Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Wibaux ranch house, 1985.

When I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, a handful of ranches had been preserved as museums. On the eastern end of the state in Wibaux was the preserved ranch house of Pierre Wibaux, one of the 1880s cattle barons of eastern Montana and western North Dakota. The ranch house today remains as a historic site, and a state welcome center for interstate travelers–although you wish someone in charge would remove the rather silly awning from the gable end window.

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

not only preserves one of the earliest settlement landscapes in the state it also shows how successful ranches change over time. John Grant began the place before the Civil War: he was as much an Indian trader than ranch man. Grant Kohrs however looked at the rich land, the railroad line that ran through the place, and saw the potential for becoming a cattle baron in the late 19th century. To reflect his prestige and for his family’s comfort, the old ranch house was even updated with a stylish Victorian brick addition. The layers of history within this landscape are everywhere–not surprisingly. There is a mix of 19th and 20th century buildings here that you often find at any historic ranch.

When I was working with the Montana Historical Society in 1984-1985 there were two additional grand ranches that we thought could be added to the earlier preservation achievements. Both are now landmarks, important achievements of the last 30 years.

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

Here was one of the grand showplace ranches of the American West, with its own layers of a grand Queen Anne ranch house (still marked by the Shingle-style laundry house) of Daly’s time that was transformed into an even greater Classical Revival mansion by his Margaret Daly after her husband’s death. It is with us today largely due to the efforts of a determined local group, with support from local, state, and federal governments, a group of preservation non-profits, and the timely partnership of the University of Montana.

The second possibility was also of the grand scale but from more recent times–the Bair Ranch in Martinsdale, almost in the center of the state. Charles Bair had made his money in sheep and wise investments. His daughters traveled the world and brought treasures home to their Colonial Revival styled ranch house. To get a chance to visit with Alberta Bair here in the mid-1980s was a treat indeed.

Once again, local initiative preserved the ranch house and surrounding buildings and a local board operates both a house museum and a museum that highlights items from the family’s collections.

The success of the Bitter Root Stock Farm and the Bair Ranch was long in the making, and you hope that both can weather the many challenges faced by our public historic sites and museums today. We praise our past but far too often we don’t want to pay for it.

That is why family stewardship of the landscape is so important. Here are two examples from Beayerhead County. The Tash Ranch (above and below) is just outside of Dillon and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. But is also still a thriving family ranch.

The same is true for the Bremmer Ranch, on the way to Lemhi Pass. Here is a family still using the past to forge their future and their own stories of how to use the land and its resources to maintain a life and a culture.

One family ranch that I highlighted in my book, A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986), was the Simms-Garfield Ranch, located along the Musselshell River Valley in Golden Valley County, along U.S. Highway 12. This National Register-property was not, at

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

Similar traditions are expressed in another way at a more recent National Register-listed ranch, the Vogt-Nunberg Ranch south of Wibaux on Montana Highway 7. Actively farmed from 1911 to 1995, the property documents the changes large and small that happened in Montana agriculture throughout the 20th century.

The stories of these ranches are only a beginning. The Montana Preservation Alliance has done an admirable job of documenting the state’s historic barns, and the state historic preservation office has listed many other ranches to the National Register. But still the rural landscape of the Big Sky Country awaits more exploration and understanding.

The town’s grain elevators really are its landmark–the town is along the railroad spur and sits off Montana Highway 16–without the elevators you might not even notice it.

The town’s grain elevators really are its landmark–the town is along the railroad spur and sits off Montana Highway 16–without the elevators you might not even notice it. Agriculture defines the use of the largest buildings of the town, and while it is a tiny place Reserve serves a much larger region of ranches located between Plentywood, the county seat, to the north and Medicine Lake, to the south.

Agriculture defines the use of the largest buildings of the town, and while it is a tiny place Reserve serves a much larger region of ranches located between Plentywood, the county seat, to the north and Medicine Lake, to the south. This larger audience for services in Reserve helps to explain the survival of the Reserve Post Office–so many tiny Montana towns have lost the one federal institution that had been there since the town’s beginning.

