When I lived in Helena from 1981 to 1985 one of my favorite jaunts was along U.S. Highway 12 from Townsend to Roundup. It remains so today, 40 years later. My initial interest centered on railroad corridors. Helena to Townsend followed the Northern Pacific Railroad and a good bit of the Missouri River (now Canyon Ferry Lake).

It was a brilliant day with fall colors just popping as we left US 287 and turned into the heart of Townsend.

As soon as you leave town to the east you encounter a lovely mix of ranches and irrigated fields until you thread your way through a national forest along Deep Creek.

We decided to continue east by briefly jumping off US 12 and go to Montana 284 so we could follow the Milwaukee Road corridor from Lennep to Martinsdale where we would reconnect with US 12. Two of my travelers had never been to the Milwaukee Road “ghost town” of Lennep. It was a beautiful morning to be there.

You first realize that this abandoned railroad corridor is different when you encounter an electric powerhouse—the Milwaukee Road’s tracks were electrified from Harlowton Montana west to Idaho.

At Lennep the landmarks remain—the Trinity Lutheran Church, the store, the school, a teacher’s cottage and an early notched log house—but all were a little worse for the wear compared to my last visit 10 years earlier.

As we traveled east that morning we quickly moved through the county seats of Harlowton and Ryegate to get to Roundup by lunch. The Musselshell Valley was brilliant even as signs of the old railroad almost disappeared.

Roundup continues its renaissance with new businesses and restored buildings. The town core, clustered around the intersection of US highways 12 and 87, was busy on a fall weekend.

As I observed a few years ago Roundup residents worked together and created a plan—and the place continues to work the plan, from the adaptive reuse of its historic stone school to the careful stewardship of its historic fairgrounds. It’s impressive.

