In my 1984 fieldwork, Havre was a base for quite a bit of travel along the Hi-Line. One of the most compelling landscapes, and among my favorites for the state, were the little towns, regularly spaced about every eight miles, west of Havre.

At the time, my understanding of this landscape was heavily influenced by recent works by the American Studies scholar John Stilgoe (Metropolitan Corridor: Railroads and the American Scene) and the historical geographer John Hudson (a series of articles that culminated in the book Plains Country Towns.) Stilgoe reminded me that railroads in the late 19th century not only defined towns and urban design but impacted American culture in how small, tiny spaces became part of urban, metropolitan life through the steel tracks. Hudson explain why towns existed every six to seven miles or so throughout the plains (these were often single track lines so trains needed places to pull over for passing, and places where water and fuel could be acquired as necessary). Hudson explained differences between railroad division points, where shops and offices would be located, and “country towns,” where typically a combination depot carried out all of the railroad’s corporate functions.

This arrangement of space, and the ennobling of railroad culture in larger towns, was exactly what I saw in Havre and Hill County. Ever since 1984, this has been among my favorite places in Montana. In a posting last year I discussed the “disappearing depots” along the Hi-Line, focusing on west Hill County. I want to revisit those same places today, with a deeper view on what was there in 1984 and what you find today.

Inverness, established c. 1909, was the first place I stopped but spent little time there because already in 1984 its Great Northern depot was gone. But in 2013, I was looking for beyond the Stilgoe-Hudson way of understanding plains country towns. Inverness in 2010 had 55 residents, but still held several early settlement landmarks, such as its early 20th century elevators along the railroad, a National Register-quality c. 1920 store/gas station, and two large two-story frame blocks–the historic Inverness Hotel (most recently Inverness Supper Club) dates to the second decade of the 20th century.

The Sacred Heart Catholic Church dates to the town’s beginnings, but a brick school from 1931 with 1952 additions closed in the early 21st century.

Inverness’s c. 1960 post office is a great example of stone-faced standardized design that the postal service used in small towns across the nation in that decade. It was one of the offices threatened with closure in 2011.

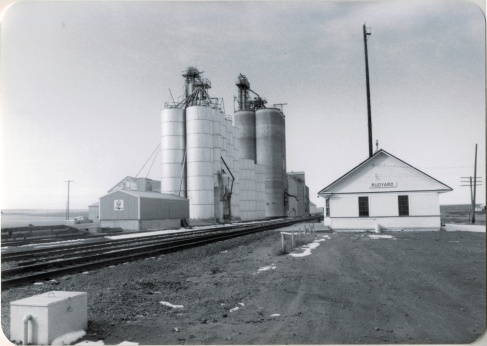

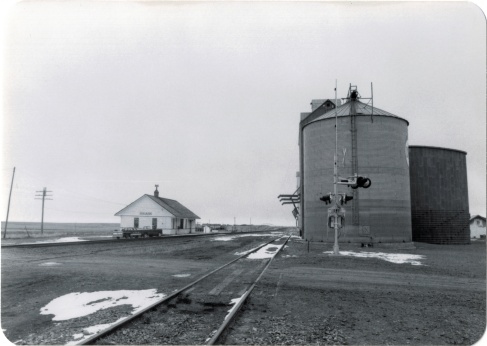

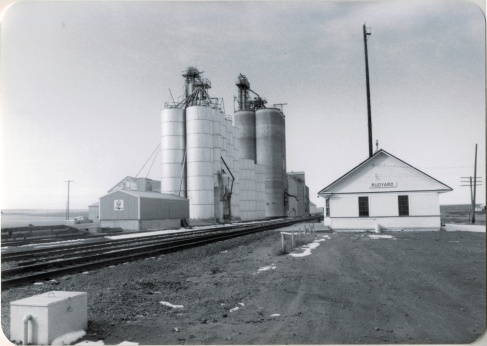

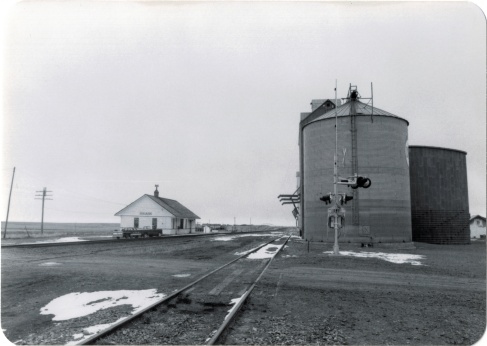

Rudyard, established 1909, was the largest of the west Hill County towns, about 500 people in 1980 but now with only 258 residents according to the 2010 census. Its prominence in the second half of the 20th century is reflected in two buildings: the tall concrete grain elevators along the railroad and the contemporary-styled Wells Fargo bank building on the prominent town corner facing the tracks and Reed Street.

Thirty years ago, as the construction of a modern bank building attests, several stores and the Hi-Line Theater were hubs of activity; today most businesses are closed.

Museums now abound–with the moved depot forming a small building zoo while an early 20th century stone building has become an auto museum.

Rudyard also has one of the highway’s most famous town signs–boasting of a population now greatly diminished but the old sorehead remains–at the Sorehead Cafe in the heart of the four block long commercial district.

