U.S. Highway 2 east of Kalispell has grown into a four-lane highway (mostly–topography thus far has kept it as a two-lane stretch west of Hungry Horse) designed to move travelers back and forth from Kalispell to Glacier National Park. In my 1984-85 state historic preservation plan work, I thought of Columbia Falls, Hungry Horse, and Martin

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

There is much more than the highway to Columbia Falls, as the three building blocks above indicate, not to mention the lead image of this blog, the town’s Masonic Lodge which has been turned into one huge public art mural about the town’s history as well as its surrounding landscape. Go to the red brick Bandit’s Bar above, and you soon discover that Columbia Falls has a good sense of itself, and even confidence that it can survive new challenges as its population has soared by over 2,000 residents since the 1980s, totaling over 5,000 today.

Once solely dependent on the Montana Veterans’ Home (1896), which is now a historic district, and then relying on the Weyerhaeuser sawmill for year round employment, Columbia Falls faces a different future now once the mill closed in the summer of 2016, taking away 200 jobs. As the historic business buildings above indicate, historic preservation could be part of that future, as the downtown’s mix of classic Western Commercial blocks mesh with modern takes on Rustic and Contemporary design and are complemented, in turn, by historic churches and the Art Deco-influenced school.

Once you leave the highway, in other words, real jewels of turn of the 20th century to mid-20th century design are in the offing. In 1984–I never looked that deep.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

Here I am thinking primarily of the contemporary design of the Visitors Center–its stone facade suggesting its connection to the now covered river bluffs but the openness of its interior conveying the ideas of space associated with 1950s design.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

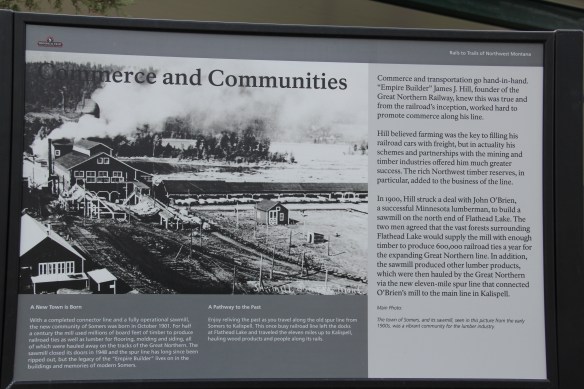

Martin City is just enough off of U.S. Highway 2–it is situated more on the historic Great Northern Railroad corridor–to miss out on the gateway boom of the last 30 years, although with both the Southfork Saloon and the Deer Lick Saloon it retains its old reputation as a rough-edged place for locals.

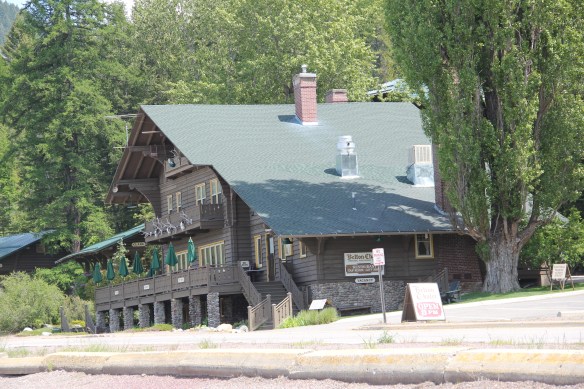

For railroad travelers in the first half of the 20th century, West Glacier was THE west gateway into Glacier National Park. The Great Northern Railway developed both the classic Rustic-styled passenger station and the adjacent Arts and Crafts/Chalet styled Belton Chalet Hotel in 1909-1910, a year before Congress created Glacier National Park.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

The Cutter buildings for the railroad between 1909-1913 set a design standard for West Glacier to follow, be it through a modern-day visitor center and a post office to the earlier mid-20th century era of the local school and then gas stations and general stores for tourists entering the national park by automobile.

This blog has never hidden the fact, however, that my favorite Glacier gateway in Flathead County is miles to the east along U.S. Highway 2 at the old railroad town of Essex, where the railroad still maintains facilities to help push freight trains over the Continental Divide. The Izaak Walton Inn was one of the first National Register assignments given to

me by State Historic Preservation Officer Marcella Sherfy–find the facts, she asked, to show that this three story bunk house, railroad offices, and local post merited exceptional significance for the National Register. Luckily I did find those facts and shaped that argument–the owners then converted a forgotten building into a memorable historical experience. Rarely do I miss a chance to spend even a few minutes here, to watch and hear the noise of the passing trains coming from the east or from the west and to catch a sunset high in the mountains of Flathead County.

