Since my initial survey of Montana historic places in 1984-1985, Montana state parks has established several small but significant historic parks. One of these, Tower Rock State Park, is viewed by hundreds of drivers daily, as it is located directly on Interstate I-15 along the Missouri River Canyon in southern Cascade County.

Native Americans traveling from their Rocky Mountain homelands into the game-rich high plains, used the rock formation, over 400 feet high, as a landmark between the two regions. The Bitterroot Salish, Lower Kootenay, and the Piegan Blackfeet are all associated with the place. For the Piegan Blackfeet it was and is a sacred place. Groups camped in the vicinity between the Rock and Missouri River.

When on July 16, 1805 Capt. Meriwether Lewis of the famous Corps of Discovery encountered the Rock on his journey west, he noted the presence of what he called an “Indian road” around the Rock. He then decided to name the place and wrote in his journal: “this rock I called the tower. it may be ascended with some difficulty nearly to its summit, and from it there is a most pleasing view of the country we are now about to leave. from it I saw this evening immence herds of buffaloe in the plains below.”

The surrounding region’s development took place in the late 19th century, accelerated by the decision of the Manitoba Road to built through the canyon a rail link connecting Great Falls, Helena and Butte. This line became known as the Montana Central Railroad.

In the early 20th century came an automobile route, U.S. Highway 91, and then the interstate highway in 1968. Interestingly, the property’s official designation as a historic site came much later. Tower Rock was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. Two years later, it became a state park of about 140 acres.

The park is day-use only but there is adequate public interpretation. There is also a maintained trail to the Rock’s base, allowing for a more direct experience with landscape and some mitigation of the noise from the highway. The importance of the place deserves a more robust treatment but perhaps more can come in the future ( and the adjacent disposal center can be moved to a more appropriate location).

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks. The late 19th century discovery and development of silver mines high in the Granite Mountains changed the course of this part of the Pintler route. The Granite Mountain mines yielded one of the biggest silver strikes in all of Montana, creating both the mountain mining town of Granite and a bit farther down on the mountain’s edge the town of Philipsburg, which by 1893 served as the seat for the new county of Granite.

The late 19th century discovery and development of silver mines high in the Granite Mountains changed the course of this part of the Pintler route. The Granite Mountain mines yielded one of the biggest silver strikes in all of Montana, creating both the mountain mining town of Granite and a bit farther down on the mountain’s edge the town of Philipsburg, which by 1893 served as the seat for the new county of Granite. The U.S. Forest Service’s rather weathered and beat-up sign marks the historic entrance to the mining town of Granite, located at over 7,000 feet in elevation above the town of Philipsburg. During the 1984-85 state historic preservation plan work Granite was the focal point. The office knew of the latest collapse of Miners Union Hall (1890) turning what had been an impressive Victorian landmark into a place with three walls and lots of rubble–it remains that way today.

The U.S. Forest Service’s rather weathered and beat-up sign marks the historic entrance to the mining town of Granite, located at over 7,000 feet in elevation above the town of Philipsburg. During the 1984-85 state historic preservation plan work Granite was the focal point. The office knew of the latest collapse of Miners Union Hall (1890) turning what had been an impressive Victorian landmark into a place with three walls and lots of rubble–it remains that way today.

Connecting the Granite road to the town of Philipsburg, today as in the past, is the site of the Bi-Metallic Mill, which is still in limited use today compared to the mining hey-day.

Connecting the Granite road to the town of Philipsburg, today as in the past, is the site of the Bi-Metallic Mill, which is still in limited use today compared to the mining hey-day.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains. Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years.

Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years. The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution

The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies. I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer

I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks. The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

Successful heritage areas have chronological depth to their history, and places that are of national, if not international, significance. To begin that part of the story, let’s shift to the other side of Cascade County from Belt and explore the landscape and significance of the First Nations Buffalo Jump State Park. When I visited the site in 1984 there was not much to it but the landscape: no interpretive center existed and there were only a few markers. To give the state its due, it then only owned a portion of the site, with the first land acquisition dating to the New Deal. Listed in the National Register in 1974, the site only had opened as a state park a few years earlier, and no one seemed to know much about it or even how to get to it. But as this photograph from “A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History” shows, wow, what a view: it was totally impressive, and had a big story obviously to convey.

