The vast majority of my effort to document and think about the historic landscapes of Montana lie with two time periods, 1984-85 and 2012-16. But in between those two focused periods, other projects at the Western Heritage Center in Billings brought me back to the Big Sky Country. Almost always I found a way to carve out a couple of additional days to get away from the museum and study the many layers of history, and change, in the landscape by taking black and white images as I had in 1984-85. One such trip came in 1999, at the end of the 20th century.

In Billings itself I marveled at the changes that historic preservation was bringing to the Minnesota Avenue district. The creation of an “Internet cafe” (remember those?) in the McCormick Block was a guaranteed stop.

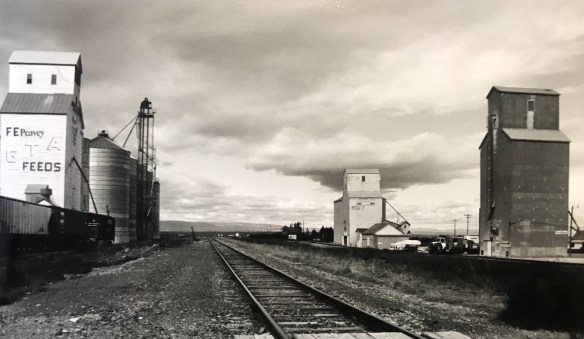

But my real goal was to jet up highways 191 and 80 to end up in Fort Benton. Along the way I had to stop at Moore, one of my favorite Central Montana railroad towns, and home to a evocative set of grain elevators.

Then a stop for lunch at the Geraldine bar and the recently restored Geraldine depot, along a historic spur of the Milwaukee Road. I have always loved a stop in this plains country town and this day was especially memorable as residents showed off what they had accomplished in the restoration. Another historic preservation plus!

Then it was Fort Benton, a National jewel seemingly only appreciated by locals, who faced an often overwhelming task for preserving and finding sustainable new uses for the riverfront buildings.

It was exciting to see the recent goal that the community eagerly discussed in 1984–rebuilding the historic fort.

A new era for public interpretation of the northern fur trade would soon open in the new century: what a change from 1984.

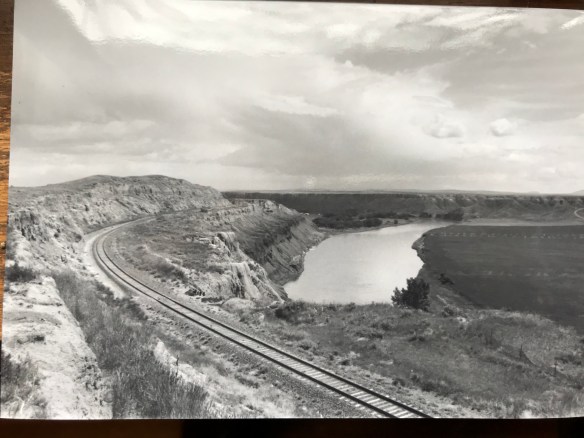

I beat a quick retreat back to the south, following the old Manitoba Road route along the Missouri and US Highway 87 and back via highway 89 to the Yellowstone Valley. I had to pay a quick tribute to Big Timber, and grab a brew at the Big Timber

Bar. The long Main Street in Big Timber was obviously changing–new residents and new businesses. Little did I know how much change would come in the new century.

One last detour came on the drive to see if the absolutely spectacular stone craftsmanship of the Absarokee school remained in place–it did, and still does.

My work in Tennessee had really focused in the late 1990s on historic schools: few matched the distinctive design of Absarokee. I had to see it again.

Like most trips in the 1990s to Billings I ended up in Laurel–I always felt this railroad town had a bigger part in the history of Yellowstone County than

generally accepted. The photos I took in 1999 are now striking– had any place in the valley changed more than Laurel in the 21st century?

The new year will mark 35 years since I began my systematic exploration of Montana for the state historic preservation office. I am using that loose anniversary (actually I started in Toole County in February) as an excuse to share some of my favorite images from a time that seems like yesterday but certainly belongs to another era. The image of a winter morning in McCabe in the northeast corner of Montana is still perhaps my favorite of all. The idea of a town being merely a handful of unadorned buildings fascinated me, and the primacy of the post office also struck me.

The new year will mark 35 years since I began my systematic exploration of Montana for the state historic preservation office. I am using that loose anniversary (actually I started in Toole County in February) as an excuse to share some of my favorite images from a time that seems like yesterday but certainly belongs to another era. The image of a winter morning in McCabe in the northeast corner of Montana is still perhaps my favorite of all. The idea of a town being merely a handful of unadorned buildings fascinated me, and the primacy of the post office also struck me. The imprint of the metropolitan corridor of great railroad corporations crossing the northern plains with their trains speeding between Seattle and St Paul never left my memory— as four decades of my graduate students will sadly attest. The image of Hoagland in northern Blaine County recorded what happened to the spur lines of the main corridors by the end of the century. The image below of Joplin along US Highway 2 is what I always think of when someone mentions the Hi-Line.

