It has been five years since I revisited the historic built environment of northeast Montana. My last posting took a second look at Wolf Point, the seat of Roosevelt County. I thought a perfect follow-up would be second looks at the different county seats of the region–a part of the Treasure State that I have always enjoyed visiting, and would strongly encourage you to do the same.

Grain elevators along the Glasgow railroad corridor.

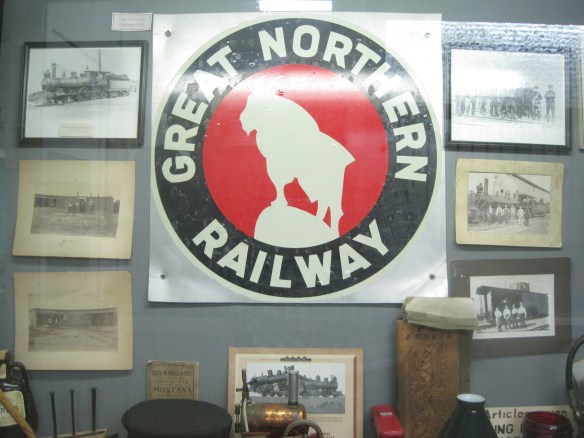

Like Wolf Point, Glasgow is another of the county seats created in the wake of the Manitoba Road/Great Northern Railway building through the state in the late 1880s. Glasgow is the seat of Valley County. The courthouse grounds include not only the modernist building above from 1973 but a WPA-constructed courthouse annex/ public building from 1939-1940 behind the courthouse.

The understated WPA classic look of this building fits into the architectural legacies of Glasgow. My first post about the town looked at its National Register buildings and the blending of classicism and modernism. Here I want to highlight other impressive properties that I left out of the original Glasgow entry. St. Michael’s Episcopal Church is an excellent late 19th century of Gothic Revival style in Montana.

The town has other architecturally distinctive commercial buildings that document its transition from late Victorian era railroad town to am early 20th century homesteading boom town.

The fact that these buildings are well-kept and in use speaks to the local commitment to stewardship and effective adaptive reuse projects. As part of Glasgow’s architectural legacy I should have said more about its Craftsman-style buildings, beyond the National

Register-listed Rundle Building. The Rundle is truly eye-catching but Glasgow also has a Mission-styled apartment row and then its historic Masonic Lodge.

I have always been impressed with the public landscapes of Glasgow, from the courthouse grounds to the city-county library (and its excellent local history collection)

and on to Valley County Fairgrounds which are located on the boundaries of town.

Another key public institution is the Valley County Pioneer Museum, which proudly emphasizes the theme of from dinosaur bones to moon walk–just see its entrance.

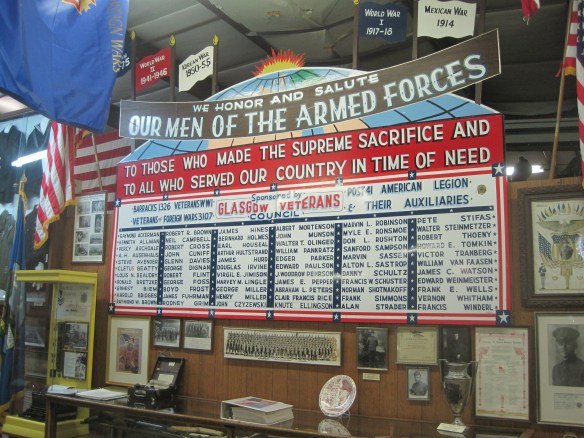

The museum was a fairly new institution when I first visited in 1984 and local leaders proudly took me through the collection as a way of emphasizing what themes and what places they wanted to be considered in the state historic preservation plan. Then I spoke with the community that evening at the museum. Not surprisingly then, the museum has ever since been a favorite place. Its has grown substantially in 35 years to include buildings and other large items on a lot adjacent to the museum collections. I have earlier discussed its collection of Thomas Moleworth furniture–a very important bit of western material culture from the previous town library. In the images below, I want to suggest its range–from the deep Native American past to the railroad era to the county’s huge veteran story and even its high school band and sports history.

A new installation, dating to the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial of 2003, is a mural depicting the Corps of Discovery along the Missouri River in Valley County. The mural is signed by artist Jesse W. Henderson, who also identifies himself as a Chippewa-Cree. The mural is huge, and to adequately convey its details I have divided my images into the different groups of people Henderson interprets in the mural.

The Henderson mural, together with the New Deal mural of the post office/courthouse discussed in my first Glasgow posting (below is a single image of that work by Forrest

Hill), are just two of the reasons to stop in Glasgow–it is one of those county seats where I discover something new every time I travel along U.S. Highway 2.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley.

One of my favorite weekend drives, when I lived in Helena over 30 years ago, was to head north, via the Flesher Pass (above) and Montana Highway 279, and hit the very different landscape of Montana Highway 200 (below) and eastern end of the Blackfoot Valley. The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

The destination was breakfast, often at Lambkin’s, a family business that, to my delight, still operates when I visited in 2015. Lambkin’s is one of those classic small town Montana eateries, great for breakfast, and not bad for a burger and pie later in the day. The town is

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse.

building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse. Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop.

Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop. But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Pony, as a gateway into the Tobacco Root Mountains, may be categorized as a ghost town in much of today’s literature about Montana, but it certainly has a lot of real people hanging around to be a ghost town. Established during the gold rush decade of the 1860s, mines here stayed in operation until World War II, and consequently, a wide range of historic buildings remain in the town today.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

Yes, Pony has a park, another of positive developments since my work in 1984-1985. The park is not only community space, but it also has various artifacts and machinery from the mining era, along with public interpretation of the district’s history and of the artifacts within the park.

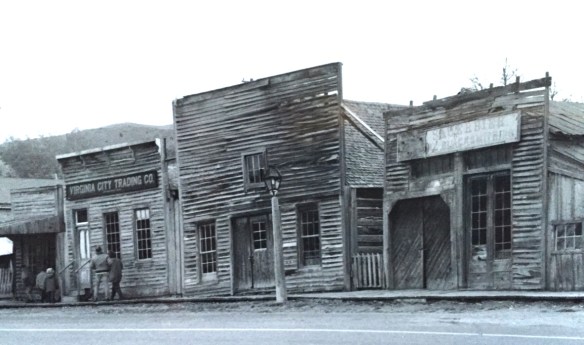

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.