In thinking about returning to Montana in 2012 and carrying out a huge “re-survey” of the places I had explored for the state historic preservation plan process 30 years earlier, Butte was high on my list of priorities. Not that the city and its surroundings had been given little attention in the early 1980s–the Copper City was already recognized as a National Historic Landmark, and a team of historians, architects, and engineers had just finished a large study of its built environment for the Historic American Building Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record. No, I wanted to go back because by 1985 many people counted Butte down and out, yet it had survived and started to reinvent itself. Not

In thinking about returning to Montana in 2012 and carrying out a huge “re-survey” of the places I had explored for the state historic preservation plan process 30 years earlier, Butte was high on my list of priorities. Not that the city and its surroundings had been given little attention in the early 1980s–the Copper City was already recognized as a National Historic Landmark, and a team of historians, architects, and engineers had just finished a large study of its built environment for the Historic American Building Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record. No, I wanted to go back because by 1985 many people counted Butte down and out, yet it had survived and started to reinvent itself. Not

as a ghost town or the skeleton of a great mining city but as a revitalized place, both economically and culturally, centered in a strong core community, even though the challenges in front of it remain daunting, even overwhelming at times.

as a ghost town or the skeleton of a great mining city but as a revitalized place, both economically and culturally, centered in a strong core community, even though the challenges in front of it remain daunting, even overwhelming at times.

The environmental degradation left when the hard rock mines shut down is one burden that Butte has shouldered, with the help of the federal superfund program. Still, no matter how scientifically this landscape has been “cleaned up,” it remained scarred, and it is a far different challenge to build back hope into a place stripped of its life. Yet high over the city is a sign of the change to come in the Mountain Con Mine site.

The environmental degradation left when the hard rock mines shut down is one burden that Butte has shouldered, with the help of the federal superfund program. Still, no matter how scientifically this landscape has been “cleaned up,” it remained scarred, and it is a far different challenge to build back hope into a place stripped of its life. Yet high over the city is a sign of the change to come in the Mountain Con Mine site.

Still labeled as a Mile High and a Mile Deep place, the mine property is stunning, not only for its technological assertion–imagine working that high, and going that deep–but for its conversion into the walking/hiking/biking trails that encircle the city and present it with such potential as a recreational landscape.

Still labeled as a Mile High and a Mile Deep place, the mine property is stunning, not only for its technological assertion–imagine working that high, and going that deep–but for its conversion into the walking/hiking/biking trails that encircle the city and present it with such potential as a recreational landscape.

Transformation, that it is what strikes me as I wander down the trail and into Butte’s famous, or is it infamous, “Uptown” district. Butte is far from the place it was 30 years

ago, with all sorts of signs of new investment, new pride, and community identity. It may have lost a step, or two, and its swagger may not be quite as exaggerated as it was in the mid-20th century, but it remains a place with its own feel, its own funk. For me, the reopening of the M&M Bar on Main Street–a legendary dive once shuttered, reopened, and shuttered again–gives me hope for Butte in the 21st century. Around the corner is

ago, with all sorts of signs of new investment, new pride, and community identity. It may have lost a step, or two, and its swagger may not be quite as exaggerated as it was in the mid-20th century, but it remains a place with its own feel, its own funk. For me, the reopening of the M&M Bar on Main Street–a legendary dive once shuttered, reopened, and shuttered again–gives me hope for Butte in the 21st century. Around the corner is

another institution, Gamer’s Cafe, which is situated within the marvelous Victorian eclecticism of the Curtis Music Hall of 1892.

Both establishments are for locals but visitors are tolerated, even welcomed. Indeed a degree of openness and acceptance have grown in Butte, a marked change from when the city’s Chinese residents lived and operated businesses on the edge of Uptown, along

Mercury Street; at the same time the sex trade was alive and well to the east of that same street in a series of boarding houses and hotels. The Dumas Brothel, discussed in an earlier post, is listed in the National Register and its future as an adaptive reuse project and place for public interpretation is promising but not yet realized. African Americans in

Mercury Street; at the same time the sex trade was alive and well to the east of that same street in a series of boarding houses and hotels. The Dumas Brothel, discussed in an earlier post, is listed in the National Register and its future as an adaptive reuse project and place for public interpretation is promising but not yet realized. African Americans in

early 20th century Butte lived even farther down the hill from Uptown, in a small neighborhood around Idaho Street and the Shaffers African Methodist Episcopal Church, now a pentecostal meeting house.

