As the mines at Butte went into larger and larger production in the late 19th century, the railroads soon arrived to cart away the raw materials, and to deliver workers on a daily basis. All three of the famed Montana transcontinentals built facilities in Butte–in a sense 100 years ago all lines led to Butte. Remarkably, all three passenger depots remain today. The Northern Pacific depot is now an events center. The Milwaukee Road station remains a television headquarters. The Great Northern depot has been offices, a warehouse, and a bar. Its historic roundhouse also stands and it too has had many uses.

But in so many ways the real railroad story concerns a much shorter line–about 26 miles in length–but one with a big name, the Butte, Anaconda, and Pacific, designed by its founder Marcus Daly as a connector between his mines in Butte and his huge Washoe smelter in Anaconda. The BAP depot in Butte stood on Utah Street in 1985 but has been

Butte, Anaconda, and Pacific Railroad Depot, Butte, 1985

demolished, a real loss for the city’s historic fabric. Completed in 1894, the BAP connected the two cities, and its historic corridor has been recently transformed into a recreation resource that also unites the two cities and their counties. It is also a physical thread that ties together the Butte-Anaconda National Historic Landmark.

A railroad office building still stands in Anaconda, with its Romanesque arch creating an architectural theme between the office building and the BAP depot that is extant at its commanding position at the end of Main Street. Anaconda’s basic layout was

classic late 19th century railroad town planning: the depot marking the entry from railroad to town and then the long Main Street of commercial businesses culminating in the lot for the county courthouse.

View north to Deer Lodge County Courthouse from BAP depot in Anaconda.

Anaconda is also home to the extant BAP roundhouses and shapes. Like the Great Northern facility in Butte, the BAP roundhouses have had several uses, and there was a short-lived attempt to establish a railroad museum within one of the bays. The future for this important railroad structure is cloudy.

Between Butte and Anaconda two small towns have important extant historic resources. Back in the 1980s I considered Rocker to be a must stop for the It Club Bar–and it is still there, flashy as ever.

But now there is another reason for a stop at Rocker–the preservation of the historic frame BAP depot and the creation of the Rocker Park trail along the old railroad right-of-way. Again here in Silver Bow County we see a recreational opportunity established in conjunction with the preservation and interpretation of a key historic property. The trail was just opening when I took these photos in 2012.

Ramsay is another town along the Butte, Anaconda, and Pacific, and served as a company town for the DuPont corporation which built a short-lived munitions plant there during World War I. During the state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, historian Janet Ore was preparing a study and survey of the town resources, which was completed in 1986. The town’s historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1988. Ore noted the division between worker cottages and manager homes, and the general layout in keeping with what DuPont was doing in other states at that time. Although there has been the loss of some contributing resources in the almost 30 years since the National Register listing, Ramsay still conveys its company town feel. Below are some of the extant cottages, different variations of Bungalow style, along Laird and Palmer streets.

The superintendent’s dwelling is a two-story Four-square house, with its size, understated Colonial Revival style, and placement in the town suggesting the importance of the occupant.

A few buildings also exist from the old powder works but most were torn away decades ago. The pride of Ramsay today is its new school building, pointing toward a different future for the town in its second hundred years of existence.

In the north end, Walkerville still shows this working side of domestic architecture well.

In the north end, Walkerville still shows this working side of domestic architecture well. Here are blocks upon blocks of the unpretentious, yet homey, dwellings of those drilling out a life below the ground. And elsewhere in the city you have surviving enclaves of the

Here are blocks upon blocks of the unpretentious, yet homey, dwellings of those drilling out a life below the ground. And elsewhere in the city you have surviving enclaves of the

Some places speak to larger truths, often hidden in the landscape, of segregated spaces and segregated lives. This corner of Idaho Street (see below) was once home to the local African Methodist Episcopal church, which served a small surrounding neighborhood of black families.

Some places speak to larger truths, often hidden in the landscape, of segregated spaces and segregated lives. This corner of Idaho Street (see below) was once home to the local African Methodist Episcopal church, which served a small surrounding neighborhood of black families.