One hundred years ago, Hingham (1910) seemed to be the town that would make it. From the railroad corridor several blocks of commercial businesses were filled in the next decade.

There was a town square featuring a city park in the midst of it all.

Here the town’s Commercial Club hosted the Hi-Line Fair, which “presented farmers and ranchers with an opportunity to exhibit their grain and livestock and to exchange ideas with people from other points along the Hi-Line.”

While the buildings, outside of the brick neo-classical brick bank (1913-14), were frame, town boosters were confident these were only the initial businesses. But the second decade of the 20th century proved to be the town’s high point, and frame buildings still define local businesses.

In 1930 they defined the town with a large, handsome two-story brick school at its south end (near U.S. 2, a recognition of the highway’s importance in getting students to and from Hingham).

The Our Lady of Ransom Catholic Church is a modernist landmark, and one of the most architecturally important buildings of the Hi-Line, part of the Great Falls diocese effort to improve and modernize its churches in the mid-20th century. A much earlier frame Methodist Church remains, and has most recently served as a community chapel.

The boosters of Gildford also had high hopes in 1910 and the homesteading boom brought a full fledged town into existence by 1915-16.

Elevators in 1985

Elevators in 1985

The boom decade is marked by the extant Gildford State Bank (1914), which also served as the town’s post office when I first visited in 1984. The town also had an early industry, the Mundy Flour Mill.

Kremlin acknowledges its distinct name with its highway town sign.

Settlement began in 1909, with a plat from land agent K.C. Farley, focused on the Great Northern section house, later replaced by a standardized depot, all of which is gone from the railroad corridor today.

The WPA built a new high school in 1938, which remains a central landmark for the community, a symbol of the future, and a good way to end this posting.

All of Glacier National Park is spectacular, frankly, but as you reach Logan Pass and consider the historic architecture on the east side of the park, often the landscape itself overpowers the man-made environment, be it the modernist visitor center at Logan Pass, above to the left of center of the image, or the Many Glacier Hotel on the north end of the park, below. The manmade is insignificant compared to the grandeur of the mountains.

All of Glacier National Park is spectacular, frankly, but as you reach Logan Pass and consider the historic architecture on the east side of the park, often the landscape itself overpowers the man-made environment, be it the modernist visitor center at Logan Pass, above to the left of center of the image, or the Many Glacier Hotel on the north end of the park, below. The manmade is insignificant compared to the grandeur of the mountains. The reverse is true at East Glacier, where the mammoth Glacier Park Lodge competes with the surrounding environment. The massive log hotel was the brainchild of Louis Hill, the president of the Great Northern Railway, who wished for a building that could mirror the earlier 1905 Forestry Hall for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. Hill had the vision but architect Samuel L. Bartlett of St. Paul, Minnesota, carried the vision into an architectural plan.

The reverse is true at East Glacier, where the mammoth Glacier Park Lodge competes with the surrounding environment. The massive log hotel was the brainchild of Louis Hill, the president of the Great Northern Railway, who wished for a building that could mirror the earlier 1905 Forestry Hall for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. Hill had the vision but architect Samuel L. Bartlett of St. Paul, Minnesota, carried the vision into an architectural plan.

But the long landscaped walkway from the Glacier Park Lodge to the Great Northern passenger station, also themed in Rustic style, let everyone know who was in charge–the railroad, whose influence created the national park and then built the facilities that defined the look of the park for the next 100 years.

But the long landscaped walkway from the Glacier Park Lodge to the Great Northern passenger station, also themed in Rustic style, let everyone know who was in charge–the railroad, whose influence created the national park and then built the facilities that defined the look of the park for the next 100 years.

Conrad, the seat of Pondera County, is a railroad town, although the town’s close proximity to Interstate I-15 means that so many have forgotten the importance of this Great Northern Railway spur line that stretches from Shelby on the main line south to Great Falls.

Conrad, the seat of Pondera County, is a railroad town, although the town’s close proximity to Interstate I-15 means that so many have forgotten the importance of this Great Northern Railway spur line that stretches from Shelby on the main line south to Great Falls.

The town’s 1920s Arts and Crafts/ Chalet style Great Northern passenger station, along with grain elevators, serve as a reminder of the railroad’s importance to transporting the grains from neighboring ranches.

The town’s 1920s Arts and Crafts/ Chalet style Great Northern passenger station, along with grain elevators, serve as a reminder of the railroad’s importance to transporting the grains from neighboring ranches. Facing the depot is a combination symmetrical town, with one story brick buildings, several of them classic western bars, and then a block long T-plan that connects to the historic federal highway U.S. 87.

Facing the depot is a combination symmetrical town, with one story brick buildings, several of them classic western bars, and then a block long T-plan that connects to the historic federal highway U.S. 87.

U.S. Highway 2 enters northwest Montana in Lincoln County and from there the federal highway stretches eastward through the towns of Troy and Libby with vast rural stretches along the way to Kalispell. Paralleling the highway is the historic route of the Great Northern Railway, which brought timber and mining industries to this corner of Montana.