Uptown today is more a place for everyone, and has become the center of the community’s identity. It is easy to see why: massive, soaring buildings like the Metals Bank and Trust Tower and Hotel Finlen lend architectural dignity to the surroundings. Early 20th century classicism gives character and substance to Metals Bank whereas the Finlen has a classy

Renaissance Revival-style skin but then it has a spectacular contemporary Colonial Revival interior design, reminding us of Butte’s resurgence during the heyday of the Berkeley Pit boom from the mid-1950s through the turbulent 1960s.

The Hennessy Block is another commercial landmark, from the city’s founding generation, that has looked for a long-term solution for decades now. Built in 1898 with support from mine magnate Marcus Daly, the building housed what most consider to be the state’s first full-fledged department store, headed by and named for Daniel Hennessy. Minneapolis architect Frederick Kees designed it in a Renaissance Revival style. In 1901 the Anaconda Copper Company moved its executive offices to the top of the building, making it perhaps the leading corporate landmark in the city.

The massive building still dominates the Uptown building, making its closure in Butte in 1980 that more disturbing for residents. When I did my preservation plan work in 1984-1985 the issue of what to do with the Hennessy was at the forefront. By the end of the decade, ENTECH renovated the building and reopened it fully for business. In 2010 came the popular Hennessy Market–giving the growing number of Uptown residents a grocery store once again.

The massive building still dominates the Uptown building, making its closure in Butte in 1980 that more disturbing for residents. When I did my preservation plan work in 1984-1985 the issue of what to do with the Hennessy was at the forefront. By the end of the decade, ENTECH renovated the building and reopened it fully for business. In 2010 came the popular Hennessy Market–giving the growing number of Uptown residents a grocery store once again.

The Sliver Bow Club building (1906-7) also has shifted its purpose, from being the stately and eloquent clubhouse of the city’s elite to becoming a place for public offices and meetings in its once exclusive spaces. Originally conceived by the same Spokane architects who designed the Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park, according to recent research by museum curator and preservationist Patty Dean, the building’s architects ended up being Link and Haire, the noted Montana architectural firm.

The Sliver Bow Club building (1906-7) also has shifted its purpose, from being the stately and eloquent clubhouse of the city’s elite to becoming a place for public offices and meetings in its once exclusive spaces. Originally conceived by the same Spokane architects who designed the Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park, according to recent research by museum curator and preservationist Patty Dean, the building’s architects ended up being Link and Haire, the noted Montana architectural firm.

The interior design came yet from another important firm, William A. French and Company of St. Paul, Minnesota. Here you find one of the state’s best “Arts and Crafts Movement” themed interiors–and one of the best in the entire West.

The interior design speaks loudly to the gender and class focus of the social club. Its success set there table for Link and Haire’s next Butte masterpiece, the Beaux Arts-styled Silver Bow County Courthouse (1910-1912). Few public spaces in the state, save, perhaps the State Capitol, rival the Butte courthouse for its ornate exterior and interior, representing an overstatement of public authority and power in a city where a handful of mining interests made so many of the decisions.

Two years after it opened, the courthouse was not a refuge for those in need but a barracks for the state militia during the violence of 1914. Today, however, it is most definitely the people’s house, and was duly celebrated during its 100th birthday in 2012. It is part of the city’s distinguished public landscape, including the Victorian City Hall and the Beaux Arts classicism of the Police Department.

Of course, there is much more to see and say about Uptown Butte, but hopefully this is enough to show community pride at work, the value of historic preservation, and a proud city on the upswing, despite the obstacles before it.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school. While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students.

While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students. Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012. At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.

Cutting through Montana’s southeast corner is state highway 287, not a particularly long route at a little over 40 miles in length, but a spectacular one nonetheless as it connects the Madison River Valley (seen above) with the Ruby River Valley, with the famous mining town of Virginia City in the mountains in between.