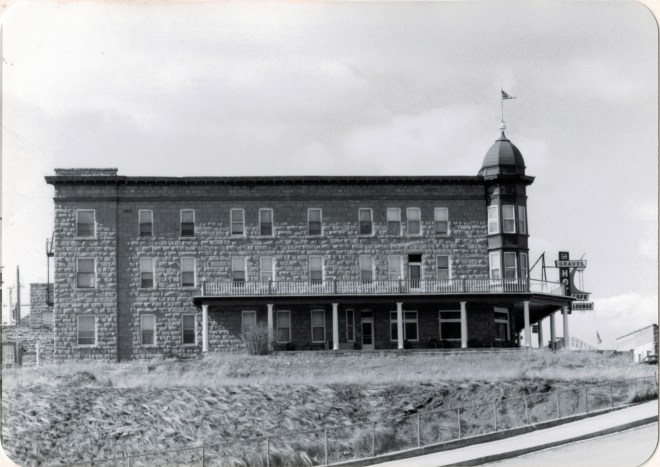

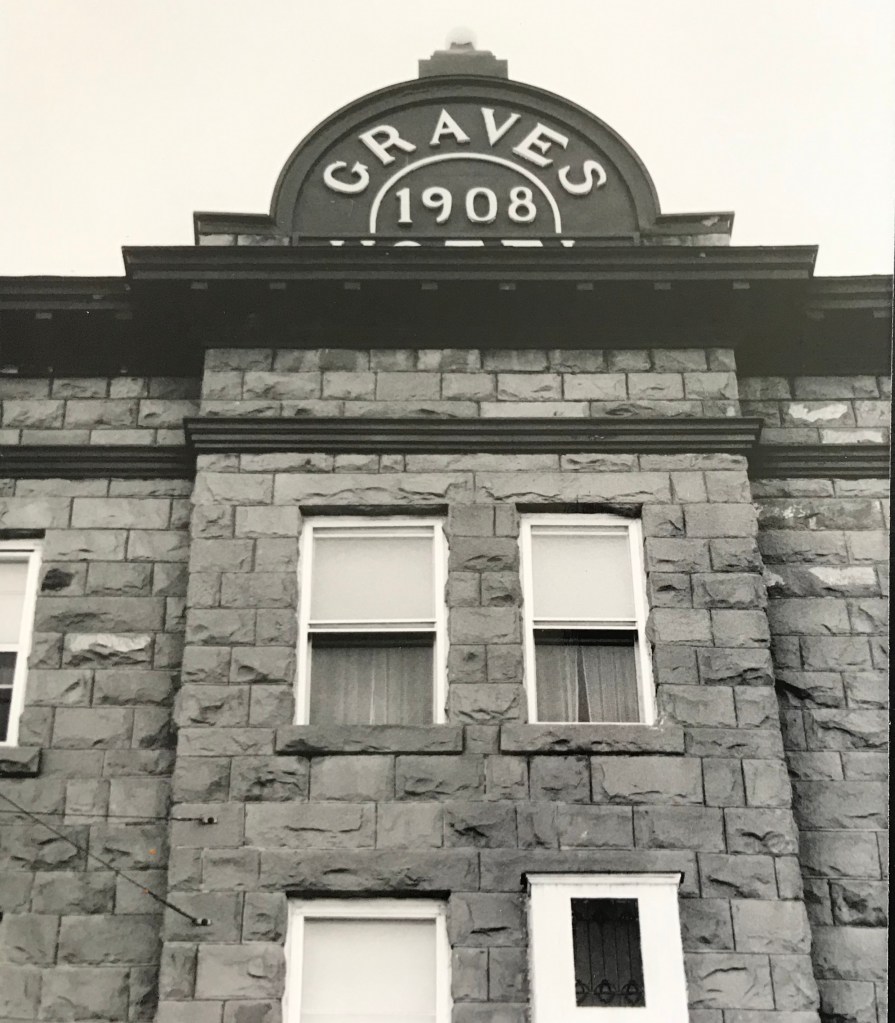

After Roundup we stopped at two county seats on the return to Helena. Harlowton was rocked by the closing of the Milwaukee Road over 40 years ago. It has struggled to reach the economic comeback achieved at Roundup. But the historic stone buildings have great potential. Three of them are now part of a large museum complex.

Then there’s the newcomer: the Gally’s microbrewery and pub, housed in the 1913 Montana Block.

It’s a great place for local beer and good conversation—and maybe the start of something good for the town.

US Highway 12 was torn up for major repairs when I last visited White Sulphur Springs last decade. The improvement along its population growth and the ever expanding hot springs gives the place a new look, reflected in new catchy fronts to local bars along with new businesses such as a huge Town Pump.

But historic White Sulphur Springs is doing ok too: the New Deal constructed Meagher County Courthouse is still a roadside landmark while the old railroad corridor, just west of the Hot Springs, remains, awaiting its rebirth.

These places are mere highlights along a historic route that’s worth a drive anytime in the fall.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country. I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century. Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered. The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

entertained generations of Grizzly students and fans–note the window mural. But it is just one of several favorite Stockman’s Bars I have encountered in my Montana fieldwork. My top choice is actually on the other end of the state–almost in North Dakota in fact–the Stockman’s Bar in Wibaux.

entertained generations of Grizzly students and fans–note the window mural. But it is just one of several favorite Stockman’s Bars I have encountered in my Montana fieldwork. My top choice is actually on the other end of the state–almost in North Dakota in fact–the Stockman’s Bar in Wibaux.

The woman’s club began c. 1921 and had already made a major contribution to the town’s well-being in establishing its first library. After World War II, however, club members felt they should once again help build the community, by building a youth center and veterans memorial garden. Mrs. Norman Good proposed the project in 1946 and Mrs. G. D. Martin provided the first substantial donation. The club then held fundraisers of all sorts. By 1950, construction was underway, with contractor Clyde Wilson building the center with logs from Colby and Sons in Kila, Montana.

The woman’s club began c. 1921 and had already made a major contribution to the town’s well-being in establishing its first library. After World War II, however, club members felt they should once again help build the community, by building a youth center and veterans memorial garden. Mrs. Norman Good proposed the project in 1946 and Mrs. G. D. Martin provided the first substantial donation. The club then held fundraisers of all sorts. By 1950, construction was underway, with contractor Clyde Wilson building the center with logs from Colby and Sons in Kila, Montana. As the youth center was under construction, the woman’s club also reached an agreement with the school board to use land for the construction of a new football field, named McQuitty Field. Located behind the youth center, the field opened in 1950.

As the youth center was under construction, the woman’s club also reached an agreement with the school board to use land for the construction of a new football field, named McQuitty Field. Located behind the youth center, the field opened in 1950.

Thus, on U.S. Highway 12 lies the public recreation heart of Harlowton–a postwar gift of residents and service clubs to the community. In 1956, the woman’s club deeded the Youth Center to the Kiwanis Club, which still manages it today.

Thus, on U.S. Highway 12 lies the public recreation heart of Harlowton–a postwar gift of residents and service clubs to the community. In 1956, the woman’s club deeded the Youth Center to the Kiwanis Club, which still manages it today.

Road, it once also had several hotels and more short-term housing for workers and travelers–a good bit of that has disappeared, or is disappearing.

Road, it once also had several hotels and more short-term housing for workers and travelers–a good bit of that has disappeared, or is disappearing.

It is difficult to visit Harlowton and not notice the mammoth Montana Flour Mills set of concrete grain silos–today’s silent sentinels of what ranchers once produced in abundance in these lands.

It is difficult to visit Harlowton and not notice the mammoth Montana Flour Mills set of concrete grain silos–today’s silent sentinels of what ranchers once produced in abundance in these lands. The mill, made from locally quarried stone, came within months of the completion of the railroad to Harlowton–the concrete silos reflected the hopes of investors and local ranchers, as grain production soared in the 1910s–reaching some 1.2 million bushels in 1918. It wasn’t called Wheatland County for nothing. I still wish the big electric sign that once adorned the silos was still there.

The mill, made from locally quarried stone, came within months of the completion of the railroad to Harlowton–the concrete silos reflected the hopes of investors and local ranchers, as grain production soared in the 1910s–reaching some 1.2 million bushels in 1918. It wasn’t called Wheatland County for nothing. I still wish the big electric sign that once adorned the silos was still there.