This larger audience for services in Reserve helps to explain the survival of the Reserve Post Office–so many tiny Montana towns have lost the one federal institution that had been there since the town’s beginning. But naturally I will urge you to make a stop, however brief, at the Reserve Bar. This concrete block building, with its period glass block windows, is a friendly place, and a great way to talk with both residents and surrounding farmers.

But naturally I will urge you to make a stop, however brief, at the Reserve Bar. This concrete block building, with its period glass block windows, is a friendly place, and a great way to talk with both residents and surrounding farmers.

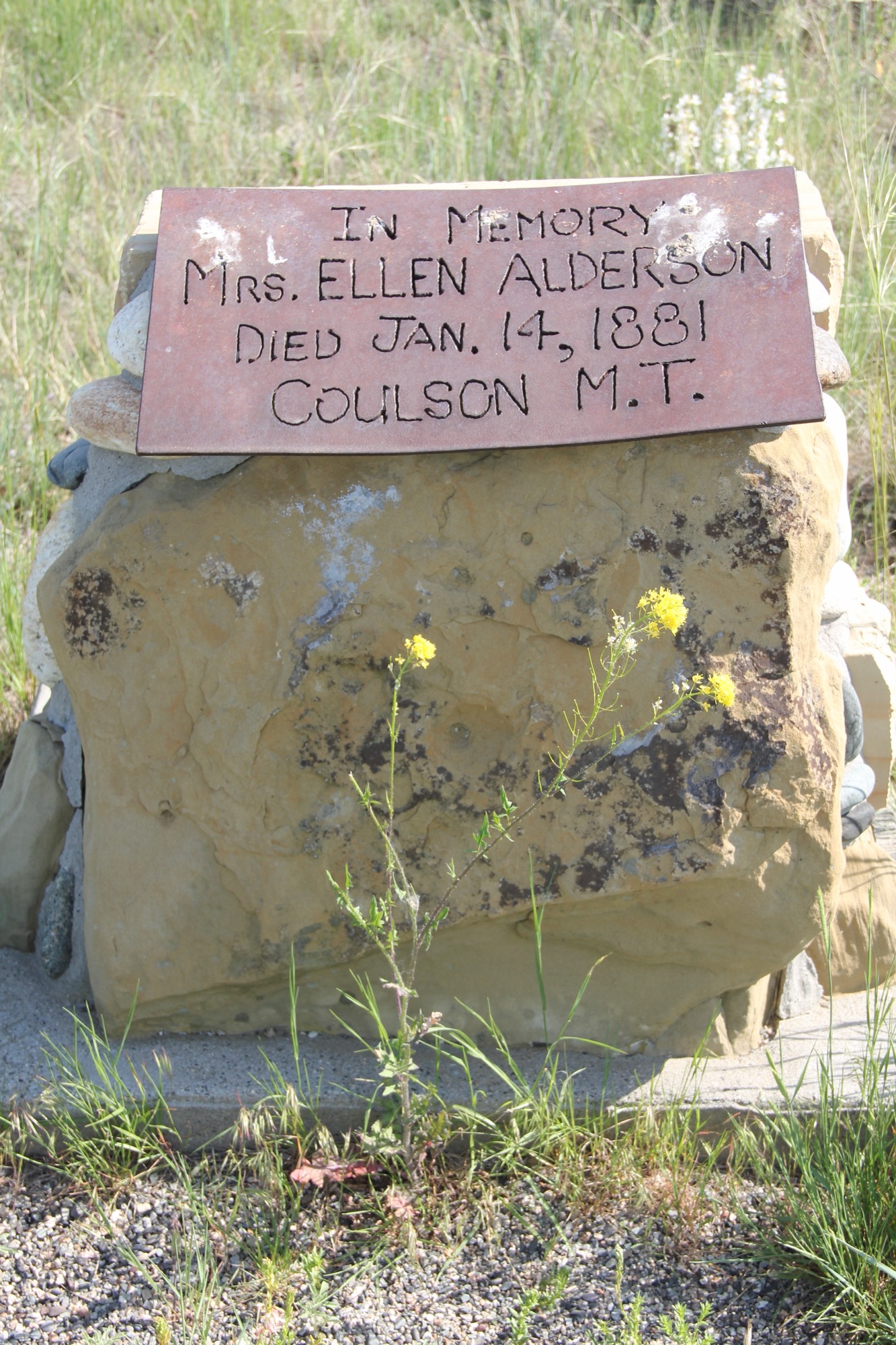

On the northwestern outskirts of Livingston is Mountain View Cemetery, another of the historic properties that certainly existed when I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, but since it was a cemetery, we as a field gave it, or any cemetery for that matter, little consideration thirty years ago.

On the northwestern outskirts of Livingston is Mountain View Cemetery, another of the historic properties that certainly existed when I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, but since it was a cemetery, we as a field gave it, or any cemetery for that matter, little consideration thirty years ago.

This brief overview does not do justice to the city’s historic cemeteries. Certainly I gave Boothill consideration in the 1984-1985 and even wrote about it in both of my books on Billings history. But Mountview is a historic landscape that only now I recognize–and I hope to do more exploration in the future.

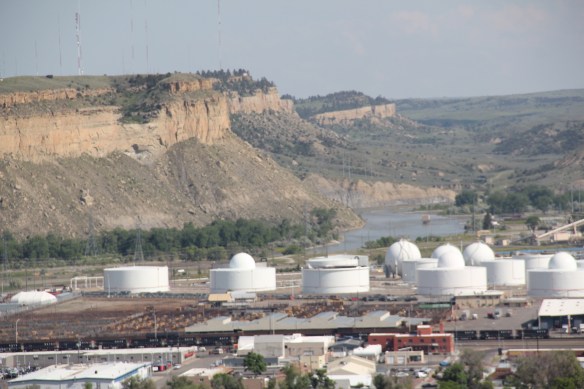

This brief overview does not do justice to the city’s historic cemeteries. Certainly I gave Boothill consideration in the 1984-1985 and even wrote about it in both of my books on Billings history. But Mountview is a historic landscape that only now I recognize–and I hope to do more exploration in the future. The last post addressed Montana’s famous ranching landscape. Intermixed with the ranches, especially in the eastern third of the state, is a very different landscape of technology, one of pumps, storage facilities, pipelines, and refineries–the oil landscape of 20th and 21st century Montana.