Cutting through Montana’s southeast corner is state highway 287, not a particularly long route at a little over 40 miles in length, but a spectacular one nonetheless as it connects the Madison River Valley (seen above) with the Ruby River Valley, with the famous mining town of Virginia City in the mountains in between. We have already talked about the western gateway to the highway, the town of Twin Bridges. Now I wish to move from west to east, stopping first Sheridan and its Bethel United Methodist Church, a brick late 19th century Gothic Revival church, which is

We have already talked about the western gateway to the highway, the town of Twin Bridges. Now I wish to move from west to east, stopping first Sheridan and its Bethel United Methodist Church, a brick late 19th century Gothic Revival church, which is

The O’Brien House is also listed in the National Register. Built in 1894, this two-story brick home is another example of Sheridan’s boom following railroad development. It is a rather late example of Italianate style (typically more popular in Montana in the 1870s).

The O’Brien House is also listed in the National Register. Built in 1894, this two-story brick home is another example of Sheridan’s boom following railroad development. It is a rather late example of Italianate style (typically more popular in Montana in the 1870s).

This Craftsman-style building dates c. 1920. Along the street are several interesting examples of domestic architecture from the early 20th century. You wonder if Mill Street might not be a possible National Register historic district.

This Craftsman-style building dates c. 1920. Along the street are several interesting examples of domestic architecture from the early 20th century. You wonder if Mill Street might not be a possible National Register historic district.

Montana Highway 41 and the western side of the county is where I start, with the town of Silver Star, nestled between a spur line of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Highway 41, and Jefferson River. Gold was discovered nearby in 1866 and the town is named for a mine, but growth came more from transportation, with Silver Star serving as an early transportation stop between Virginia City and Helena in the 1870s. Today the place is best known for a privately held massive collection of mining machines, tools, and artifacts established by Lloyd Harkins, and for its rural post office that is nestled within the town’s general store.

Montana Highway 41 and the western side of the county is where I start, with the town of Silver Star, nestled between a spur line of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Highway 41, and Jefferson River. Gold was discovered nearby in 1866 and the town is named for a mine, but growth came more from transportation, with Silver Star serving as an early transportation stop between Virginia City and Helena in the 1870s. Today the place is best known for a privately held massive collection of mining machines, tools, and artifacts established by Lloyd Harkins, and for its rural post office that is nestled within the town’s general store.

valley and its irrigation systems helped to produce one of the most famous barns in the state: the Round Barn, just north of Twin Bridges. In 1882 Noah Armstrong, who had made a fortune in mining, built the barn as part of his Doncaster Stable and Stud Farm. In 1933

valley and its irrigation systems helped to produce one of the most famous barns in the state: the Round Barn, just north of Twin Bridges. In 1882 Noah Armstrong, who had made a fortune in mining, built the barn as part of his Doncaster Stable and Stud Farm. In 1933 the Bayers family acquired the barn and incorporated it into their cattle business. When I visited in 1912 the barn was still an agricultural structure, with its wedding cake shape casting a distinct profile on the landscape. In 2015, the barn was restored to a new use: as a wedding and event reception space.

the Bayers family acquired the barn and incorporated it into their cattle business. When I visited in 1912 the barn was still an agricultural structure, with its wedding cake shape casting a distinct profile on the landscape. In 2015, the barn was restored to a new use: as a wedding and event reception space.

The result is spectacular, and with their restoration in the last 30 years, the buildings are not just landmarks but busy throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

The result is spectacular, and with their restoration in the last 30 years, the buildings are not just landmarks but busy throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

The Old Hotel, a brick two-story gable-front building, also marks the town’s ascent during the early 20th century when the town achieved its highest population, about 750 in 1920. Today about half of that number call Twin Bridges home.

The Old Hotel, a brick two-story gable-front building, also marks the town’s ascent during the early 20th century when the town achieved its highest population, about 750 in 1920. Today about half of that number call Twin Bridges home. My personal favorite, and a frequent stop during the 1980s, is the Blue Anchor Bar, nestled on the first floor, with an Art Deco style redesign, in a two-story commercial block.

