Note: sorry about the delayed posts–real life, and work, interfered in October.

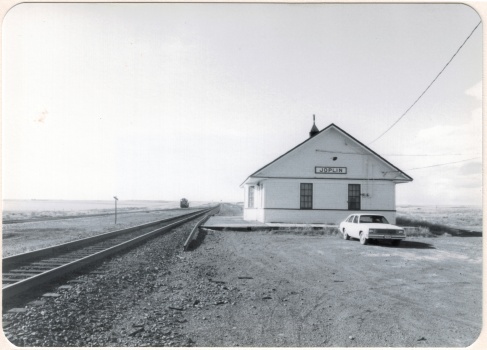

In the 1984 survey of Montana’s landscapes for the state historic preservation office, when I turned southward at the Bainville depot, a Great Northern Railway landmark now sadly missing from the landscape, I understood that a new phase of the project, and of the state, was opening up before my eyes as a cold February turned into March.

I first encountered Fairview, at the tip of the Lower Yellowstone Valley and a product too of the Lower Yellowstone Irrigation Project, which I addressed in earlier posts this fall.

Fairview then and even more so now was a place of transition between the agriculture made possible through the engineering marvel of the federal irrigation project and the slowly creeping westward push of the oil boom associated with North Dakota’s Williston Basin.

As I drove south along MT Highway 16, I passed through the Lower Yellowstone Project towns of Crane, Savage, Sidney, and Intake–discussed in earlier posts–and then hit Interstate I-94: the first interstate I had seen in weeks. But instead of turning into Glendive, the major town in the region, I veered to the east to explore Wibaux County.

I knew a bit about Wibaux through the standard narratives of Montana history because here stood the ranch house of Pierre Wibaux, one of the most famous early cattlemen in Montana. The house had long served as a heritage tourism stop, even as a state welcome center since Wibaux is positioned a few miles west of the Montana-North Dakota border on I-94. In 1984 I knew that I wanted to visit the ranch house, and see the monument erected to Wibaux to commemorate his life and achievements.

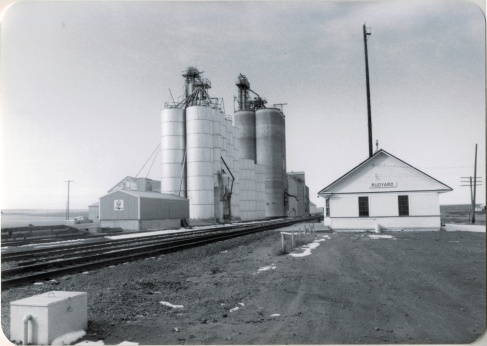

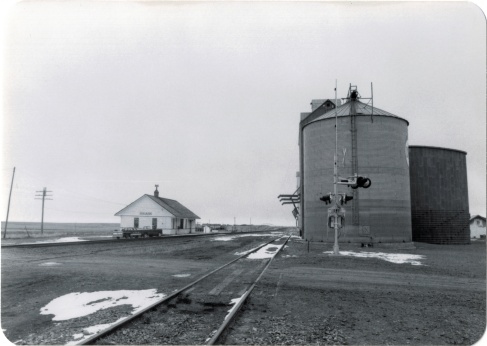

I also found, however, the heavy imprint left in the wake of the Northern Pacific Railroad as it headed into Montana and aimed for the Yellowstone Valley. For the next several weeks I explored this connection between rail and river that so defines the valley still today.

Wibaux is a town of bars–the Shamrock became my favorite in 1984, but the Rainbow Bar, housed in a building with more than a nod to Northern Pacific iconography, and the Stockman Bar were always worth a stop. Among newcomers in 2013, the Firelite was friendly but the big hit with locals and visitors was the Beaver Creek Brewery, a microbrewery way out on the plains of Montana.

With old historic hotels, business blocks, and bank buildings–one transformed into the town library–still intact, here is a commercial historic district just waiting one day to be placed into the National Register of Historic Places.

Besides the bars, however, I enjoy Wibaux for its sense of a western ranch town, even in the face of the expanding reach of the Williston oil boom. There is the 1950s contemporary-styled Wibaux County Courthouse; the county fairgrounds south of town; and a bit farther south on MT 16 the historic Nunberg Ranch, which is listed in the National Register.

Also listed in the National Register is the striking St. Peter’s Catholic Church, certainly a Gothic Revival landmark when the congregation built it on a high point west of the business district but then made into a western landmark with the addition of river stone in 1938. Here was a statement in the depression era: we are here and we are proud.

But if you turn to the north, however, on the other side of the tracks is the life of the community, the school. And this image of the high school football field is perhaps the best way to close a post about Wibaux. Yep, it is small, determined, and still here, even when many think it should have blown away decades ago.