Kalispell’s Main Street–the stem of the T-plan that dates to the town’s very beginning as a stop on the Great Northern Railway–has a different mix of businesses today than 30 years ago when I visited during my state historic preservation plan survey. It also now is a historic district within National Register of Historic Places, noted for its mix of one-story and two-story Western Commercial style businesses along with large historic hotels and an opera house for entertainment.

Kalispell’s Main Street–the stem of the T-plan that dates to the town’s very beginning as a stop on the Great Northern Railway–has a different mix of businesses today than 30 years ago when I visited during my state historic preservation plan survey. It also now is a historic district within National Register of Historic Places, noted for its mix of one-story and two-story Western Commercial style businesses along with large historic hotels and an opera house for entertainment.

The Opera House, and I’m sorry you have to love the horse and buggy sign added to the front some years ago, dates to 1896 as the dream of merchant John MacIntosh to give the fledging community everything it needed. On the first floor was his store, which over the years sold all sorts of items, from thimbles to Studebakers. The second floor was a community space, for meetings, a gymnasium, and even from a brief period from 1905 to 1906 a skating rink. In this way, MacIntosh followed the ten-year-old model of a much larger building in a much larger city, the famous Auditorium Building in Chicago, providing Kalispell with a major indoor recreation space and landmark. Allegedly over 1000 people attended a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon after the opening.

The Opera House, and I’m sorry you have to love the horse and buggy sign added to the front some years ago, dates to 1896 as the dream of merchant John MacIntosh to give the fledging community everything it needed. On the first floor was his store, which over the years sold all sorts of items, from thimbles to Studebakers. The second floor was a community space, for meetings, a gymnasium, and even from a brief period from 1905 to 1906 a skating rink. In this way, MacIntosh followed the ten-year-old model of a much larger building in a much larger city, the famous Auditorium Building in Chicago, providing Kalispell with a major indoor recreation space and landmark. Allegedly over 1000 people attended a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon after the opening.

Another highlight of the historic is the Kalispell Grand Hotel (1912), designed by local architect Marion Riffo and constructed by B. B. Gilliland, a local builder. Designed not only as a railroad hotel for traveling “drummers,” it also served as a first stop for homesteaders flooding into the region in that decade. Montana writer Frank B. Linderman was the hotel manager from 1924 to 1926, and his friend western artist Charles M Russell visited and stayed at the hotel in those years. This place, frankly, was a dump when I surveyed Kalispell in 1984-1985 but five years later a restoration gave the place back its dignity and restored its downtown landmark status.

The Alpine Lighting Center dates to 1929 when local architect Fred Brinkman designed the store for Montgomery Ward, the famous Chicago-based catalog merchant. Its eye-catching facade distinguished it from many of the other more unadorned two-part commercial blocks on Main Street.

The Alpine Lighting Center dates to 1929 when local architect Fred Brinkman designed the store for Montgomery Ward, the famous Chicago-based catalog merchant. Its eye-catching facade distinguished it from many of the other more unadorned two-part commercial blocks on Main Street.

My favorite Main Street building is probably the cast-iron, tin facade over a two-story brick building that now houses an antique store. It was once the Brewery Saloon (c. 1892). This is a classic “Western Commercial” look and can be found in several Montana towns.

Main Street defines the heart of the business district. Along side streets are other, more modern landmarks. Let me emphasize just a few favorites, starting with the outstanding contemporary design of the Sutherland Cleaners building, located on 2nd Street, the epitome of mid-20th century Montana modernism. It is such an expressive building but of course in 1984 it was “too recent” for me to even note its existence.

At least I had enough good sense to note the existence of its neighbor, the Art Deco-styled Strand Theater (1927). I enjoyed a movie there in 1984–and the theater kept showing movies until 2007.

The preservation of the Strand Theater, and the other downtown historic theater building, the Classical Revival-styled Liberty Theater (1920-21) by Kalispell architect Marion Riffo, is the work of the Fresh Life Church, which owns and uses both buildings to serve its congregation and the community.

Another modernist favorite is a Fred Brinkmann-inspired design, the flamboyant Art Deco of the historic City Garage (1931), now home to local television station.

On the other side of Main Street is another building that evokes 1930s interpretation of Art Deco, the Eagles Lodge Building, a reminder of the key role played in fraternal lodges in developing towns and cities in early Montana.

