Monida, at the Idaho-Montana border, on Interstate I-15.

Country towns of Beaverhead County–wait, you cry out: isn’t every town in Beaverhead County a country town? Well yes, since Dillon, the county seat, has a single stop light, you can say that. But Dillon is very much an urban oasis compared to the county’s tiny villages and towns scattered all about Beaverhead’s 5,572 square miles, making it the largest county in Montana.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

The next town north on the corridor created by the railroad/highway/interstate is Lima,  which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

Lima is a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, the plan favored by the engineers of the Utah and Northern as the railroad moved into Montana. The west side of the tracks, where the two-lane U.S. Highway 91 passed, was the primary commercial district, with several brick and frame two-story buildings ranging from the 1880s to the 1910s.

The east side, opposite old U.S. Highway 91, was a secondary area; the Lima Historical Society is trying to keep an old 1880s building intact for the 21st century.

The town’s comparative vitality is shown by its metal Butler Building-like municipal building, and historic churches, ranging from a early 20th century shingle style to a 1960s contemporary style Gothic church of the Latter Day Saints.

The town’s pride naturally is its school, which developed from the early 20th century two-story brick schoolhouse to become the town’s center of community.

Eight miles to the north is a very different historic schoolhouse, the one-story brick Dell school (1903), which had been converted into a wonderful cafe when I stopped in 1984. It is still a great place–if you don’t stop here for pie or a caramel roll (or both), you goofed.

The Calf-A is not the only place worth a look at Dell, a tiny railroad town along the historic Utah and Northern line, with the Tendroy Mountains in the background. Dell still has its

post office, within its one store, its community hall, and a good steakhouse dive, the false-front Stockyard Inn. But most importantly, for an understanding of the impact of World

War II on Montana, Dell has an air-strip, which still contains its 1940s B-17 Radar base, complete with storehouse–marked by the orange band around the building–and radar tower. Kate Hampton of the Montana State Historic Preservation Office in 2012 told me to be of the lookout for these properties. Once found throughout Montana, and part of the guidance system sending planes northward, many have disappeared over the years. Let’s hope the installation at Dell remains for sometime to come.

There are no more towns between Dell and Dillon but about halfway there is the Clark Canyon Reservoir, part of the reshaping of the northwest landscape by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in the 1960s. The bureau in 1961-1964 built the earthen dam and created the

reservoir, which inundated the small railroad town of Armstead, and led to the re-routing of U.S. Highway 91 (now incorporated into the interstate at this point).

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

effort to mark and interpret the site came from the Daughters of the American Revolution, who not surprisingly focused on the Sacajawea story. Reclamation officials added other markers after the construction of the dam and reservoir.

In this century the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail has added yet another layer of public interpretation in its attempt to tell the whole story of the expedition and its complicated relations with the Native Americans of the region.

North of Dillon along the old route of U.S. Highway 91 and overlooking the corridor of the Utah and Northern Railroad is another significant Lewis and Clark site, known as Clark’s Lookout, which was opened to the public during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial of the early 21st century.

The lookout is one of the exciting historic sites that have been established in Montana in the 30 years since my initial survey for the state historic preservation plan. Not only does the property interpret an important moment in the expedition’s history–from this vantage point William Clark tried to understand the countryside before him and the best direction to take–it also allows visitors to literally walk in his footsteps and imagine the same perspective.

Of course what Clark viewed, and what you might see, are vastly different–the tracks of the Utah and Northern, then route of old U.S. 91 are right up front, while the town of Dillon creeps northward toward the lookout.

Our last stop for part one of Beaverhead’s country towns is Glen, a village best accessed by old U. S. Highway 91. A tiny post office marks the old town. Not far away are two historic

North of Glen you cross the river along old U.S. Highway 91 and encounter a great steel tress bridge, a reminder of the nature of travel along the federal highways of the mid-20th century.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains. Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years.

Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years. The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution

The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies. I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer

I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

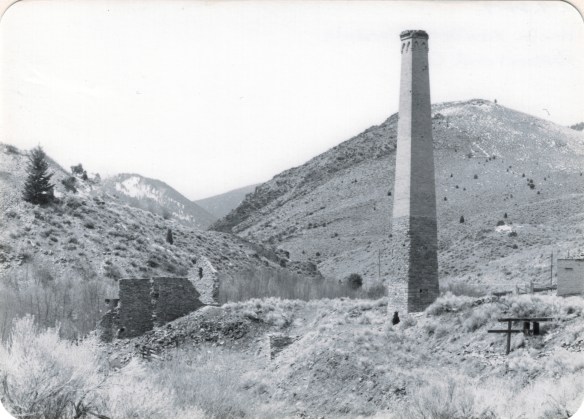

At Farlin, the scars of mining are everywhere, surrounded by sage grass, brush, and scattered trees, trying to recover in what was once a denuded landscape. Operations had ended by the time of the Great Depression. While never a huge place–population estimates top out at 500–Farlin is representative of the smaller mining operations that reshaped the rural western Montana landscape. Not every place became a Butte, or a Virginia City. Properties like Farlin help to tell us of the often lonely and exceedingly difficult search for opportunity in the Treasure State over 100 years ago.

At Farlin, the scars of mining are everywhere, surrounded by sage grass, brush, and scattered trees, trying to recover in what was once a denuded landscape. Operations had ended by the time of the Great Depression. While never a huge place–population estimates top out at 500–Farlin is representative of the smaller mining operations that reshaped the rural western Montana landscape. Not every place became a Butte, or a Virginia City. Properties like Farlin help to tell us of the often lonely and exceedingly difficult search for opportunity in the Treasure State over 100 years ago.

When I returned to Glendale in 2012, I made sure to take a replica shot of the place I had photographed almost 30 years earlier. But I also went father and did my best to document a mining landscape in danger of disappearing in the 21st century. Below is an image when the Hecla smelter was in full production.

When I returned to Glendale in 2012, I made sure to take a replica shot of the place I had photographed almost 30 years earlier. But I also went father and did my best to document a mining landscape in danger of disappearing in the 21st century. Below is an image when the Hecla smelter was in full production. There are some intact buildings at Glendale, but also numerous parts of buildings, facades and foundations that convey how busy the Glendale Road was some 100 years ago.

There are some intact buildings at Glendale, but also numerous parts of buildings, facades and foundations that convey how busy the Glendale Road was some 100 years ago.

Hecla Mining Company operated 28 kilns at a site a few miles away. Within the Beaverhead-Deer Lodge National Forest, the Canyon Creek Kilns are a remarkable property, preserved and now interpreted through the efforts of the U.S. Forest Service. The Forest Service should be commended for this effort. As the images below suggest, this property is one of the best places in Montana to stop and think of the mining landscape of the turn of the twentieth century and imagine what a moonscape it would have been 100 years ago when the kilns consumed all of the surrounding timber.

Hecla Mining Company operated 28 kilns at a site a few miles away. Within the Beaverhead-Deer Lodge National Forest, the Canyon Creek Kilns are a remarkable property, preserved and now interpreted through the efforts of the U.S. Forest Service. The Forest Service should be commended for this effort. As the images below suggest, this property is one of the best places in Montana to stop and think of the mining landscape of the turn of the twentieth century and imagine what a moonscape it would have been 100 years ago when the kilns consumed all of the surrounding timber.

The Big Hole Valley was a place of interest to me in 1984, noted by the image above, for how ranches used logs to build the physical infrastructure–the log snake fences, the gates, the log barns and other ranch structures–of their properties.

The Big Hole Valley was a place of interest to me in 1984, noted by the image above, for how ranches used logs to build the physical infrastructure–the log snake fences, the gates, the log barns and other ranch structures–of their properties.

What I didn’t give as much attention to, already commented on in this blog at numerous places, are the irrigation ditches, a more consistent supply of water that allowed ranchers to expand production.

What I didn’t give as much attention to, already commented on in this blog at numerous places, are the irrigation ditches, a more consistent supply of water that allowed ranchers to expand production.

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse.

building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse. Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop.

Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop. But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

Nestled where Montana Highway 287 encounters U.S. Highway 287 in the southern end of Madison County, Ennis has changed in significant ways in the last 30 years. Its earlier dependence on automobile tourism to Yellowstone National Park has shifted into the favor of population growth and development in this portion of the county.

Nestled where Montana Highway 287 encounters U.S. Highway 287 in the southern end of Madison County, Ennis has changed in significant ways in the last 30 years. Its earlier dependence on automobile tourism to Yellowstone National Park has shifted into the favor of population growth and development in this portion of the county. The iconic Ennis Cafe, always a favorite place back in the day of the statewide work, remains, with a new false front emphasizing the wildlife and open spaces of this area. That place, along with several classic watering holes, served not only locals but the

The iconic Ennis Cafe, always a favorite place back in the day of the statewide work, remains, with a new false front emphasizing the wildlife and open spaces of this area. That place, along with several classic watering holes, served not only locals but the

of a section of the highway where you will encounter magnificent views of the Madison River Valley and open ranch lands.

of a section of the highway where you will encounter magnificent views of the Madison River Valley and open ranch lands.

In restoring Virginia City, the Bovey family thus worked within a local government context. The Montana Heritage Foundation also works within that context today.

In restoring Virginia City, the Bovey family thus worked within a local government context. The Montana Heritage Foundation also works within that context today. There was no living community here to speak of. It presented the opportunity for the Boveys to acquire and save other buildings from the area, however. The Finney property became the historic foundation of one of the state’s first “building zoos”–a collection of historic buildings moved together to tell a local history story. In 1984, when I was surveying Montana for the state historic preservation plan process, I paid little to no attention to Nevada City–here, I thought, was fake western history, with a bunch of moved buildings, which by definition are rarely eligible for the National Register.

There was no living community here to speak of. It presented the opportunity for the Boveys to acquire and save other buildings from the area, however. The Finney property became the historic foundation of one of the state’s first “building zoos”–a collection of historic buildings moved together to tell a local history story. In 1984, when I was surveying Montana for the state historic preservation plan process, I paid little to no attention to Nevada City–here, I thought, was fake western history, with a bunch of moved buildings, which by definition are rarely eligible for the National Register.

Nevada City tells multiple stories. One of the most apparent is how heritage tourism has shaped the late 20th century historic preservation movement. The lodging and restaurant at Nevada City is part of the general sustainability plan for the entire operation. The authentic environment and ease of highway access are major draws for tourists.

Nevada City tells multiple stories. One of the most apparent is how heritage tourism has shaped the late 20th century historic preservation movement. The lodging and restaurant at Nevada City is part of the general sustainability plan for the entire operation. The authentic environment and ease of highway access are major draws for tourists.

Another way to consider Nevada City is how heritage tourism ideas of the 1960s–especially the idea of excursion passenger trains–impacted the built environment. What is now known as Alder Gulch Railroad started c. 1964, a way of attracting visitors to stop in Nevada City where then they could take the short ride to Virginia City.

Another way to consider Nevada City is how heritage tourism ideas of the 1960s–especially the idea of excursion passenger trains–impacted the built environment. What is now known as Alder Gulch Railroad started c. 1964, a way of attracting visitors to stop in Nevada City where then they could take the short ride to Virginia City.

telling example of how historic preservation worked in the West, a true public-private partnership, in the years immediately before the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966.

telling example of how historic preservation worked in the West, a true public-private partnership, in the years immediately before the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

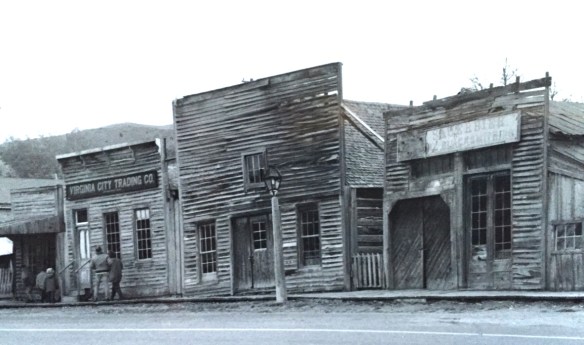

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.