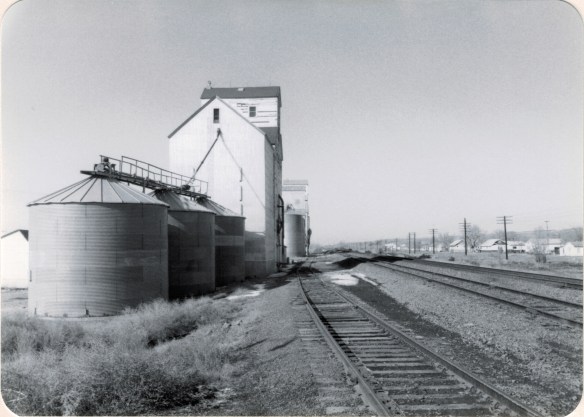

Glasgow, the seat of Valley County, dates to the late 1880s when the Manitoba Railroad (later named the Great Northern Railroad) entered the northeast corner of Montana Territory on its way west to its initial terminus in Great Falls. The first burials at what later became Highland Cemetery on a bluff northeast of the town center date to those years. The images above and below are of that first burial ground, known as Potter’s field, and part of what is designated at the first addition.

The next two images are of the cemetery’s second addition .

The section designated as Glasgow original cemetery also marks the beginning of the Highland Cemetery period. The Glasgow Montana Citizen reported on November 13, 1897: “Owing to the utter lack of system in locating the graves on the hill it was impossible to lay it [a city cemetery] out in lots so the county fathers located a strip of five acres of land adjoining the old burrying [sic] ground and laid it out into lots for future use. The cemetery is named Highland.” A couple of weeks later, the Glasgow Montana Citizen clarified the situation on December 11, 1897: The opinion prevails that the old cemetery is not a portion of the new one. This is wrong. The plat of Highland Cemetery includes a strip sixty feet wide of the old graveyard which takes in all the graves.”

Within the boundaries of the original Highland are several remarkable gravestones, many of which have fascinating stories.

For instance, Harry Wright, according to the Glasgow Record of October 15, 1896, “was one of the best known ranchers around Saco and was a prosperous young man. He had quite a nice little bunch of cattle, a comfortable ranch and was always considered one of the most promising young men of Saco.” He was returning to England for a visit when he took ill in Buffalo, New York. He had kidney surgery which “proved most successful” but before resuming his travel Wright took a “Turkish bath” [a type of steam bath] and “death came a short while afterwards.” His sister lived in Hinsdale and had the body shipped to Glasgow to be buried in the cemetery in 1897.