Let’s close this look at Kalispell’s commercial architecture with the Kalispell Mercantile Building (1892-1910), which was established by the regional retail powerhouse, the Missoula Mercantile, at the very beginning of the city’s existence. Kalispell has figured out what Missoula refuses to do–that a building such as this is worthy of preservation, and if maintained properly, can continue to serve the town’s economy for decades more.

The town’s early religious institutions also built to stay, leaving key landmarks throughout the neighborhoods that serve as historic anchors today. On Main Street alone there is the unique Arts and Crafts styled First Presbyterian Church (1925-26) by architect Fred Brinkman, and the Gothic Revival masonry and tower of Bethlehem Lutheran Church (1932-1937).

The town’s early religious institutions also built to stay, leaving key landmarks throughout the neighborhoods that serve as historic anchors today. On Main Street alone there is the unique Arts and Crafts styled First Presbyterian Church (1925-26) by architect Fred Brinkman, and the Gothic Revival masonry and tower of Bethlehem Lutheran Church (1932-1937).

The city’s first Catholic school dated to 1917. The historic St. Matthew’s Catholic Church (1910) by Great Falls architect George Shanley remains the city’s most commanding Gothic landmark.

The city’s first Catholic school dated to 1917. The historic St. Matthew’s Catholic Church (1910) by Great Falls architect George Shanley remains the city’s most commanding Gothic landmark.

As I would come to find out, on two return trips here in 1984, the town was much more than that, it was a true bordertown between two nations and two cultures. The two trips came about from, first, a question about a public building’s eligibility for the National Register, and, second, the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, where such obvious landmarks as the National Hotel and Eureka passenger depot were noted. Thirty

As I would come to find out, on two return trips here in 1984, the town was much more than that, it was a true bordertown between two nations and two cultures. The two trips came about from, first, a question about a public building’s eligibility for the National Register, and, second, the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan, where such obvious landmarks as the National Hotel and Eureka passenger depot were noted. Thirty

years later I was pleased to see the National Hotel in much better condition but dismayed to see the Great Northern passenger station–a classic example of its early 20th century standardized designs–is far worse condition that it had been in 1984.

years later I was pleased to see the National Hotel in much better condition but dismayed to see the Great Northern passenger station–a classic example of its early 20th century standardized designs–is far worse condition that it had been in 1984. Otherwise, Eureka has done an impressive job of holding together its historic core of downtown one and two-story commercial buildings. In 1995, owners had the Farmers and Merchants State Bank, built in 1907, placed in the National Register. Walking the town, however, you see the potential of a historic district of this turn of the 20th century place.

Otherwise, Eureka has done an impressive job of holding together its historic core of downtown one and two-story commercial buildings. In 1995, owners had the Farmers and Merchants State Bank, built in 1907, placed in the National Register. Walking the town, however, you see the potential of a historic district of this turn of the 20th century place.

Located on a hill perched over the town, the building was obviously a landmark–but in 1984 it also was just 42 years old, and that meant it needed to have exceptional significance to the local community to merit listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Eureka had been a logging community, and the depression hit hard. The new building not only reflected community pride but also local craftsmanship, and it became a

Located on a hill perched over the town, the building was obviously a landmark–but in 1984 it also was just 42 years old, and that meant it needed to have exceptional significance to the local community to merit listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Eureka had been a logging community, and the depression hit hard. The new building not only reflected community pride but also local craftsmanship, and it became a foundation for community resurgence in the decades to come. The building was listed in 1985, and was the first to have my name attached to it, working with Sally Steward of the local historical society. But credit has to go to Pat Bick and especially Marcella Sherfy of the State Historic Preservation Office for urging me to take it on, and to guide me through the maze of the National Register process. Today, it has experienced an adaptive reuse and serves as a rustic log furniture store.

foundation for community resurgence in the decades to come. The building was listed in 1985, and was the first to have my name attached to it, working with Sally Steward of the local historical society. But credit has to go to Pat Bick and especially Marcella Sherfy of the State Historic Preservation Office for urging me to take it on, and to guide me through the maze of the National Register process. Today, it has experienced an adaptive reuse and serves as a rustic log furniture store. During those visits in 1984 I also held a public meeting in Eureka for the state historic preservation plan, where I learned about the Tobacco Valley Historical Society and its efforts to preserve buildings destined for the chopping block through its museum village on the southern edge of town. Here the community gathered the Great Northern depot (1903) of Rexford, the same town’s 1926 Catholic Church, the Mt. Roberts lookout tower, the Fewkes Store, and a U.S. Forest Service big Creek Cabin from 1926.