The imprint of the metropolitan corridor of great railroad corporations crossing the northern plains with their trains speeding between Seattle and St Paul never left my memory— as four decades of my graduate students will sadly attest. The image of Hoagland in northern Blaine County recorded what happened to the spur lines of the main corridors by the end of the century. The image below of Joplin along US Highway 2 is what I always think of when someone mentions the Hi-Line. Small-town Montana is also defined by its local bars and taverns, as I have repeatedly emphasized in this blog. Swede’s Place in Drummond just said a lot to me in 1984. But I wasn’t sure which door to use— the one between the glass block windows did the trick.

Small-town Montana is also defined by its local bars and taverns, as I have repeatedly emphasized in this blog. Swede’s Place in Drummond just said a lot to me in 1984. But I wasn’t sure which door to use— the one between the glass block windows did the trick. Some places I considered small town landmarks have disappeared in the last third of a century. The Antler Hotel and bar in Melstone on US Highway 12 is one I still miss.

Some places I considered small town landmarks have disappeared in the last third of a century. The Antler Hotel and bar in Melstone on US Highway 12 is one I still miss. Rural schools were everywhere even though some had been abandoned for a generation. The Boston Coulee School still had its New Deal privy. The New Deal also built the modernist styled Shawmut School. I haven’t been that way in awhile—I wonder if it still serves that tiny town.

Rural schools were everywhere even though some had been abandoned for a generation. The Boston Coulee School still had its New Deal privy. The New Deal also built the modernist styled Shawmut School. I haven’t been that way in awhile—I wonder if it still serves that tiny town.

The towns defined only by their community centers also fascinated me. Loring was bigger than Eden for what that’s worth but these comparatively substantial and obviously valued buildings told me that community meant something perhaps more profound in the Montana plains.

The towns defined only by their community centers also fascinated me. Loring was bigger than Eden for what that’s worth but these comparatively substantial and obviously valued buildings told me that community meant something perhaps more profound in the Montana plains.

I will always remember Saco fondly for the town tour that residents gave me—it ranged from an old homesteader hotel (no longer there) to a Sears Roebuck kit bungalow, which is still a family home in Saco although Sears Roebuck has largely closed up shop.

I will always remember Saco fondly for the town tour that residents gave me—it ranged from an old homesteader hotel (no longer there) to a Sears Roebuck kit bungalow, which is still a family home in Saco although Sears Roebuck has largely closed up shop.

These images are merely a beginning of my reconsideration of what I saw, heard and experienced 35 years ago but I know they represent places that still bring meaning to me today.

These images are merely a beginning of my reconsideration of what I saw, heard and experienced 35 years ago but I know they represent places that still bring meaning to me today.

A resident reported on the towns decision to join the Main Street program and how a community partnership effort had been formed to guide the process, assuring me that the wonderful historic Roundup school would find a new future as a multi-purpose and use facility. That update has spurred me to share more images from this distinctive Montana town that I have enjoyed visiting for over 30 years.

A resident reported on the towns decision to join the Main Street program and how a community partnership effort had been formed to guide the process, assuring me that the wonderful historic Roundup school would find a new future as a multi-purpose and use facility. That update has spurred me to share more images from this distinctive Montana town that I have enjoyed visiting for over 30 years. As I discussed in my earlier large posting on Roundup, it is both a railroad town on the historic mainline of the Milwaukee Road and a highway town, with a four-lane Main Street defining the commercial district. It is less than a hour’s drive north of Billings, Montana’s largest urban area. But nestled at the junction of U.S. 12 and U.S. 87, Roundup is a totally different world from booming Billings.

As I discussed in my earlier large posting on Roundup, it is both a railroad town on the historic mainline of the Milwaukee Road and a highway town, with a four-lane Main Street defining the commercial district. It is less than a hour’s drive north of Billings, Montana’s largest urban area. But nestled at the junction of U.S. 12 and U.S. 87, Roundup is a totally different world from booming Billings.