Conrad, the seat of Pondera County, is a railroad town, although the town’s close proximity to Interstate I-15 means that so many have forgotten the importance of this Great Northern Railway spur line that stretches from Shelby on the main line south to Great Falls.

Conrad, the seat of Pondera County, is a railroad town, although the town’s close proximity to Interstate I-15 means that so many have forgotten the importance of this Great Northern Railway spur line that stretches from Shelby on the main line south to Great Falls.

The town’s 1920s Arts and Crafts/ Chalet style Great Northern passenger station, along with grain elevators, serve as a reminder of the railroad’s importance to transporting the grains from neighboring ranches.

The town’s 1920s Arts and Crafts/ Chalet style Great Northern passenger station, along with grain elevators, serve as a reminder of the railroad’s importance to transporting the grains from neighboring ranches. Facing the depot is a combination symmetrical town, with one story brick buildings, several of them classic western bars, and then a block long T-plan that connects to the historic federal highway U.S. 87.

Facing the depot is a combination symmetrical town, with one story brick buildings, several of them classic western bars, and then a block long T-plan that connects to the historic federal highway U.S. 87.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

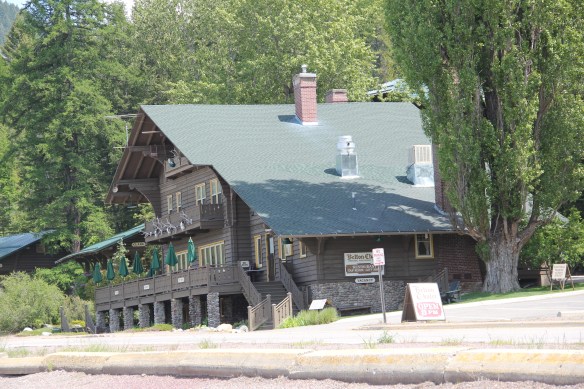

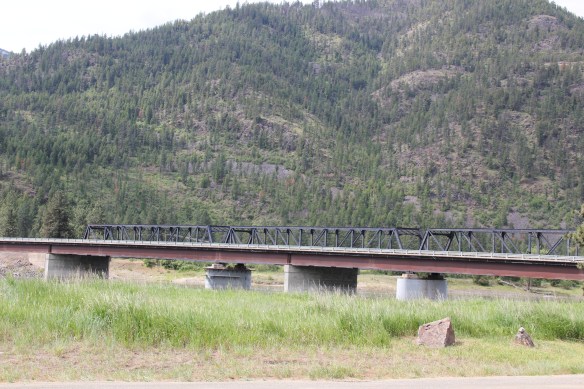

The answer was yes, to both questions. Here is an early 20th century log building landmark on a highway where the traffic seems to never end. It is also along the corridor of a new recreational system–the Great Northern Rails to Trails linear park that uses an old railroad corridor to connect the city to the country in Flathead County.

The answer was yes, to both questions. Here is an early 20th century log building landmark on a highway where the traffic seems to never end. It is also along the corridor of a new recreational system–the Great Northern Rails to Trails linear park that uses an old railroad corridor to connect the city to the country in Flathead County.

The trail allows bikers to see the rural landscape, still dotted with family farms, of the Smith Valley as it stretches west to Kila, where the old Cottage Inn has been converted in the last few years into the Kila Pub, complete with the Arts and Crafts/Tudor theme associated with the railroad corridor.

The trail allows bikers to see the rural landscape, still dotted with family farms, of the Smith Valley as it stretches west to Kila, where the old Cottage Inn has been converted in the last few years into the Kila Pub, complete with the Arts and Crafts/Tudor theme associated with the railroad corridor.

To the north of Kalispell and Whitefish U.S. Highway 93 takes you past the ski developments into a thick forested area, managed in part as the Stillwater State Forest.