Successful heritage areas have chronological depth to their history, and places that are of national, if not international, significance. To begin that part of the story, let’s shift to the other side of Cascade County from Belt and explore the landscape and significance of the First Nations Buffalo Jump State Park. When I visited the site in 1984 there was not much to it but the landscape: no interpretive center existed and there were only a few markers. To give the state its due, it then only owned a portion of the site, with the first land acquisition dating to the New Deal. Listed in the National Register in 1974, the site only had opened as a state park a few years earlier, and no one seemed to know much about it or even how to get to it. But as this photograph from “A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History” shows, wow, what a view: it was totally impressive, and had a big story obviously to convey. Buffalo jumps were ways that the first nations in Montana could effectively kill large number of bisons–by planning, gathering and then stampeding a herd over a steep cliff. Native Americans used this site for hundreds, if not thousands of years. The cliff is hundreds of yards long and kill sites are throughout the property.

Buffalo jumps were ways that the first nations in Montana could effectively kill large number of bisons–by planning, gathering and then stampeding a herd over a steep cliff. Native Americans used this site for hundreds, if not thousands of years. The cliff is hundreds of yards long and kill sites are throughout the property.

State park officials, working with local residents and ranchers, have significantly enhanced the public interpretation at the park since the late 1990s. Hundreds of additional acres have been acquired, better access roads have been installed. and new interpretive features, such as these reproduction sweat lodges on the top of the cliff, have been added to the landscape to physically enhance the Native American feel to the park.

State park officials, working with local residents and ranchers, have significantly enhanced the public interpretation at the park since the late 1990s. Hundreds of additional acres have been acquired, better access roads have been installed. and new interpretive features, such as these reproduction sweat lodges on the top of the cliff, have been added to the landscape to physically enhance the Native American feel to the park. The interpretive center is a model of 21st century Native American-focus history. It provides facilities and exhibits for visitors, and encourages a longer stay and exploration of the site.

