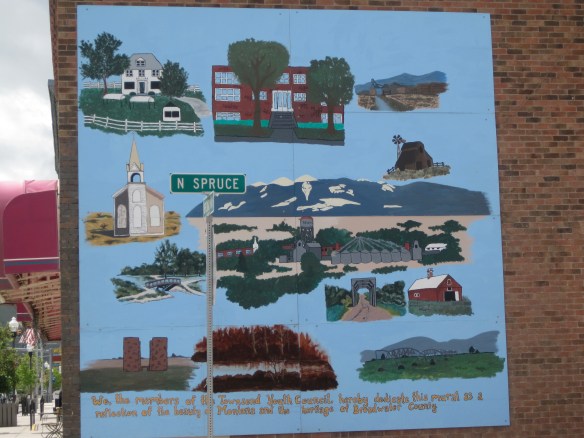

A week ago a colleague from Tennessee told me of returning to Cut Bank–a family place that she had not been to in decades–and we talked of what a great, classic town it is, and how the town uses blank walls to tell their own story to the hordes of tourists who pass through on U.S. Highway 2 on their way to Glacier National Park. The homesteader-theme mural is just one of the several that enliven the streets and instruct those who wish to stop, look, think.

Montana’s art and history have always been closely linked as even those in the first generation of settlement commissioned artists, Charles M. Russell and Edgar Paxson, to paint historical murals for the new state capitol building in Helena. Then came the public art commissions of the New Deal era, such as the work of J. K. Raulston (below),

which once hung in the Richland County Courthouse in Sidney (and now displayed at the Mondak Heritage Center in Sidney) and the numerous murals that graced new post offices and federal buildings across Montana, the one below from Dillon demonstrates

which once hung in the Richland County Courthouse in Sidney (and now displayed at the Mondak Heritage Center in Sidney) and the numerous murals that graced new post offices and federal buildings across Montana, the one below from Dillon demonstrates

that the arts program of the 1930s stretched across Montana, from Sidney to Dillon.

that the arts program of the 1930s stretched across Montana, from Sidney to Dillon.

When I lived in Helena in the first half of the 1980s, of course I noticed murals, such as one above on the state’s important women’s history on Last Chance Gulch, which itself had various installations of interpretive sculpture to tell the story of a place that had been so “renewed” as to lose all meaning.

When I lived in Helena in the first half of the 1980s, of course I noticed murals, such as one above on the state’s important women’s history on Last Chance Gulch, which itself had various installations of interpretive sculpture to tell the story of a place that had been so “renewed” as to lose all meaning.

