floor was his store, which over the years sold all sorts of items, from thimbles to Studebakers. The second floor was a community space, for meetings, a gymnasium, and even from a brief period from 1905 to 1906 a skating rink. In this way, MacIntosh followed the ten-year-old model of a much larger building in a much larger city, the famous Auditorium Building in Chicago, providing Kalispell with a major indoor recreation space and landmark. Allegedly over 1000 people attended a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon after the opening.

The Alpine Lighting Center dates to 1929 when local architect Fred Brinkman designed the store for Montgomery Ward, the famous Chicago-based catalog merchant. Its eye-catching facade distinguished it from many of the other more unadorned two-part commercial blocks on Main Street.

The Alpine Lighting Center dates to 1929 when local architect Fred Brinkman designed the store for Montgomery Ward, the famous Chicago-based catalog merchant. Its eye-catching facade distinguished it from many of the other more unadorned two-part commercial blocks on Main Street.