Sad news came out of the state capitol last week when budget cuts gave the Montana Historical Society no choice but to announce that its uber talented staff just don’t have the funding to travel to the hundreds of important places across the state, to gather stories, preserve historic buildings, conserve invaluable documents and photographs, and to celebrate with communities both large and small the history, traditions, and people that made Montana the special place it is.

It’s unfortunate when a state steps back from its past and thinks its future is better without it. When I look for those who built the state, the deep past is where I start, and the leaps forward in how Montana’s tribes are documenting and interpreting their history to their terms and needs, one of the most important developments in Montana’s heritage development over the last 30 plus years.

Then there are the properties that link the peoples of Montana and their sense of themselves and their past–cemeteries large and small across the state, where veterans are commemorated and families celebrated.

Fort Kipp Cemetery, above, is one of those place, nestled on the river bluffs overlooking the Missouri River. On a larger scale but still intimate, personal, and compelling is the city cemetery of Red Lodge, hundreds of miles away. Here surrounded by the mountains

Fort Kipp Cemetery, above, is one of those place, nestled on the river bluffs overlooking the Missouri River. On a larger scale but still intimate, personal, and compelling is the city cemetery of Red Lodge, hundreds of miles away. Here surrounded by the mountains

are graves from the early Finnish residents who came to work at the coal mines and build a community. Some are of a traditional design, immediately translated from the old country. Others–like the cast iron family marker shown above–are as mainstream as American industry could make it at the turn of the twentieth century: a prefabricated marker cast somewhere back east but with Finnish lettering, speaking to those who also came over in c.1900 to build a new land.

The Finnish imprint on the landscape of Carbon County has been eclipsed by generations of growth since the early 1900s, but as the 2016 Road Show of the Montana Preservation Alliance demonstrated, buildings large and small are still part of the landscape. With a few acres of land outside of Red Lodge, Finnish settlers and their descendants have maintained a place of community–the Kavela–which remains vibrant some 100 years later. At this place of ethnic identity and celebration, you almost feel like an intruder–that you have stepped inside a sacred circle as an outsider. But families go out of their way to make you feel welcome, through fellowship, good food, and stories of past and present. The Kavela naturally features one of the most traditional Finnish community buildings–the sauna, built of concrete in the 1920s. Speak of tradition, ethnic pride, and assimilation–a concrete sauna might say it all.

Indeed what you can find in the Finnish landscape of Carbon County is repeated countless times across Big Sky Country, just in different languages and with different forms. It is why you get off the interstates and travel the backroads, the dirt roads, for

the markers of the nations that built our nation can be almost anywhere. It might be of the many ethnicities who mined the copper of Butte, or the African American railroad

workers and other average citizens who established permanent institutions such as the Bethel Union AME Church in Great Falls, pictured below.

Stonemasons from Croatia are credited with many of the architecturally striking stone buildings in Lewistown, shown below, whereas if you stop and explore the state capital

of Helena, you can see where Irish Americans banded together to fund some of the state’s most iconic structures, from the majestic Catholic Cathedral that overlooks the city and the commanding statue of General Thomas Meagher in front of the State Capitol.

From the Meagher statue it is only a few steps to the east to the doors of the Montana Historical Society. Its operating hours are fewer but you will find an institution not just of the past but of the future for like the land itself, the society, its collections, and dedicated staff are the keepers of the things and words that remain from those who built the state. The idea that Montana can stride into the 21st century without the Montana Historical Society is folly, defined.

The Main Drive-In in Conrad is located on the historic federal hi way (U.S. 91) and still draws in customers despite competition from chains and the diversion of most traffic to Interstate Highway I-15.

The Main Drive-In in Conrad is located on the historic federal hi way (U.S. 91) and still draws in customers despite competition from chains and the diversion of most traffic to Interstate Highway I-15. At Scobey, Shu Mei’s Kitchen converted an earlier drive-in into a family restaurant on Montana Highway 13 in northeast Montana.

At Scobey, Shu Mei’s Kitchen converted an earlier drive-in into a family restaurant on Montana Highway 13 in northeast Montana.

It’s not surprising that Lewistown, in the middle of the state faraway from the interstate system, has several still operating roadside establishments from the mid-20th century, such as the Wagon Wheel Drive-In (above–and being a southerner I loved the sign that bragged “we have MT Dew”) and the Dash Inn (below), which opened in 1952.

It’s not surprising that Lewistown, in the middle of the state faraway from the interstate system, has several still operating roadside establishments from the mid-20th century, such as the Wagon Wheel Drive-In (above–and being a southerner I loved the sign that bragged “we have MT Dew”) and the Dash Inn (below), which opened in 1952.