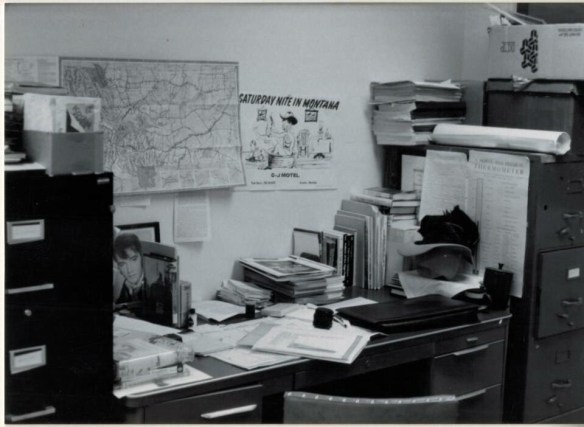

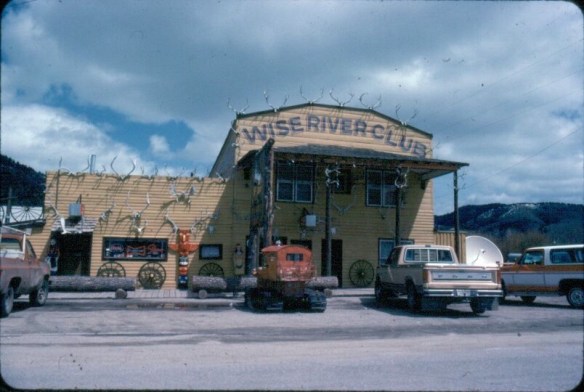

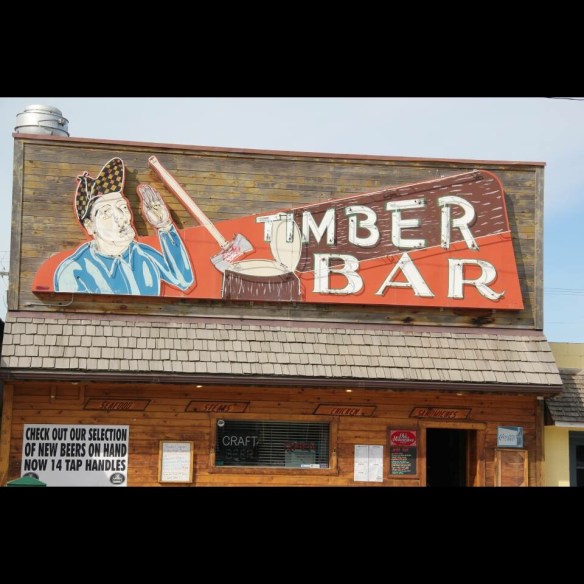

In my second shot at documenting the historic landscape of Montana, in the first half of this decade, I couldn’t help but notice how many places used murals to tell their story, or to hint about what mattered to those who traveled by–they truly were everywhere. On the walls of cafe/bars like at Melrose:

Or they could be at old service stations at once important crossroads, like at Jordan:

Scenes of landscape and animals–the wild side of Montana are common:

A grizzly at Libby, Montana.

A bison at the Western Chick Cafe in Broadus.

But many tell a story, perhaps no more elaborately than in Columbia Falls, where the historic Masonic Lodge is wrapped in a mural that links the town to its logging beginnings to the establishment of the town and merchants.

Another northwestern Montana town–the gateway town of Eureka on U.S. Highway 89. uses a mural to set the scene of a quiet, peaceful place no matter the season:

Another northwestern Montana town–the gateway town of Eureka on U.S. Highway 89. uses a mural to set the scene of a quiet, peaceful place no matter the season:

Whereas at Troy–another gateway town at the western edge of Montana on U.S. Highway 2–the town name itself is emblazoned on a building–you can’t miss it.

Many towns highlight their history with murals. The one in Townsend (below), on U.S. Highway 12, reminds me of a common heritage-centered art piece found everywhere–a quilt with each square representing a different community or place name.

Others are more pointed in their message. A lone tractor in a field stands out in Chester, the seat of Liberty County:

Wilsall, on U.S. 89 north of Livingston, tells a rather elaborate story–of days when the town was vibrant and its railroad as an important link between the region and the state.

In Fairview, at the North Dakota border, a mural depicts the historic Noyly bridge, an engineering marvel that sits now out of town, forgotten excepts by locals.

Butte perhaps has the most effective set of public art to tell its story–where there was so little 30 years ago there are interpretive settings throughout the town of past glory days and key events, topped by a monumental mural in the heart of Uptown.

As a trend in public interpretation, I love the generation of new public art in Montana as much as admire the art of the New Deal era that adorns and emboldens our post offices. All of these creative expressions (the mural below is from Deer Lodge) remind anyone that the past is always present in the Big Sky Country.

