Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

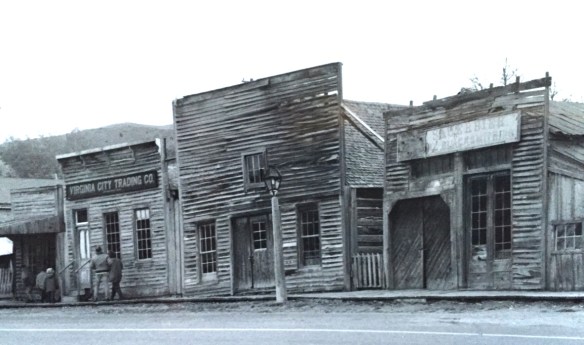

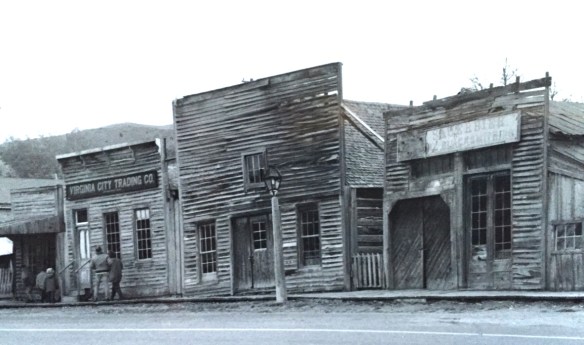

As I discussed in the article, “the Bovey family spent its own money and raised funds to restore Virginia City, then largely abandoned and in decay, to its appearance during the years the town served as a major western mining center and the territorial capital of Montana. Like the Williamsburg restoration, which focused on one key story—the revolution—in its depiction of history, the Virginia City restoration also showcased one dramatic event—the vigilante movement for law and order of the late 1860s. Success at Virginia City led the restoration managers to expand their exhibits to the neighboring “ghost town” of Nevada City, where they combined the few remaining original structures with historic buildings moved from several Montana locations to create a “typical” frontier town.”

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

property and keep both Virginia City and the recreated Nevada City open to the public.” The black and white photos I am sharing here come from a trip in 1990 that I specifically took to record Virginia City as the restored town out of the fear that the place would be dismantled, and this unique experiment in preservation lost.

About ten years ago, I was given the opportunity to return to Virginia City and to see what the public efforts had brought to the town. At that time local and state officials were interested in pursuing heritage area designation. That did not happen but it was a time when I began to understand even larger stories at Virginia City than 20 years earlier.

One of the “new” properties I considered this decade in my exploration of Virginia City was its historic cemetery. Yes, like tens of thousands of others I had been to and given due deference to “Boot Hill,” and its 20th century markers for the vigilante victims

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

There are hand-cut stone grave houses, placed above ground–the burial is actually below the ground, but the houses for mid-19th century Americans symbolized home, family, and the idea that the loved one had “gone home.” The one at the Virginia City Cemetery has a “flat roof” while I am more accustomed to a sharp gable roof on such structures.

The cast-metal prefabricated grave markers, according to early literature on the topic, are “rare.” Compared to masonry markers, yes these Victorian era markers are few in number. But they are not particularly rare; I have found them in rural and small town cemeteries across the South. They are here in Virginia City too.

One of the most prominent belonged to Union Civil War veteran, and Kentucky native, James E. Callaway, who served in the Illinois state legislature after the war, in 1869, but then came to Virginia City and served as secretary to the territorial government from 1871 to 1877. He also was a delegate to both constitutional conventions in the 1880s. He died in Virginia City in 1905.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Another property type I ignored in 1984-85 during my work in Virginia City was the impact of the New Deal. The town has a wonderful WPA-constructed community hall/ gymnasium, which is still used for its original purposes.

The impact of the Montana Heritage Foundation and the concerted state effort beginning in the mid-1990s has been profound on Virginia City. There has been a generation of much needed work of collection management at the curatorial center, shown below. The Boveys not only collected and restored buildings in the mid-20th century, they also packed them with “things”–and many of these are very valuable artifacts of the territorial through early statehood era.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

more than a “quaint, Old West” experience–they can actually learn about the rigors, challenges, and opportunities of the gold rush frontier in the northern Rockies.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

Here in 2016, the preservation community is commemorating the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act. The impact of that federal legislation has been truly significant, and can be found throughout the state. But the earlier efforts by families, local communities, and state governments to save what they could of the past, in some cases to market it as a heritage tourism asset, in other cases, to save it for themselves, must also be commemorated. Virginia City begins the state’s preservation story in many ways–and it will always need our attention.

