Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

The pass is one of the infrequently visited jewels of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, a place that the expedition used and probably would have never “discovered” if not for the prior Native American use.

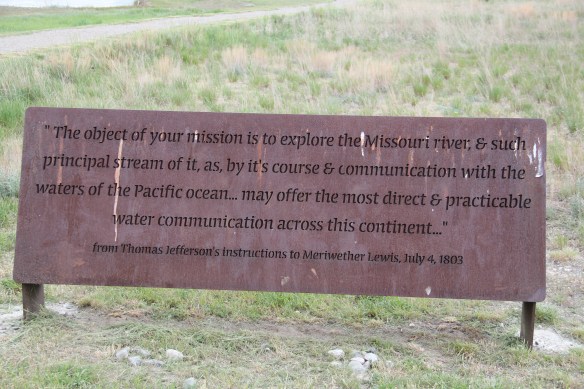

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area.

Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

marker explains that railroad engineers used the pass to connect Dillon and Idaho in the early 20th century, changing the ancient appearance of the pass, used by Native Americans for centuries to connect the high plains of Montana to the rich valleys of Idaho. The marker also describes the use of Bannock Pass by Nez Perce led by Chief Joseph in 1877, as they escaped back into Idaho after the Battle of Big Hole. The Nez Perce National Historic Trail is more closely associated with Chief Joseph Pass, located to the north.

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

Kudos to the National Park Service for its new visitor center, exhibits, and interpretive markers at the battlefield–the finally the whole story of the Nez Perce campaign is explored through thoughtful public interpretation, centered on the Nez Perce perspective,

those who lived here until the military force led by Col. John Gibbon thought it could surprise and rout the Indians. Rather the Nez Perce counter-attacked forcing the soldiers into surrounding woods. The trek of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce effort to find safety in

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks. The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention.

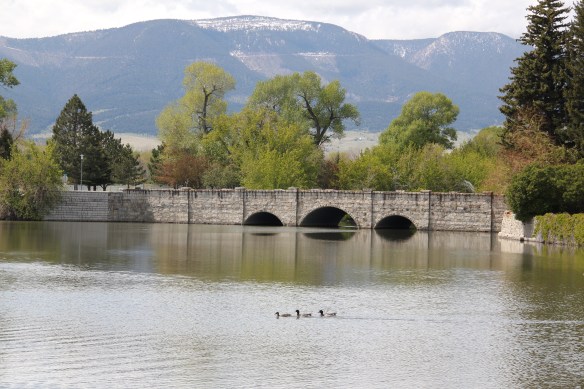

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention. Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community. Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.