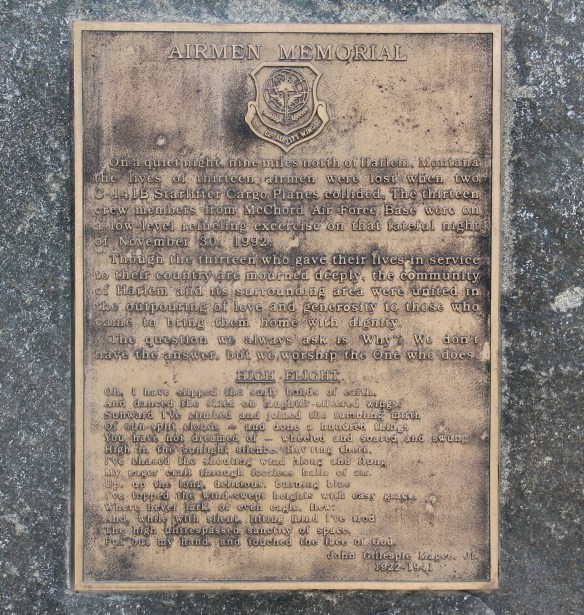

On this Memorial Day 2017 it is appropriate to celebrate the many memorials created by Montanans to recognize and commemorate the citizen soldiers who have served the armed forces of the United States. I am not adding much commentary because the memorials, both large and small, speak powerfully for themselves, and reflect the best of our values as a nation.

On this Memorial Day 2017 it is appropriate to celebrate the many memorials created by Montanans to recognize and commemorate the citizen soldiers who have served the armed forces of the United States. I am not adding much commentary because the memorials, both large and small, speak powerfully for themselves, and reflect the best of our values as a nation.

Another compelling new memorial, at least it was installed after my historic preservation plan survey of 1984-1985, are these granite slabs, framed by the mountains, at Arlee.

Another compelling new memorial, at least it was installed after my historic preservation plan survey of 1984-1985, are these granite slabs, framed by the mountains, at Arlee.

Dillon had significantly expanded its earlier veterans memorial (on the left) along the federal highway into an impressive new city park, the Southwest Montana Veterans Memorial.

Dillon had significantly expanded its earlier veterans memorial (on the left) along the federal highway into an impressive new city park, the Southwest Montana Veterans Memorial. Even with the many changes in Ennis, the town has maintained its Veterans Memorial Park as a beautiful public park.

Even with the many changes in Ennis, the town has maintained its Veterans Memorial Park as a beautiful public park.

Hamilton’s veterans memorial along U.S. Highway 93 will be a landmark for generations.

Hamilton’s veterans memorial along U.S. Highway 93 will be a landmark for generations.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country.

In the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, the impact of lodging chains in Montana was pretty limited to the larger towns, and gateways to the national parks. Many what I called “mom and pop” motels, largely from the pre-interstate highway era of the 1940s and 1950s, still operated. I was working with the state employee lodging rate of $24 a night (remember it was 1984!) and I found that the per diem eliminated the chains and I was left with the local establishments. During those months of intense travel I came to respect and really like the Moms and Pops. Several of the places I stayed in 1984-1985 are long gone–but ones like the Lazy J Motel in Big Timber remain. In this post I am merely sharing a range of historic motels from across Big Sky Country. I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

I began the fieldwork in February 1984 and the first stop was a public meeting at the Toole County Courthouse in Shelby. My first overnight was just as memorable–for good reasons–at the O’Haire Manor Motel. Its huge neon sign on the town’s main street, which was U.S. Highway 2, could not be missed, and actually the sign replaced a building that once stood along the commercial district, knocking it down so travelers would have a clear shot to the motel itself.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Cut Bank’s Glacier Gateway, on the other hand, reminded visitors that it was that “coldest place” in the United States that they had heard about in weather forecasts.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century.

Another example from the old Yellowstone Trail and U.S. Highway 10 is the Shade Tree Inn Motel in Forsyth–although coal and railroad workers help somewhat to keep it going in the 21st century. Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Just a block west of another historic section of U.S. Highway 10 in Deer Lodge is the Downtowner Motel, with its sloping roof and extended rafters representing the best in “contemporary” style from the 1960s. This place too was clean, cheap, and well located for a day of walking the town back in 1984.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

Not only have the changes in traffic patterns been important, the present generation’s preference for chain motels–and the proliferation of chains across the state–have shaped the future of the mid-20th century motel. A good example is the challenges facing the continuation of the Cherry Hill Motel in Polson, located along U.S. Highway 93. Here was a favorite spot in 1984–near a killer drive-in–a bit out of the noise of the town, and sorta fun surroundings with a great view of Flathead Lake.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered.