But in the last 30 years, Polson has boomed as a lakeside resort town, with a population of 4700 today compared to the 2800 of the 1980s. Key landmarks remain but nothing has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since my 1984 visit, even the great New Deal modern courthouse above.

But in the last 30 years, Polson has boomed as a lakeside resort town, with a population of 4700 today compared to the 2800 of the 1980s. Key landmarks remain but nothing has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since my 1984 visit, even the great New Deal modern courthouse above.

These landmarks need to be treasured because a new Polson is emerging all around town–and could crowd out the places that frame the community’s identity. Right now there is a balance between old and new, but a tipping point is around the corner.

These landmarks need to be treasured because a new Polson is emerging all around town–and could crowd out the places that frame the community’s identity. Right now there is a balance between old and new, but a tipping point is around the corner.

Moiese is best known, by far, as the entrance to the National Bison Range, where a general store stands nearby the refuge gate. Created by Congress in 1908, the refuge took

Moiese is best known, by far, as the entrance to the National Bison Range, where a general store stands nearby the refuge gate. Created by Congress in 1908, the refuge took

additional land–almost 19,000 acres- from the tribes, without their consent, to create a safe haven for the remaining bison in the region. A few hundred bison live within its boundaries today. In 2016 the National Park Service began discussions with the Consolidated Kootenai and Salish Tribe to transfer management of the refuge to the tribe.

additional land–almost 19,000 acres- from the tribes, without their consent, to create a safe haven for the remaining bison in the region. A few hundred bison live within its boundaries today. In 2016 the National Park Service began discussions with the Consolidated Kootenai and Salish Tribe to transfer management of the refuge to the tribe. Eight miles north of Moiese along the railroad line is the town of Charlo, named in honor of Chief Charlo of the Bitterroot Salish, who was forced from the Bitterroot Valley to move to the reservation in 1891. Charlo served as head chief of the Bitterroot Salish from 1870-

Eight miles north of Moiese along the railroad line is the town of Charlo, named in honor of Chief Charlo of the Bitterroot Salish, who was forced from the Bitterroot Valley to move to the reservation in 1891. Charlo served as head chief of the Bitterroot Salish from 1870- 1910. As a railroad town, Charlo is like many along the Northern Pacific, with a brief strip of businesses facing the railroad tracks, marked by the town’s sole grain elevator. It has a classic rural bar, Tiny’s Tavern, with its brightly painted exterior of concrete block, with brick accents. Built in 1946 by Tiny Browne, it was both a motel and a tavern, and a local museum of items that Tiny thought were interesting. Browne died in 1977 and his sister, Celeste Fagan, next owned the tavern, managed by Edna Easterly who recalled in a story in the Missoulian of April 20, 2007 that Tiny “was known as the bank of Charlo. Tiny always carried a lot of money in his pocket and if you needed to cash a check, you went to Tiny.”

1910. As a railroad town, Charlo is like many along the Northern Pacific, with a brief strip of businesses facing the railroad tracks, marked by the town’s sole grain elevator. It has a classic rural bar, Tiny’s Tavern, with its brightly painted exterior of concrete block, with brick accents. Built in 1946 by Tiny Browne, it was both a motel and a tavern, and a local museum of items that Tiny thought were interesting. Browne died in 1977 and his sister, Celeste Fagan, next owned the tavern, managed by Edna Easterly who recalled in a story in the Missoulian of April 20, 2007 that Tiny “was known as the bank of Charlo. Tiny always carried a lot of money in his pocket and if you needed to cash a check, you went to Tiny.” Most important for its architecture, however, is the town’s public school, a wonderful example of Art Deco style from the New Deal decade of the 1930s.

Most important for its architecture, however, is the town’s public school, a wonderful example of Art Deco style from the New Deal decade of the 1930s. Ronan is a third town along the railroad corridor, named for a former white superintendent of the reservation. The town’s demographics today are mostly white, with a little more than a quarter Native American population. Ronan proudly proclaims its existence not only with a gate sign, connecting the business district to the sprawl along U.S. Highway 93 but also a log visitor center and interpretive park on the highway.

Ronan is a third town along the railroad corridor, named for a former white superintendent of the reservation. The town’s demographics today are mostly white, with a little more than a quarter Native American population. Ronan proudly proclaims its existence not only with a gate sign, connecting the business district to the sprawl along U.S. Highway 93 but also a log visitor center and interpretive park on the highway.

