Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

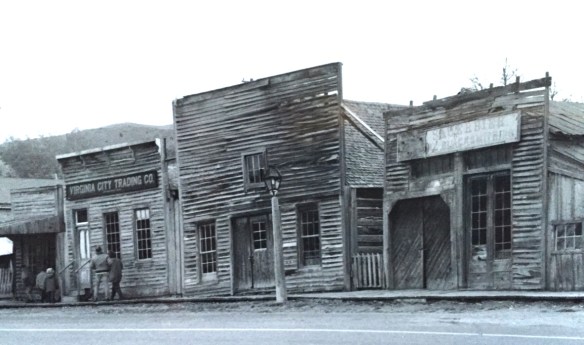

As I discussed in the article, “the Bovey family spent its own money and raised funds to restore Virginia City, then largely abandoned and in decay, to its appearance during the years the town served as a major western mining center and the territorial capital of Montana. Like the Williamsburg restoration, which focused on one key story—the revolution—in its depiction of history, the Virginia City restoration also showcased one dramatic event—the vigilante movement for law and order of the late 1860s. Success at Virginia City led the restoration managers to expand their exhibits to the neighboring “ghost town” of Nevada City, where they combined the few remaining original structures with historic buildings moved from several Montana locations to create a “typical” frontier town.”

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

property and keep both Virginia City and the recreated Nevada City open to the public.” The black and white photos I am sharing here come from a trip in 1990 that I specifically took to record Virginia City as the restored town out of the fear that the place would be dismantled, and this unique experiment in preservation lost.

About ten years ago, I was given the opportunity to return to Virginia City and to see what the public efforts had brought to the town. At that time local and state officials were interested in pursuing heritage area designation. That did not happen but it was a time when I began to understand even larger stories at Virginia City than 20 years earlier.

One of the “new” properties I considered this decade in my exploration of Virginia City was its historic cemetery. Yes, like tens of thousands of others I had been to and given due deference to “Boot Hill,” and its 20th century markers for the vigilante victims

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

There are hand-cut stone grave houses, placed above ground–the burial is actually below the ground, but the houses for mid-19th century Americans symbolized home, family, and the idea that the loved one had “gone home.” The one at the Virginia City Cemetery has a “flat roof” while I am more accustomed to a sharp gable roof on such structures.

The cast-metal prefabricated grave markers, according to early literature on the topic, are “rare.” Compared to masonry markers, yes these Victorian era markers are few in number. But they are not particularly rare; I have found them in rural and small town cemeteries across the South. They are here in Virginia City too.

One of the most prominent belonged to Union Civil War veteran, and Kentucky native, James E. Callaway, who served in the Illinois state legislature after the war, in 1869, but then came to Virginia City and served as secretary to the territorial government from 1871 to 1877. He also was a delegate to both constitutional conventions in the 1880s. He died in Virginia City in 1905.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Another property type I ignored in 1984-85 during my work in Virginia City was the impact of the New Deal. The town has a wonderful WPA-constructed community hall/ gymnasium, which is still used for its original purposes.

The impact of the Montana Heritage Foundation and the concerted state effort beginning in the mid-1990s has been profound on Virginia City. There has been a generation of much needed work of collection management at the curatorial center, shown below. The Boveys not only collected and restored buildings in the mid-20th century, they also packed them with “things”–and many of these are very valuable artifacts of the territorial through early statehood era.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

more than a “quaint, Old West” experience–they can actually learn about the rigors, challenges, and opportunities of the gold rush frontier in the northern Rockies.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

Here in 2016, the preservation community is commemorating the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act. The impact of that federal legislation has been truly significant, and can be found throughout the state. But the earlier efforts by families, local communities, and state governments to save what they could of the past, in some cases to market it as a heritage tourism asset, in other cases, to save it for themselves, must also be commemorated. Virginia City begins the state’s preservation story in many ways–and it will always need our attention.

In thinking about returning to Montana in 2012 and carrying out a huge “re-survey” of the places I had explored for the state historic preservation plan process 30 years earlier, Butte was high on my list of priorities. Not that the city and its surroundings had been given little attention in the early 1980s–the Copper City was already recognized as a National Historic Landmark, and a team of historians, architects, and engineers had just finished a large study of its built environment for the Historic American Building Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record. No, I wanted to go back because by 1985 many people counted Butte down and out, yet it had survived and started to reinvent itself. Not

In thinking about returning to Montana in 2012 and carrying out a huge “re-survey” of the places I had explored for the state historic preservation plan process 30 years earlier, Butte was high on my list of priorities. Not that the city and its surroundings had been given little attention in the early 1980s–the Copper City was already recognized as a National Historic Landmark, and a team of historians, architects, and engineers had just finished a large study of its built environment for the Historic American Building Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record. No, I wanted to go back because by 1985 many people counted Butte down and out, yet it had survived and started to reinvent itself. Not as a ghost town or the skeleton of a great mining city but as a revitalized place, both economically and culturally, centered in a strong core community, even though the challenges in front of it remain daunting, even overwhelming at times.

as a ghost town or the skeleton of a great mining city but as a revitalized place, both economically and culturally, centered in a strong core community, even though the challenges in front of it remain daunting, even overwhelming at times. The environmental degradation left when the hard rock mines shut down is one burden that Butte has shouldered, with the help of the federal superfund program. Still, no matter how scientifically this landscape has been “cleaned up,” it remained scarred, and it is a far different challenge to build back hope into a place stripped of its life. Yet high over the city is a sign of the change to come in the Mountain Con Mine site.

The environmental degradation left when the hard rock mines shut down is one burden that Butte has shouldered, with the help of the federal superfund program. Still, no matter how scientifically this landscape has been “cleaned up,” it remained scarred, and it is a far different challenge to build back hope into a place stripped of its life. Yet high over the city is a sign of the change to come in the Mountain Con Mine site. Still labeled as a Mile High and a Mile Deep place, the mine property is stunning, not only for its technological assertion–imagine working that high, and going that deep–but for its conversion into the walking/hiking/biking trails that encircle the city and present it with such potential as a recreational landscape.

Still labeled as a Mile High and a Mile Deep place, the mine property is stunning, not only for its technological assertion–imagine working that high, and going that deep–but for its conversion into the walking/hiking/biking trails that encircle the city and present it with such potential as a recreational landscape.

ago, with all sorts of signs of new investment, new pride, and community identity. It may have lost a step, or two, and its swagger may not be quite as exaggerated as it was in the mid-20th century, but it remains a place with its own feel, its own funk. For me, the reopening of the M&M Bar on Main Street–a legendary dive once shuttered, reopened, and shuttered again–gives me hope for Butte in the 21st century. Around the corner is

ago, with all sorts of signs of new investment, new pride, and community identity. It may have lost a step, or two, and its swagger may not be quite as exaggerated as it was in the mid-20th century, but it remains a place with its own feel, its own funk. For me, the reopening of the M&M Bar on Main Street–a legendary dive once shuttered, reopened, and shuttered again–gives me hope for Butte in the 21st century. Around the corner is

Mercury Street; at the same time the sex trade was alive and well to the east of that same street in a series of boarding houses and hotels. The Dumas Brothel, discussed in an earlier post, is listed in the National Register and its future as an adaptive reuse project and place for public interpretation is promising but not yet realized. African Americans in

Mercury Street; at the same time the sex trade was alive and well to the east of that same street in a series of boarding houses and hotels. The Dumas Brothel, discussed in an earlier post, is listed in the National Register and its future as an adaptive reuse project and place for public interpretation is promising but not yet realized. African Americans in

The massive building still dominates the Uptown building, making its closure in Butte in 1980 that more disturbing for residents. When I did my preservation plan work in 1984-1985 the issue of what to do with the Hennessy was at the forefront. By the end of the decade, ENTECH renovated the building and reopened it fully for business. In 2010 came the popular Hennessy Market–giving the growing number of Uptown residents a grocery store once again.

The massive building still dominates the Uptown building, making its closure in Butte in 1980 that more disturbing for residents. When I did my preservation plan work in 1984-1985 the issue of what to do with the Hennessy was at the forefront. By the end of the decade, ENTECH renovated the building and reopened it fully for business. In 2010 came the popular Hennessy Market–giving the growing number of Uptown residents a grocery store once again. The Sliver Bow Club building (1906-7) also has shifted its purpose, from being the stately and eloquent clubhouse of the city’s elite to becoming a place for public offices and meetings in its once exclusive spaces. Originally conceived by the same Spokane architects who designed the Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park, according to recent research by museum curator and preservationist Patty Dean, the building’s architects ended up being Link and Haire, the noted Montana architectural firm.

The Sliver Bow Club building (1906-7) also has shifted its purpose, from being the stately and eloquent clubhouse of the city’s elite to becoming a place for public offices and meetings in its once exclusive spaces. Originally conceived by the same Spokane architects who designed the Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park, according to recent research by museum curator and preservationist Patty Dean, the building’s architects ended up being Link and Haire, the noted Montana architectural firm.

Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

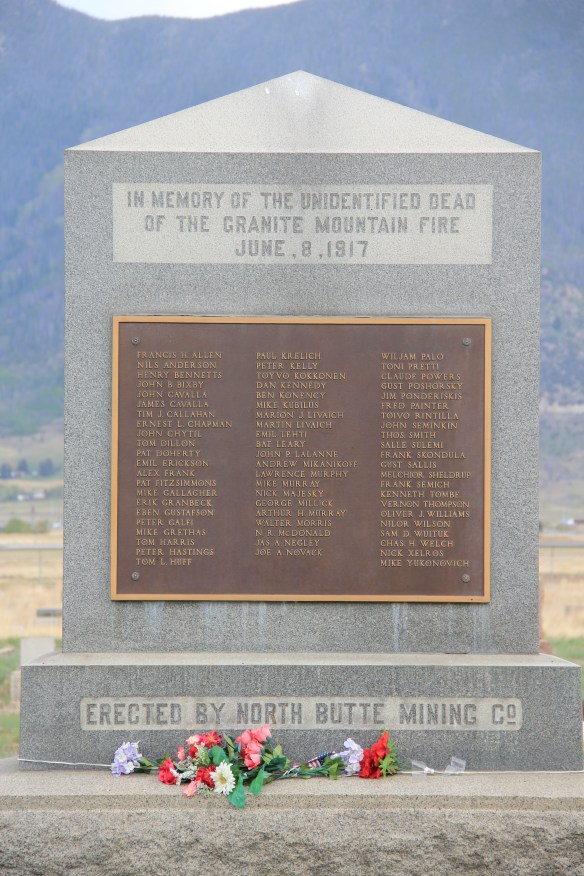

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot.

interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot. The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation.

Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation. Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others