During those visits in 1984 I also held a public meeting in Eureka for the state historic preservation plan, where I learned about the Tobacco Valley Historical Society and its efforts to preserve buildings destined for the chopping block through its museum village on the southern edge of town. Here the community gathered the Great Northern depot (1903) of Rexford, the same town’s 1926 Catholic Church, the Mt. Roberts lookout tower, the Fewkes Store, and a U.S. Forest Service big Creek Cabin from 1926.

Libby is the seat of Lincoln County, a typical railroad town along the historic Great Northern Railway corridor. The image above is from the town’s railroad depot, the symbolic beginning of town, from which runs a long main street of businesses, reflecting the T-plan town design, where the long railroad corridor defines the top of the T and the main street forms the stem of the T.

Libby is the seat of Lincoln County, a typical railroad town along the historic Great Northern Railway corridor. The image above is from the town’s railroad depot, the symbolic beginning of town, from which runs a long main street of businesses, reflecting the T-plan town design, where the long railroad corridor defines the top of the T and the main street forms the stem of the T.

courthouse received a totally new front, in a contemporary style, in the 1970s as the town and county expanded in the wake of the federal spending in constructing Libby Dam. The rectangular blockiness, flat roof, and band of windows set within a symmetrical facade makes the courthouse one of the state’s best designs for a rural public building in the late 20th century.

courthouse received a totally new front, in a contemporary style, in the 1970s as the town and county expanded in the wake of the federal spending in constructing Libby Dam. The rectangular blockiness, flat roof, and band of windows set within a symmetrical facade makes the courthouse one of the state’s best designs for a rural public building in the late 20th century. I liked all of those things about Libby in 1984. Imagine my shock and disappointment to learn, as everyone else did, that Libby was one of the poisoned places in the west. In 1919, vermiculite, a natural material that contains asbestos, had been discovered outside of town, and the mines were still operating, producing 80 percent of the vermiculite in the world, under the control of the W.R. Grace company. Residue from the mines had been used in local yards and buildings for decades, a fact that was not known when I visited the town for the state historic preservation plan. When the discovery of the danger became public, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency entered into the fray in 1999, it was already too late for many residents. A federal Superfund project began, and did not conclude its work until 2015, spending some $425 million. Then in 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency announced a public health emergency, spending another $130 million to help residents and to leave a new health infrastructure in place. In a generation, Libby had been turned inside out. EPA announced in 2016 that the cleanup would continue to 2018, and that the project was the longest in the agency’s history.

I liked all of those things about Libby in 1984. Imagine my shock and disappointment to learn, as everyone else did, that Libby was one of the poisoned places in the west. In 1919, vermiculite, a natural material that contains asbestos, had been discovered outside of town, and the mines were still operating, producing 80 percent of the vermiculite in the world, under the control of the W.R. Grace company. Residue from the mines had been used in local yards and buildings for decades, a fact that was not known when I visited the town for the state historic preservation plan. When the discovery of the danger became public, and the federal Environmental Protection Agency entered into the fray in 1999, it was already too late for many residents. A federal Superfund project began, and did not conclude its work until 2015, spending some $425 million. Then in 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency announced a public health emergency, spending another $130 million to help residents and to leave a new health infrastructure in place. In a generation, Libby had been turned inside out. EPA announced in 2016 that the cleanup would continue to 2018, and that the project was the longest in the agency’s history.

Despite the disaster, I saw many signs that Libby residents were determined to remain and rebuild their community. One of the most powerful examples is the conversion of one of the town’s historic schools into a new community arts center as well as school administration offices.

Despite the disaster, I saw many signs that Libby residents were determined to remain and rebuild their community. One of the most powerful examples is the conversion of one of the town’s historic schools into a new community arts center as well as school administration offices.

The asbestos crisis was a terrible disaster for Libby–yet residents refused to let it define their future. There are past accomplishments to acknowledge, an active railroad depot to cherish, a beautiful river and lake, the mountains all around, as celebrated in this public art mural on a downtown building. This place is here to stay, and the historic built environment is a large part of it.

The asbestos crisis was a terrible disaster for Libby–yet residents refused to let it define their future. There are past accomplishments to acknowledge, an active railroad depot to cherish, a beautiful river and lake, the mountains all around, as celebrated in this public art mural on a downtown building. This place is here to stay, and the historic built environment is a large part of it.