To the north of Kalispell and Whitefish U.S. Highway 93 takes you past the ski developments into a thick forested area, managed in part as the Stillwater State Forest.

from the 1920s into the 1960s. While several are from the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s, state ranger Pete De Groat built his log residence in 1928 in the Rustic Style. Stillwater was Montana’s first state forest.

from the 1920s into the 1960s. While several are from the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s, state ranger Pete De Groat built his log residence in 1928 in the Rustic Style. Stillwater was Montana’s first state forest.

“lone eagles” was local–an attempt to describe those professionals “who fly to work as comfortably as most Americans drive, and whose use of computers in business lets them indulge their preference for life in the great outdoors,” as a June 19, 1994 story in the New York Times explained.

“lone eagles” was local–an attempt to describe those professionals “who fly to work as comfortably as most Americans drive, and whose use of computers in business lets them indulge their preference for life in the great outdoors,” as a June 19, 1994 story in the New York Times explained.

The station along with the railroad tracks defined everything you saw in Whitefish–here in the classic Great Northern T-plan landscape was a classic railroad town–one that old-timers even called the best along the entire line. Whitefish developed and then prospered as a division point on the mainline from 1904 to 1955–and that corporate imprint was still there to be experienced, in 1984.

The station along with the railroad tracks defined everything you saw in Whitefish–here in the classic Great Northern T-plan landscape was a classic railroad town–one that old-timers even called the best along the entire line. Whitefish developed and then prospered as a division point on the mainline from 1904 to 1955–and that corporate imprint was still there to be experienced, in 1984. Thankfully in 2015, I still found all of my favorite landmarks from 30 years earlier, even though there was little doubt that the business district had been altered, sometimes in ways that left little original fabric in place but still some two-story brick blocks stood.

Thankfully in 2015, I still found all of my favorite landmarks from 30 years earlier, even though there was little doubt that the business district had been altered, sometimes in ways that left little original fabric in place but still some two-story brick blocks stood.

A much earlier landmark, the Classical Revival Masonic Temple from the town’s first decade still stood, and it too found a new use through adaptive reuse.

A much earlier landmark, the Classical Revival Masonic Temple from the town’s first decade still stood, and it too found a new use through adaptive reuse. Despite the population boom over the last 30 years, Whitefish still uses its Art Deco-styled school from the New Deal decade of the 1930s, although the auditorium has been restored and updated into a community performing arts center.

Despite the population boom over the last 30 years, Whitefish still uses its Art Deco-styled school from the New Deal decade of the 1930s, although the auditorium has been restored and updated into a community performing arts center.

By the late 1980s there was little doubt that a substantial development boom was underway in Flathead County. In the town near the Flathead Lake, like Bigfork, above, the boom dramatically altered both the density and look of the town. In the northern half of the county Whitefish suddenly became a sky resort center. In 1988, during a return visit to Montana, I did not like what I encountered in Flathead County–and thus I stayed away for the next 27 years years, until the early summer of 2015.

By the late 1980s there was little doubt that a substantial development boom was underway in Flathead County. In the town near the Flathead Lake, like Bigfork, above, the boom dramatically altered both the density and look of the town. In the northern half of the county Whitefish suddenly became a sky resort center. In 1988, during a return visit to Montana, I did not like what I encountered in Flathead County–and thus I stayed away for the next 27 years years, until the early summer of 2015.

I love Montana town signs, and Troy, deep in the state’s logging country, has one of the best. The sign lures to a city park nestled along the Kootenai River. The focus point is a

I love Montana town signs, and Troy, deep in the state’s logging country, has one of the best. The sign lures to a city park nestled along the Kootenai River. The focus point is a

the Great Northern’s main line, and I documented the few historic buildings left facing the railroad tracks today. The Home Bar (c. 1914) and the Club Bar were institutions then, and remain so today. The Kootenai State Bank building still stands but has experienced a major change to its facade–made better in part by the American flag painted over some of the frame addition.

the Great Northern’s main line, and I documented the few historic buildings left facing the railroad tracks today. The Home Bar (c. 1914) and the Club Bar were institutions then, and remain so today. The Kootenai State Bank building still stands but has experienced a major change to its facade–made better in part by the American flag painted over some of the frame addition. The Troy Jail, above, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and it remains the only building so listed in the town today. D.E. Crissey, a local contractor, built it out of concrete in 1924 during Troy’s boom from 1916 to 1926 when its population jumped from 300 to 1300. The Snowstorm mine, which produced lead, zinc, and silver, started to serve the demand for raw materials during World War I. The mine soon turned what had been a small railroad town into a mining camp best known for its brothels and bars. Then in the early 1920s the Great Northern decided to build a division point here, further booming the town. The Sandpoint Pole and Lumber Company began its logging business in 1923, and Troy suddenly was the largest town in the county