Butte–the copper city that was once the largest urban area in Montana–was a place undergoing tremendous stress at the time of state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985. The closing of the Berkeley Pit–the most scarred landscape of that time in Montana (the coal pits of Colstrip now surpass it)–shocked so many since Anaconda

Butte–the copper city that was once the largest urban area in Montana–was a place undergoing tremendous stress at the time of state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985. The closing of the Berkeley Pit–the most scarred landscape of that time in Montana (the coal pits of Colstrip now surpass it)–shocked so many since Anaconda

From here you understood that Uptown–the state’s most sophisticated urban setting–was little more than a speck within a larger landscape where people lived and toiled, scratching out lives for their families, building communities, providing raw materials to a hungry industrial world. But what seemed to me to be the vastness of Butte was actually a decidedly human response to the far greater vastness of the northern Rockies. Here was a landscape of work like few others in this nation.

From here you understood that Uptown–the state’s most sophisticated urban setting–was little more than a speck within a larger landscape where people lived and toiled, scratching out lives for their families, building communities, providing raw materials to a hungry industrial world. But what seemed to me to be the vastness of Butte was actually a decidedly human response to the far greater vastness of the northern Rockies. Here was a landscape of work like few others in this nation. There are few better places in the United States to explore the landscape of work, and how opportunity attracted all types of people from all sorts of lands to mine the copper, to house the workers, to feed the families, to provide rest and relaxation, to do all of things big and small it takes to keep a place humming 24 hours a day for decades, taking from the earth materials that made modern suburban America possible.

There are few better places in the United States to explore the landscape of work, and how opportunity attracted all types of people from all sorts of lands to mine the copper, to house the workers, to feed the families, to provide rest and relaxation, to do all of things big and small it takes to keep a place humming 24 hours a day for decades, taking from the earth materials that made modern suburban America possible. I cannot touch upon everything or everyone that define the Butte experience today but in the next several posts I want to dig deep into this landscape and discuss how this transformed place is now, for me, the most compelling spot of all in Montana.

I cannot touch upon everything or everyone that define the Butte experience today but in the next several posts I want to dig deep into this landscape and discuss how this transformed place is now, for me, the most compelling spot of all in Montana.

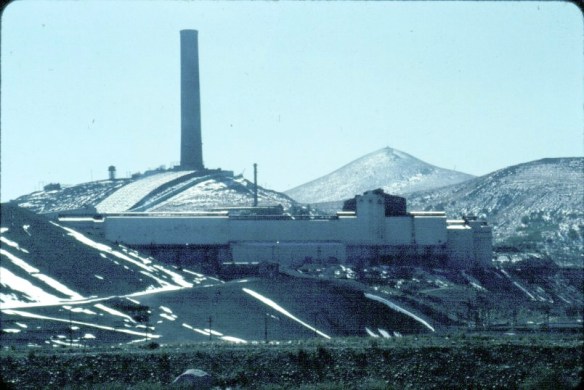

In my work across Montana in 1984-85 there was no more imposing structure than the smelter stack and works at Anaconda, in Deer Lodge County. The image above was one I used in the 20 plus listening sessions I had across the state in 1984, gathering perspectives and recommended properties for the state historic preservation plan. I used the stack because the smelter had just closed–and how this chapter in the state’s mining history could be preserved was on many minds.

In my work across Montana in 1984-85 there was no more imposing structure than the smelter stack and works at Anaconda, in Deer Lodge County. The image above was one I used in the 20 plus listening sessions I had across the state in 1984, gathering perspectives and recommended properties for the state historic preservation plan. I used the stack because the smelter had just closed–and how this chapter in the state’s mining history could be preserved was on many minds.

The Washoe Stack is one of the state’s most dominant man-made environments. For like the massive dams and reservoirs at Hungry Horse, Canyon Creek, and Fort Peck, there is the massiveness of the structure itself, and the thousands of surrounding acres impacted by the property. Unlike the lakes created by the dams of the first half of the 20th century, however, the stack left devastation in its wake, not recreation, not rebirth.