In late may I return to the Big Sky Country, my first visit in two years, when I will once again be looking for changes in the historic built environment as I speed along the state’s

In late may I return to the Big Sky Country, my first visit in two years, when I will once again be looking for changes in the historic built environment as I speed along the state’s highways and backroads, crossing the bridges over the Yellowstone River, and trying my best to catch as many Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railroad freight trains as possible, although I doubt that I will ever have such a fun moment than in 2013 when I

highways and backroads, crossing the bridges over the Yellowstone River, and trying my best to catch as many Burlington Northern and Santa Fe Railroad freight trains as possible, although I doubt that I will ever have such a fun moment than in 2013 when I caught this freight along the original Great Northern route while I was driving on the original–still dirt and gravel–road of U.S. Highway 2 between Tampico and Vandalia.

caught this freight along the original Great Northern route while I was driving on the original–still dirt and gravel–road of U.S. Highway 2 between Tampico and Vandalia. Certainly I will keep my eye out for Montana’s famed wildlife, although I don’t expect again to see a bighorn sheep outside of Glasgow, especially one being chased by a dinosaur. I will also stay on the lookout, as regular readers of this blog well know, for the beef–it is rarely a question of where’s the beef in Montana.

Certainly I will keep my eye out for Montana’s famed wildlife, although I don’t expect again to see a bighorn sheep outside of Glasgow, especially one being chased by a dinosaur. I will also stay on the lookout, as regular readers of this blog well know, for the beef–it is rarely a question of where’s the beef in Montana. No doubt there will be both new and older historical markers to stop and read; the evolving interpretation of Montana’s roadside continues to be such a strong trend.

No doubt there will be both new and older historical markers to stop and read; the evolving interpretation of Montana’s roadside continues to be such a strong trend. And through all of the brief stay in the state–perhaps 10 days at the most–I will also stop and enjoy those local places, far removed from the chain-drives roadside culture of our

And through all of the brief stay in the state–perhaps 10 days at the most–I will also stop and enjoy those local places, far removed from the chain-drives roadside culture of our nation, where you can enjoy a great burger, rings, and shake, like Matt’s in Butte, or a good night sleep at any of the many “Mom and Pop’s” motels along the state’s highways, such as this one in Big Timber.

nation, where you can enjoy a great burger, rings, and shake, like Matt’s in Butte, or a good night sleep at any of the many “Mom and Pop’s” motels along the state’s highways, such as this one in Big Timber.

Craftsman style popular in the early 20th century. It is a place where the pages of the famous Craftsman Magazine seem to come alive as you walk the tree-lined streets. But there is more to Havre’s historic districts than the homes–there are the churches, about which more needs to be said.

Craftsman style popular in the early 20th century. It is a place where the pages of the famous Craftsman Magazine seem to come alive as you walk the tree-lined streets. But there is more to Havre’s historic districts than the homes–there are the churches, about which more needs to be said. As my first two images of the First Lutheran Church show, Gothic Revival style is a major theme in the church architecture of Havre, even extending into the mid-20th century. First Lutheran Church is a congregation with roots in Havre’s boom during the homesteading era. As the congregation grew, members decided to build the present building in 1050-51, adding an educational wing by the end of the decade.

As my first two images of the First Lutheran Church show, Gothic Revival style is a major theme in the church architecture of Havre, even extending into the mid-20th century. First Lutheran Church is a congregation with roots in Havre’s boom during the homesteading era. As the congregation grew, members decided to build the present building in 1050-51, adding an educational wing by the end of the decade.

The earliest Gothic Revival styled church is First Baptist Church, constructed c. 1901, shown above. The unidentified architect combined Gothic windows into his or her own interpretation of Victorian Gothic, with its distinctive asymmetrical roof line.

The earliest Gothic Revival styled church is First Baptist Church, constructed c. 1901, shown above. The unidentified architect combined Gothic windows into his or her own interpretation of Victorian Gothic, with its distinctive asymmetrical roof line. A more vernacular interpretation of Gothic style can be found in the town’s original AME Church, built c. 1916 to serve African American railroad workers and their families, and later converted and remodeled into the New Hope Apostolic Church.

A more vernacular interpretation of Gothic style can be found in the town’s original AME Church, built c. 1916 to serve African American railroad workers and their families, and later converted and remodeled into the New Hope Apostolic Church.

The Spanish Colonial Revival style of St. Jude’s Catholic Church, however, shows us that architect Frank F. Bossuot was more than a classicist. The church’s distinctive style sets it apart from other church buildings in Havre.