The place was up for sale in 2015–and the internet today tells me that it is “permanently closed.” I hope it can find a new owner and is still there when I next return to Polson but with the general boom in the Flathead Lake region, one assumes its days are numbered. The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

The bear might be hugging the tree but does anyone else care enough–or want this type of lodging, complete with the “picture window” of the 1950s and 1960s, in the comfort obsessed 21st century?

Paul E. Davis’ gravemarker at Valley Cemetery, along the historic Mullan Road, in Powell County is an early example of the WWI doughboy bronzed and rooted in Montana soil. The plaque says “America Over the Top,” a reference to the courage it took to jump out of the trenches and charge the enemy but also a reference to how the world war literally put America in a new position of world leadership.

Paul E. Davis’ gravemarker at Valley Cemetery, along the historic Mullan Road, in Powell County is an early example of the WWI doughboy bronzed and rooted in Montana soil. The plaque says “America Over the Top,” a reference to the courage it took to jump out of the trenches and charge the enemy but also a reference to how the world war literally put America in a new position of world leadership.

Community Center Bowl in Hardin, Big Horn County, is a wonderful recreational space, with its bays defined by c. 1960 styled “picture windows” framed in glass blocks. The owners have refurbished the lanes two years ago–this institution still has years left in it.

Community Center Bowl in Hardin, Big Horn County, is a wonderful recreational space, with its bays defined by c. 1960 styled “picture windows” framed in glass blocks. The owners have refurbished the lanes two years ago–this institution still has years left in it.

From the southeast corner of the state to its northwest corner–the Trojan Lanes (so named for the school mascot) in Troy, Montana. Here you find the type of alley that is common throughout the small towns of Big Sky Country. Not only do you have a recreational center but you often have the best family restaurant in town. That’s the

From the southeast corner of the state to its northwest corner–the Trojan Lanes (so named for the school mascot) in Troy, Montana. Here you find the type of alley that is common throughout the small towns of Big Sky Country. Not only do you have a recreational center but you often have the best family restaurant in town. That’s the case where at Troy’s Trojan as well as–returning to the southeast corner–the Powder River Lanes in Broadus. This tiny county seat has lost several of its classic cafes from the 1980s–the Montana Bar and Cafe on the opposite side of the town square being my favorite in 1984–but Powder River Lanes makes up for it.

case where at Troy’s Trojan as well as–returning to the southeast corner–the Powder River Lanes in Broadus. This tiny county seat has lost several of its classic cafes from the 1980s–the Montana Bar and Cafe on the opposite side of the town square being my favorite in 1984–but Powder River Lanes makes up for it. I am sorta partial to the small-town lanes, like the Lucky Strike above in Ronan, Lake County. Located next door to “Entertainer Theatre,” this corner of the town is clearly its center for pop culture experience.

I am sorta partial to the small-town lanes, like the Lucky Strike above in Ronan, Lake County. Located next door to “Entertainer Theatre,” this corner of the town is clearly its center for pop culture experience. Another fav–admittedly in a beat-up turn of the 20th century building–is Roper Lanes and Lounge in Whitehall, Jefferson county, in the southwest corner of the state. Gotta love the painted sign over the entrance–emojis before they were called emojis.

Another fav–admittedly in a beat-up turn of the 20th century building–is Roper Lanes and Lounge in Whitehall, Jefferson county, in the southwest corner of the state. Gotta love the painted sign over the entrance–emojis before they were called emojis.

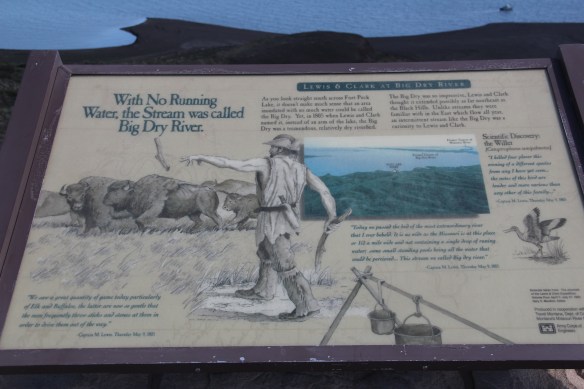

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now. New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do.

New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do. You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

St. Joseph Catholic Church, perched now on a barren bluff facing the lake, was moved about 2.5 miles east to its present location in 1954. Originally near the river in what was then known as the Canton Valley settlement, the church building is one of the state’s oldest, dating to 1874-1875 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The proud Gothic styled church is the remnant of one of the valley’s earliest settlements.

St. Joseph Catholic Church, perched now on a barren bluff facing the lake, was moved about 2.5 miles east to its present location in 1954. Originally near the river in what was then known as the Canton Valley settlement, the church building is one of the state’s oldest, dating to 1874-1875 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The proud Gothic styled church is the remnant of one of the valley’s earliest settlements.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950. Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural

Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City.

statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City. Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive.

at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive. Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor

Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.