The facade expresses a confident future, which is needed in today’s uncertain economic climate for rural hospitals across the state. But my favorite building in Ronan speaks to my love for adaptive reuse and mid-20th century modern design. The town library is an

The facade expresses a confident future, which is needed in today’s uncertain economic climate for rural hospitals across the state. But my favorite building in Ronan speaks to my love for adaptive reuse and mid-20th century modern design. The town library is an exquisite example of mid-century modern, and was once a local bank before being converted into the library.

exquisite example of mid-century modern, and was once a local bank before being converted into the library.

Sanders County, like many of the places that are on the western side of the Rocky Mountains, has boomed in the last 25 years, from a population over 8,000 to the current estimated population of 11,300. It is close to Missoula, the eastern side is not far from Flathead Lake, Montana Highway 200 runs from Dixon to the end of the county at Heron. With wide valleys and narrow gorges created by both the Flathead and Clark’s Fork Rivers, which meet outside the town of Paradise, Sanders County is frankly a spectacular landscape, with dramatic mountain views framing open plains, such as the image above and the awesome gorge of Clark’s Fork River, below at Thompson Falls.

Sanders County, like many of the places that are on the western side of the Rocky Mountains, has boomed in the last 25 years, from a population over 8,000 to the current estimated population of 11,300. It is close to Missoula, the eastern side is not far from Flathead Lake, Montana Highway 200 runs from Dixon to the end of the county at Heron. With wide valleys and narrow gorges created by both the Flathead and Clark’s Fork Rivers, which meet outside the town of Paradise, Sanders County is frankly a spectacular landscape, with dramatic mountain views framing open plains, such as the image above and the awesome gorge of Clark’s Fork River, below at Thompson Falls. The eastern side of the county is just as dramatic just in a far different way. For centuries First Peoples hunted game and dug the camas root in the broad upland prairie that became known as Camas Prairie, crossed now by Montana Highway 28.

The eastern side of the county is just as dramatic just in a far different way. For centuries First Peoples hunted game and dug the camas root in the broad upland prairie that became known as Camas Prairie, crossed now by Montana Highway 28. Then, leading from the county’s southeastern edge there is the beautiful Flathead River Valley, followed by Montana Highway 200, from Dixon to Paradise, and most importantly,

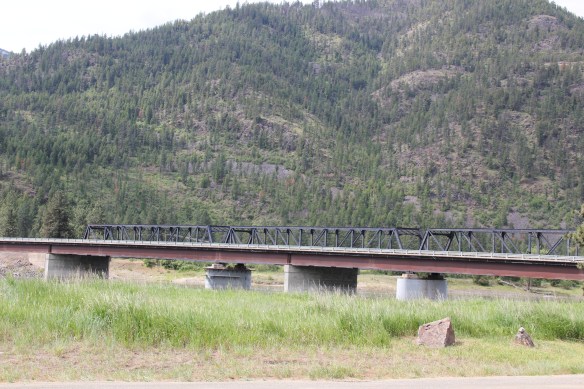

Then, leading from the county’s southeastern edge there is the beautiful Flathead River Valley, followed by Montana Highway 200, from Dixon to Paradise, and most importantly, a transportation route initially carved as a trail by the First Peoples who became the nucleus of today’s Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe and much later engineered into a major corridor by the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, as it stretched westward from Missoula to the west coast.

a transportation route initially carved as a trail by the First Peoples who became the nucleus of today’s Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe and much later engineered into a major corridor by the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, as it stretched westward from Missoula to the west coast. In its wake, the Northern Pacific created most of the county’s townsites by locating sidings along the track. Substantial settlement arrived once the federal government opened lands for the homesteading boom in the early 20th century.

In its wake, the Northern Pacific created most of the county’s townsites by locating sidings along the track. Substantial settlement arrived once the federal government opened lands for the homesteading boom in the early 20th century. Dixon, named for the former Montana governor Joseph Dixon, is one of the remaining railroad/homesteading towns along the Flathead River. The fate of the community bar, above, is symbolic of the recent history of the town, one of population decline.

Dixon, named for the former Montana governor Joseph Dixon, is one of the remaining railroad/homesteading towns along the Flathead River. The fate of the community bar, above, is symbolic of the recent history of the town, one of population decline.

Local residents are being excellent stewards of this captivating property–certainly one of my favorite spots in the state combining landscape with architecture with history. The architect was the Missoula designer H. E. Kirkemo, and the school was completed in 1940, near the end of the New Deal school building programs.