The Troy Jail, above, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2006 and it remains the only building so listed in the town today. D.E. Crissey, a local contractor, built it out of concrete in 1924 during Troy’s boom from 1916 to 1926 when its population jumped from 300 to 1300. The Snowstorm mine, which produced lead, zinc, and silver, started to serve the demand for raw materials during World War I. The mine soon turned what had been a small railroad town into a mining camp best known for its brothels and bars. Then in the early 1920s the Great Northern decided to build a division point here, further booming the town. The Sandpoint Pole and Lumber Company began its logging business in 1923, and Troy suddenly was the largest town in the county

Libby is the seat of Lincoln County, a typical railroad town along the historic Great Northern Railway corridor. The image above is from the town’s railroad depot, the symbolic beginning of town, from which runs a long main street of businesses, reflecting the T-plan town design, where the long railroad corridor defines the top of the T and the main street forms the stem of the T.

Libby is the seat of Lincoln County, a typical railroad town along the historic Great Northern Railway corridor. The image above is from the town’s railroad depot, the symbolic beginning of town, from which runs a long main street of businesses, reflecting the T-plan town design, where the long railroad corridor defines the top of the T and the main street forms the stem of the T.

courthouse received a totally new front, in a contemporary style, in the 1970s as the town and county expanded in the wake of the federal spending in constructing Libby Dam. The rectangular blockiness, flat roof, and band of windows set within a symmetrical facade makes the courthouse one of the state’s best designs for a rural public building in the late 20th century.

courthouse received a totally new front, in a contemporary style, in the 1970s as the town and county expanded in the wake of the federal spending in constructing Libby Dam. The rectangular blockiness, flat roof, and band of windows set within a symmetrical facade makes the courthouse one of the state’s best designs for a rural public building in the late 20th century. I liked all of those things about Libby in 1984. Imagine my shock and disappointment to learn, as everyone else did, that Libby was one of the poisoned places in the west. In 1919, vermiculite, a natural material that contains asbestos, had been discovered outside of town, and the mines were still operating, producing 80 percent of the vermiculite in the world, under the control of the W.R. Grace company. Residue from the mines had been used in local yards and buildings for decades, a fact that was not known when I visited the town for the state historic preservation plan. When the discovery of the danger became public, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency entered into the fray in 1999, it was already too late for many residents. A federal Superfund project began, and did not conclude its work until 2015, spending some $425 million. Then in 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency announced a public health emergency, spending another $130 million to help residents and to leave a new health infrastructure in place. In a generation, Libby had been turned inside out. EPA announced in 2016 that the cleanup would continue to 2018, and that the project was the longest in the agency’s history.

I liked all of those things about Libby in 1984. Imagine my shock and disappointment to learn, as everyone else did, that Libby was one of the poisoned places in the west. In 1919, vermiculite, a natural material that contains asbestos, had been discovered outside of town, and the mines were still operating, producing 80 percent of the vermiculite in the world, under the control of the W.R. Grace company. Residue from the mines had been used in local yards and buildings for decades, a fact that was not known when I visited the town for the state historic preservation plan. When the discovery of the danger became public, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency entered into the fray in 1999, it was already too late for many residents. A federal Superfund project began, and did not conclude its work until 2015, spending some $425 million. Then in 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency announced a public health emergency, spending another $130 million to help residents and to leave a new health infrastructure in place. In a generation, Libby had been turned inside out. EPA announced in 2016 that the cleanup would continue to 2018, and that the project was the longest in the agency’s history.

Despite the disaster, I saw many signs that Libby residents were determined to remain and rebuild their community. One of the most powerful examples is the conversion of one of the town’s historic schools into a new community arts center as well as school administration offices.

Despite the disaster, I saw many signs that Libby residents were determined to remain and rebuild their community. One of the most powerful examples is the conversion of one of the town’s historic schools into a new community arts center as well as school administration offices.

The asbestos crisis was a terrible disaster for Libby–yet residents refused to let it define their future. There are past accomplishments to acknowledge, an active railroad depot to cherish, a beautiful river and lake, the mountains all around, as celebrated in this public art mural on a downtown building. This place is here to stay, and the historic built environment is a large part of it.