The Spanish Colonial Revival style of St. Jude’s Catholic Church, however, shows us that architect Frank F. Bossuot was more than a classicist. The church’s distinctive style sets it apart from other church buildings in Havre. The same can be said for a church building that comes a generation later, the Van Orsdel United Methodist Church. When the Havre historic district was established, this mid-century modernist designed building was not yet 50 years old, thus it was not considered for the district. But certainly now, in 2018, the contemporary styling of the sanctuary has merit, and the church has a long history of service. It started just over one hundred years ago with a brick building named in honor of the Montana Methodist circuit rider W. W. Van Orsdel who introduced the faith to Havre in 1891. A fire in late 1957 destroyed that building, and the congregation immediately began construction on its replacement, dedicating it in 1958.

The same can be said for a church building that comes a generation later, the Van Orsdel United Methodist Church. When the Havre historic district was established, this mid-century modernist designed building was not yet 50 years old, thus it was not considered for the district. But certainly now, in 2018, the contemporary styling of the sanctuary has merit, and the church has a long history of service. It started just over one hundred years ago with a brick building named in honor of the Montana Methodist circuit rider W. W. Van Orsdel who introduced the faith to Havre in 1891. A fire in late 1957 destroyed that building, and the congregation immediately began construction on its replacement, dedicating it in 1958.

The work was still underway then, but the result after 30 years of local investment and engagement, assisted mightily by the state historic preservation office and other state groups, is impressive. The Grand Union is a riverfront anchor on one of the nation’s most important river towns in all of U.S. history.

The work was still underway then, but the result after 30 years of local investment and engagement, assisted mightily by the state historic preservation office and other state groups, is impressive. The Grand Union is a riverfront anchor on one of the nation’s most important river towns in all of U.S. history. The success of the Grand Union is mirrored in another property I visited in my 1984 day and a half in Fort Benton: the reconstructed Fort Benton. There were bits of the adobe blockhouse and walls still standing in 1984, as they had for decades as shown in the old postcard below.

The success of the Grand Union is mirrored in another property I visited in my 1984 day and a half in Fort Benton: the reconstructed Fort Benton. There were bits of the adobe blockhouse and walls still standing in 1984, as they had for decades as shown in the old postcard below.

chops away and the beer is still cold. That is what you need on the road.

chops away and the beer is still cold. That is what you need on the road.

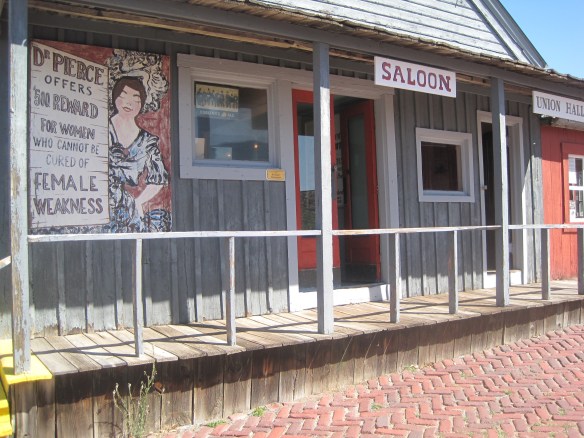

The Hell Roaring’ Gulch part of the museum is in stark contrast to the mid-20th century engineered, technological landscape of the Orphan Girl Mine. It interprets the mining camp days of Butte from the late 1860s into the 1880s before the corporations stepped in and reshaped the totality of the copper mining industry and built environment of Butte.

The Hell Roaring’ Gulch part of the museum is in stark contrast to the mid-20th century engineered, technological landscape of the Orphan Girl Mine. It interprets the mining camp days of Butte from the late 1860s into the 1880s before the corporations stepped in and reshaped the totality of the copper mining industry and built environment of Butte.

artifacts and banners shown in this photo); the store, which displays common items sought by the miners and their families; and various offices that show the business of

artifacts and banners shown in this photo); the store, which displays common items sought by the miners and their families; and various offices that show the business of mapping the mines, registering claims, and assaying the metals .

mapping the mines, registering claims, and assaying the metals . In my first post about the World Museum of Mining, I addressed this valuable collection of a historic mine, several historic buildings, and thousands of historic artifacts briefly. Properties like the impressive log construction of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, shown below, are invaluable. The World Museum of Mining deserved more attention, and it deserves the attention of any serious heritage tourist to Montana.