Local residents are being excellent stewards of this captivating property–certainly one of my favorite spots in the state combining landscape with architecture with history. The architect was the Missoula designer H. E. Kirkemo, and the school was completed in 1940, near the end of the New Deal school building programs.

The school had just closed its doors for good when I lasted visited but the restoration planning has been underway ever since. I look forward to my next visit to Paradise to experience the final results. Near the school is another historic community property, the Paradise Cemetery, where tombstones mark the names of those who worked so long for the railroad and for the creation of this place within the Clark’s Fork River Valley.

The school had just closed its doors for good when I lasted visited but the restoration planning has been underway ever since. I look forward to my next visit to Paradise to experience the final results. Near the school is another historic community property, the Paradise Cemetery, where tombstones mark the names of those who worked so long for the railroad and for the creation of this place within the Clark’s Fork River Valley.

Montana Highway 141 cuts north from Avon On U. S. Highway 12 to halfway between the towns of Ovando and Lincoln on Montana Highway 200. Its is high mountains prairie travel at its best, although the height of ranching along this route disappeared a while back. About 12-13 miles north of Avon you cross into the Nevada Creek drainage, which has long watered the land, enhanced after the New Deal added the Nevada Creek earthen dam that created Nevada Creek Reservoir in 1938.

Montana Highway 141 cuts north from Avon On U. S. Highway 12 to halfway between the towns of Ovando and Lincoln on Montana Highway 200. Its is high mountains prairie travel at its best, although the height of ranching along this route disappeared a while back. About 12-13 miles north of Avon you cross into the Nevada Creek drainage, which has long watered the land, enhanced after the New Deal added the Nevada Creek earthen dam that created Nevada Creek Reservoir in 1938.

Along the east banks of the lake are remnants of the Fitzpatrick Ranch, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I highlighted the property in my book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986). Jimmy Isbel established the property in 1872,

Along the east banks of the lake are remnants of the Fitzpatrick Ranch, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I highlighted the property in my book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986). Jimmy Isbel established the property in 1872,

Thirty years ago, this significant collection of vernacular buildings was in good condition, but the years since have been hard on the property, and the complex now needs serious preservation attention. The loss of the roof on the log barn, and the general poor condition of the roofs of the outbuildings are major concerns.

Thirty years ago, this significant collection of vernacular buildings was in good condition, but the years since have been hard on the property, and the complex now needs serious preservation attention. The loss of the roof on the log barn, and the general poor condition of the roofs of the outbuildings are major concerns.

Between the Fitzpatrick Ranch and Helmville is the Barger Ranch, also from the late 19th century judging from the more polished example of Queen Anne style in the ranch house. It is living proof that not all of the Nevada Creek ranches have passed away. The Nevada Creek Water Users Association at Helmville still operates to distribute the invaluable water from the reservoir.

Between the Fitzpatrick Ranch and Helmville is the Barger Ranch, also from the late 19th century judging from the more polished example of Queen Anne style in the ranch house. It is living proof that not all of the Nevada Creek ranches have passed away. The Nevada Creek Water Users Association at Helmville still operates to distribute the invaluable water from the reservoir.  Helmville was another topic in my 1986 book. Throughout the Nevada Creek drainage, you could help but be impressed with the log construction, and the various types of notching used for the buildings. Helmville had a particular interesting grouping of wood frame and log buildings, which were highlighted by a 1984 photograph in the book. That exact view could not be replicated 30 years later but several of the old buildings still stood.

Helmville was another topic in my 1986 book. Throughout the Nevada Creek drainage, you could help but be impressed with the log construction, and the various types of notching used for the buildings. Helmville had a particular interesting grouping of wood frame and log buildings, which were highlighted by a 1984 photograph in the book. That exact view could not be replicated 30 years later but several of the old buildings still stood.

Helmville has a good bit of continuity. Along with the row of buildings on Montana 271 there is a turn of the 20th century gable-front cottage and a two-story lodge building that has been turned into a garage.

Helmville has a good bit of continuity. Along with the row of buildings on Montana 271 there is a turn of the 20th century gable-front cottage and a two-story lodge building that has been turned into a garage.

Trixie’s was the same fun dive that I always recalled, but the village’s historic buildings had been restored, looking good. Business appeared to be brisk. A new community church has been opened, and a major interpretive place for the “Lewis Minus Clark” expedition had been installed. Kudos to both the U.S. Forest Service and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail for allowing a bit of humor in this marker.