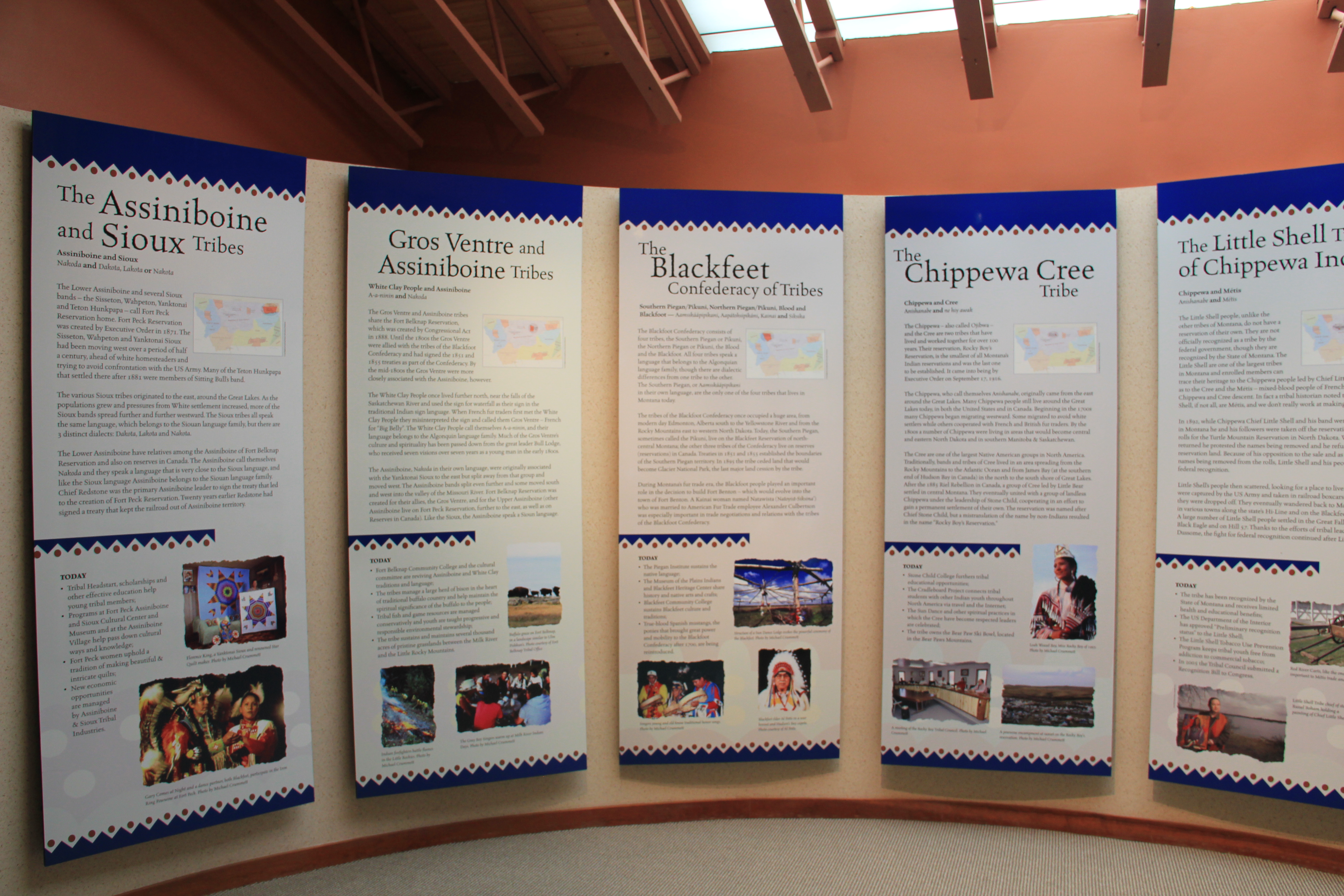

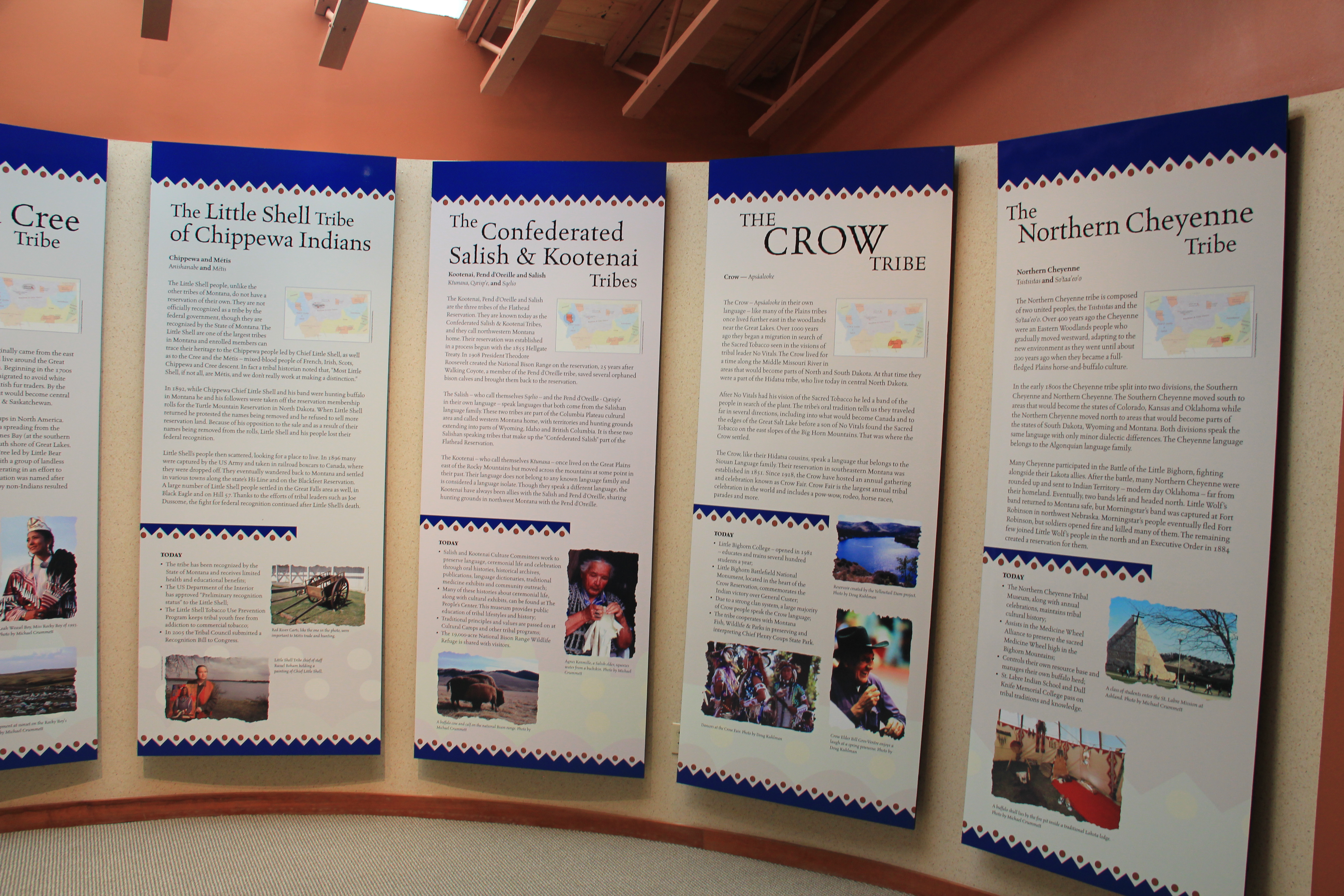

The interpretive center is a model of 21st century Native American-focus history. It provides facilities and exhibits for visitors, and encourages a longer stay and exploration of the site. Park managers understood that this site had special significance to all Native Americans thus they included capsule history displays about all Montana tribes of today along with displays that emphasize the Native American dominance of the landscape when the jump was in use.

Park managers understood that this site had special significance to all Native Americans thus they included capsule history displays about all Montana tribes of today along with displays that emphasize the Native American dominance of the landscape when the jump was in use.

As the park was being expanded and improved into an effective heritage asset, both in its public interpretation and visitor facilities, research on the property continued. The buffalo jump is now considered the largest in the United States, and quite likely the world. In the summer of 2015, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark as one of the nationally significant archaeological and Native American properties in America. The bone deposits remain deep and rich in artifacts, still awaiting further exploration despite being mined for a brief time during World War II for phosphorus production. Indeed the entire site is one of reflection and respect for the cultural contributions made by the First Nations long before the arrival of Lewis and Clark just over 200 years ago.

As the park was being expanded and improved into an effective heritage asset, both in its public interpretation and visitor facilities, research on the property continued. The buffalo jump is now considered the largest in the United States, and quite likely the world. In the summer of 2015, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark as one of the nationally significant archaeological and Native American properties in America. The bone deposits remain deep and rich in artifacts, still awaiting further exploration despite being mined for a brief time during World War II for phosphorus production. Indeed the entire site is one of reflection and respect for the cultural contributions made by the First Nations long before the arrival of Lewis and Clark just over 200 years ago. Here is a property that today tells us how the earliest Montanans used their wits and understanding of nature and landscape to enrich their diet and to make their world, one far from that of our own, and one still difficult for those of us in the 21st century to grasp.

Here is a property that today tells us how the earliest Montanans used their wits and understanding of nature and landscape to enrich their diet and to make their world, one far from that of our own, and one still difficult for those of us in the 21st century to grasp. This buffalo jump remains a place of mystery and meaning, and when you look to the south and see the shadow of Crown Butte you glimpse into that world of the deep past in Montana,. If you look in an opposite direction you find the patterns of settlement that surround this sacred place. And that is where we go next to St. Peter’s Mission and the Sun River Valley.

This buffalo jump remains a place of mystery and meaning, and when you look to the south and see the shadow of Crown Butte you glimpse into that world of the deep past in Montana,. If you look in an opposite direction you find the patterns of settlement that surround this sacred place. And that is where we go next to St. Peter’s Mission and the Sun River Valley.