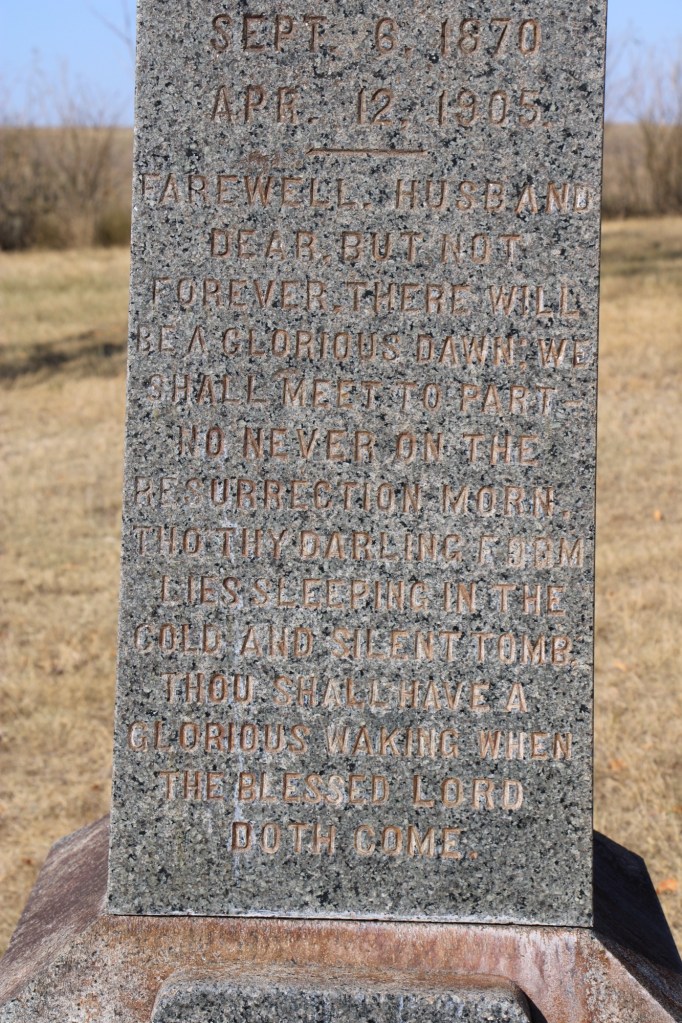

The tall obelisk marker for Lynn Benton Cook, who died at the age of 34 in 1905, has an unusually long dedication, beginning “Farewell Husband” composed by his wife Edith May.

Fredrick Whitbread has a beautiful carved marker with a Richardsonian Romanesque arch framing a depiction of salvation. He was an Englishman who came to the USA in 1881. He worked as a locomotive fireman before becoming a Great Northern engineer. He left the railroad in 1897 and established a cattle ranch near Hinsdale. However in 1907 he reversed course to become the night foreman at the Great Northern’s roundhouse in Glasgow. He was a loyal member of the Odd Fellow lodge and his funeral “was the largest in the history of this city,” according to the Glasgow Montana Citizen of April 25, 1908.

Another prominent citizen was Father James Molyneux, an Irish Catholic priest who pastored St RaphaelCatholic Church in Glasgow from 1912-1917 during the height of the county’s homesteading boom.

Perhaps the most compelling marker in the early history of Highland Cemetery is that of Mary Fitzpatrick Roach. She first came to Glasgow by 1890 when she worked as a cook at a local hotel before opening her own restaurant. During the railroad strike of 1895, she “became famous all along the Hi Line, by carrying her customers along whether they could pay or not.” (Glasgow Courier, June 5, 1931)

Her empathy and charity earned her the nickname “Mother of Glasgow,” which is carved in her gravestone. After the strike, her business grew and she owned a boarding house, a meat market, a large herd of cattle, and a lodging house. She married Porter Roach in 1907 and died two years later.

Highland Cemetery, like several other municipal cemeteries along the Hi Line, maintains an impressive Veterans section, with the four section arranged around a central flagpole.

Residents of Valley County are no doubt proud of what Highland Cemetery says about their respect for the past and those who came before. This post only begins to share the impressive grave markers and stories of this public space.

One of the very few historical markers in Montana that touches on the state’s irrigation history focuses about a historic bridge that once stood nearby at Tampico.

One of the very few historical markers in Montana that touches on the state’s irrigation history focuses about a historic bridge that once stood nearby at Tampico.

Large man-made lakes capture water to reserve it for use throughout the growing season. The images above are of Fresno Reservoir, on a rainy morning, in Hill County. While the two images below are of Nelson Reservoir, on a typically bright sunny day, many miles downstream in Phillips County.

Large man-made lakes capture water to reserve it for use throughout the growing season. The images above are of Fresno Reservoir, on a rainy morning, in Hill County. While the two images below are of Nelson Reservoir, on a typically bright sunny day, many miles downstream in Phillips County.

The Milk River Project shapes so much of the Hi-Line, it has become just part of the scenery. I wonder how many travelers along U.S. Highway 2 in Phillips County even notice or consider the constant presence of the ditch along their route.

The Milk River Project shapes so much of the Hi-Line, it has become just part of the scenery. I wonder how many travelers along U.S. Highway 2 in Phillips County even notice or consider the constant presence of the ditch along their route.

is a tiny place, almost 20 miles from the county seat of Malta. But at the time of the Milk River Project, Dodson was vital; the ditch neatly divided the town into two halves, and a major diversion dam was just west of town. Here was a perfect place, at the turn of the century, for a fairgrounds. And it is a gorgeous historic fairgrounds.

is a tiny place, almost 20 miles from the county seat of Malta. But at the time of the Milk River Project, Dodson was vital; the ditch neatly divided the town into two halves, and a major diversion dam was just west of town. Here was a perfect place, at the turn of the century, for a fairgrounds. And it is a gorgeous historic fairgrounds.

buildings, the rather different design of the post office from the 1960s and the vernacular Gothic beauty of the historic Methodist Church, especially the Victorian brackets of its bell tower.

buildings, the rather different design of the post office from the 1960s and the vernacular Gothic beauty of the historic Methodist Church, especially the Victorian brackets of its bell tower.

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now. New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do.

New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do. You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.