Trixie’s was the same fun dive that I always recalled, but the village’s historic buildings had been restored, looking good. Business appeared to be brisk. A new community church has been opened, and a major interpretive place for the “Lewis Minus Clark” expedition had been installed. Kudos to both the U.S. Forest Service and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail for allowing a bit of humor in this marker.

The school had also expanded from its New Deal core of the 1930s, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration. But the most noticeable change was the town’s street signs–first the fact that a small place had street signs but then the nostalgic backpacker theme of these cast iron marvels.

The school had also expanded from its New Deal core of the 1930s, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration. But the most noticeable change was the town’s street signs–first the fact that a small place had street signs but then the nostalgic backpacker theme of these cast iron marvels. Ovando is a good location on the Blackfoot River for sportsmen, anglers, and hikers headed into the Bob Marshall Wilderness–its recent change demonstrates the influence on those groups on the 21st century Montana landscape.

Ovando is a good location on the Blackfoot River for sportsmen, anglers, and hikers headed into the Bob Marshall Wilderness–its recent change demonstrates the influence on those groups on the 21st century Montana landscape.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters. The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory.

The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory. The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century.

The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century. Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history. Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses.

Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses. In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Imagine my pleasure to be there for the theatre’s grand opening May 19, 2012. Not only had the community raised the funds to repair and reopen the business, they also took great pains to restore it to its earlier architectural glory. Such an achievement for a town of just over 3,000 residents–when you consider that the next city south on Interstate I-90 is Anaconda with its monument Washoe Theatre, I immediately began to think of future “movie palace” trips. What a treat, both for the experience and architecture.

Imagine my pleasure to be there for the theatre’s grand opening May 19, 2012. Not only had the community raised the funds to repair and reopen the business, they also took great pains to restore it to its earlier architectural glory. Such an achievement for a town of just over 3,000 residents–when you consider that the next city south on Interstate I-90 is Anaconda with its monument Washoe Theatre, I immediately began to think of future “movie palace” trips. What a treat, both for the experience and architecture.

In that same trip to Deer Lodge, I noted how the community had recently enhanced the National Register-listed W. K. Kohrs Memorial Library (1902), one of the region’s great Classical Revival buildings by the Butte architectural firm of Link and Carter (J.G. Link would soon become one of the state’s most renowned classicists), by expanding the library

In that same trip to Deer Lodge, I noted how the community had recently enhanced the National Register-listed W. K. Kohrs Memorial Library (1902), one of the region’s great Classical Revival buildings by the Butte architectural firm of Link and Carter (J.G. Link would soon become one of the state’s most renowned classicists), by expanding the library with an addition to the side and behind the commanding entrance portico. Although it has proven to be difficult for such a small town to keep the library professionally staffed, the care they have shown the exterior and interior indicate they understand the value of this monument from the past.

with an addition to the side and behind the commanding entrance portico. Although it has proven to be difficult for such a small town to keep the library professionally staffed, the care they have shown the exterior and interior indicate they understand the value of this monument from the past.

Then add in the impressive examples of turn of the 20th century church architecture, represented by the Cotswold Gothic stone work of St. James Episcopal Church, the more former Tudor Revival of the 1st Presbyterian Church, and the more vernacular yet

Then add in the impressive examples of turn of the 20th century church architecture, represented by the Cotswold Gothic stone work of St. James Episcopal Church, the more former Tudor Revival of the 1st Presbyterian Church, and the more vernacular yet

contemporary styling of the Ravalli County Bank or the “new” county courthouse of 1976, a building that I totally dismissed in 1984 but now that it has reached the 40 year mark the design seems so much of its time, and a very interesting local reaction by the firm of Howland and Associates to the ne0-Colonial Revival that gripped so much of the nation during the American bicentennial.

contemporary styling of the Ravalli County Bank or the “new” county courthouse of 1976, a building that I totally dismissed in 1984 but now that it has reached the 40 year mark the design seems so much of its time, and a very interesting local reaction by the firm of Howland and Associates to the ne0-Colonial Revival that gripped so much of the nation during the American bicentennial.

Adaptive reuse had put some buildings back into use, such as the historic Creamery, once such an important link between town and ranch in the county. Other landmarks didn’t

Adaptive reuse had put some buildings back into use, such as the historic Creamery, once such an important link between town and ranch in the county. Other landmarks didn’t

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school. While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students.

While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students. Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.