U.S. Highway 2 enters northwest Montana in Lincoln County and from there the federal highway stretches eastward through the towns of Troy and Libby with vast rural stretches along the way to Kalispell. Paralleling the highway is the historic route of the Great Northern Railway, which brought timber and mining industries to this corner of Montana. Before you encounter the towns, however, there is a spot that is among my favorite in the state, and a place that I discussed in some depth in the book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History: Kootenai Falls.

Before you encounter the towns, however, there is a spot that is among my favorite in the state, and a place that I discussed in some depth in the book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History: Kootenai Falls.

The falls is spectacular, no matter what time of the year you visit. But do stop and consider the mountains and bluffs that surround it. The entire landscape is what mattered to the Native Americans as they navigated through the area, or took vision quests at isolated places, or stopped to fish along the banks or hunt the wild game who also came to the falls for nourishment.

The falls is spectacular, no matter what time of the year you visit. But do stop and consider the mountains and bluffs that surround it. The entire landscape is what mattered to the Native Americans as they navigated through the area, or took vision quests at isolated places, or stopped to fish along the banks or hunt the wild game who also came to the falls for nourishment. There are few less untouched places than Kootenai Falls. The county park provides access and information. It is then up to you to explore, stop, and think about how humans have interacted with this places, taking aways thoughts and messages that we can only guess at, for thousands of years.

There are few less untouched places than Kootenai Falls. The county park provides access and information. It is then up to you to explore, stop, and think about how humans have interacted with this places, taking aways thoughts and messages that we can only guess at, for thousands of years. In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core. The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century. Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks.

Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks. But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed.

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed. Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west. The Clark’s Fork River and transportation through the valleys and over the Rocky Mountains lie at the core of Missoula’s early history. Captain John Mullan blazed his road through here immediately before the Civil War, and a Mullan Road marker is downtown.

The Clark’s Fork River and transportation through the valleys and over the Rocky Mountains lie at the core of Missoula’s early history. Captain John Mullan blazed his road through here immediately before the Civil War, and a Mullan Road marker is downtown. White settlement first arrived in the initial territorial years and a sawmill was the first major business. As a river crossroads town, Missoula grew, and then became a permanent dot on the federal map with the arrival of Fort Missoula, established in 1877. The fort, largely neglected when I conducted my work for the state historic preservation plan in 1984, is now a regional heritage center.

White settlement first arrived in the initial territorial years and a sawmill was the first major business. As a river crossroads town, Missoula grew, and then became a permanent dot on the federal map with the arrival of Fort Missoula, established in 1877. The fort, largely neglected when I conducted my work for the state historic preservation plan in 1984, is now a regional heritage center.

Built in 1901, the Northern Pacific passenger station is an impressive example of Renaissance Revival style, designed by the architectural firm of Reed and Stem, and symbolized the turn of the century dominance of the railroad over the region’s transportation and the importance of Missoula to the railroad as a major train yard. The station, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, stands at the historic “top” of downtown Missoula, which at its bare bones has the classic T-plan of a railroad hub of the late 19th century. The Northern Pacific tracks and related railroad warehouses are the top of the “T” stretching in both directions with Interstate I-90 crossing the river bluffs to the northeast. Two reminders of the historic railroad traffic are adjacent to the station–a steam Northern Pacific engine and a diesel Burlington Northern engine.

Built in 1901, the Northern Pacific passenger station is an impressive example of Renaissance Revival style, designed by the architectural firm of Reed and Stem, and symbolized the turn of the century dominance of the railroad over the region’s transportation and the importance of Missoula to the railroad as a major train yard. The station, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, stands at the historic “top” of downtown Missoula, which at its bare bones has the classic T-plan of a railroad hub of the late 19th century. The Northern Pacific tracks and related railroad warehouses are the top of the “T” stretching in both directions with Interstate I-90 crossing the river bluffs to the northeast. Two reminders of the historic railroad traffic are adjacent to the station–a steam Northern Pacific engine and a diesel Burlington Northern engine.

The Milwaukee was not to be out-done by the Northern Pacific when it arrived in Missoula in 1908. Railroad architect J. J. Lindstrand gave the line a fashionable Misson-style passenger station and offices, which opened in 1910. It too is listed in the National Register. Like the company’s stations in Great Falls and Butte, built approximately at the same time, the station has a tall tower that commanded the city’s early 20th century skyline, and made the depot easy to find. Located dramatically along the Clark’s Fork River, the arrival of the railroad and the construction of the depot led to a new frenzy of building on South Higgins Street, and a good many of those one-story and two-story buildings remain in use today.

The Milwaukee was not to be out-done by the Northern Pacific when it arrived in Missoula in 1908. Railroad architect J. J. Lindstrand gave the line a fashionable Misson-style passenger station and offices, which opened in 1910. It too is listed in the National Register. Like the company’s stations in Great Falls and Butte, built approximately at the same time, the station has a tall tower that commanded the city’s early 20th century skyline, and made the depot easy to find. Located dramatically along the Clark’s Fork River, the arrival of the railroad and the construction of the depot led to a new frenzy of building on South Higgins Street, and a good many of those one-story and two-story buildings remain in use today.

Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area. Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.