You see the difference if how false frame stores and lodge buildings from the first years of the town’s beginnings still stand, and how the commercial district is pockmarked with more stately early 20th century brick commercial blocks, whether two stories high or a mere one-story. Yet the architectural details tell you the community had ambitions. It

You see the difference if how false frame stores and lodge buildings from the first years of the town’s beginnings still stand, and how the commercial district is pockmarked with more stately early 20th century brick commercial blocks, whether two stories high or a mere one-story. Yet the architectural details tell you the community had ambitions. It

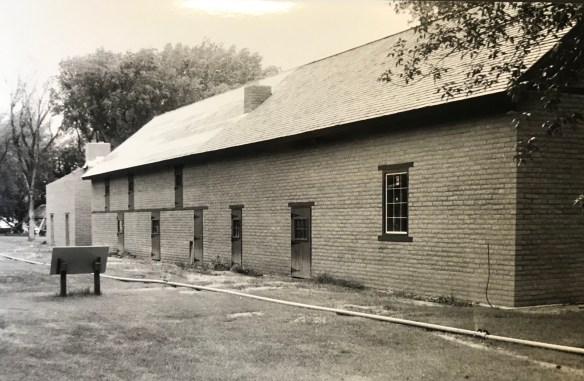

I found a place then, and still today, that was proud of its past and of its community. I visited and spoke at the county museum, which was housed in the old Catholic school and included one of county’s first homestead cabins moved to the school grounds. The nearby town park and fairgrounds (covered in an earlier post) helped to highlight just how beautiful the Musselshell River valley was at Roundup.

I found a place then, and still today, that was proud of its past and of its community. I visited and spoke at the county museum, which was housed in the old Catholic school and included one of county’s first homestead cabins moved to the school grounds. The nearby town park and fairgrounds (covered in an earlier post) helped to highlight just how beautiful the Musselshell River valley was at Roundup.

Then the public buildings–the school, the courthouse, and even the classically tinged county jail shown above–added to the town’s impressive heritage assets. Of course some buildings I ignored in the 1980s but find compelling today–like in the riverstone lined posts of the modernist Wells Fargo Bank, and the effective and efficient look of city hall.

Then the public buildings–the school, the courthouse, and even the classically tinged county jail shown above–added to the town’s impressive heritage assets. Of course some buildings I ignored in the 1980s but find compelling today–like in the riverstone lined posts of the modernist Wells Fargo Bank, and the effective and efficient look of city hall.

were so many intact details from the time of construction–built-in storage spaces, private restroom stalls, when hallway clocks ticking down the minutes in a day–the place was like a time capsule.

were so many intact details from the time of construction–built-in storage spaces, private restroom stalls, when hallway clocks ticking down the minutes in a day–the place was like a time capsule.

Intimate spaces, classroom spaces, grand public spaces. The Roosevelt School meant too much to be left to the wrecking ball, and the progress the community foundation is making there is reassuring: once again smart, effective adaptive reuse can turn a building in a sustainable heritage asset for the town. It’s worth checking out, and supporting. And it is next door to one of the state’s amazing throwback 1960s roadside

Intimate spaces, classroom spaces, grand public spaces. The Roosevelt School meant too much to be left to the wrecking ball, and the progress the community foundation is making there is reassuring: once again smart, effective adaptive reuse can turn a building in a sustainable heritage asset for the town. It’s worth checking out, and supporting. And it is next door to one of the state’s amazing throwback 1960s roadside

Standing quietly next to Forestvale Cemetery is Helena’s Odd Fellows Cemetery, formed in 1895 when several local lodges banded together to create a cemetery for its members. Most visitors to Forestvale probably think of this cemetery as just an extension of Forestvale but it is very much its own place, with ornamental plantings and an understated arc-plan to its arrangement of graves.

Standing quietly next to Forestvale Cemetery is Helena’s Odd Fellows Cemetery, formed in 1895 when several local lodges banded together to create a cemetery for its members. Most visitors to Forestvale probably think of this cemetery as just an extension of Forestvale but it is very much its own place, with ornamental plantings and an understated arc-plan to its arrangement of graves.

Compared to Forestvale, there are only a handful of aesthetically imposing grave markers, although I found the sole piece of cemetery furniture, the stone bench above, to be a compelling reminder of the reflective and commemorative purpose of the cemetery.

Compared to Forestvale, there are only a handful of aesthetically imposing grave markers, although I found the sole piece of cemetery furniture, the stone bench above, to be a compelling reminder of the reflective and commemorative purpose of the cemetery. One large stone monument, erected in the 1927 by the Rebekah lodges (for female members) of the town, marks the burial lot for IOOF members who died in Helena’s Odd Fellows Home, a building that is not extant. The memorial is a reminder of the types of social services that fraternal lodges provided their members, and how fraternal lodges shaped so much of Helena’s social and civic life in the late 19th and early twentieth century. Helena’s Odd Fellows Cemetery is a significant yet overlooked contributor to the town’s and county’s historic built environment.

One large stone monument, erected in the 1927 by the Rebekah lodges (for female members) of the town, marks the burial lot for IOOF members who died in Helena’s Odd Fellows Home, a building that is not extant. The memorial is a reminder of the types of social services that fraternal lodges provided their members, and how fraternal lodges shaped so much of Helena’s social and civic life in the late 19th and early twentieth century. Helena’s Odd Fellows Cemetery is a significant yet overlooked contributor to the town’s and county’s historic built environment.