The Washoe Stack is one of the state’s most dominant man-made environments. For like the massive dams and reservoirs at Hungry Horse, Canyon Creek, and Fort Peck, there is the massiveness of the structure itself, and the thousands of surrounding acres impacted by the property. Unlike the lakes created by the dams of the first half of the 20th century, however, the stack left devastation in its wake, not recreation, not rebirth. The old gateway to the smelter introduces you to one lasting legacy of the stack–the tons of slag located along the highway leading in and out of Anaconda. The huge pile of

The old gateway to the smelter introduces you to one lasting legacy of the stack–the tons of slag located along the highway leading in and out of Anaconda. The huge pile of seems like some sort of black sand that has washed up on a beach rather the environmental spoils left by 100 years or production.

seems like some sort of black sand that has washed up on a beach rather the environmental spoils left by 100 years or production.

In the 1980s, the Atlantic Richfield Corporation, a later owner of the Washoe works, announced the stack’s closing and possible demolition. A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

In the 1980s, the Atlantic Richfield Corporation, a later owner of the Washoe works, announced the stack’s closing and possible demolition. A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

That the place remained so intact in the early 1980s was impressive to me–that it remains that way 30 years later is a testament to local stewardship, and continued good times. The interior design of Art Deco details also remain to treat the eye and tempt

That the place remained so intact in the early 1980s was impressive to me–that it remains that way 30 years later is a testament to local stewardship, and continued good times. The interior design of Art Deco details also remain to treat the eye and tempt

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks. The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

project, and the Art Moderne landmark Intermountain bus station–once so proudly featured in the Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges movie, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,” part of that decade from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s when Montana was suddenly in the lens of Hollywood.

project, and the Art Moderne landmark Intermountain bus station–once so proudly featured in the Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges movie, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,” part of that decade from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s when Montana was suddenly in the lens of Hollywood. All of these buildings and places help to give Great Falls its unique sense of self, and its sense of achievement and promise. And that is not to even mention the fun, funky stuff, such as the Polar Bears and having the

All of these buildings and places help to give Great Falls its unique sense of self, and its sense of achievement and promise. And that is not to even mention the fun, funky stuff, such as the Polar Bears and having the supper club experience of 50 years ago at Borrie’s in Black Eagle. Stepping back into time, or looking into a future where heritage stands next to the

supper club experience of 50 years ago at Borrie’s in Black Eagle. Stepping back into time, or looking into a future where heritage stands next to the atomic age, Great Falls and its environs–from Fort Benton to the northeast to Fort Shaw to the southwest–can give you that memorable heritage area experience.

atomic age, Great Falls and its environs–from Fort Benton to the northeast to Fort Shaw to the southwest–can give you that memorable heritage area experience. Successful heritage areas have chronological depth to their history, and places that are of national, if not international, significance. To begin that part of the story, let’s shift to the other side of Cascade County from Belt and explore the landscape and significance of the First Nations Buffalo Jump State Park. When I visited the site in 1984 there was not much to it but the landscape: no interpretive center existed and there were only a few markers. To give the state its due, it then only owned a portion of the site, with the first land acquisition dating to the New Deal. Listed in the National Register in 1974, the site only had opened as a state park a few years earlier, and no one seemed to know much about it or even how to get to it. But as this photograph from “A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History” shows, wow, what a view: it was totally impressive, and had a big story obviously to convey.

Successful heritage areas have chronological depth to their history, and places that are of national, if not international, significance. To begin that part of the story, let’s shift to the other side of Cascade County from Belt and explore the landscape and significance of the First Nations Buffalo Jump State Park. When I visited the site in 1984 there was not much to it but the landscape: no interpretive center existed and there were only a few markers. To give the state its due, it then only owned a portion of the site, with the first land acquisition dating to the New Deal. Listed in the National Register in 1974, the site only had opened as a state park a few years earlier, and no one seemed to know much about it or even how to get to it. But as this photograph from “A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History” shows, wow, what a view: it was totally impressive, and had a big story obviously to convey. Buffalo jumps were ways that the first nations in Montana could effectively kill large number of bisons–by planning, gathering and then stampeding a herd over a steep cliff. Native Americans used this site for hundreds, if not thousands of years. The cliff is hundreds of yards long and kill sites are throughout the property.

Buffalo jumps were ways that the first nations in Montana could effectively kill large number of bisons–by planning, gathering and then stampeding a herd over a steep cliff. Native Americans used this site for hundreds, if not thousands of years. The cliff is hundreds of yards long and kill sites are throughout the property.

