Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

Professional staff and volunteers, all led by Ellen Crain, keep both the community and scholars engaged–the number of strong histories, public projects, and exhibits that have come, in whole or in part, from this place in the last 30 years is very impressive. Plus it is

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

Now an interpretive monument talks about the union, the bombing, and addresses directly a chilling chapter in the long struggle between labor and capital in Butte. Installed c. 1993 near the “top” of Main Street, this site sets the stage for the amount of public interpretation found in the city today.

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

interpretation efforts, it is also a place for community gatherings, such as the Montana Folklife Festival in recent years. It is important to note that the marker at the Original just doesn’t celebrate the technology it also notes how many men–43–died at that mine. The progress of Butte happened on the back of its working class miners.

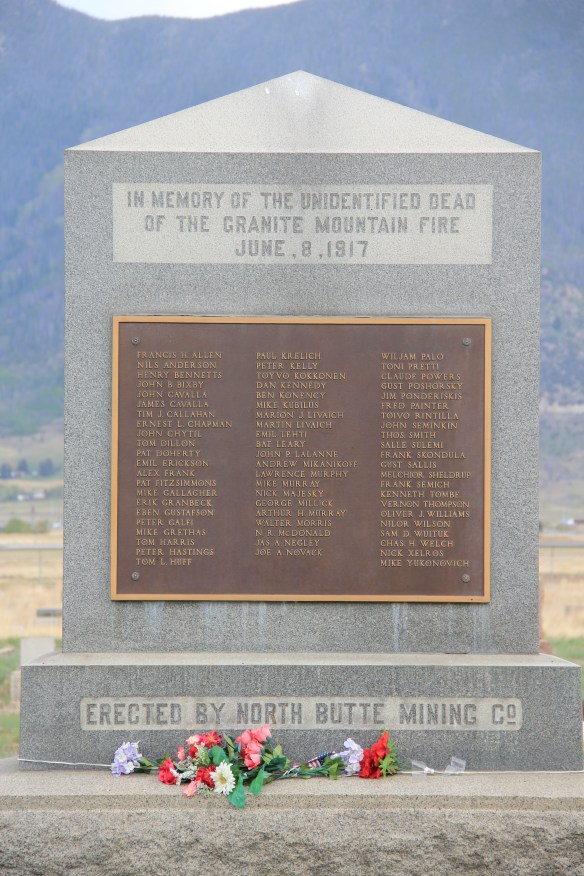

Here is another promising change: the willingness to landmark and discuss the human costs of mining. Butte’s most infamous event was the Granite Mountain/ Speculator Mine disaster of 1917 in which 168 miners died–still the single most deadly disaster in American hard-rock mining history. Not that the event was ignored at the time. In fact the North Butte mining company erected the memorial above to those who perished in Mountain View Cemetery, far from the scene, shortly thereafter. Who knew this memorial existed? There were no signs marking the way there–you had to search to find it.

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

ARCO, along with public partners, funded the site in this century, as part of the general Superfund cleanup of the mining district. But the park was long overdue as well as the recognition that some 2,500 miners lost their lives in the Butte district. The marker’s statement–“you are standing on hallowed ground”–is typically reserved for military parks. Within the context of Butte, however, it is totally justified, and an important point to remember wherever you are in the city.

The reality that Butte’s mines contributed significantly to American war efforts in the 20th century is recalled through a public art mural near a public transit stop. Public sculpture also interprets what was and what has been lost in Butte.

Through the efforts of the state historic preservation office, and its commendable program of providing interpretive markers for National Register properties, the residential side of Butte’s story is also being told. You have to love the “blue” house, associated with U.S. Senator Burton K. Wheeler, one of the New Deal era movers and shakers.

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the

interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot.

interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot.

The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

Then of course, designed for highway travelers and tourists, there is the now classic World Museum of Mining, established in 1965 around the Orphan Girl mine. The WMM lets rusting industrial artifacts convey part of the story while the existing mining buildings are open, allowing you to get a more physical experience of what the head frames and mines were really about. And, as typical of Montana museums of the 1960s and 1970s, there is the attached “frontier village,” interpreting what early Butte was all about. Don’t get me

wrong: there are many things to like about the WMM–it is rich in artifacts, as the miners items above suggest (and more about it in another post). But it is a controlled, sterile experience, and I would hate for that to be the only takeaway visitors have about Butte and its significance. The museum is away from uptown Butte, and visitors who stop here may never go explore the deeper story within the town and its historic neighborhoods.

Old Butte Historical Adventures on Main Street is just one group of heritage entrepreneurs who provide visitors with a “up close and personal” viewpoint and experience of Butte’s historic landscape. Walking tours of Uptown along with various special theme tours engage visitors and residents with local history in a way different from traditional monuments, markers, and historic sites.

But one must be aware that the pressure to commercialize can also distort, and demean, the significance of it all. What happens at the Dumas Hotel–a historic brothel–will be interesting to watch. The story of prostitution is very much part of the fabric of the city, but one that for many years people did not want to tell, except with snide references and a snicker or two. Let’s hope that changes as the Dumas is restored and opened as a heritage venue: addressing the sex trade and role of women and men accurately and in context would add immeasurably to the sense of authenticity, of realism, in the Butte story.

The most exciting part of Butte’s heritage development to my mind are the series of greenways or trails that link the mines to the business and residential districts and that link Butte to neighboring enclaves like Centerville (shown above). Recreational opportunity–walking, jogging, boarding, biking–is a huge component of livable spaces for the 21st century. When these trails are enhanced by the stories they touch or cover,

they become even more meaningful and valuable. If you have lived in Montana for 6 months or 60 years, it is time to return to Butte and take the Montana Copperway (trailhead shown above) –not only would it be good for your health, it also gives you a lasting perspective of a mining town within the vast Northern Rockies landscape, and how men and women from all sorts of backgrounds and nations established a real community, one that has outlasted the mines that first created it.

On Bozeman’s Main Street today there is a huge mural celebrating the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1882. The impact of the railroad on the town was certainly a topic of interest in the 1984-85 survey, and one image included the existing Northern Pacific Railroad and adjoining grain elevators and other businesses reliant on the corridor.

On Bozeman’s Main Street today there is a huge mural celebrating the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1882. The impact of the railroad on the town was certainly a topic of interest in the 1984-85 survey, and one image included the existing Northern Pacific Railroad and adjoining grain elevators and other businesses reliant on the corridor. Today that same place has been transformed, through adaptive reuse, into a micro-brewery and restaurant–pretty good place too, and a great place in 2015 for me to get out of a persistent rain. The Northern Pacific reached a deal with rancher Nelson Story in 1882 to build through his property but also provide a spur line to his existing mill operations. From the beginning both the railroad and local entrepreneurs saw an agricultural future for Bozeman and Gallatin County.

Today that same place has been transformed, through adaptive reuse, into a micro-brewery and restaurant–pretty good place too, and a great place in 2015 for me to get out of a persistent rain. The Northern Pacific reached a deal with rancher Nelson Story in 1882 to build through his property but also provide a spur line to his existing mill operations. From the beginning both the railroad and local entrepreneurs saw an agricultural future for Bozeman and Gallatin County.

The depot and adjoining buildings have been designated as a historic district, with a pocket city park providing some new life to the area. But this impressive building’s next life remains uncertain even as the city encourages creative solutions for the area.

The depot and adjoining buildings have been designated as a historic district, with a pocket city park providing some new life to the area. But this impressive building’s next life remains uncertain even as the city encourages creative solutions for the area.

The c. 1922 depot is adequately moth-balled–the new roof has lots of life left–and as the city maintains it is structurally sound with key interior features intact. Yet graffiti now mars one end of the building, and any building that is empty, especially in such a booming local economy, is cause for concern.

The c. 1922 depot is adequately moth-balled–the new roof has lots of life left–and as the city maintains it is structurally sound with key interior features intact. Yet graffiti now mars one end of the building, and any building that is empty, especially in such a booming local economy, is cause for concern.

The same fate did not befell the Milwaukee Road’s other significant building in Bozeman, its concrete block warehouse, shown above in an 1985 image. The open space, solid construction, and excellent location helped to ensure a much longer life for the building, which is now a building supplies store, with a repainted company sign adorning the elevations of the building.

The same fate did not befell the Milwaukee Road’s other significant building in Bozeman, its concrete block warehouse, shown above in an 1985 image. The open space, solid construction, and excellent location helped to ensure a much longer life for the building, which is now a building supplies store, with a repainted company sign adorning the elevations of the building.

It is encouraging that the city recognizes the significance, and the possibilities, for the historic buildings along Bozeman’s railroad corridor. Let’s hope that a permanent solution soon emerges for the empty Northern Pacific depot.

It is encouraging that the city recognizes the significance, and the possibilities, for the historic buildings along Bozeman’s railroad corridor. Let’s hope that a permanent solution soon emerges for the empty Northern Pacific depot.

Then Senator Moss took me for a quick tour of its late 1990s renovation in 2007–its conversion into law offices respected both its original spaces and interior design.

Then Senator Moss took me for a quick tour of its late 1990s renovation in 2007–its conversion into law offices respected both its original spaces and interior design.

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention.

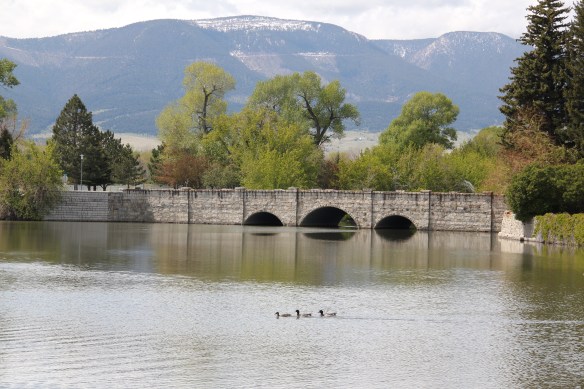

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention. Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community. Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

As the highway leaves the central plains east of Great Falls, it heads east through coal country (see the earlier post on Belt) and south into the Little Belt Mountains and the old mining towns of Monarch and Neihart (above). Both Cascade County towns are proud of their heritage, a story embodied in the Monarch-Neihart School, a wonderful bit of log craftsmanship from the New Deal era, a WPA project finished in 1940 that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

As the highway leaves the central plains east of Great Falls, it heads east through coal country (see the earlier post on Belt) and south into the Little Belt Mountains and the old mining towns of Monarch and Neihart (above). Both Cascade County towns are proud of their heritage, a story embodied in the Monarch-Neihart School, a wonderful bit of log craftsmanship from the New Deal era, a WPA project finished in 1940 that is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When I last visited there in 2015 the combined route of U.S. 89 and 12, which passes in front of the courthouse and the center of town, was being rebuilt, giving the historic business district the look of a ghost town.

When I last visited there in 2015 the combined route of U.S. 89 and 12, which passes in front of the courthouse and the center of town, was being rebuilt, giving the historic business district the look of a ghost town.

U.S. Highway 89 continues south, crossing the historic corridor of the Milwaukee Road at Ringling, another Meagher County town discussed in an earlier post, marked by the landmark St. John’s Catholic Church.

U.S. Highway 89 continues south, crossing the historic corridor of the Milwaukee Road at Ringling, another Meagher County town discussed in an earlier post, marked by the landmark St. John’s Catholic Church. Travelers continuing south soon find themselves in Park County, entering the Shields River Valley just north of Wilsall, where highway markers and monuments, like that for “Thunder Jack” (2006) by sculptor Gary Kerby, convey the significance of the place.

Travelers continuing south soon find themselves in Park County, entering the Shields River Valley just north of Wilsall, where highway markers and monuments, like that for “Thunder Jack” (2006) by sculptor Gary Kerby, convey the significance of the place.

Wilsall was not much a place 30 years ago, a small trade town on the edge of a Northern Pacific Railroad spur line, a past still recalled by the tall elevator and old railroad corridor.

Wilsall was not much a place 30 years ago, a small trade town on the edge of a Northern Pacific Railroad spur line, a past still recalled by the tall elevator and old railroad corridor. But the growing popularity of the Shields River Valley has led to a new boom in Walsall, with old banks converted into bars and old general stores

But the growing popularity of the Shields River Valley has led to a new boom in Walsall, with old banks converted into bars and old general stores

Clyde Park Tavern is still the place to go for an adult beverage, or two. Historic grain elevators still serve local ranchers, marking the railroad line that defined the town’s landscape until the impact of the highway in the early 20th century.

Clyde Park Tavern is still the place to go for an adult beverage, or two. Historic grain elevators still serve local ranchers, marking the railroad line that defined the town’s landscape until the impact of the highway in the early 20th century.