In the first half of the 20th century, Anaconda gained its reputation as a hard-working town, whether you toiled at the smelter, the pottery works, the railroad, or any of the many small businesses and shops across the city. With that hard work came the need

for places to rest, relax, and enjoy the precious hours away from the workplace. So much has changed in Anaconda since the closing of the smelter in the early 1980s–but the town’s distinctive places for recreation and relaxation remain, a big part of the reason Anaconda is one of my favorite places in Montana.

for places to rest, relax, and enjoy the precious hours away from the workplace. So much has changed in Anaconda since the closing of the smelter in the early 1980s–but the town’s distinctive places for recreation and relaxation remain, a big part of the reason Anaconda is one of my favorite places in Montana.

Let’s start with the magnificent Art Deco marvel of the Washoe Theater. Designed in 1930 by B. Marcus Priteca but not finished and opened until 1936, the theater has stayed in operation ever since. It is remarkably intact, especially when owners refused to follow the multi-screen craze of the 1970s and kept the lobby and massive screen

Let’s start with the magnificent Art Deco marvel of the Washoe Theater. Designed in 1930 by B. Marcus Priteca but not finished and opened until 1936, the theater has stayed in operation ever since. It is remarkably intact, especially when owners refused to follow the multi-screen craze of the 1970s and kept the lobby and massive screen

intact. It was a favorite jaunt in the 1980s to go to Anaconda, take in a movie at the Washoe and then cocktails at the Club Moderne. The interior design is attributed to Hollywood designer Nat Smythe.

A drink after the movie: still happens with regularity in Anaconda, due to the plethora of neighborhood bars, from the Anaconda Bar to the Thompson Bar. The range of sizes and styling speaks to the different experiences offered by these properties.

A drink after the movie: still happens with regularity in Anaconda, due to the plethora of neighborhood bars, from the Anaconda Bar to the Thompson Bar. The range of sizes and styling speaks to the different experiences offered by these properties.

The Locker Room Bar has a classic Art Deco look with its green glass and glass block entrance while the JFK Bar documents its date of construction while the rock veneer on concrete is undeniably a favorite construction technique of the 1960s.

If not the bars, then you could retreat to your fraternal lodge or veterans group. Fraternal lodges were everywhere once in Anaconda and several historic ones still survive. The Croatian Hall, unassuming in its size and ornament, is one of the most interesting lodges on the east side, in the old “Goosetown” working-class part of Anaconda. Sam Premenko established the club in Anaconda’s early years.

The Elks Club in the heart of downtown is a totally different statement, with its sleek 1960s modernist facade over an earlier turn of the century Victorian styled brick building reflecting a more prosperous and larger membership.

The Elks Club in the heart of downtown is a totally different statement, with its sleek 1960s modernist facade over an earlier turn of the century Victorian styled brick building reflecting a more prosperous and larger membership.

With its glass block entrances and windows, the American Legion lodge seems like another lounge, but the American Eagle mural says otherwise.

With its glass block entrances and windows, the American Legion lodge seems like another lounge, but the American Eagle mural says otherwise.

The Copper Bowl is a wonderful mid-20th century reminder of both the raw material that fueled Anaconda. From the highway sign–a great piece of roadside architecture itself–you can see the slag piles from the smelter. Bowling, so popular once, is disappearing across the country, except in Anaconda, where two different set of lanes remained in business–at least in 2012.

If not bowling, why not read a book. At least that was the motivation behind Progressive reformers and their initiative to create “free” (meaning no membership fees) public libraries at the turn of the 20th century. Anaconda has one of the state’s earliest and most architecturally distinctive libraries in the Hearst Free Library.

If not bowling, why not read a book. At least that was the motivation behind Progressive reformers and their initiative to create “free” (meaning no membership fees) public libraries at the turn of the 20th century. Anaconda has one of the state’s earliest and most architecturally distinctive libraries in the Hearst Free Library.

Funded by Phoebe Hearst (mother of William Randolph Hearst), the library reflected a Renaissance Revival style in red brick designed by San Francisco architect F. S. Van Trees. It opened in 1898 and served as an inspiring public space, part library, part public meeting space, part art museum.

Another Progressive-era institution is Washoe Park, established by the copper company and home to the first fish hatchery in the state. Washoe Park was a place for outdoor recreation, with ball fields, picnic areas, and amusement attractions. It also was home for the town’s baseball field and its historic grandstands and refreshment

Another Progressive-era institution is Washoe Park, established by the copper company and home to the first fish hatchery in the state. Washoe Park was a place for outdoor recreation, with ball fields, picnic areas, and amusement attractions. It also was home for the town’s baseball field and its historic grandstands and refreshment

center still serve those who come to see. The Anaconda Copper Company had the diamond and grandstand built c. 1949 and the first teams to play were organized by the city’s different fraternal lodges. Besides the classic look of the grandstand nearby

is the refreshment/ recreation center, a building in the Rustic style, an architectural type associated with parks of all sorts in the first half of the 20th century.

New renovations at the park have been underway, improving trails, the hatchery, and the outdoor experience plus adding public interpretation at appropriate places. The park is being re-energized but respect still shown its early elements, such as the historic Alexander Glover cabin, built c. 1865 and identified as the oldest residence in Anaconda, which was moved into the park as an interpretive site, early, c. 1920.

New renovations at the park have been underway, improving trails, the hatchery, and the outdoor experience plus adding public interpretation at appropriate places. The park is being re-energized but respect still shown its early elements, such as the historic Alexander Glover cabin, built c. 1865 and identified as the oldest residence in Anaconda, which was moved into the park as an interpretive site, early, c. 1920.

Another outdoor recreational space that has been receiving renovation is the historic Mitchell Stadium complex, a New Deal project of the Works Progress Administration from 1938-1939. The stadium, designed to give the high school modern facilities for football and track and field, is quite the place, retaining so much of its original understated Art Deco styling.

Another outdoor recreational space that has been receiving renovation is the historic Mitchell Stadium complex, a New Deal project of the Works Progress Administration from 1938-1939. The stadium, designed to give the high school modern facilities for football and track and field, is quite the place, retaining so much of its original understated Art Deco styling.

Unlike Washoe Park, here was a new public space, in keeping with the New Dealers’ faith in recreation and community, that was not a creation of the copper company for adult workers but for high school athletes.

Unlike Washoe Park, here was a new public space, in keeping with the New Dealers’ faith in recreation and community, that was not a creation of the copper company for adult workers but for high school athletes.

It also is a property that I totally overlooked in the 1984-85 survey. True it was not 50 years old then but it was a WPA project that deserved close scrutiny as part of the larger federal effort to improve high school education and public spaces.

Certainly one of the most interesting conversions of industrial landscape into recreation landscape–on a whole another scale from the rails to trails movement–is how the grounds of the original smelter site at Anaconda have been transformed into a modern golf course. Rare is the opportunity to play a round but also walk around and consider public interpretation of a blasted out mining property.

But even on the links of this innovative adaptive reuse project you cannot escape the overwhelming presence of the copper company stack, and mounds of devastation it left behind. Here is an appropriate view that sums up the company influence on the distinctive place of Anaconda.

But even on the links of this innovative adaptive reuse project you cannot escape the overwhelming presence of the copper company stack, and mounds of devastation it left behind. Here is an appropriate view that sums up the company influence on the distinctive place of Anaconda.

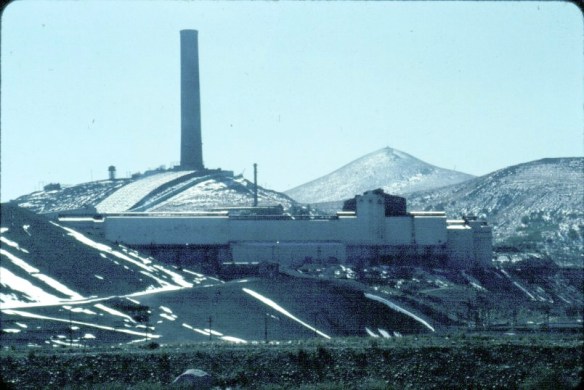

In my work across Montana in 1984-85 there was no more imposing structure than the smelter stack and works at Anaconda, in Deer Lodge County. The image above was one I used in the 20 plus listening sessions I had across the state in 1984, gathering perspectives and recommended properties for the state historic preservation plan. I used the stack because the smelter had just closed–and how this chapter in the state’s mining history could be preserved was on many minds.

In my work across Montana in 1984-85 there was no more imposing structure than the smelter stack and works at Anaconda, in Deer Lodge County. The image above was one I used in the 20 plus listening sessions I had across the state in 1984, gathering perspectives and recommended properties for the state historic preservation plan. I used the stack because the smelter had just closed–and how this chapter in the state’s mining history could be preserved was on many minds.

The Washoe Stack is one of the state’s most dominant man-made environments. For like the massive dams and reservoirs at Hungry Horse, Canyon Creek, and Fort Peck, there is the massiveness of the structure itself, and the thousands of surrounding acres impacted by the property. Unlike the lakes created by the dams of the first half of the 20th century, however, the stack left devastation in its wake, not recreation, not rebirth.

The Washoe Stack is one of the state’s most dominant man-made environments. For like the massive dams and reservoirs at Hungry Horse, Canyon Creek, and Fort Peck, there is the massiveness of the structure itself, and the thousands of surrounding acres impacted by the property. Unlike the lakes created by the dams of the first half of the 20th century, however, the stack left devastation in its wake, not recreation, not rebirth. The old gateway to the smelter introduces you to one lasting legacy of the stack–the tons of slag located along the highway leading in and out of Anaconda. The huge pile of

The old gateway to the smelter introduces you to one lasting legacy of the stack–the tons of slag located along the highway leading in and out of Anaconda. The huge pile of seems like some sort of black sand that has washed up on a beach rather the environmental spoils left by 100 years or production.

seems like some sort of black sand that has washed up on a beach rather the environmental spoils left by 100 years or production.

In the 1980s, the Atlantic Richfield Corporation, a later owner of the Washoe works, announced the stack’s closing and possible demolition. A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

In the 1980s, the Atlantic Richfield Corporation, a later owner of the Washoe works, announced the stack’s closing and possible demolition. A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

That the place remained so intact in the early 1980s was impressive to me–that it remains that way 30 years later is a testament to local stewardship, and continued good times. The interior design of Art Deco details also remain to treat the eye and tempt

That the place remained so intact in the early 1980s was impressive to me–that it remains that way 30 years later is a testament to local stewardship, and continued good times. The interior design of Art Deco details also remain to treat the eye and tempt

Few places in Montana, or for the nation for that matter, have benefited more from historic preservation and heritage development than Bozeman. To see a grain elevator complex find new uses and life in a century where grain elevators are typically a relic of a bygone era, tall hulking figures on the northern plains landscape, you discover that so much of our historic built environment can be re-imagined and put back into use.

Few places in Montana, or for the nation for that matter, have benefited more from historic preservation and heritage development than Bozeman. To see a grain elevator complex find new uses and life in a century where grain elevators are typically a relic of a bygone era, tall hulking figures on the northern plains landscape, you discover that so much of our historic built environment can be re-imagined and put back into use.

The town’s historic churches are other important anchors. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, St. James Episcopal Church is a distinguished statement of Gothic Revival executed in locally quarried sandstone designed by architect George Hancock of Fargo, North Dakota and built by local contractor James Campbell in 1890.

The town’s historic churches are other important anchors. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, St. James Episcopal Church is a distinguished statement of Gothic Revival executed in locally quarried sandstone designed by architect George Hancock of Fargo, North Dakota and built by local contractor James Campbell in 1890. Preservation efforts 30 years ago were focused on Main Street landmarks, with much success. But the combination of preservation and adaptive reuse has moved into the town’s railroad corridor with similar positive results, and the number of historic neighborhoods have multiplied.

Preservation efforts 30 years ago were focused on Main Street landmarks, with much success. But the combination of preservation and adaptive reuse has moved into the town’s railroad corridor with similar positive results, and the number of historic neighborhoods have multiplied.

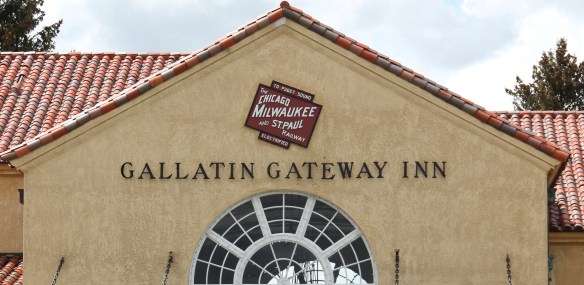

On Bozeman’s Main Street today there is a huge mural celebrating the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1882. The impact of the railroad on the town was certainly a topic of interest in the 1984-85 survey, and one image included the existing Northern Pacific Railroad and adjoining grain elevators and other businesses reliant on the corridor.

On Bozeman’s Main Street today there is a huge mural celebrating the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad in 1882. The impact of the railroad on the town was certainly a topic of interest in the 1984-85 survey, and one image included the existing Northern Pacific Railroad and adjoining grain elevators and other businesses reliant on the corridor. Today that same place has been transformed, through adaptive reuse, into a micro-brewery and restaurant–pretty good place too, and a great place in 2015 for me to get out of a persistent rain. The Northern Pacific reached a deal with rancher Nelson Story in 1882 to build through his property but also provide a spur line to his existing mill operations. From the beginning both the railroad and local entrepreneurs saw an agricultural future for Bozeman and Gallatin County.

Today that same place has been transformed, through adaptive reuse, into a micro-brewery and restaurant–pretty good place too, and a great place in 2015 for me to get out of a persistent rain. The Northern Pacific reached a deal with rancher Nelson Story in 1882 to build through his property but also provide a spur line to his existing mill operations. From the beginning both the railroad and local entrepreneurs saw an agricultural future for Bozeman and Gallatin County.

The depot and adjoining buildings have been designated as a historic district, with a pocket city park providing some new life to the area. But this impressive building’s next life remains uncertain even as the city encourages creative solutions for the area.

The depot and adjoining buildings have been designated as a historic district, with a pocket city park providing some new life to the area. But this impressive building’s next life remains uncertain even as the city encourages creative solutions for the area.

The c. 1922 depot is adequately moth-balled–the new roof has lots of life left–and as the city maintains it is structurally sound with key interior features intact. Yet graffiti now mars one end of the building, and any building that is empty, especially in such a booming local economy, is cause for concern.

The c. 1922 depot is adequately moth-balled–the new roof has lots of life left–and as the city maintains it is structurally sound with key interior features intact. Yet graffiti now mars one end of the building, and any building that is empty, especially in such a booming local economy, is cause for concern.

The same fate did not befell the Milwaukee Road’s other significant building in Bozeman, its concrete block warehouse, shown above in an 1985 image. The open space, solid construction, and excellent location helped to ensure a much longer life for the building, which is now a building supplies store, with a repainted company sign adorning the elevations of the building.

The same fate did not befell the Milwaukee Road’s other significant building in Bozeman, its concrete block warehouse, shown above in an 1985 image. The open space, solid construction, and excellent location helped to ensure a much longer life for the building, which is now a building supplies store, with a repainted company sign adorning the elevations of the building.

It is encouraging that the city recognizes the significance, and the possibilities, for the historic buildings along Bozeman’s railroad corridor. Let’s hope that a permanent solution soon emerges for the empty Northern Pacific depot.

It is encouraging that the city recognizes the significance, and the possibilities, for the historic buildings along Bozeman’s railroad corridor. Let’s hope that a permanent solution soon emerges for the empty Northern Pacific depot.

Then Senator Moss took me for a quick tour of its late 1990s renovation in 2007–its conversion into law offices respected both its original spaces and interior design.

Then Senator Moss took me for a quick tour of its late 1990s renovation in 2007–its conversion into law offices respected both its original spaces and interior design.

The district’s architectural jewel, the Dining Room, dates almost a generation later to 1926. Architect Gilbert S. Underwood designed one of the late marvels of the Rustic style as defined in the northern Rockies. With its rugged stone exterior rising as it was a natural formation in the land, the dining room immediately told arriving visitors that an adventure awaited them, especially once they stepped inside and experienced the vast log interior spaces.

The district’s architectural jewel, the Dining Room, dates almost a generation later to 1926. Architect Gilbert S. Underwood designed one of the late marvels of the Rustic style as defined in the northern Rockies. With its rugged stone exterior rising as it was a natural formation in the land, the dining room immediately told arriving visitors that an adventure awaited them, especially once they stepped inside and experienced the vast log interior spaces.

Other former Union Pacific buildings have been given adaptive reuse treatment by the town, with a baggage building becoming police headquarters and the former men’s dormitory has been converted into a local health clinic.

Other former Union Pacific buildings have been given adaptive reuse treatment by the town, with a baggage building becoming police headquarters and the former men’s dormitory has been converted into a local health clinic.

Thus, West Yellowstone is among Montana’s best examples of roadside architecture as distinctive 19502-1960w motels and a wide assortment of commercial types line both U.S. 191 but also the side arteries to the highway.

Thus, West Yellowstone is among Montana’s best examples of roadside architecture as distinctive 19502-1960w motels and a wide assortment of commercial types line both U.S. 191 but also the side arteries to the highway.

I used a slide taken in 1982 in all of my public presentations about the Montana state historic preservation plan back in 1984-1985. I found out that few Montanans knew of the place and its history. What has changed since the 1980s? The park is still little known and receives infrequent visitors. In my 2015 fieldwork, I saw signs of new heritage development–the park sign, a bit of improvement to the outdoor interpretive center, and new interpretive exhibits with a more inclusive public interpretation and strong Native American focus.

I used a slide taken in 1982 in all of my public presentations about the Montana state historic preservation plan back in 1984-1985. I found out that few Montanans knew of the place and its history. What has changed since the 1980s? The park is still little known and receives infrequent visitors. In my 2015 fieldwork, I saw signs of new heritage development–the park sign, a bit of improvement to the outdoor interpretive center, and new interpretive exhibits with a more inclusive public interpretation and strong Native American focus.

Willow Creek was the end of the line for both the Northern Pacific and Milwaukee Road railroads as they vied for dominance in turn of the 20th century western Gallatin County. The Northern Pacific came first with its spur line to Butte in the late 1880s then the Milwaukee arrived c. 1908. Both used the same corridor, along what is now called the Old Yellowstone Trail on some maps; the Willow Creek Road (MT 287) on others. It was a route that dated to 1864–the town cemetery, according to lore, dates to that year and Willow Creek has had a post office since 1867.

Willow Creek was the end of the line for both the Northern Pacific and Milwaukee Road railroads as they vied for dominance in turn of the 20th century western Gallatin County. The Northern Pacific came first with its spur line to Butte in the late 1880s then the Milwaukee arrived c. 1908. Both used the same corridor, along what is now called the Old Yellowstone Trail on some maps; the Willow Creek Road (MT 287) on others. It was a route that dated to 1864–the town cemetery, according to lore, dates to that year and Willow Creek has had a post office since 1867.

Across the street is the “employment center,” the Willow Creek Tool and Technology which sells its wares across the west out of its brick building from the 1910s. (Note the faded advertising sign that once greeted travelers on the Yellowstone Trail highway.)

Across the street is the “employment center,” the Willow Creek Tool and Technology which sells its wares across the west out of its brick building from the 1910s. (Note the faded advertising sign that once greeted travelers on the Yellowstone Trail highway.) The cultural side of Willow Creek is represented by several places: homes and galleries of different artists, a monthly arts festival in the summer, and two special buildings from the 1910s. The Stateler Memorial Methodist Church, c. 1915, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built from rusticated concrete blocks (from the cement factory at Three Forks) designed to resemble stone masonry, the church building is home to one of the oldest congregations (1864) in the Methodist Church in Montana. The Gothic Revival-styled sanctuary is named in honor of its founding minister Learner B. Stateler.

The cultural side of Willow Creek is represented by several places: homes and galleries of different artists, a monthly arts festival in the summer, and two special buildings from the 1910s. The Stateler Memorial Methodist Church, c. 1915, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built from rusticated concrete blocks (from the cement factory at Three Forks) designed to resemble stone masonry, the church building is home to one of the oldest congregations (1864) in the Methodist Church in Montana. The Gothic Revival-styled sanctuary is named in honor of its founding minister Learner B. Stateler. Nearby is another crucial landmark for any rural Montana community–the local school. The Willow Creek School is an excellent example of the standardized, somewhat Craftsman-styled designs used for rural Montana schools in the 1910s. Two stories of classrooms, sitting on a full basement, was a large school for its time, another reflection of the hopes of the homesteading era.

Nearby is another crucial landmark for any rural Montana community–the local school. The Willow Creek School is an excellent example of the standardized, somewhat Craftsman-styled designs used for rural Montana schools in the 1910s. Two stories of classrooms, sitting on a full basement, was a large school for its time, another reflection of the hopes of the homesteading era. Additions in form of a gym and added rooms had come to the north and the school and its lot is the town’s community center. Although so close to Three Forks, the school kept its

Additions in form of a gym and added rooms had come to the north and the school and its lot is the town’s community center. Although so close to Three Forks, the school kept its