The last post addressed Montana’s famous ranching landscape. Intermixed with the ranches, especially in the eastern third of the state, is a very different landscape of technology, one of pumps, storage facilities, pipelines, and refineries–the oil landscape of 20th and 21st century Montana.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley. The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

Bozeman has boomed with many new chef-driven restaurants but of the downtown establishments my favorite for good fresh, creative food remains the Co-Op Downtown nestled within the Gallatin Block, a historic building, tastefully renovated, in the downtown historic district.

Bozeman has boomed with many new chef-driven restaurants but of the downtown establishments my favorite for good fresh, creative food remains the Co-Op Downtown nestled within the Gallatin Block, a historic building, tastefully renovated, in the downtown historic district.

head to Miles City, which is the place to go if you wonder, still, “where’s the beef” and a city that is the proud home of the famous Montana Bar.

head to Miles City, which is the place to go if you wonder, still, “where’s the beef” and a city that is the proud home of the famous Montana Bar.

within New Deal landscape that forever changed the look of this region in the 1930s. Locals and tourists mix together–because the hotel is the only place to go, unless you want to backtrack to Glasgow and check out Sam’s Supper Club on U.S. Highway 2, and its equally neat 1960s roadside look.

within New Deal landscape that forever changed the look of this region in the 1930s. Locals and tourists mix together–because the hotel is the only place to go, unless you want to backtrack to Glasgow and check out Sam’s Supper Club on U.S. Highway 2, and its equally neat 1960s roadside look.