The dam is 422 feet tall and stretches across the river for 3,055 feet–well over a 1/2 mile. It creates a huge reservoir, extending 90 miles to the north and into British Columbia, among the ten largest reservoirs in the nation. And like that, a historic river valley became a recreational lake in a joint project between the United States and Canada.

The dam is 422 feet tall and stretches across the river for 3,055 feet–well over a 1/2 mile. It creates a huge reservoir, extending 90 miles to the north and into British Columbia, among the ten largest reservoirs in the nation. And like that, a historic river valley became a recreational lake in a joint project between the United States and Canada.

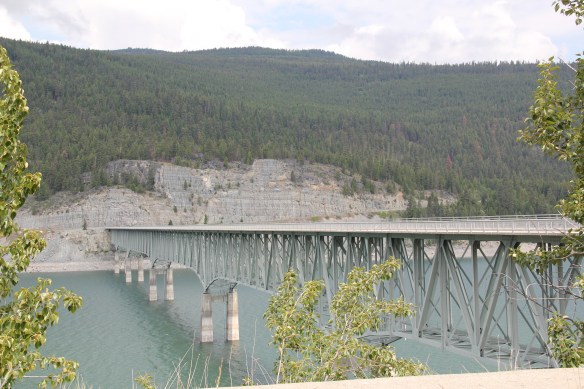

The Lake Koocanusa Bridge, which provides access to a Mennonite community and a backroad way to Yaak, is the state’s longest, and in many ways, its most spectacular multi-truss bridge. The bridge is 2,437 feet long, and stands, depending on water level, some 270 feet above the lake.

The Lake Koocanusa Bridge, which provides access to a Mennonite community and a backroad way to Yaak, is the state’s longest, and in many ways, its most spectacular multi-truss bridge. The bridge is 2,437 feet long, and stands, depending on water level, some 270 feet above the lake.

There was no interpretation at this bridge in 1984, but the scenic highway designation has led to the placement of overlooks and interpretive markers at some places along the lake. One wishes for the same at the Montana town that the lake displaced, Rexford. This once

There was no interpretation at this bridge in 1984, but the scenic highway designation has led to the placement of overlooks and interpretive markers at some places along the lake. One wishes for the same at the Montana town that the lake displaced, Rexford. This once small river town had to move, or be inundated. And since the move took place in the mid to late 1960s, the town embodies the mid-century modern aesthetic, both in the design of many buildings but also in the town plan itself as the federal government finished relocating Rexford in the early 1970s.

small river town had to move, or be inundated. And since the move took place in the mid to late 1960s, the town embodies the mid-century modern aesthetic, both in the design of many buildings but also in the town plan itself as the federal government finished relocating Rexford in the early 1970s.

school by itself is a fascinating statement of both design but also a community’s determination to stay, no matter what the federal government threw their way. Needless to say, in 1984 I paid Rexford no attention–nothing historic was there, it was all new. But now it is clear what a important place in Lincoln County’s 20th century history Rexford came to be.

school by itself is a fascinating statement of both design but also a community’s determination to stay, no matter what the federal government threw their way. Needless to say, in 1984 I paid Rexford no attention–nothing historic was there, it was all new. But now it is clear what a important place in Lincoln County’s 20th century history Rexford came to be.

But in the last 30 years, Polson has boomed as a lakeside resort town, with a population of 4700 today compared to the 2800 of the 1980s. Key landmarks remain but nothing has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since my 1984 visit, even the great New Deal modern courthouse above.

But in the last 30 years, Polson has boomed as a lakeside resort town, with a population of 4700 today compared to the 2800 of the 1980s. Key landmarks remain but nothing has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since my 1984 visit, even the great New Deal modern courthouse above.

These landmarks need to be treasured because a new Polson is emerging all around town–and could crowd out the places that frame the community’s identity. Right now there is a balance between old and new, but a tipping point is around the corner.

These landmarks need to be treasured because a new Polson is emerging all around town–and could crowd out the places that frame the community’s identity. Right now there is a balance between old and new, but a tipping point is around the corner.

Moiese is best known, by far, as the entrance to the National Bison Range, where a general store stands nearby the refuge gate. Created by Congress in 1908, the refuge took

Moiese is best known, by far, as the entrance to the National Bison Range, where a general store stands nearby the refuge gate. Created by Congress in 1908, the refuge took

additional land–almost 19,000 acres- from the tribes, without their consent, to create a safe haven for the remaining bison in the region. A few hundred bison live within its boundaries today. In 2016 the National Park Service began discussions with the Consolidated Kootenai and Salish Tribe to transfer management of the refuge to the tribe.

additional land–almost 19,000 acres- from the tribes, without their consent, to create a safe haven for the remaining bison in the region. A few hundred bison live within its boundaries today. In 2016 the National Park Service began discussions with the Consolidated Kootenai and Salish Tribe to transfer management of the refuge to the tribe. Eight miles north of Moiese along the railroad line is the town of Charlo, named in honor of Chief Charlo of the Bitterroot Salish, who was forced from the Bitterroot Valley to move to the reservation in 1891. Charlo served as head chief of the Bitterroot Salish from 1870-

Eight miles north of Moiese along the railroad line is the town of Charlo, named in honor of Chief Charlo of the Bitterroot Salish, who was forced from the Bitterroot Valley to move to the reservation in 1891. Charlo served as head chief of the Bitterroot Salish from 1870- 1910. As a railroad town, Charlo is like many along the Northern Pacific, with a brief strip of businesses facing the railroad tracks, marked by the town’s sole grain elevator. It has a classic rural bar, Tiny’s Tavern, with its brightly painted exterior of concrete block, with brick accents. Built in 1946 by Tiny Browne, it was both a motel and a tavern, and a local museum of items that Tiny thought were interesting. Browne died in 1977 and his sister, Celeste Fagan, next owned the tavern, managed by Edna Easterly who recalled in a story in the Missoulian of April 20, 2007 that Tiny “was known as the bank of Charlo. Tiny always carried a lot of money in his pocket and if you needed to cash a check, you went to Tiny.”

1910. As a railroad town, Charlo is like many along the Northern Pacific, with a brief strip of businesses facing the railroad tracks, marked by the town’s sole grain elevator. It has a classic rural bar, Tiny’s Tavern, with its brightly painted exterior of concrete block, with brick accents. Built in 1946 by Tiny Browne, it was both a motel and a tavern, and a local museum of items that Tiny thought were interesting. Browne died in 1977 and his sister, Celeste Fagan, next owned the tavern, managed by Edna Easterly who recalled in a story in the Missoulian of April 20, 2007 that Tiny “was known as the bank of Charlo. Tiny always carried a lot of money in his pocket and if you needed to cash a check, you went to Tiny.” Most important for its architecture, however, is the town’s public school, a wonderful example of Art Deco style from the New Deal decade of the 1930s.

Most important for its architecture, however, is the town’s public school, a wonderful example of Art Deco style from the New Deal decade of the 1930s. Ronan is a third town along the railroad corridor, named for a former white superintendent of the reservation. The town’s demographics today are mostly white, with a little more than a quarter Native American population. Ronan proudly proclaims its existence not only with a gate sign, connecting the business district to the sprawl along U.S. Highway 93 but also a log visitor center and interpretive park on the highway.

Ronan is a third town along the railroad corridor, named for a former white superintendent of the reservation. The town’s demographics today are mostly white, with a little more than a quarter Native American population. Ronan proudly proclaims its existence not only with a gate sign, connecting the business district to the sprawl along U.S. Highway 93 but also a log visitor center and interpretive park on the highway.

The facade expresses a confident future, which is needed in today’s uncertain economic climate for rural hospitals across the state. But my favorite building in Ronan speaks to my love for adaptive reuse and mid-20th century modern design. The town library is an

The facade expresses a confident future, which is needed in today’s uncertain economic climate for rural hospitals across the state. But my favorite building in Ronan speaks to my love for adaptive reuse and mid-20th century modern design. The town library is an exquisite example of mid-century modern, and was once a local bank before being converted into the library.

exquisite example of mid-century modern, and was once a local bank before being converted into the library.

Hot Springs, off from Montana Highway 28 on the eastern edge of Sanders County, was a place that received little attention in the survey work of 1984-1985. Everyone knew it was there, and that hot springs had been in operation trying to lure automobile travelers since the 1920s–but at that time, that was too new. The focus was elsewhere, especially on the late 19th century resorts like Chico Hot Springs (believe or not, Chico was not on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984). This section of what is now the reservation of the Consolidated Salish and Kootenai Tribes was opened to homesteaders in 1910 and first settlement came soon thereafter. The development of the hot springs as an attraction began within a generation.

Hot Springs, off from Montana Highway 28 on the eastern edge of Sanders County, was a place that received little attention in the survey work of 1984-1985. Everyone knew it was there, and that hot springs had been in operation trying to lure automobile travelers since the 1920s–but at that time, that was too new. The focus was elsewhere, especially on the late 19th century resorts like Chico Hot Springs (believe or not, Chico was not on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984). This section of what is now the reservation of the Consolidated Salish and Kootenai Tribes was opened to homesteaders in 1910 and first settlement came soon thereafter. The development of the hot springs as an attraction began within a generation. Due to the 21st century fascination from historic preservationists for the modern movement of the mid-20th century, however, Hot Springs is now squarely on the map as a fascinating example of a tourist destination at the height of the automobile age from the 1930s to 1960s.

Due to the 21st century fascination from historic preservationists for the modern movement of the mid-20th century, however, Hot Springs is now squarely on the map as a fascinating example of a tourist destination at the height of the automobile age from the 1930s to 1960s.

Not everything fit into this mold, naturally. There remains a representative set of gable-front shotgun-form “cabins” that housed visitors staying for several days and various one-story buildings served both visitors and year-round residents.

Not everything fit into this mold, naturally. There remains a representative set of gable-front shotgun-form “cabins” that housed visitors staying for several days and various one-story buildings served both visitors and year-round residents.

The loss would be significant because few mid-20th century buildings in Montana, especially rural Montana, are so expressive of the modernist ethos, with the flat roofs, the long, low wings and the prominent chimney as a design element. Then there are the round steel stilts on which the building rests.

The loss would be significant because few mid-20th century buildings in Montana, especially rural Montana, are so expressive of the modernist ethos, with the flat roofs, the long, low wings and the prominent chimney as a design element. Then there are the round steel stilts on which the building rests. As this mural suggests, today Hot Springs embraces its deep past as a place of sacred meaning to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai. And it continues to try to find a way to attract visitors as a 21st century, non-traditional hot springs resort.

As this mural suggests, today Hot Springs embraces its deep past as a place of sacred meaning to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai. And it continues to try to find a way to attract visitors as a 21st century, non-traditional hot springs resort. Plains is the second largest town in Sanders County, noted as the home of the county fairgrounds, the center of the local agricultural economy, and like Thompson Falls a significant place along the Clark’s Fork River and the Montana Highway 200 corridor.

Plains is the second largest town in Sanders County, noted as the home of the county fairgrounds, the center of the local agricultural economy, and like Thompson Falls a significant place along the Clark’s Fork River and the Montana Highway 200 corridor.

century feel, be it in institutions, such as the local Grange above, or the continuation of the local VFW hall and bowling alley, below.

century feel, be it in institutions, such as the local Grange above, or the continuation of the local VFW hall and bowling alley, below.

The Noxon Dam was finished in 1959. It is a mile in length, 260 feet in height and 700 feet wide at its base. Its generators can power approximately 365,000 homes, making it the second-largest capacity hydroelectric facility in Montana.

The Noxon Dam was finished in 1959. It is a mile in length, 260 feet in height and 700 feet wide at its base. Its generators can power approximately 365,000 homes, making it the second-largest capacity hydroelectric facility in Montana. Today visitors can view the dam from various parking areas and short walking trails, one of which passes over the historic line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The property has interpretive signs about the history of the project as well as about the engineering of hydroelectric power.

Today visitors can view the dam from various parking areas and short walking trails, one of which passes over the historic line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The property has interpretive signs about the history of the project as well as about the engineering of hydroelectric power. Along the banks of the river/reservoir, a much more recent public park has opened–with public sculpture reminding everyone of the Native Americans who once camped along the

Along the banks of the river/reservoir, a much more recent public park has opened–with public sculpture reminding everyone of the Native Americans who once camped along the river at this place. By bringing the deep past of the region in view of the modern, this site is a new favorite place–wherever you are in Montana, and there are many modern engineering marvels–the Indians were always there first, using those same natural resources in far different ways.

river at this place. By bringing the deep past of the region in view of the modern, this site is a new favorite place–wherever you are in Montana, and there are many modern engineering marvels–the Indians were always there first, using those same natural resources in far different ways.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core. The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century. Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks.

Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks. But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.