State park officials, working with local residents and ranchers, have significantly enhanced the public interpretation at the park since the late 1990s. Hundreds of additional acres have been acquired, better access roads have been installed. and new interpretive features, such as these reproduction sweat lodges on the top of the cliff, have been added to the landscape to physically enhance the Native American feel to the park.

State park officials, working with local residents and ranchers, have significantly enhanced the public interpretation at the park since the late 1990s. Hundreds of additional acres have been acquired, better access roads have been installed. and new interpretive features, such as these reproduction sweat lodges on the top of the cliff, have been added to the landscape to physically enhance the Native American feel to the park. The interpretive center is a model of 21st century Native American-focus history. It provides facilities and exhibits for visitors, and encourages a longer stay and exploration of the site.

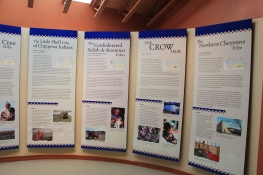

The interpretive center is a model of 21st century Native American-focus history. It provides facilities and exhibits for visitors, and encourages a longer stay and exploration of the site. Park managers understood that this site had special significance to all Native Americans thus they included capsule history displays about all Montana tribes of today along with displays that emphasize the Native American dominance of the landscape when the jump was in use.

Park managers understood that this site had special significance to all Native Americans thus they included capsule history displays about all Montana tribes of today along with displays that emphasize the Native American dominance of the landscape when the jump was in use.

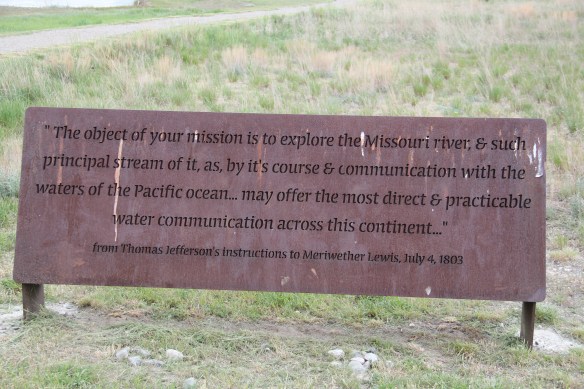

As the park was being expanded and improved into an effective heritage asset, both in its public interpretation and visitor facilities, research on the property continued. The buffalo jump is now considered the largest in the United States, and quite likely the world. In the summer of 2015, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark as one of the nationally significant archaeological and Native American properties in America. The bone deposits remain deep and rich in artifacts, still awaiting further exploration despite being mined for a brief time during World War II for phosphorus production. Indeed the entire site is one of reflection and respect for the cultural contributions made by the First Nations long before the arrival of Lewis and Clark just over 200 years ago.

As the park was being expanded and improved into an effective heritage asset, both in its public interpretation and visitor facilities, research on the property continued. The buffalo jump is now considered the largest in the United States, and quite likely the world. In the summer of 2015, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark as one of the nationally significant archaeological and Native American properties in America. The bone deposits remain deep and rich in artifacts, still awaiting further exploration despite being mined for a brief time during World War II for phosphorus production. Indeed the entire site is one of reflection and respect for the cultural contributions made by the First Nations long before the arrival of Lewis and Clark just over 200 years ago. Here is a property that today tells us how the earliest Montanans used their wits and understanding of nature and landscape to enrich their diet and to make their world, one far from that of our own, and one still difficult for those of us in the 21st century to grasp.

Here is a property that today tells us how the earliest Montanans used their wits and understanding of nature and landscape to enrich their diet and to make their world, one far from that of our own, and one still difficult for those of us in the 21st century to grasp. This buffalo jump remains a place of mystery and meaning, and when you look to the south and see the shadow of Crown Butte you glimpse into that world of the deep past in Montana,. If you look in an opposite direction you find the patterns of settlement that surround this sacred place. And that is where we go next to St. Peter’s Mission and the Sun River Valley.

This buffalo jump remains a place of mystery and meaning, and when you look to the south and see the shadow of Crown Butte you glimpse into that world of the deep past in Montana,. If you look in an opposite direction you find the patterns of settlement that surround this sacred place. And that is where we go next to St. Peter’s Mission and the Sun River Valley.