My personal favorite, and a frequent stop during the 1980s, is the Blue Anchor Bar, nestled on the first floor, with an Art Deco style redesign, in a two-story commercial block. Twin Bridges is a very important river junction, thus the name, where the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Ruby rivers all meet to form the Jefferson River. A public park near the confluence just south of the Montana 41/287 helps to tell that story. Nearby is the Twin Bridges School and its amazing modernist styled gymnasium.

Twin Bridges is a very important river junction, thus the name, where the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Ruby rivers all meet to form the Jefferson River. A public park near the confluence just south of the Montana 41/287 helps to tell that story. Nearby is the Twin Bridges School and its amazing modernist styled gymnasium.

When travelers, and most Montana residents even, speak of Silver Bow County, they think of Butte. Outside of the Copper City, however, are small towns and a very different way of life. To the west we have already discussed Ramsay and its beginnings as a munitions factory town during World War I. Let’s shift attention now to the southern tip of the county and two places along the historic Union Pacific spur line, the Utah Northern Railroad, into Butte.

When travelers, and most Montana residents even, speak of Silver Bow County, they think of Butte. Outside of the Copper City, however, are small towns and a very different way of life. To the west we have already discussed Ramsay and its beginnings as a munitions factory town during World War I. Let’s shift attention now to the southern tip of the county and two places along the historic Union Pacific spur line, the Utah Northern Railroad, into Butte.

when Melrose was a substantial, busy place. This 1870s-1880s history is largely forgotten today as the town has evolved into a sportsmen’s stop off Interstate I-15 due to its great access to the Big Hole River and surrounding national forests as well as the quite marvy Melrose Bar and Cafe, a classic western watering hole.

when Melrose was a substantial, busy place. This 1870s-1880s history is largely forgotten today as the town has evolved into a sportsmen’s stop off Interstate I-15 due to its great access to the Big Hole River and surrounding national forests as well as the quite marvy Melrose Bar and Cafe, a classic western watering hole. Community institutions help to keep Melrose’s sense of itself alive in the 21st century. Its school, local firehall, the historic stone St John the Apostle Catholic Mission and the modernist styled Community Presbyterian Church are statements of stability and purpose.

Community institutions help to keep Melrose’s sense of itself alive in the 21st century. Its school, local firehall, the historic stone St John the Apostle Catholic Mission and the modernist styled Community Presbyterian Church are statements of stability and purpose.

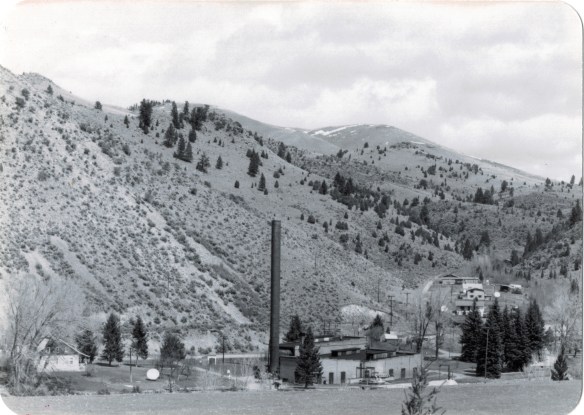

The photo above was published in A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History, in part because of the preservation excitement over this landmark but also because it documented how the boom in Butte helped to transform the historic landscape on the “other side of the divide.” The pump station took water from the Big Hole River and pumped it over the mountains to the Butte Water Company–without the pump station, expansion of the mines and the city would have been difficult perhaps impossible in the early 20th century.

The photo above was published in A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History, in part because of the preservation excitement over this landmark but also because it documented how the boom in Butte helped to transform the historic landscape on the “other side of the divide.” The pump station took water from the Big Hole River and pumped it over the mountains to the Butte Water Company–without the pump station, expansion of the mines and the city would have been difficult perhaps impossible in the early 20th century.

In 2014, in reaction to the listing of Montana rural schools as a threatened national treasure by the National Trust of Historic Preservation, CBS Sunday Morning visited Divide School for a feature story. Teacher Judy Boyle told the Montana Standard of May 16, 2014: “The town of Divide is pretty proud of its school and they want to keep it running. We have a Post Office, the Grange and the school — and if you close the school, you basically close the town.”

In 2014, in reaction to the listing of Montana rural schools as a threatened national treasure by the National Trust of Historic Preservation, CBS Sunday Morning visited Divide School for a feature story. Teacher Judy Boyle told the Montana Standard of May 16, 2014: “The town of Divide is pretty proud of its school and they want to keep it running. We have a Post Office, the Grange and the school — and if you close the school, you basically close the town.” Divide is one of many Montana towns where residents consider their schools to the foundation for their future–helping to explain why Montanans are so passionate about their local schools.

Divide is one of many Montana towns where residents consider their schools to the foundation for their future–helping to explain why Montanans are so passionate about their local schools. In thinking about returning to Montana in 2012 and carrying out a huge “re-survey” of the places I had explored for the state historic preservation plan process 30 years earlier, Butte was high on my list of priorities. Not that the city and its surroundings had been given little attention in the early 1980s–the Copper City was already recognized as a National Historic Landmark, and a team of historians, architects, and engineers had just finished a large study of its built environment for the Historic American Building Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record. No, I wanted to go back because by 1985 many people counted Butte down and out, yet it had survived and started to reinvent itself. Not

In thinking about returning to Montana in 2012 and carrying out a huge “re-survey” of the places I had explored for the state historic preservation plan process 30 years earlier, Butte was high on my list of priorities. Not that the city and its surroundings had been given little attention in the early 1980s–the Copper City was already recognized as a National Historic Landmark, and a team of historians, architects, and engineers had just finished a large study of its built environment for the Historic American Building Survey and the Historic American Engineering Record. No, I wanted to go back because by 1985 many people counted Butte down and out, yet it had survived and started to reinvent itself. Not as a ghost town or the skeleton of a great mining city but as a revitalized place, both economically and culturally, centered in a strong core community, even though the challenges in front of it remain daunting, even overwhelming at times.

as a ghost town or the skeleton of a great mining city but as a revitalized place, both economically and culturally, centered in a strong core community, even though the challenges in front of it remain daunting, even overwhelming at times. The environmental degradation left when the hard rock mines shut down is one burden that Butte has shouldered, with the help of the federal superfund program. Still, no matter how scientifically this landscape has been “cleaned up,” it remained scarred, and it is a far different challenge to build back hope into a place stripped of its life. Yet high over the city is a sign of the change to come in the Mountain Con Mine site.

The environmental degradation left when the hard rock mines shut down is one burden that Butte has shouldered, with the help of the federal superfund program. Still, no matter how scientifically this landscape has been “cleaned up,” it remained scarred, and it is a far different challenge to build back hope into a place stripped of its life. Yet high over the city is a sign of the change to come in the Mountain Con Mine site. Still labeled as a Mile High and a Mile Deep place, the mine property is stunning, not only for its technological assertion–imagine working that high, and going that deep–but for its conversion into the walking/hiking/biking trails that encircle the city and present it with such potential as a recreational landscape.

Still labeled as a Mile High and a Mile Deep place, the mine property is stunning, not only for its technological assertion–imagine working that high, and going that deep–but for its conversion into the walking/hiking/biking trails that encircle the city and present it with such potential as a recreational landscape.

ago, with all sorts of signs of new investment, new pride, and community identity. It may have lost a step, or two, and its swagger may not be quite as exaggerated as it was in the mid-20th century, but it remains a place with its own feel, its own funk. For me, the reopening of the M&M Bar on Main Street–a legendary dive once shuttered, reopened, and shuttered again–gives me hope for Butte in the 21st century. Around the corner is

ago, with all sorts of signs of new investment, new pride, and community identity. It may have lost a step, or two, and its swagger may not be quite as exaggerated as it was in the mid-20th century, but it remains a place with its own feel, its own funk. For me, the reopening of the M&M Bar on Main Street–a legendary dive once shuttered, reopened, and shuttered again–gives me hope for Butte in the 21st century. Around the corner is

Mercury Street; at the same time the sex trade was alive and well to the east of that same street in a series of boarding houses and hotels. The Dumas Brothel, discussed in an earlier post, is listed in the National Register and its future as an adaptive reuse project and place for public interpretation is promising but not yet realized. African Americans in

Mercury Street; at the same time the sex trade was alive and well to the east of that same street in a series of boarding houses and hotels. The Dumas Brothel, discussed in an earlier post, is listed in the National Register and its future as an adaptive reuse project and place for public interpretation is promising but not yet realized. African Americans in

The massive building still dominates the Uptown building, making its closure in Butte in 1980 that more disturbing for residents. When I did my preservation plan work in 1984-1985 the issue of what to do with the Hennessy was at the forefront. By the end of the decade, ENTECH renovated the building and reopened it fully for business. In 2010 came the popular Hennessy Market–giving the growing number of Uptown residents a grocery store once again.

The massive building still dominates the Uptown building, making its closure in Butte in 1980 that more disturbing for residents. When I did my preservation plan work in 1984-1985 the issue of what to do with the Hennessy was at the forefront. By the end of the decade, ENTECH renovated the building and reopened it fully for business. In 2010 came the popular Hennessy Market–giving the growing number of Uptown residents a grocery store once again. The Sliver Bow Club building (1906-7) also has shifted its purpose, from being the stately and eloquent clubhouse of the city’s elite to becoming a place for public offices and meetings in its once exclusive spaces. Originally conceived by the same Spokane architects who designed the Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park, according to recent research by museum curator and preservationist Patty Dean, the building’s architects ended up being Link and Haire, the noted Montana architectural firm.

The Sliver Bow Club building (1906-7) also has shifted its purpose, from being the stately and eloquent clubhouse of the city’s elite to becoming a place for public offices and meetings in its once exclusive spaces. Originally conceived by the same Spokane architects who designed the Lake McDonald Lodge in Glacier National Park, according to recent research by museum curator and preservationist Patty Dean, the building’s architects ended up being Link and Haire, the noted Montana architectural firm.

Far from the bustle and grime of the Richest Hill on Earth are the historic cemeteries of Butte. As I have said many times already in this blog, I rarely considered cemeteries during the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. That was a huge mistake for Butte. The three historic cemeteries I wish to consider here–Mt. Moriah, St. Patrick’s, and B’nai Israel–document the city’s ethnic diversity like few other resources, reinforcing how groups survived in a city together although they often keep to their separate communities. But the cemeteries also have sculpture and art worthy of attention and preservation–they are outstanding examples of late 19th and early 20th cemetery art and craftsmanship in the United States.

Far from the bustle and grime of the Richest Hill on Earth are the historic cemeteries of Butte. As I have said many times already in this blog, I rarely considered cemeteries during the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. That was a huge mistake for Butte. The three historic cemeteries I wish to consider here–Mt. Moriah, St. Patrick’s, and B’nai Israel–document the city’s ethnic diversity like few other resources, reinforcing how groups survived in a city together although they often keep to their separate communities. But the cemeteries also have sculpture and art worthy of attention and preservation–they are outstanding examples of late 19th and early 20th cemetery art and craftsmanship in the United States. The Masons established Mr. Moriah Cemetery Association in 1877. The cemetery has many striking markers, especially the Thompson Arches (seen above and below), an elaborate statement to mark a family plot, especially when compared to the cast-iron

The Masons established Mr. Moriah Cemetery Association in 1877. The cemetery has many striking markers, especially the Thompson Arches (seen above and below), an elaborate statement to mark a family plot, especially when compared to the cast-iron

iron fence, when combined with the carving and detail of the gravestone itself makes quite the statement for Cornish identity in Butte at the turn of the century. Note the dual fraternal lodge marks, one for the Masons, another (the linked chain) for the Odd Fellows.

iron fence, when combined with the carving and detail of the gravestone itself makes quite the statement for Cornish identity in Butte at the turn of the century. Note the dual fraternal lodge marks, one for the Masons, another (the linked chain) for the Odd Fellows.

Frank Beck left this earth in 1909, and the marker for Frank and his wife Agnes is remarkable for the inclusion of the family pet, noted above as Frank and His Faithful Dog.

Frank Beck left this earth in 1909, and the marker for Frank and his wife Agnes is remarkable for the inclusion of the family pet, noted above as Frank and His Faithful Dog.

1881 when the Hebrew Benevolent Association first acquired the land from the Northern Pacific Railroad. Congregation B’nai Israel acquired the property in 1905, two years after finishing its landmark synagogue in uptown Butte.

1881 when the Hebrew Benevolent Association first acquired the land from the Northern Pacific Railroad. Congregation B’nai Israel acquired the property in 1905, two years after finishing its landmark synagogue in uptown Butte.

The cemetery seems to stretch to the very edge of the city, but it is worth a long walk around for what you can discover about the Catholic impact on Butte in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The cemetery seems to stretch to the very edge of the city, but it is worth a long walk around for what you can discover about the Catholic impact on Butte in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are spectacular sculptural monuments to prominent city builders, such as the Classical Revival-style temple crypt for merchant price D. J. Hennessy.

There are spectacular sculptural monuments to prominent city builders, such as the Classical Revival-style temple crypt for merchant price D. J. Hennessy. Adjacent are separate plots maintained for Sisters who served and died in Butte as well as larger, more elaborate memorials for priests who served in Butte over the years.

Adjacent are separate plots maintained for Sisters who served and died in Butte as well as larger, more elaborate memorials for priests who served in Butte over the years.

Towering over the Butte cityscape, in competition with the corporate symbols of the steel head frames for dominance, are the steeples of Butte’s churches, in themselves powerful symbols of the ethnic diversity that make up the population of the copper city. This posting hardly pretends to cover all of the city’s historic churches–consider this a sampling of sacred spaces that too often are taken for granted.

Towering over the Butte cityscape, in competition with the corporate symbols of the steel head frames for dominance, are the steeples of Butte’s churches, in themselves powerful symbols of the ethnic diversity that make up the population of the copper city. This posting hardly pretends to cover all of the city’s historic churches–consider this a sampling of sacred spaces that too often are taken for granted.

Stone work in a Gothic style reminiscent of a Cotswold village parish distinguishes St. John’s Episcopal Church in Butte. Built in 1881, with later additions in the 20th century, the church is considered the oldest in the city. Copper magnate William A. Clark lived nearby and he helped to fund the church.

Stone work in a Gothic style reminiscent of a Cotswold village parish distinguishes St. John’s Episcopal Church in Butte. Built in 1881, with later additions in the 20th century, the church is considered the oldest in the city. Copper magnate William A. Clark lived nearby and he helped to fund the church. The original St. Paul Methodist Episcopal Church South (1899) was designed by architect William White in a restrained Gothic/Norman style similar to that of St. John’s Episcopal. But the real significance of the property lies with its association with miners’ attempts to organize and the influence of the International Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies) in Butte history. The property’s National Register marker summarizes it nicely: “By 1918, the church housed the Butte Daily Bulletin, a radical newspaper voicing policies of the anti-corporate Nonpartisan League, published by William F. Dunne. The office was also a known stronghold of the incendiary Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). On September 14, 1918, local police and federal troops under Major O. N. Bradley raided the Bulletin, arresting twenty-four men and thwarting a miners’ strike.”

The original St. Paul Methodist Episcopal Church South (1899) was designed by architect William White in a restrained Gothic/Norman style similar to that of St. John’s Episcopal. But the real significance of the property lies with its association with miners’ attempts to organize and the influence of the International Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies) in Butte history. The property’s National Register marker summarizes it nicely: “By 1918, the church housed the Butte Daily Bulletin, a radical newspaper voicing policies of the anti-corporate Nonpartisan League, published by William F. Dunne. The office was also a known stronghold of the incendiary Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). On September 14, 1918, local police and federal troops under Major O. N. Bradley raided the Bulletin, arresting twenty-four men and thwarting a miners’ strike.” Another Gothic landmark listed in the National Register in Butte is St. Mary’s Catholic Church, now home to a Catholic women’s foundation, on North Main Street near the federal building. The congregation was among the city’s earliest but a fire destroyed the church building leading to construction of this building at the onset of the Depression.

Another Gothic landmark listed in the National Register in Butte is St. Mary’s Catholic Church, now home to a Catholic women’s foundation, on North Main Street near the federal building. The congregation was among the city’s earliest but a fire destroyed the church building leading to construction of this building at the onset of the Depression. St. Joseph Catholic Church is quite different in its architecture, a strong statement of Classical Revival from 1911. The architect was Austrian-born Albert O. Von Verbalism, who also designed the magnificent High Victorian Gothic St. Helena Catholic Cathedral in Helena. St. Joseph is still an ethnically vibrant congregation some 100 years later.

St. Joseph Catholic Church is quite different in its architecture, a strong statement of Classical Revival from 1911. The architect was Austrian-born Albert O. Von Verbalism, who also designed the magnificent High Victorian Gothic St. Helena Catholic Cathedral in Helena. St. Joseph is still an ethnically vibrant congregation some 100 years later. The Christian Scientist Church follows the blending of Colonial and Classical Revival design so often found in the congregation’s churches no matter their location in the United States. This building dates to 1920 and Walter Arnold was the architect.

The Christian Scientist Church follows the blending of Colonial and Classical Revival design so often found in the congregation’s churches no matter their location in the United States. This building dates to 1920 and Walter Arnold was the architect. Perhaps the grandest of the Uptown religious buildings is the Onion-dome steeple of the historic B’nai Israel Synagogue (1903), which was one of three Jewish houses of worship in Butte and is now the oldest synagogue in continuous use in all of Montana.

Perhaps the grandest of the Uptown religious buildings is the Onion-dome steeple of the historic B’nai Israel Synagogue (1903), which was one of three Jewish houses of worship in Butte and is now the oldest synagogue in continuous use in all of Montana. On a far different scale is the Gold Street Lutheran Church. Built in a restrained, late interpretation of Gothic style in 1936, the church shows the continued expansion of Butte’s religious centers from the Uptown area into what is called the Flats, where so many congregations now reside.

On a far different scale is the Gold Street Lutheran Church. Built in a restrained, late interpretation of Gothic style in 1936, the church shows the continued expansion of Butte’s religious centers from the Uptown area into what is called the Flats, where so many congregations now reside.

You don’t think Montana modernism when you think of Butte, but as this overview will demonstrate, you should think about it. I have already pinpointed contemporary homes on Ophir Street (above). The copper mines remained in high production during the Cold War era and many key resources remain to document that time in the city. For discussion sake, I will introduce some of my favorites.

You don’t think Montana modernism when you think of Butte, but as this overview will demonstrate, you should think about it. I have already pinpointed contemporary homes on Ophir Street (above). The copper mines remained in high production during the Cold War era and many key resources remain to document that time in the city. For discussion sake, I will introduce some of my favorites.

I looked at schools constantly across the state in 1984-1985 but did not give enough attention to the late 1930s Butte High School, a classic bit of New Deal design combining International and Deco styles in red brick. Nor did I pay attention to the modernist buildings associated with Butte Central (Catholic) High School.

I looked at schools constantly across the state in 1984-1985 but did not give enough attention to the late 1930s Butte High School, a classic bit of New Deal design combining International and Deco styles in red brick. Nor did I pay attention to the modernist buildings associated with Butte Central (Catholic) High School.

You would think that I would have paid attention to the Walker-Garfield School since I stopped in at the nearby Bonanza Freeze, not once but twice in the Butte work of 1984. I

You would think that I would have paid attention to the Walker-Garfield School since I stopped in at the nearby Bonanza Freeze, not once but twice in the Butte work of 1984. I never gave a thought about recording this classic bit of roadside architecture either. Same too for Muzz and Stan’s Freeway Bar, although maybe I should not recount the number of stops at this classic liquor-to-go spot.

never gave a thought about recording this classic bit of roadside architecture either. Same too for Muzz and Stan’s Freeway Bar, although maybe I should not recount the number of stops at this classic liquor-to-go spot.