The asbestos crisis was a terrible disaster for Libby–yet residents refused to let it define their future. There are past accomplishments to acknowledge, an active railroad depot to cherish, a beautiful river and lake, the mountains all around, as celebrated in this public art mural on a downtown building. This place is here to stay, and the historic built environment is a large part of it.

Moiese is best known, by far, as the entrance to the National Bison Range, where a general store stands nearby the refuge gate. Created by Congress in 1908, the refuge took

Moiese is best known, by far, as the entrance to the National Bison Range, where a general store stands nearby the refuge gate. Created by Congress in 1908, the refuge took

additional land–almost 19,000 acres- from the tribes, without their consent, to create a safe haven for the remaining bison in the region. A few hundred bison live within its boundaries today. In 2016 the National Park Service began discussions with the Consolidated Kootenai and Salish Tribe to transfer management of the refuge to the tribe.

additional land–almost 19,000 acres- from the tribes, without their consent, to create a safe haven for the remaining bison in the region. A few hundred bison live within its boundaries today. In 2016 the National Park Service began discussions with the Consolidated Kootenai and Salish Tribe to transfer management of the refuge to the tribe. Eight miles north of Moiese along the railroad line is the town of Charlo, named in honor of Chief Charlo of the Bitterroot Salish, who was forced from the Bitterroot Valley to move to the reservation in 1891. Charlo served as head chief of the Bitterroot Salish from 1870-

Eight miles north of Moiese along the railroad line is the town of Charlo, named in honor of Chief Charlo of the Bitterroot Salish, who was forced from the Bitterroot Valley to move to the reservation in 1891. Charlo served as head chief of the Bitterroot Salish from 1870- 1910. As a railroad town, Charlo is like many along the Northern Pacific, with a brief strip of businesses facing the railroad tracks, marked by the town’s sole grain elevator. It has a classic rural bar, Tiny’s Tavern, with its brightly painted exterior of concrete block, with brick accents. Built in 1946 by Tiny Browne, it was both a motel and a tavern, and a local museum of items that Tiny thought were interesting. Browne died in 1977 and his sister, Celeste Fagan, next owned the tavern, managed by Edna Easterly who recalled in a story in the Missoulian of April 20, 2007 that Tiny “was known as the bank of Charlo. Tiny always carried a lot of money in his pocket and if you needed to cash a check, you went to Tiny.”

1910. As a railroad town, Charlo is like many along the Northern Pacific, with a brief strip of businesses facing the railroad tracks, marked by the town’s sole grain elevator. It has a classic rural bar, Tiny’s Tavern, with its brightly painted exterior of concrete block, with brick accents. Built in 1946 by Tiny Browne, it was both a motel and a tavern, and a local museum of items that Tiny thought were interesting. Browne died in 1977 and his sister, Celeste Fagan, next owned the tavern, managed by Edna Easterly who recalled in a story in the Missoulian of April 20, 2007 that Tiny “was known as the bank of Charlo. Tiny always carried a lot of money in his pocket and if you needed to cash a check, you went to Tiny.” Most important for its architecture, however, is the town’s public school, a wonderful example of Art Deco style from the New Deal decade of the 1930s.

Most important for its architecture, however, is the town’s public school, a wonderful example of Art Deco style from the New Deal decade of the 1930s. Ronan is a third town along the railroad corridor, named for a former white superintendent of the reservation. The town’s demographics today are mostly white, with a little more than a quarter Native American population. Ronan proudly proclaims its existence not only with a gate sign, connecting the business district to the sprawl along U.S. Highway 93 but also a log visitor center and interpretive park on the highway.

Ronan is a third town along the railroad corridor, named for a former white superintendent of the reservation. The town’s demographics today are mostly white, with a little more than a quarter Native American population. Ronan proudly proclaims its existence not only with a gate sign, connecting the business district to the sprawl along U.S. Highway 93 but also a log visitor center and interpretive park on the highway.

The facade expresses a confident future, which is needed in today’s uncertain economic climate for rural hospitals across the state. But my favorite building in Ronan speaks to my love for adaptive reuse and mid-20th century modern design. The town library is an

The facade expresses a confident future, which is needed in today’s uncertain economic climate for rural hospitals across the state. But my favorite building in Ronan speaks to my love for adaptive reuse and mid-20th century modern design. The town library is an exquisite example of mid-century modern, and was once a local bank before being converted into the library.

exquisite example of mid-century modern, and was once a local bank before being converted into the library.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core. The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century. Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks.

Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks. But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

Sanders County, like many of the places that are on the western side of the Rocky Mountains, has boomed in the last 25 years, from a population over 8,000 to the current estimated population of 11,300. It is close to Missoula, the eastern side is not far from Flathead Lake, Montana Highway 200 runs from Dixon to the end of the county at Heron. With wide valleys and narrow gorges created by both the Flathead and Clark’s Fork Rivers, which meet outside the town of Paradise, Sanders County is frankly a spectacular landscape, with dramatic mountain views framing open plains, such as the image above and the awesome gorge of Clark’s Fork River, below at Thompson Falls.

Sanders County, like many of the places that are on the western side of the Rocky Mountains, has boomed in the last 25 years, from a population over 8,000 to the current estimated population of 11,300. It is close to Missoula, the eastern side is not far from Flathead Lake, Montana Highway 200 runs from Dixon to the end of the county at Heron. With wide valleys and narrow gorges created by both the Flathead and Clark’s Fork Rivers, which meet outside the town of Paradise, Sanders County is frankly a spectacular landscape, with dramatic mountain views framing open plains, such as the image above and the awesome gorge of Clark’s Fork River, below at Thompson Falls. The eastern side of the county is just as dramatic just in a far different way. For centuries First Peoples hunted game and dug the camas root in the broad upland prairie that became known as Camas Prairie, crossed now by Montana Highway 28.

The eastern side of the county is just as dramatic just in a far different way. For centuries First Peoples hunted game and dug the camas root in the broad upland prairie that became known as Camas Prairie, crossed now by Montana Highway 28. Then, leading from the county’s southeastern edge there is the beautiful Flathead River Valley, followed by Montana Highway 200, from Dixon to Paradise, and most importantly,

Then, leading from the county’s southeastern edge there is the beautiful Flathead River Valley, followed by Montana Highway 200, from Dixon to Paradise, and most importantly, a transportation route initially carved as a trail by the First Peoples who became the nucleus of today’s Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe and much later engineered into a major corridor by the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, as it stretched westward from Missoula to the west coast.

a transportation route initially carved as a trail by the First Peoples who became the nucleus of today’s Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe and much later engineered into a major corridor by the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, as it stretched westward from Missoula to the west coast. In its wake, the Northern Pacific created most of the county’s townsites by locating sidings along the track. Substantial settlement arrived once the federal government opened lands for the homesteading boom in the early 20th century.

In its wake, the Northern Pacific created most of the county’s townsites by locating sidings along the track. Substantial settlement arrived once the federal government opened lands for the homesteading boom in the early 20th century. Dixon, named for the former Montana governor Joseph Dixon, is one of the remaining railroad/homesteading towns along the Flathead River. The fate of the community bar, above, is symbolic of the recent history of the town, one of population decline.

Dixon, named for the former Montana governor Joseph Dixon, is one of the remaining railroad/homesteading towns along the Flathead River. The fate of the community bar, above, is symbolic of the recent history of the town, one of population decline.

Local residents are being excellent stewards of this captivating property–certainly one of my favorite spots in the state combining landscape with architecture with history. The architect was the Missoula designer H. E. Kirkemo, and the school was completed in 1940, near the end of the New Deal school building programs.

Local residents are being excellent stewards of this captivating property–certainly one of my favorite spots in the state combining landscape with architecture with history. The architect was the Missoula designer H. E. Kirkemo, and the school was completed in 1940, near the end of the New Deal school building programs.

The school had just closed its doors for good when I lasted visited but the restoration planning has been underway ever since. I look forward to my next visit to Paradise to experience the final results. Near the school is another historic community property, the Paradise Cemetery, where tombstones mark the names of those who worked so long for the railroad and for the creation of this place within the Clark’s Fork River Valley.

The school had just closed its doors for good when I lasted visited but the restoration planning has been underway ever since. I look forward to my next visit to Paradise to experience the final results. Near the school is another historic community property, the Paradise Cemetery, where tombstones mark the names of those who worked so long for the railroad and for the creation of this place within the Clark’s Fork River Valley.