In my first post about the World Museum of Mining, I addressed this valuable collection of a historic mine, several historic buildings, and thousands of historic artifacts briefly. Properties like the impressive log construction of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, shown below, are invaluable. The World Museum of Mining deserved more attention, and it deserves the attention of any serious heritage tourist to Montana.

Beaverhead County Montana is huge–in its area it is bigger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware combined, and is roughly the size of Connecticut. Within these vast boundaries in the southwest corner of Montana, less than 10,000 people live, as counted in the 2010 census. As this blog has previously documented, in a land of such vastness, transportation means a lot–and federal highways and the railroad are crucial corridors to understand the settlement history of Beaverhead County.

Beaverhead County Montana is huge–in its area it is bigger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware combined, and is roughly the size of Connecticut. Within these vast boundaries in the southwest corner of Montana, less than 10,000 people live, as counted in the 2010 census. As this blog has previously documented, in a land of such vastness, transportation means a lot–and federal highways and the railroad are crucial corridors to understand the settlement history of Beaverhead County. This post takes another look at the roads less traveled in Beaverhead County, such as Blacktail Creek Road in the county’s southern end. The road leads back into lakes and spectacular scenery framed by the Rocky Mountains.

This post takes another look at the roads less traveled in Beaverhead County, such as Blacktail Creek Road in the county’s southern end. The road leads back into lakes and spectacular scenery framed by the Rocky Mountains.

But along the road you find historic buildings left behind as remnants of ranches now lost, or combined into even larger spreads in the hopes of making it all pay some day.

But along the road you find historic buildings left behind as remnants of ranches now lost, or combined into even larger spreads in the hopes of making it all pay some day.

Birch Creek Road was shaped by the efforts of the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s as the Corps carried out multiple projects in the national forest. This road has a logical destination–the historic Birch Creek C.C.C. Camp, which has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The University of Montana Western uses the property for outdoor education and as a conference center that is certainly away from everything.

Birch Creek Road was shaped by the efforts of the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s as the Corps carried out multiple projects in the national forest. This road has a logical destination–the historic Birch Creek C.C.C. Camp, which has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The University of Montana Western uses the property for outdoor education and as a conference center that is certainly away from everything.

which once hung in the Richland County Courthouse in Sidney (and now displayed at the Mondak Heritage Center in Sidney) and the numerous murals that graced new post offices and federal buildings across Montana, the one below from Dillon demonstrates

which once hung in the Richland County Courthouse in Sidney (and now displayed at the Mondak Heritage Center in Sidney) and the numerous murals that graced new post offices and federal buildings across Montana, the one below from Dillon demonstrates that the arts program of the 1930s stretched across Montana, from Sidney to Dillon.

that the arts program of the 1930s stretched across Montana, from Sidney to Dillon. When I lived in Helena in the first half of the 1980s, of course I noticed murals, such as one above on the state’s important women’s history on Last Chance Gulch, which itself had various installations of interpretive sculpture to tell the story of a place that had been so “renewed” as to lose all meaning.

When I lived in Helena in the first half of the 1980s, of course I noticed murals, such as one above on the state’s important women’s history on Last Chance Gulch, which itself had various installations of interpretive sculpture to tell the story of a place that had been so “renewed” as to lose all meaning.

Another northwestern Montana town–the gateway town of Eureka on U.S. Highway 89. uses a mural to set the scene of a quiet, peaceful place no matter the season:

Another northwestern Montana town–the gateway town of Eureka on U.S. Highway 89. uses a mural to set the scene of a quiet, peaceful place no matter the season: