The last post addressed Montana’s famous ranching landscape. Intermixed with the ranches, especially in the eastern third of the state, is a very different landscape of technology, one of pumps, storage facilities, pipelines, and refineries–the oil landscape of 20th and 21st century Montana.

The last post addressed Montana’s famous ranching landscape. Intermixed with the ranches, especially in the eastern third of the state, is a very different landscape of technology, one of pumps, storage facilities, pipelines, and refineries–the oil landscape of 20th and 21st century Montana.

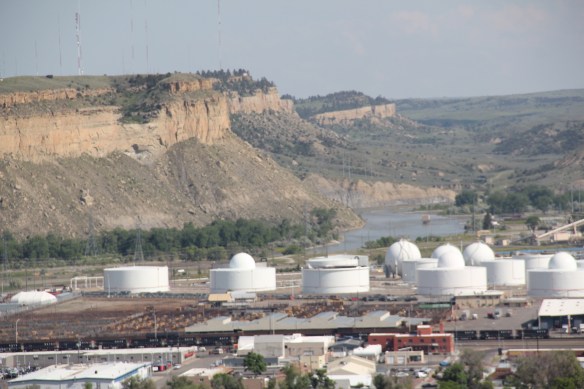

Billings is the largest city in Montana, and oil refineries along the railroad lines, are a major reason why. At the beginning of the 20th century, Billings was not close to being the largest town in the Yellowstone Valley–both Glendive and Livingston held that honor. But due to its railroad network, and the rise of oil from the 1940s onward, Billings had far surpassed any place in the Yellowstone, and, in fact, had become the largest city of the northern plains. Go up on the bluffs overlooking the city and it is easy to see how oil has impacted this place.

Billings boomed in the mid-20th century because of oil–and the impact spread throughout the county. The former Cenex refinery at Laurel–the next railstop to the west–dominates the town’s exit on Interstate Highway I-90.

Yellowstone County is the distribution center for oil and petroleum in Montana. The production areas can be found in almost any eastern county, where companies have established wells that pump crude non-stop–there are few oil fields here but plenty of pumps within the fields of Montana.

The number of pumps stretched across the landscape amazed me during the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan fieldwork. I didn’t really think of oil when I thought about Montana back then. The focus 30 years ago was not on the transformative boom that had begun ten years earlier but we did know enough to consider the earlier boom from the 1920s which began at a place called Cat Creek in what became Petroleum County in central

Petroleum County Courthouse in Winnett is listed in the National Register.

Montana to the similar 1920s boom, which lasted a good deal longer, in east side of the Rockies next to the Canadian border in Toole and Glacier counties. Cut Bank, the seat of

Glacier County, still bragged about its role as the “north oil center” in 1984. To the south of Cut Bank at Kevin, you can still find both active and historic resources associated with the region’s oil production.

The towns of Kevin and Oilmont, however, have lost hundreds of residents since the boom–their deteriorating buildings tell a common Montana story of boom and bust, the patterns of extractive industries everywhere.

The former Oilmont School.

Now I wonder what will be the fate of the sudden boom towns of the fracking excitement of the early 21st century. When I planned my fieldwork for the revisit to the Montana landscape, I decided that I must go to the eastern counties first–places like Plentywood, Sheridan, Culbertson, etc., because they would be the next to transform due to the Baker

field expansion. Fracking I found–like in Roosevelt County above–but fractured communities–not so much, as I have discussed in earlier posts. And now the boom has subsided–for how long? International markets will decide.

No matter what happens, Montana’s oil landscape will remain, past and present, and become one of the layers of history that speaks to how technology and international markets shaped the Big Sky Country.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

Kremlin never grew to be much, perhaps 300 residents at its height (around 100 today), not because it never participated in the region’s agricultural boom–the decaying elevators speak to prosperity but a tornado and then drought doomed the town to being a minor player along the Great Northern main line.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley. The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

Bozeman has boomed with many new chef-driven restaurants but of the downtown establishments my favorite for good fresh, creative food remains the Co-Op Downtown nestled within the Gallatin Block, a historic building, tastefully renovated, in the downtown historic district.

Bozeman has boomed with many new chef-driven restaurants but of the downtown establishments my favorite for good fresh, creative food remains the Co-Op Downtown nestled within the Gallatin Block, a historic building, tastefully renovated, in the downtown historic district.

head to Miles City, which is the place to go if you wonder, still, “where’s the beef” and a city that is the proud home of the famous Montana Bar.

head to Miles City, which is the place to go if you wonder, still, “where’s the beef” and a city that is the proud home of the famous Montana Bar.

within New Deal landscape that forever changed the look of this region in the 1930s. Locals and tourists mix together–because the hotel is the only place to go, unless you want to backtrack to Glasgow and check out Sam’s Supper Club on U.S. Highway 2, and its equally neat 1960s roadside look.

within New Deal landscape that forever changed the look of this region in the 1930s. Locals and tourists mix together–because the hotel is the only place to go, unless you want to backtrack to Glasgow and check out Sam’s Supper Club on U.S. Highway 2, and its equally neat 1960s roadside look.

The most popular Montana gateway into Yellowstone National Park is at Gardiner, in the southern tip of Park County. Here is where the Northern Pacific Railway stopped its trains, at a Rustic styled passenger station long ago demolished, and travelers passed through the gate above–designed by architect Robert Reamer–and started their journey into the park.

The most popular Montana gateway into Yellowstone National Park is at Gardiner, in the southern tip of Park County. Here is where the Northern Pacific Railway stopped its trains, at a Rustic styled passenger station long ago demolished, and travelers passed through the gate above–designed by architect Robert Reamer–and started their journey into the park. By the mid-20th century, Gardiner had become a highway town, the place in-between the beautiful drive through the Paradise Valley on U.S. Highway 89 (now a local paved road)

By the mid-20th century, Gardiner had become a highway town, the place in-between the beautiful drive through the Paradise Valley on U.S. Highway 89 (now a local paved road)

The plan to develop a new Gardiner library at the old Northern Pacific depot site at part of the Gardiner Gateway Project is particularly promising, giving the town a new community anchor but also reconnecting it to the railroad landscape it was once part of. Something indeed to look for when I next visit this Yellowstone Gateway.

The plan to develop a new Gardiner library at the old Northern Pacific depot site at part of the Gardiner Gateway Project is particularly promising, giving the town a new community anchor but also reconnecting it to the railroad landscape it was once part of. Something indeed to look for when I next visit this Yellowstone Gateway. Montana’s gateways into Yellowstone National Park are known far and wide. The most popular are associated with the trains that delivered mostly easterners to the wonderland of the park–West Yellowstone for the Union Pacific line and Gardiner for the Northern Pacific Railway.

Montana’s gateways into Yellowstone National Park are known far and wide. The most popular are associated with the trains that delivered mostly easterners to the wonderland of the park–West Yellowstone for the Union Pacific line and Gardiner for the Northern Pacific Railway. Cooke City, located in the corner of Park County, was never a railroad town but an overland connection that did not become popular until the development of the Beartooth Highway out of Red Lodge in the 1920s.

Cooke City, located in the corner of Park County, was never a railroad town but an overland connection that did not become popular until the development of the Beartooth Highway out of Red Lodge in the 1920s. It is all about the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) here–when it opens, Cooke City booms as a tourism oasis. When the highway closes for its long winter, business doesn’t end since the road to Mammoth Hot Springs far to the west is kept open as best as it can be, but the number of visitors drops remarkably. Snow mobile traffic in the winter has meant a lot to local business in the last 30 years.

It is all about the Beartooth Highway (U.S. 212) here–when it opens, Cooke City booms as a tourism oasis. When the highway closes for its long winter, business doesn’t end since the road to Mammoth Hot Springs far to the west is kept open as best as it can be, but the number of visitors drops remarkably. Snow mobile traffic in the winter has meant a lot to local business in the last 30 years.

Cooke City uses its mining past to define its identity today, from moving log mining shacks and cabins into town, as shown above, for potential new lures for tourism, to the recently established visitor center and museum, which includes some of the local mining

Cooke City uses its mining past to define its identity today, from moving log mining shacks and cabins into town, as shown above, for potential new lures for tourism, to the recently established visitor center and museum, which includes some of the local mining

Perhaps the best example is the rustic yet modern styling of the Mt Republic Chapel of Peace between Silver Gate and Cooke City on U.S. 212. It is no match for the soaring mountains that surround it but its quiet dignity reflects well the people and environment of this part of Montana.

Perhaps the best example is the rustic yet modern styling of the Mt Republic Chapel of Peace between Silver Gate and Cooke City on U.S. 212. It is no match for the soaring mountains that surround it but its quiet dignity reflects well the people and environment of this part of Montana.

The same can be said for Hoosier’s Bar–a favorite haunt here in Cooke City for several decades, easy to find with its neon sign, and then there is the throwback telephone booth–a good idea since many cell phones search for coverage in this area. Cooke City and Silver Gate are the smallest Montana gateways into Yellowstone National Park but they tell and preserve their story well.

The same can be said for Hoosier’s Bar–a favorite haunt here in Cooke City for several decades, easy to find with its neon sign, and then there is the throwback telephone booth–a good idea since many cell phones search for coverage in this area. Cooke City and Silver Gate are the smallest Montana gateways into Yellowstone National Park but they tell and preserve their story well.